The Non-Starter Playbook of the Mar-a-Lago Accord

Maria Solovieva, CFA, Economist | 416-380-1195

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: May 1, 2025

- Category:

- US

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- The Mar-a-Lago Accord is a proposed blueprint to recreate the 1985 Plaza Accord, designed to correct the U.S. trade deficit through deliberate dollar weakening.

- While theoretical, the Mar-a-Lago Accord outlines several unconventional instruments to make the dollar less attractive to reserve holders, which in practice would be highly disruptive even if implemented gradually as prescribed.

- We expect this part of the blueprint to remain on the shelf. However, if elements of the Mar-a-Lago playbook are initiated, it could place further downside pressure on the dollar, beyond what current fundamentals imply.

The first 100 days of the new administration have flirted with, or outright introduced, many unconventional economic policies. These range from a historic global jump in tariffs, to notions of returning to the gold standard, to even a reprised version of the Plaza Accords monikered the Mar-a-Lago Accord. The latter proposes a fundamental shift in global financial markets and international trade, attempting to retrofit economic theory onto Trump’s tariff-first trade agenda. At its core is the flawed premise that U.S. trade deficits are driven by foreign demand for reserve assets – an idea with little validation in real-world capital flow dynamics. Markets are already responding to the U.S. withdrawal from international economic engagement and trade integration. Layered on top of this confidence shift, the framework would risk further undermining trust in U.S. risk-free assets. Even if unofficial, these proposals carry market consequences. If executed, especially through measures like selective default, they could trigger a credibility shock that severely damages the U.S.’s standing as a financial safe haven.

What is the Mar-a-Lago Accord?

The idea drew inspiration from the 1985 Plaza Accord, with the term referencing both a historical analogy and a symbolic location: Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club, which he acquired the same year that the Plaza Accord was signed.

This term was coined by the now Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors Stephen Miran in an essay titled “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” that he wrote before he was part of the Trump administration. While it does not serve as an official policy blueprint, it likely functions as a strategic framework or guiding document for how to shape the global trade and financial order.

Miran’s central thesis is that persistent U.S. trade imbalances are rooted in the structural overvaluation of the U.S. dollar, driven by global demand for reserve assets. The remedy lies in a downward adjustment of the dollar to a “fairer” value, which he argues “can be redressed by tariffs”. He outlines multilateral and unilateral strategies for achieving this adjustment, while emphasizing that any intervention must be implemented gradually to avoid triggering destabilizing outflows from the U.S. Treasury market.

Why the comparison to the Plaza Accord of 1985?

The Plaza Accord was a multilateral agreement between the G5 nations – the U.S., Japan, West Germany, France, and the U.K – that also intended to correct the U.S. trade deficit. Its goal was to weaken the USD through coordinated currency intervention and fiscal adjustment (primarily by non-U.S. participants) to rebalance global trade flows.

However, several key conditions that made the Plaza Accord possible in 1985 no longer hold today. First, most central banks in developed countries no longer intervene in the currency markets (unless there is a financial stability concern). In addition, China is now a dominant global trade power and America’s primary trade rival. It is unlikely to voluntarily allow the yuan to appreciate vis-a-vis USD to achieve U.S. policy objectives. If anything, China is more likely to let its currency depreciate to support domestic growth.

While the Plaza Accord succeeded in weakening the dollar in the short term, it failed to deliver lasting improvements in trade balances, largely because the underlying dynamic of low private savings and high government borrowing in the U.S. remained unaddressed.

What is the state of the U.S. trade deficit?

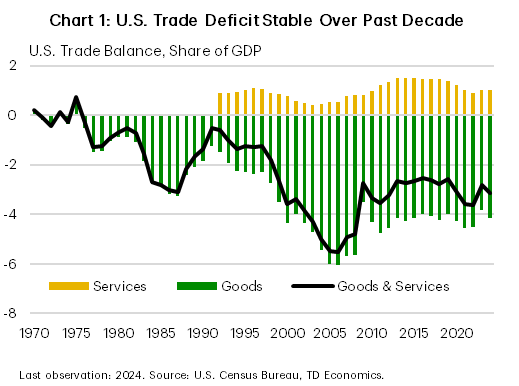

The U.S. has run a goods trade deficit with the world for nearly fifty years. As a share of GDP, the goods trade deficit capped out at 6.1% in 2006, but has remained stable at roughly 4% over the past 15 years (Chart 1). At the same time, the U.S. has maintained a persistent services trade surplus with the world equal to roughly 1% of GDP over the past 30 years. This puts the cumulative trade deficit with the world equal to roughly 3% of GDP.

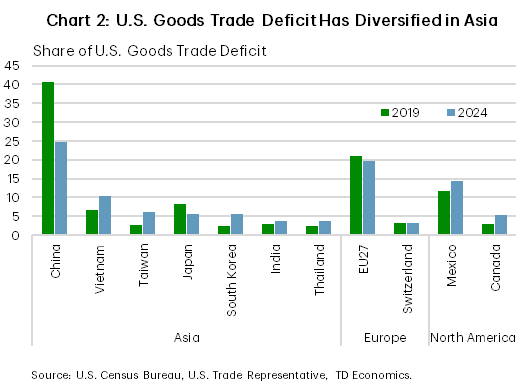

The composition of the U.S. trade deficit in goods is diverse across countries and has changed notably over the past five years. In 2019, nearly half of the U.S. trade deficit in goods was concentrated in China (Chart 2). Fast forward to today, and we can see that China’s share has fallen to a quarter, with other Asian nations and Mexico largely picking up the slack. In 2024, China, Mexico, and Vietnam accounted for roughly half the U.S. goods trade deficit.

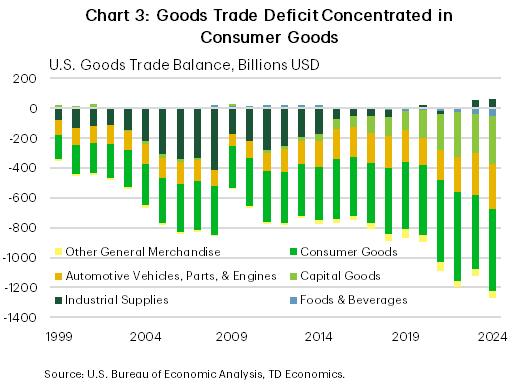

Despite being the second largest exporter of goods in the world behind China, the U.S. still consumes more than it produces across most product categories (Chart 3). The only exception is industrial supplies & materials, which runs a modest surplus owing to the country’s sizeable exports of energy products. Consumer goods encompass most of the goods trade deficit (70%), which is primarily driven by electronics, automotive vehicles, and pharmaceutical products. Generally speaking, Asia accounts for the lion’s share of the electronics deficit, Europe the pharmaceutical product deficit, while the automotive deficit is broad-based with a moderate concentration in Mexico.

Taken altogether, these statistics provide partial clarity on the administration’s rationale for some of its tariffs, given its broadly defined goal of “trade reciprocity.” The U.S. currently has product specific tariffs of 25% in effect on automotives, with similar tariffs expected to be levied on pharmaceutical products later this year. Interestingly, despite the sizeable share of the U.S. trade deficit that is accounted for by consumer electronics, many of these products were exempted from the global reciprocal tariffs put into effect in early April. However, if they are sourced from China, they would still be subject to the February/March tariffs of 20% in addition to the Section 301 tariffs implemented during President Trump’s first term.

The administration’s overall trade policy goals appear to conflict. The stated objectives of reshored manufacturing capacity, tariff revenues, and negotiated trade deals contradict each other to varying degrees. If imported goods are replaced by domestic production through reshoring then it will decrease imports and by extension, tariff revenues. At the same time, if tariffs are negotiated to lower levels, it would decrease the incentive to reshore production and lower tariff revenues. These objectives can coexist but will be less effective if pursued jointly. Grander ambitions related to reorganization of the international order of trade and finance have also been considered, but this becomes exponentially more complex.

A Weak Dollar Policy is A Risky Proposition

Consistent with the broader logic of the Trump trade policy, the world has an insatiable and price-insensitive appetite for dollar assets, which has kept the dollar too high, making American exports uncompetitive and sustaining a long-standing trade deficit.

This argument challenges a conventional narrative. Rather than seeing rising U.S. debt as a function of domestic overspending, Miran argues that the U.S. government is effectively forced to run a deficit and issue debt to meet global demand for safe dollar assets. In reality, U.S. fiscal policy has been heavily shaped by domestic choices, including tax cuts in the 1980’s, 2000’s, and 2010’s that prevented federal revenues from keeping pace with the structurally higher outlays, driven by aging demographics and national defense spending. Economic shocks such as the Global Financial Crisis and COVID-19 further inflated federal debt levels. So, the idea that America imports too much simply because it must export reserve assets and “facilitate global growth” is akin to saying the wind blows because trees are swaying.

Beyond the demand for reserves, there are multiple other channels that drive global demand for U.S. assets. Many developing countries peg their currencies to the dollar and must accumulate U.S. dollar-denominated assets to maintain their pegs. A significant share of global trade is invoiced in dollars, prompting exporters around the world to hold dollar reserves for prudent cash and liquidity management. In addition, U.S. multinational companies establishing subsidiaries abroad generate cross-border flows that are booked as liabilities on the U.S. international investment position, further influencing the capital account.

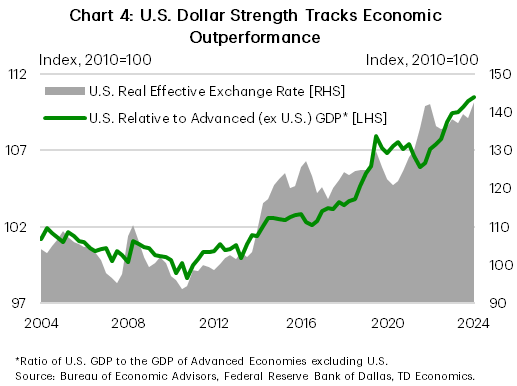

Moreover, U.S. Treasuries are not the only assets acquired by foreign investors. In fact, Treasuries accounted for only about a quarter of total U.S. external liabilities as of 2024, with the remainder comprising direct investment, equities, investment fund shares, and financial derivatives. Clearly, central bank reserve accumulation is just one part of a much broader and more complex capital flow dynamic influencing the dollar’s strength. Beyond external demand, U.S. borrowing capacity is also underpinned by strong domestic fundamentals – exceptional labor productivity, innovative capacity, and deep, flexible capital markets. The U.S. has consistently outpaced advanced-economy peers in technology adoption, business formation and economic resilience (Chart 4). These strengths supported the real appreciation of the dollar. Yet as growth slows and policy uncertainty rises, the narrative of American exceptionalism is beginning to fray. Push this one step further, and the credibility of the U.S. government and its currency, carefully built over decades, could be seriously questioned.

Mar-a-Lago: A Hard Pill for Markets to Swallow

Against this backdrop, it is especially strange that Miran proposes that the U.S. should take deliberate steps to make the dollar less attractive to reserve holders. At the same time, he acknowledges a key political contradiction: President Trump has praised the dollar’s reserve status and threatened countries that seek alternatives. To navigate this tension, Miran suggests two broad approaches.

The first is a modern-day Plaza Accord-style multilateral agreement to coordinate a controlled dollar depreciation. However, such an agreement appears highly unlikely today. Central banks no longer engage in routine currency interventions, and major reserve holders like China and Middle East Gulf states are unlikely to cooperate. Private investors, over whom Trump has no leverage, now hold a significant share of dollar assets. One variant of this approach is to tie defense guarantees to reserve holdings, requiring allies to hold century bonds (100-year Treasuries) as a condition of continued U.S. security support. Yet, Miran concedes that with most U.S. dollar holdings concentrated in less-friendly nations and private markets, the feasibility of such plan is extremely limited.

Given the limits of diplomacy, Miran then outlines a unilateral strategy. Using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the administration could impose a “user fee” on foreign official holders of Treasuries by withholding a portion of their interest payments, effectively taxing them. In contractual terms, this would amount to a selective debt default, though Miran frames it as a necessary adjustment. His key argument is that if foreign reserve buyers are truly price-insensitive, the demand for Treasuries may not fall sharply, but the U.S. could still save on interest costs. To reduce market disruption, he advocates for a gradual approach, starting with a small fee, targeting adversarial nations first while also seeking voluntary Fed cooperation to maintain market liquidity.

Introducing a default-like event is deeply concerning as it would inject explicit credit risk into what is supposed to be a “risk-free” asset market that underpins the foundation of the global financial system. Treasuries are priced based on the assumption of full and unconditional payment and tampering with that assumption would immediately reprice U.S. sovereign risk. As recent bond market volatility triggered by the announcement of reciprocal tariffs already illustrated, even the threat of such measures could seriously shake confidence. Investors would react swiftly by demanding higher yields, weakening the dollar further. A cautionary example is the U.K. under Prime Minister Liz Truss, where poorly communicated fiscal policies triggered a yield spike in Gilt yields, damaged investor confidence, and forced an emergency intervention at the Bank of England. The U.S. faces an even greater risk, given its central role in global finance. That line hasn’t been crossed yet, but undermining Treasuries would shake the foundation to its core.

Bottom Line

The Mar-a-Lago Accord is a blueprint to recreate the Plaza- Accord-style intervention of decades prior, designed to correct the U.S. trade deficit through deliberate dollar weakening. The current composition of the U.S. trade deficit, particularly the concentration with China, sheds light on the administration’s rationale for tariffs. Yet while tariffs may adjust trade flows at the margin, the strong U.S. dollar continues to make American exports less competitive and poses a major obstacle to reshoring manufacturing and rebalancing trade.

Miran’s blueprint for a weak dollar policy attempt to retrofit economic theory onto Trump’s tariff-first agenda. It rests on the flawed premise that U.S. trade deficits exist to accommodate global demand for reserve assets – an idea with little validation in real-world capital flow dynamics. Markets are already responding to the U.S. withdrawal from international economic engagement and trade integration. Layered on top of this confidence shift, the framework would risk further undermining trust in U.S. risk-free assets.

Against this backdrop, we don’t expect this part of the blueprint to be pursued. Particularly since underlying fundamentals point to further dollar weakness of an additional 3-5%, depending on how quickly the Fed reduces its policy rate. However, if elements of the Mar-a-Lago playbook are initiated, further downside pressure on the dollar could form, beyond what underlying fundamentals would suggest today. Given President Trump’s preference for aggressive action and the market’s predisposition towards risk aversion, any renewed pressure on the dollar could unfold much faster and more disorderly than markets might anticipate.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: