Location, Location, Location -

Shelter Costs Drive Metro Inflation Differences

Admir Kolaj, Economist | 416-944-6318

Date Published: December 7, 2021

- Category:

- Us

- Real Estate

- Consumer

- State & Local Analysis

Highlights

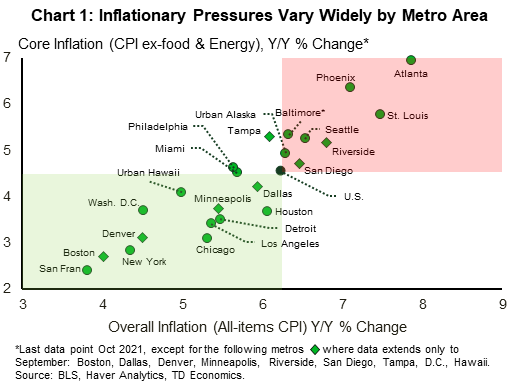

- Red-hot U.S. inflation continues to grab headlines, but a look at metro-level data shows that price pressures vary widely across the country. Metros like Atlanta, Phoenix and St. Louis are experiencing rapid inflation in the 7-8% range year-on-year (y/y), while several of the largest U.S. metros such as New York, San Francisco and Boston are at the low end (around 4% y/y).

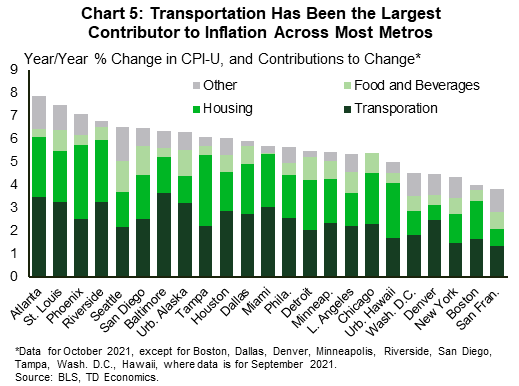

- Transportation has been the single-biggest contributing force behind the run-up in inflation across most metro areas, fueled by price hikes for vehicles and gasoline.

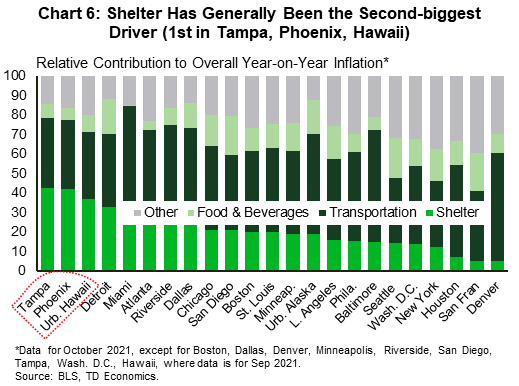

- Shelter, a weighty category in the consumption basket, has generally been the second-largest source of inflation across the 23-metro area cohort, except for in Tampa, Phoenix, and Urban Hawaii, where it is the top driving force.

- Inflation has been hottest in metros where shelter sizzles. Market-based measures indicate that there's more upside for shelter costs ahead. Given its potential to put additional upward pressure on inflation, this category will bear careful watching in the months ahead.

The recent run-up in inflation has been a hot topic, but price pressures are not even across the country. The basket of consumer goods and services used to measure inflation in the consumer price index (CPI) is a weighted index of prices for things like food, shelter, transportation, apparel, and medical care. The importance of each of these categories in the basket varies across regions, as does the rate of price growth for various goods and services. For example, the shelter category tends to make up a bigger piece of the consumption basket in areas where housing is expensive, ranging from a high of 45% in the San Francisco metro, to a low of 30% in Detroit.1 Of course, the rate of shelter inflation also varies across cities, contributing to different rates of overall price growth.

In this report we examine inflationary pressures for urban consumers in the 21 largest U.S. metro areas, along with urban Alaska and Hawaii. In tune with the national experience, all metros have seen a run-up in inflationary pressures, but the degree of acceleration varies considerably (Chart 1). While overall inflation was running at close to 8% in Atlanta in October, it was less than half that pace in San Francisco (3.8%). Other hot inflation metros include Phoenix and St. Louis, while New York and Boston are on the cooler side like San Francisco.

Table 1: Food and Inflation

Table 1 shows the y/y rate of food inflation for July 2020 and the most recent reading as of this year for 23 metros across the country. The last observation for most metros is October 2021, but for Boston, Dallas, Denver, Minneapolis, Riverside, San Diego, Tampa, D.C., Hawaii the data only goes out to September 2021. The table shows that many of the metros that were experiencing strong food inflation by the middle of last year (or soon after the onset of the pandemic), such as Miami, Hawaii, Tampa, Boston and Riverside, now rank at the low end of the food inflation scale. Conversely, many of the metros that were experiencing more muted food inflation by mid-2020, such as Detroit, St. Louis, and Dallas, are now experiencing above-average food inflation.

| Y/Y % Chg. | Mid-2020 | Recent |

| Jul 2020 | Sep/Oct 2021 | |

| U.S. | 4.1 | 5.3 |

| Seattle | 5.2 | 8.1 |

| San Diego* | 6.0 | 7.6 |

| Urban Alaska | 5.3 | 7.0 |

| Detroit | 1.7 | 6.8 |

| St. Louis | 2.6 | 6.4 |

| Dallas* | 2.3 | 5.7 |

| Minneapolis* | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| Los Angeles | 4.7 | 5.6 |

| San Fran | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Houston | 2.9 | 5.2 |

| New York | 4.3 | 5.2 |

| Chicago | 3.8 | 5.2 |

| Riverside* | 6.6 | 4.1 |

| Wash. D.C.* | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Philadelphia | 4.4 | 3.6 |

| Boston* | 7.2 | 3.5 |

| Denver* | 5.2 | 3.4 |

| Phoenix | 3.6 | 3.2 |

| Baltimore | 3.8 | 3.1 |

| Tampa* | 6.8 | 3.0 |

| Urban Hawaii* | 6.9 | 2.6 |

| Atlanta | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Miami | 8.2 | 0.4 |

Inflation data is released at different times for different metros, and 9 of the 23 metros presented in Chart 1, including Boston, San Diego, and Tampa only have data through September 2021. Given where inflation trends have been heading, these nine metros would likely rank somewhat further up the inflation curve if October data was available. An acceleration in inflationary pressures for a few subcategories that are available through October, such as energy and shelter, reaffirms this notion.

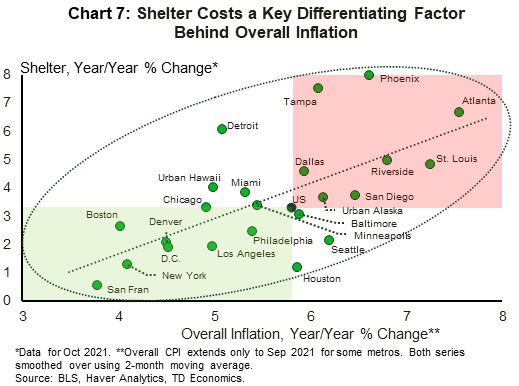

Price increases for food, energy, transportation, and shelter have all contributed to the run-up in inflationary pressures across the 23 metros, although to different degrees. Transportation has generally been the largest source of inflation across most metros, with shelter typically a close second. That said, shelter (which tends to take up a much larger part of the consumption basket relative to transportation) has been the biggest differentiating factor when it comes to overall inflation. The metros with the hottest inflation are typically those that have seen the largest shelter cost increases.

Food Inflation Mixed, Energy Inflation up by Double Digits

Food and energy are two broad categories that can be quite volatile and are typically excluded when trying to gauge underlying inflation trends. However, they tend to account for a little more than a fifth of the consumer basket, and hefty price hikes in these categories still weigh on consumer purchasing power.

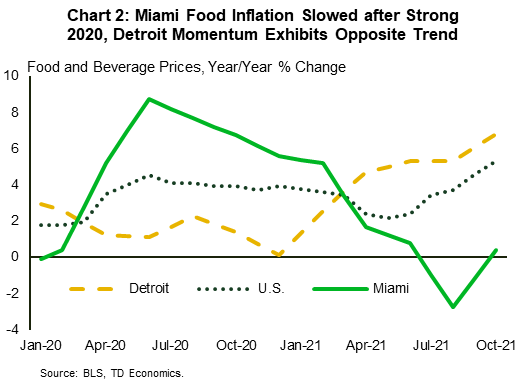

Food has the larger weight of the two (averaging at around 15% across the 23 metros). Inflation in this sector has had a choppy ride over the past twenty months. Prices surged soon after the onset of the pandemic as consumers shifted to eating more meals at home, boosting demand for food at grocery stores. This period gave way to some normalcy, with monthly food price increases relatively muted between July 2020 and March 2021, only to pick up steam again in the months that followed.

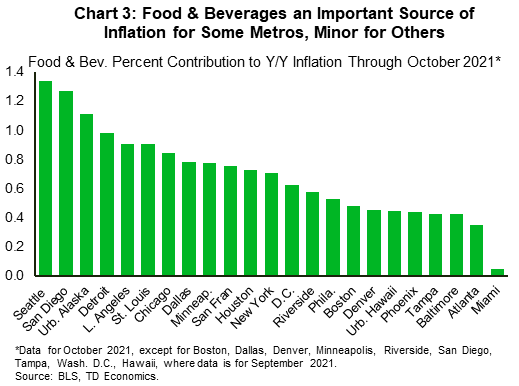

This pattern has been relatively consistent across most metros examined in this report. What stands out is the fact that price pressures in metros that recorded sharper increases during the early phases of the pandemic appear to be more muted this year. Conversely, several of the metros that recorded little food inflation last year, have seen pressures pick up more aggressively in recent months (see Table 1 and example in Chart 2). While base-year effects are at play, the reversal in momentum is also likely the result of a rebalancing in prices – large deviations in food prices across regions are unlikely to be sustained indefinitely. Ultimately though, the different price cycles mean that food inflation has been an important contributor to overall inflation in some metros this year (i.e., Seattle, San Diego, Urban Alaska, Detroit – contributing more than one percentage point to overall inflation), and much less so in others (i.e., Miami, Atlanta, Baltimore, Tampa) (Chart 3).

For energy, the storyline is more straightforward, with the direction of energy inflation the same across all metros. The scale of price increases, however, varies from around 40% year-on-year (y/y) in Minneapolis and Houston, to the lower 20-25% range in Urban Alaska, Phoenix and Philadelphia (Table 2).

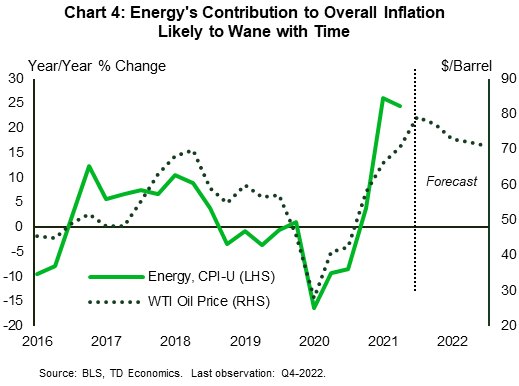

Energy includes things like motor fuel (i.e., gasoline) and household energy (i.e., home heating fuel, electricity, natural gas), which together amount to roughly 6% of the consumer basket across the group. Motor fuel inflation, which is more closely correlated to oil prices, is the hottest of the two (Table 2). Price growth for household energy is much lower but has been gathering momentum across the cohort. By autumn, inflation in this category was still running below 10% y/y in ten metros, and between 10% and 22% in another dozen metros, with Minneapolis the only metro above the 30% threshold. The energy price environment remains uncertain, especially now with the emergence of the Omicron COVID-19 variant. But overall, we expect the runup in energy price pressures to prove transitory. We expect energy prices to become a drag on headline CPI by the middle of next year (Chart 4).

Table 2: Energy Inflation

Table 2 shows inflation in y/y terms for the CPI energy category and two subcategories (motor fuel and household energy) for the United States and 23 metros across the country. The data is for October 2021. The table is ranked based on the broader energy category from high to low. While energy inflation in the U.S. was running at 30% y/y in October, several metros, including Minneapolis, Houston, Chicago, Dallas, were above this mark (35-42% range). At the low end of the scale are Urban Alaska, Phoenix, Philadelphia and San Francisco, with energy inflation in these metros running in the 20-25% y/y range. Tilting over to the energy subcategories, the table reveals that inflation is hottest in motor fuel (40-60% range). Inflation in household energy is relatively more muted and is running below 10% y/y for ten metros and between 10-20% for another ten metros. Household energy inflation is running above 20% in only three metros: Riverside (21%), Houston (22%) and Minneapolis (31%).

| Y/Y % Chg. | Energy* | Energy Subcategories | ||

| Motor Fuel | Household Energy | |||

| Oct-21 | Oct-21 | Oct-21 | ||

| U.S. | 30.0 | 49.6 | 11.2 | |

| Minneapolis | 41.8 | 52.9 | 31.2 | |

| Houston | 38.5 | 59.7 | 21.5 | |

| Chicago | 36.1 | 55.4 | 20.1 | |

| Dallas | 35.9 | 58.7 | 18.1 | |

| Denver | 35.2 | 60.0 | 7.0 | |

| Boston | 33.3 | 53.4 | 20.3 | |

| San Diego | 33.1 | 42.4 | 19.1 | |

| Riverside | 31.7 | 40.6 | 21.0 | |

| St. Louis | 31.2 | 58.1 | 8.9 | |

| Los Angeles | 30.0 | 39.4 | 16.9 | |

| Urban Hawaii | 28.8 | 38.5 | 17.8 | |

| Atlanta | 28.2 | 55.5 | 5.6 | |

| Miami | 28.1 | 48.2 | 6.1 | |

| Tampa | 28.0 | 51.0 | 9.0 | |

| Baltimore | 27.4 | 43.8 | 12.1 | |

| New York | 27.2 | 49.2 | 14.4 | |

| Wash. D.C. | 26.6 | 42.9 | 12.4 | |

| Detroit | 26.5 | 55.7 | 6.9 | |

| Seattle | 25.8 | 42.9 | 4.6 | |

| San Fran | 25.0 | 39.5 | 11.8 | |

| Philadelphia | 24.4 | 41.1 | 11.5 | |

| Phoenix | 23.3 | 46.8 | 3.4 | |

| Urban Alaska | 19.7 | 53.4 | -5.7 | |

Transportation Has Been the Biggest Source of Inflation Across Most Metros

Transportation prices have been the biggest contributing factor to inflationary pressures over the past year (Chart 5). Digging into the details shows that the two key culprits behind the strong runup in transportation prices are motor fuels (covered in the prior section) and car prices.

Car prices have been driven higher by a shift in consumer demand away from public transit to private transportation. A semiconductor shortage, meanwhile, has weighed on auto production, leading to very lean inventories for new cars. Against a healthy consumer demand backdrop, car buyers have had tilt to the used car market. Used vehicle prices have seen the biggest increases as a result and are up close to 40% versus pre-pandemic levels (26% y/y). New vehicle prices are also up around 10% (both from pre-pandemic levels and y/y), after many years of relatively flat prices. However, new car price momentum has been stronger in a handful of metros such as Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Seattle. When it comes to the 'car insurance' component of transportation, the Miami metro, which has seen a notable increase in costs (18% y/y), is the only main outlier. For the rest of the group, car insurance prices are generally either slightly below or not notably higher from year-ago levels.

Inflation Hottest in Metros Where Shelter Sizzles

Shelter, which carries a heavy weight in the consumption basket, has been the second biggest source of inflation this year across most metros. In Tampa, Phoenix, and Urban Hawaii, it has been the top contributor (Chart 6).2 This category can be further split into "rent of primary residence" and "owner's equivalent rent". The latter is simply a measure of what owners would hypothetically pay if they were to rent their home.

Housing affordability constraints and pandemic-related shifts in population appear to have played an important role in driving shelter inflation. Highly urbanized and more expensive housing metros such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, have recorded slower shelter inflation. Meanwhile, smaller, cheaper (and often warmer) markets like Tampa, Phoenix, Atlanta, and Detroit have seen much stronger shelter inflation over the past year. The main point to highlight is that shelter has been a key differentiating factor in overall inflation rates across metros, in part because of its significance in the consumption basket. Indeed, the metros that have seen the strongest run-up in shelter costs also tend have the highest overall inflation (Chart 7).

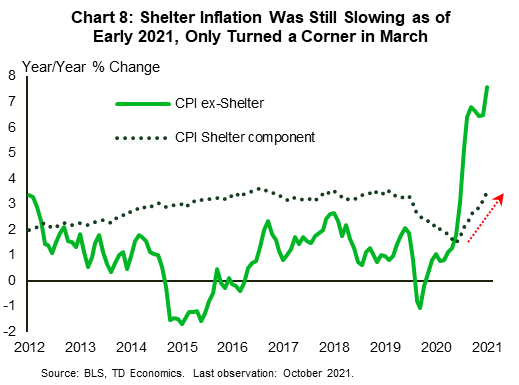

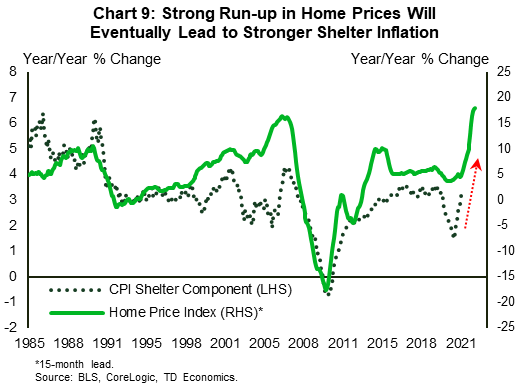

Shelter is also likely to be an increasingly important source of inflation going forward. Shelter inflation pressures were slower to build, only turning a corner by March of this year (Chart 8). At the same time, the recent acceleration in this category appears rather unremarkable, with prices up only 3.5% y/y by October. That said, market-based measures show much stronger gains in both rents and home prices, suggesting that pressures have more room to build (Table 3). Indeed, shelter costs are likely to rise further as a lagged response to the strong runup in home prices (Chart 9). A shortage of housing inventory, and multifamily vacancy rates that are already below pre-pandemic levels across metros (with San Francisco and Minneapolis being the only two exceptions), further support this narrative.

Market-based measures for home price and rent growth, in combination with the weight that shelter takes in each metro (see Table 3), suggest that shelter is likely to be a significant source of inflation ahead for metros such as Phoenix, Tampa, Riverside, San Diego, Atlanta, and Denver, and less so for others such as Baltimore, Chicago, and urban Alaska. Note, however, that the selection of other market-based measures may lead to somewhat different results. For instance, with respect to home price growth, Redfin metrics tend to show stronger growth in Urban Alaska/Anchorage and softer growth in San Francisco compared to the Zillow measure.

Table 3: Shelter Component Likely to Keep Some Upward Pressure on Inflation

Table 3 shows information related to shelter inflation for 23 metro areas. The information is displayed in 5 columns. The first four columns are year-over-year percent changes in 1.) median home values (as of Q3-2021), 2.) the CPI component of Owner's equivalent rent of residences (Oct 2021), 3.) Multifamily rent index (Q3-2021) and 4.) the CPI component of rent of primary residence (Oct 2021). The metros that generally rank highest in all four of these categories are Phoenix, Tampa, Atlanta. The metros that generally rank low on most of these measures are Urban Alaska, Washington D.C., New York, Minneapolis, Philadelphia and Houston. The last column presents the weight of the shelter component in the CPI basket. With respect to the latter, the metros where shelter carries a substantial weight in the CPI basket include San Francisco, Miami and Urban Hawaii (all above 40%). At the other end of the spectrum are metros such as Detroit (30%), along with St. Louis, Urban Alaska, and Washington D.C. (all below 33%).

| Y/Y % Chg. | Price growth | CPI component | Rent growth | CPI component | Shelter CPI weight (%) | ||

| Median home value (Zillow) | Owners' Equivalent Rent of Residences | Multifamily rent Index (CoStar) | Rent of Primary residence | ||||

| Metro area | Q3-2021 | Oct 2021 | Q3-2021 | Oct 2021 | 2021 | ||

| Phoenix | 32 | 9.2 | 23 | 5.0 | 35.0 | ||

| San Diego | 26 | 3.6 | 13 | 3.2 | 36.0 | ||

| Riverside | 26 | 4.3 | 15 | 4.9 | 37.9 | ||

| Tampa | 26 | 8.2 | 25 | 8.3 | 38.5 | ||

| Seattle | 23 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.7 | 36.3 | ||

| Atlanta | 22 | 6.3 | 19 | 7.5 | 33.2 | ||

| Denver | 21 | 4.3 | 13 | 2.6 | 36.2 | ||

| Dallas | 21 | 4.4 | 14 | 4.0 | 36.3 | ||

| Los Angeles | 19 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.5 | 40.1 | ||

| Detroit | 18 | 6.3 | 8 | 6.3 | 29.5 | ||

| San Fran. | 18 | 0.8 | 6 | -0.4 | 45.2 | ||

| Philadelphia | 17 | 1.2 | 9 | 2.3 | 33.0 | ||

| Houston | 17 | 1.5 | 9 | 1.3 | 33.4 | ||

| Boston | 16 | 2.7 | 10 | 1.5 | 38.3 | ||

| Miami | 16 | 3.7 | 15 | 3.0 | 42.8 | ||

| St. Louis | 16 | 2.9 | 7 | 3.8 | 31.8 | ||

| Urban Hawaii | 15 | 2.6 | 11 | 2.1 | 41.2 | ||

| Minneapolis | 14 | 3.3 | 3 | 2.5 | 33.8 | ||

| Wash. D.C. | 14 | 1.7 | 9 | -0.3 | 32.7 | ||

| New York | 14 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.2 | 39.3 | ||

| Baltimore | 14 | 2.4 | 12 | 0.0 | 35.8 | ||

| Chicago | 14 | 2.6 | 8 | 2.6 | 33.8 | ||

| Urban Alaska | 4 | 3.4 | 9 | 2.2 | 31.8 |

The Bottom Line

National inflation statistics tend to grab the limelight, but inflation varies by region. Over the past year, shelter inflation has been a key differentiating factor for inflation across metros. Metros that have seen the strongest run-up in shelter costs include Phoenix, Tampa, Atlanta and St. Louis. Meanwhile some of the nation's largest metros, such as San Francisco, New York, D.C. and Boston, rank lower on both shelter and overall inflation. With market-based price metrics pointing to additional upside for shelter inflation, this category has the potential to become an increasingly important source of inflation and will merit close attention in the months ahead.

End Notes

- Abbreviated from San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA. All metro areas are abbreviated in similar fashion in the text (i.e., by writing only the name of the city that leads the metro). Another example: Riverside refers to the Riverside–San Bernardino–Ontario, CA metropolitan area.

- Shelter is a subset of housing; it excludes elements such as household energy and home furnishings from the latter.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: