The Federal Reserve: A Bird on the Wire

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: January 25, 2024

- Category:

- Us

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Strong economic growth has enabled the Fed to delay cutting interest rates to ensure inflation dynamics don’t pop back up.

- Geopolitical events and buoyant consumer spending create a risk that inflation could pick up again.

- The first rate cut and the pace of cuts thereafter will likely be slower than current market pricing implies.

The late-great Leonard Cohen once said, the older I get, the surer I am that I’m not running the show. Could this be how Fed Chair Powell feels with markets eagerly anticipating rate cuts? So far, not a single voting Fed member has tipped their hand that a rate cut is imminent. In fact, it’s been the exact opposite, with a chorus of speakers indicating a preference towards patience.

Yet financial markets keep batting around the odds of that first interest rate cut to be somewhere between the March and May FOMC meetings. We believe this is optimistic and place the timing closer to the June-July period. Market participants are exhibiting confirmation bias, even when the economic data reveal an economy less sensitive to interest rates relative to the past.

Just look at what transpired following the non-farm payrolls report in early January. At 8:30 am, the data surprised to the upside, causing the yield curve to jump higher by 7 basis points. But at 10am, the release of the ISM services report printed below market expectations, prompting market sentiment to violently swing in the other direction. The yield curve moved down by 15 basis points. The market over-weighted the signal from the ISM services report, despite it being a sentiment indicator that continued to show an economy in expansion territory and arguably was the less significant of the two reports that morning. Frankly, on most months, the ISM services index only gets a passing glance by market participants.

Last week, an incredibly impressive retail sales report revealed a U.S. consumer that will not go gently into that good night. In fact, the data prompted an upward revision to consumer spending estimates in the fourth quarter — marking yet another quarter of an above-trend pace. But even this failed to pull markets fully away from a rate-cut expectation in March, which held its grip at roughly 50% odds.

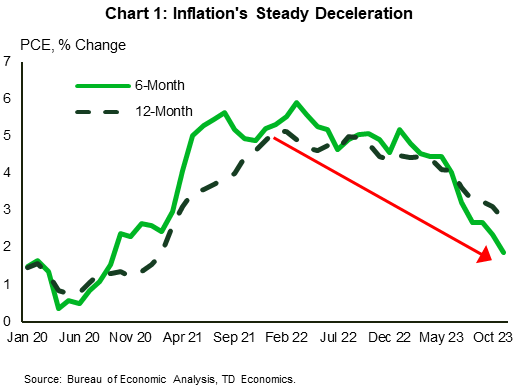

Cooling inflation reports have reinforced this market psychology despite annual inflation remaining a fair distance from the desired target (Chart 1). After all, the Fed has indicated that they don’t need inflation to be at the 2% target before cutting interest rates, they just need to be firmly convinced it will achieve that outcome.

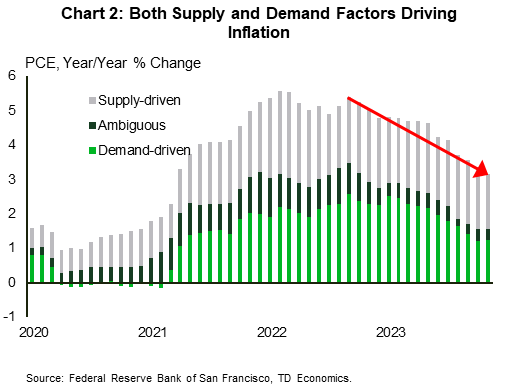

But what if the markets are looking at this through the wrong lens? There has been virtually no “economic sacrifice “ with the policy rate at 5.50%, so far. In fact, the U.S. economy expanded at a faster pace in 2023 than the year prior. The dynamics of excess savings, fiscal stimulus, strong wage growth and sturdy labor demand have created a fortress of resilience, even with the economic impulse from each of these metrics lessening with the passage of time. Doesn’t this argue that the Federal Reserve can afford to wait a bit longer before cutting interest rates to mitigate the risk of stoking demand-side inflation? The Fed’s own analysis has demonstrated that demand-driven inflationary pressures are still elevated relative to pre-pandemic, and the supply side has yet to fully normalize. Now add in recent geopolitical risks that have doubled freight shipping costs in 2024, and this isn’t an economy that screams urgency on cutting interest rates.

Inflation is Easing for all the Right Reasons

When the Fed brought its policy rate to a 22-year high in July 2023, the narrative was: the higher it goes, the quicker it will fall. Historically this has been true. During the 1980s, the time between the last rate hike and the first cut was just a month. By comparison, following the Fed’s slow rate hike cycle of the early 2000s, it took 15 months before they felt confident in reversing the path. Looking at the various interest rate cycles, the median amount of time between hike and cut was about eight months. That timing always depends on how quickly the economy deteriorates. In the current cycle, it has been six months since the last Fed hike and the economy has barely hit a speed bump.

The Fed will cut rates when the risk to economic growth outweighs the inflation impulse risk. This typically is accompanied by a weak (not merely softening) job market, alongside weakening consumer spending and below trend GDP growth. This condition tends to be mirrored within financial market sentiment via worsening equity markets. None of this is happening yet. GDP grew at 3.3% in the fourth quarter after hitting 4.9% in the third quarter of 2023. Job demand is slowing but remains about one-and-a-half times above trend.

Against this backdrop, there’s been lots of debate over the drivers behind cooling inflation. Research from the San Francisco Federal Reserve has broken the issue into the two camps of supply versus demand influences within the Fed’s preferred core PCE inflation metric. It shows that less than half of the deceleration in core inflation over the last 16 months has been driven by an easing in supply-side factors, such as loosening shipping costs and decreased risk premiums from geopolitical conflicts (Chart 2). This implies that if supply-driven inflation continues to ease to more normal levels, then core PCE will be back to the Fed’s target without requiring demand driven inflation to decelerate. In other words, not much “growth sacrifice” within the economy is required. However, the supply side risks have recently come back to the forefront with shipping traffic disruptions and risk premiums rising in the Red Sea. While it’s nowhere near the levels during the pandemic, it could disrupt the speed or scale of the downward momentum in U.S. inflation stemming from the durable goods -side of consumer purchases. This has been trending in deflation territory for six months and is a key disinflationary force on the broader metric, compared to the service-side of the economy, which is running at more than 4% year-on-year (y/y).

Good News on Inflation Means More Fed Patience

If the current level of the Fed’s policy rate isn’t forcing economic growth below trend, then cutting interest rates too soon could cause a resurgence in inflation. This would be reminiscent of what happened in the 1970s and 1980s twin peak inflation episodes. In 1974, inflation reached a high of 12.3% y/y, prompting the Fed to raise its policy rate to 13.3%. This worked to ease inflationary pressures , which fell to a low of 4.9% y/y two years later. Under a bit of false confidence that inflation would continue on the downward path, the Federal Reserve cut the policy rate by over nine percentage points. But the job wasn’t done. Inflation re-emerged, reaching an all-time high of 14.8% y/y. The Fed was then forced to go even further to break the back of inflation, resulting in a policy rate peak of 22% in 1980. The economy was subsequently in recession for most of the 1980 to 1982 period. This lesson is still fresh in the minds of Fed members, which is why they continue to reinforce the importance of having a high degree of confidence that inflation will not just return to the 2% target, but will be sustained there for years to come.

Chair Powell couldn’t have said it more clearly: “We still have a ways to go. No one is declaring victory.” The procession of Fed members since have reinforced Powell’s position. Most have conveyed the view that they are happy with the recent progress of inflation, but there is risk that the demand side of the economy reinvigorates price pressures. This should keep the Fed leaning against markets earlier timing for interest rate cuts.

Luckily the Fed isn’t alone. Other major central banks are pushing expectations for cuts into the summer. ECB President Lagarde said she is waiting for April and May data to confirm the staying power of lower inflation. Meanwhile, the Bank of England has stood firm, stating its intention to keep rates at current levels for “an extended period”.

Bottom Line

Investors and the Fed need to focus on the hard data. If economic growth starts to stall, as it has in other developed economies around the world, the Fed could develop the confidence that a build-up of economic slack would do the remaining heavy lifting to anchor prices and expectations. With domestic demand holding firm and geopolitical risks heating back up, the Fed has time on its side to observe the evolution of the economy and be convinced of inflation’s trajectory.

This means that it’s not yet secure when that first rate cut will occur, as well as the cadence that the central bank will deem appropriate. There are many paths the Fed could take, as long as the economy is still expanding. Markets currently have more than 125 basis points in cuts over 2024, but this looks too aggressive. And, the Fed could even choose to cut rates at an every other meeting interval as they probe for the right balance between supply and demand forces. There’s nothing in the rule book that they need to have a measured response, as we saw during the rate hike cycle. Should cuts either be delayed and/or the pace uneven, there could be a quick repricing in bond markets.

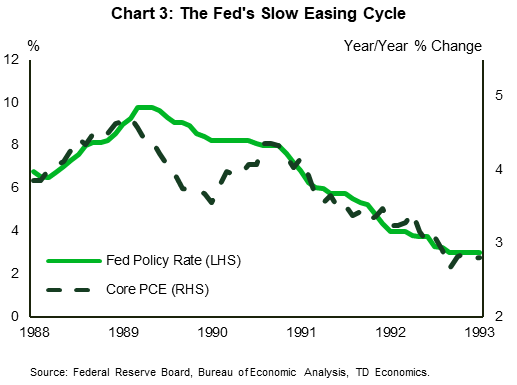

This appears to be what the Fed is already signaling within their famous “dot plot”. The central bank views 2.5% as the final resting state for its policy anchor. But importantly, it expects it will take more than three years to get there. That would be reminiscent of the 1989 to 1992 cycle, where the Fed took several pauses. Granted, the Fed had further to go, with a policy rate jump-off of nearly 10% in 1989. But that cycle also reflected an inflation environment with many stops-and-starts (Chart 3).

The bottom line is that the data does not convey a sense of urgency, nor the messaging from the Federal Reserve. For as long as the economy remains strong, the Fed will have optionality on when it decides to cut rates.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: