Catching a Falling Knife

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

Date Published: September 23, 2022

- Category:

- US

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Following another 75-basis point hike on Wednesday, Chair Powell came to his press conference podium with a determined and singular message: “my colleagues and I are strongly committed to bringing inflation back down to our 2% goal.” Translation: we’re not done raising interest rates.

The September rate decision was accompanied by one of its quarterly forecast updates. The biggest change was in the median expectation for the policy rate. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members now expect to raise the fed funds rate a full percentage point higher relative to their view in June in order to wrestle inflation pressures back into their comfort zone.

The median “dot” or expectation reflected a fed funds rate at 4.4% by the end of this year (vs. a prior estimate at 3.4%) and 4.6% by the end of 2023 (vs. a prior estimate of 3.8%). FOMC members forecast the effective fed funds rate, so the respective upper bounds would be 4.5% and 4.75%. We should assume that they will deliver on this year’s rate hikes, given that there are only two more meetings (November 2nd and December 14th) and neither inflation, nor the labor market are likely to turn sharply enough to change their collective mind in that timeframe.

The framework laid out by Powell during the presser depicts a Fed that risks remaining literal and immediate on inflation metrics, despite the data’s backward-looking nature. This makes it entirely possible that the policy rate could reach 4.75% within the first quarter of 2023, with a risk of pressing even higher that year. Should this occur, a formal recession would likely become our baseline view, and this could also become true for many other forecasters. One comfort we draw from the “dot plot” is that it represents the views of 19 members, while only 12 have voting rights. So it’s always possible that the “dots” of the voting members represent a more tempered position on the speed of adjustment and the final resting place for the policy rate. This could be revealed within their public speeches in the months ahead.

In a 4% policy world, we had a baseline forecast reflecting economic stagnation for the next two years, putting us below the consensus. This corresponded with several quarters of job losses and a steady rise in the unemployment rate to 5.1% through 2024. A 1.5 percentage point swing in the unemployment rate would hew close to a 2001-type experience – where the recession call is often still debated. A policy rate that moves into even more restrictive territory would tip the scales deeper into formal recession dynamics.

| Period | Annualized PCE Inflation (%) | ||

| 3 Month | 6 Month | 12 Month | |

| 2022 - Q1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| 2022 - Q2 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| 2022 - Q3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.7 |

| 2022 - Q4 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| 2023 - Q1 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.9 |

| 2023 - Q2 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| 2023 - Q3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 3.0 |

| 2023 - Q4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

There’s a lot to unpack here, so let’s start with why we are concerned that the Fed could overshoot on the policy rate in what’s already going to be the fastest adjustment in over 40 years.

First, during the press conference, Powell cited quit rates and job vacancies as areas to watch to gauge an easing in labor market tightness, as well as the usual unemployment rate. The starting point on quits and vacancies is strong and better than its respective historical averages. For job vacancies, it’s in the extreme with nearly a two-to-one ratio on vacancies to available labor. By extension, it would take some time to erode these metrics to a point where it would offer compelling evidence of labor market slack.

The second item that caught my ear was Powell citing that the trailing three-month, six-month and 12-month core inflation rates were all holding well above 4% and “tightly fitted” to each other. By that I’m referring to the three-month growth rate showing little deviation from the six- and 12-month rates. This needs to be a “first condition” to show that cooling dynamics have taken hold in the near term. However, when we map these metrics with our inflation forecast (see table on page 1), a meaningful deviation does not present itself until the first quarter of 2023. Why? Because it’s a backward-looking indicator that will take time to capture current dynamics. We are likely still a few months away from past rate hikes making their presence known in the data.

For instance, the Manheim used vehicle price index (UVPI) is based on dealer auction prices and can show big differences with the used vehicle price component in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) when comparing similar periods. The UVPI has fallen roughly 10% off its high in January-February, while the used vehicle component of CPI is only down 1.5%. There’s roughly a one to two-month lag from changes in the Manheim to changes in CPI. That doesn’t change the fact that both indices remain elevated, with dealers likely keeping prices higher to maintain wider margins. However, there will be a natural downward pull on these metrics as time passes.

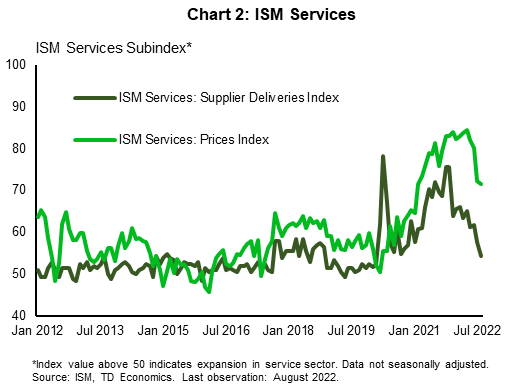

A chorus of soft indicators are also showing a bend in the curve. These include the ISM indicators for manufacturing and services (Charts 1 and 2), the New York Fed’s consumer-based inflation expectations survey and the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) survey in August also showed another significant pull-back in the share of firms planning to raise prices.

Inventories are more bloated than they once were, and this is a precursor to future price discounting. The inventory-to-sales ratios across department stores, home furnishing, electronics and appliance and building materials stores are all sitting above their respective pre-pandemic levels.

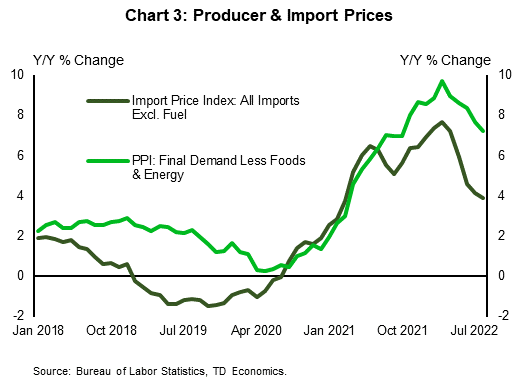

And finally, the pipeline of input-price pressures has turned. Producer and import prices have crested and are now easing noticeably, even when energy components are removed (Chart 3).

The rapid rate hiking cycle has only just begun to bite the economy and behaviors, with 225 basis points in hikes having occurred in just the past three months. Given the transmission lags of policy onto demand, and that lag into end-user prices, the Fed’s preferred inflation metric (core PCE) is unlikely to offer “convincing” evidence of a sustained downshift until 2023. The Fed’s current approach to monetary policy suggests the policy rate rate could push to 4.75% by the first quarter of 2023.

So, why does a recession look probable in that environment?

- The FOMC’s median economic forecast is too rosy and contains too many logic gaps. Powell noted the necessity of realigning demand with supply. In fact, to take heat off inflation, demand growth needs to underperform for a significant amount of time, assuming there’s not a meaningful counter-response on the supply side. The Fed’s median GDP growth profile is 1.2% (Q4/Q4) in 2023, only marginally below their estimate of potential GDP (1.8%). We don’t believe that would create the dynamics to sufficiently suppress demand to allow inflation to run off. With our GDP forecast of only 0.7% (Q4/Q4), it would still be a slow grind down on inflation, which is why our 2024 GDP profile also holds below trend.

- The same logic holds on the unemployment rate. In the Fed forecast, it comes to miraculously rest and hold at 4.4%, just a sliver above their estimate of NAIRU.

Basically, it’s difficult to reconcile their economic profile with the level and speed of adjustment on interest rates. Their GDP profile would likely maintain too much demand misalignment, particularly since companies typically adjust investment and the supply side downwards as their own growth expectations become more tempered.

Putting the pieces together, if the Fed follows through with a more heavy-handed rate profile, it will result in a downgrade to our already weak baseline forecast. By extension, it’s reasonable to assume that the back half of 2023 would usher in rate cuts, despite the FOMC “dot plot” not entertaining that notion until 2024. A harder landing on the economy would hasten the deceleration in inflation and open the door for some policy reversal.

Even if the Fed were to cut 100 basis points at year-end to bring the policy rate back to a 3.50% to 3.75% range, this would still leave interest rates in restrictive territory. Although Powell came out swinging at the press conference with a very direct and almost stern tone on opening statements, he has little choice but to talk tough to keep inflation expectations anchored. If the economy deteriorates at a swifter rate – as we expect – then the Fed would likely shift its tone and views.

At the end of the day, it’s important to remind ourselves that this is a central bank that has backed itself into the corner – the hazard of being too far behind the inflation curve. Its policy reaction function is backward looking, rather than forward looking, as with past cycles. This raises the risk of a policy overshoot. In fact, by having trained Wall Street and Main Street to emphasize the current inflation statistics, the Fed may have little choice but to overshoot in the near term relative to what the economic fundamentals will warrant if an eye is cast to the future. To not do so could risk unhinging inflation expectations.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: