U.S. Government Shutdown Breakdown

James Marple, Associate Vice President | 416-982-2557

Rannella Billy-Ochieng’, Senior Economist | 416-350-0017

Brett Saldarelli, Economist | 416-542-0072

Date Published: September 25, 2023

- Category:

- US

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- The current budget impasse in Congress threatens to shut down non-essential government departments and agencies without independent funding at midnight on September 30th.

- This isn’t new territory. Prior shutdowns have led to limited negative impacts on economic growth despite being disruptive to agency functioning, government contractors and social services, thereby imposing costs on communities across the country.

- The financial market reaction to past government shutdowns has been benign with the S&P 500 often recovering losses before the government reopens.

History’s experience is only a guide. This one would occur at a time when economic and financial risks already abound with interest rates at a 22-year high.

All eyes are on Capitol Hill where the latest spending fight in Congress is approaching another critical deadline. Lawmakers have until the end of the week to pass 12 annual appropriation bills (or an omnibus bill) needed to fund roughly 25% of the government before the end of the fiscal year. This is unlikely to occur. As existing appropriations expire, unfunded portions of the government will shut down.

Despite capturing headlines, government shutdowns have historically been short lived and carry minimal impact on the economy and financial markets. Still, heightened political polarization raises the chance that this could be a long shutdown, and the disruption would come at a time when late-cycle dynamics and other event risks (a potential UAW strike, student loan payment resumption) are already adding to the strains on the economy. Finally, with government statistical agencies shut down, it could leave the Federal Reserve operating without key economic data as it considers its next policy move.

A Made in America Problem

Shutdown risk is nothing new. Congress typically struggles to pass annual spending bills before the September 30th deadline. When confronted with eminent funding disruptions, lawmakers can use short-term spending bills (called continuing resolutions) to bridge the gap. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, there have been 47 continuing resolutions over the fiscal period 2010-2022, that have kept the government funded well past the end of the fiscal year.

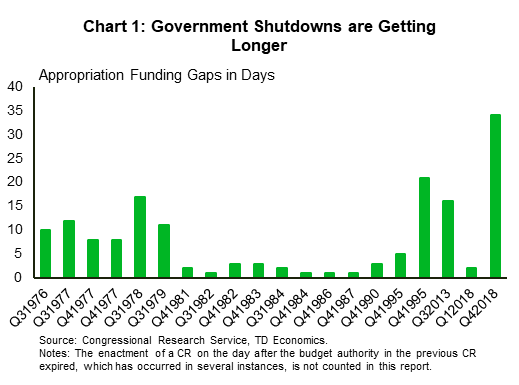

When the can cannot be kicked down the road, un-funded portions of the government are shuttered. Since the 1970s, there have been 20 such instances.1 Most have been short, and shutdowns typically last for a period of four days. However, over the last three decades, the length of these funding gaps has been growing longer. The most recent partial government shutdown ran from December 22nd, 2018 to January 25th, 2019 – making it the longest on record at 34 days (Chart 1).

Government shutdowns, however, are not all created equal. The amount of the government impacted depends on how many of the 12 standard appropriate bills are passed, or how much of the government is funded through continuing resolutions. In 2018, Congress passed a “minibus” bill that combined five of the 12 annual appropriation bills funded close to 80% of the discretionary funding at risk. In 2013, by contrast, not a single one of the 12 appropriation bills was passed, resulting in a total shutdown of non-essential government services.

At present, with the political parties still quite far apart, 2013 is the more likely episode to be repeated in scope, although the length of period remains a greater mystery. Even if it is short lived, it will likely prove more damaging than the very partial shutdown that took place in 2018.

Federal Workers Suffer the Brunt of the Impact

Congress’s inability to come to a timely resolution will have the biggest impact on federal workers. Federal workers who are deemed essential will still have to report to work but will not be paid, while those deemed non-essential are furloughed (sent home without pay).

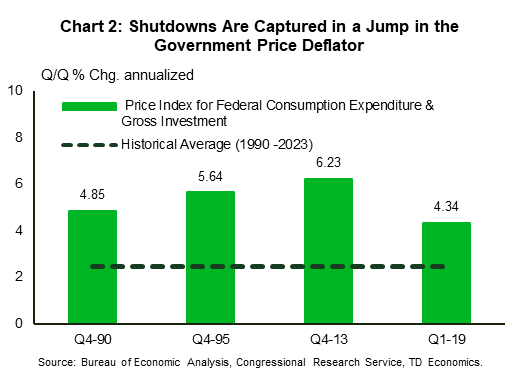

The good news is that even furloughed workers will eventually be paid for their forced vacation time. A bill passed in 2019 guaranteed retroactive backpay for all government employees impacted by funding gaps.2 As a result, the shutdown will end up costing the government more in the end – it still has to pay workers despite services not rendered. In past shutdowns in which workers were paid in full for time missed, this showed up in a jump in the price index for government spending in GDP, as nominal spending remained the same in the quarter, but real activity fell (Chart 2).

Still, not all workers are likely to be kept whole. Others impacted by the shutdown are private businesses that have contracts with the federal government. During the shut-down period, no new contracts are signed and any contractor that has work with non-essential government personnel are unable to do their jobs. In some cases, the government will provide relief to contractors negatively impacted by the shutdown, once again adding to the cost to the public purse.

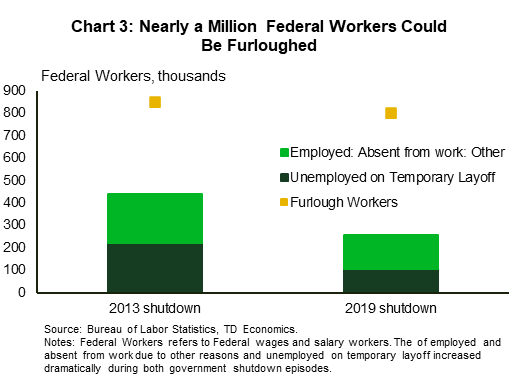

The impact on the overall job market is much less significant. During the past two major government shutdowns in 2013 and the short-lived one of early 2018, roughly 800k workers were furloughed, or 35% of the civilian non-post office federal workforce (Chart 3).3 In the longer-lived 2013 experience, most of the 350k civilian defense employees were called back to work (without pay) within a week. Given the size of the federal government is larger today than those periods, a full shutdown could result in 900k workers being furloughed this time around. This could show up in the employment report in the month in which it occurs, but since these workers will eventually be paid, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will still count them as employed for the purposes of the payroll survey. It will, however, count them as unemployed (on temporary layoff) in the household survey.4

The Economic Costs of the Shutdown

Given the likelihood of a full government shutdown, the best historical examples are 1995 and 2013. Studies of these two incidences, including knock on effects to the private sector, suggest that every week could cut as much as 0.2 percentage points from annualized real GDP growth (in the quarter in which it occurs). However, most of this activity will likely be recouped once the shutdown has ended. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the permanent impact of the 2018 episode was about a $3 billion reduction to GDP, representing 0.02% of economic activity.5

There’s no way to know how long a shutdown may last. However, one potential incentive for agreement is that the paychecks to uniformed officers are due on October 13th. But Congress will have to also be mindful of the implication of putting in place a stop gap solution as a quick fix. In order to resolve the debt ceiling impasse, the recent Fiscal Responsibility Act included a clause stipulated that should there be a continuing resolution in place on January 1st, 2024, it would result in steep cuts to defense spending. Neither party would likely want to bear this responsibility.

Financial Markets Tend to Discount Funding Disruptions

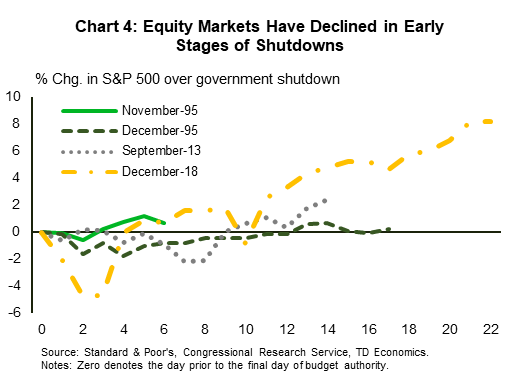

From a financial markets perspective, it is difficult to disentangle a direct effect of shutdowns given the myriad of forces at play on a daily basis, but equity indexes do appear to respond negatively to the news initially, subsequently recovering even before a resolution is apparent. Looking at recent government shutdowns, the S&P 500 declined at the onset, but surpassed its pre-shutdown levels by the time the government reopened (Chart 4).

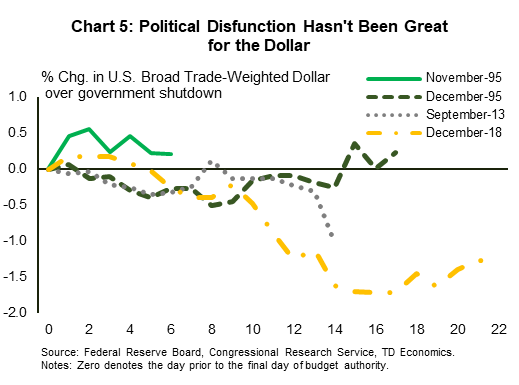

The temporary weakness in equities markets is reflected by a simultaneous move into safe-haven assets and a decline in treasury yields. One exception to this was in 2013, when treasury yields increased modestly, reflecting uncertainty surrounding debt ceiling negotiations. Previous shutdowns have also resulted in a period of weakness for the U.S. dollar. The greenback lost 1.0% and 1.7% during the 2013 and 2018 episodes, but the decline in those occasions was exacerbated by political factors including looming debt ceiling negotiations and the trade war, which dominated headlines (Chart 5).

Costs May Be Small, but Still Annoying

While the economic and financial costs are likely to be small, the involuntary work stoppage within a wide range of government agencies and services will create inconveniences for Americans. This occurs in everything from closures of national parks and museums, delays in tax refunds, suspension of non-emergency passport and visa processing, as well as delays in economic data published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Census Bureau, and Bureau of Labor Statistics. On the latter, the two most important data releases covering the month of September are the employment report – released Friday, October 6th – and the consumer price index (CPI) – released Tuesday, October 17th. Even if the government is reopened before these releases, analysts could still be waiting some time for the data, given that government statisticians would need time to collect and collate it. Naturally, the more time that passes on the shutdown, the harder it will be for economists, financial market participants, and monetary policy makers to gauge economic conditions and make sound decisions.

Lastly, but importantly, certain operations among other prominent government agency would be impacted from a shutdown, including the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) (for more details please see Table 1 in Appendix).

Bottom Line

Although the economic impacts from government shutdowns have not been grave over the years, this relies on agreements being struck in relatively short order. The direct negative impact to the economy would build with time, as would the indirect effects via market sentiment and business confidence. Our recently published forecast does not incorporate any material shutdown in length.

Some have postulated that negotiations will allow parts of the government to be funded on a piece meal basis, with priority given to military and other critical spending. However, this still would have to factor in the triggers set in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. In the extreme event that the shutdown lasts through the fourth quarter, given other headwinds, it could be enough to push economic growth into negative territory. While growth would be made up in future quarters, it could still serve to increase economic fragility.

Table

| Agency | Economic and Social Implication |

| Economic | |

| Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and U.S. Census Bureau | The reporting of pertinent economic data could be delayed. This will impair the Fed's ability to monitor changes in economic activity and implement appropriate changes in monetary policy at a time when the central bank is trying to curtail the highest level of inflation in 40-years. |

| U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) | Many of the SEC's functions will be halted while stock markets will remain open. |

| U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) | Business loan applications will not be reviewed which could delay small businesses plans for hiring and capital expenditures. |

| Internal Revenue Service (IRS) | Despite normal operations continuing, the government shutdown in 2013 saw extensive delays in income and Social Security number verification which impacted mortgage and loan applications. Moreover, tax payments could be delayed which could exert drag on consumer spending should a shutdown persist. |

| Housing | |

| Federal Housing Administration (FHA) | With the FHA shutting down, mortgage loans that require manual review will be unable to be processed. This could exert further drag on housing market activity should a prolonged shutdown occur. |

| National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) | With the flood insurance program set to expire on September 30th, it is estimated that 1300 home sales per day could be delayed if flood insurance is not available. |

| Climate Change | |

| Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) | Delays for infrastructure grants under the BIL would be a negative for business investment in the event of an extended shutdown. |

| Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) | Delays in the allocation of grants and loans under the IRA could postpone planned capital expenditures. |

| Health Care | |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | NIH would be unable to accept new patients and the allocation of research grants could be ceased; however, research activities would continue. |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | The distribution of food stamps would be impacted as the Agriculture Department (USDA) is only authorized to send out benefits for 30 days after a shutdown commences. |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Both agencies could halt or delay inspections akin to the 2013 and 2018-2019 experiences resulting in illness and increased strain on hospitals. |

| Recreation | |

| National Park Service (NPS) | In 2013, national parks closed resulting in an estimated loss of $500 million in revenue. In 2018, however, many parks remained open with limited services available imposing multiple social costs on visitors. |

| Transportation Security Administration (TSA) | A prolonged shutdown could reduce staff which would complicate travel plans and increase security concerns for travelers. |

End Notes

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. https://www.crfb.org/papers/government-shutdowns-qa-everything-you-should-know

- What happens to furloughed employees during a government slowdown? https://federalnewsnetwork.com/government-shutdown/2023/09/what-happensto-

furloughed-employees-during-a-government-shutdown/ - The post office is independently funded through the sale of its goods and services, therefore it will not be impacted by the shutdown. https://www.reuters.

com/world/us/us-government-shutdown-what-closes-what-stays-open-2023-09-21/ - What impact did the lapse of appropriation for some federal agencies have on January employment data? https://www.bls.gov/bls/what-impact-did-thelapse-

of-appropriation-for-some-federal-agencies-have-on-january-employment-data.htm - The Effects of the Partial Shutdown Ending in January 2019. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-01/54937-PartialShutdownEffects.pdf

- Impacts and Costs of the October 2013 Federal Government Shutdown. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/reports/impacts-andcosts-

of-october-2013-federal-government-shutdown-report.pdf - National Association of REALTORS. https://narfocus.com/billdatabase/clientfiles/172/2/4787.pdf

- Here’s what happens when the government shuts down. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/09/23/government-shutdowns-can-wreak-more-havoc-than-you-think-00117725

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: