Market Insight

The Economic Outlook Upgrade and Yields

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: March 4, 2021

- Category:

- US

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- The continued improvement in economic growth prospects in the U.S. has forced government bond yields to their highest levels since the start of the pandemic.

- The Federal Reserve has not hinted at an upcoming change in policy, but that hasn’t stopped financial markets from expecting an earlier removal of monetary support.

- The upward trend on yields should continue as vaccinations pave the way for a strong growth rebound in the coming quarters.

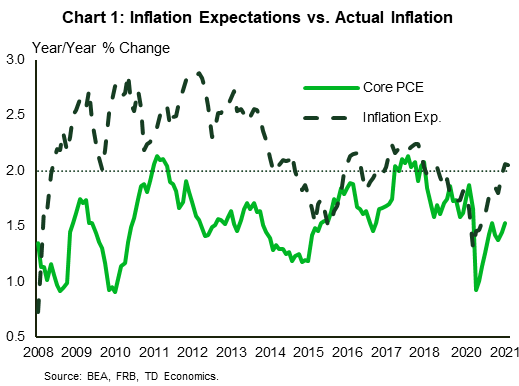

Expectations for the future are brightening with each passing day, as vaccine efforts make further inroads and governments keep their foot pressed against the fiscal accelerator. Just when you think equity markets have peaked, new highs get hit. Commodity markets are flying high again, even among the most precarious – energy. And business and consumer sentiment indices are beginning to reflect higher expectations for economic growth. Little wonder that inflation expectations have moved in parallel to breach the critical 2% threshold (Chart 1). We have previously noted that the economic recovery dynamic would reinforce a widening spread in bond yields, and those forces have come through swiftly. We’re not done yet, even if the bond market may have gotten a little ahead of itself in the near-term.

Expectations for the future are brightening with each passing day, as vaccine efforts make further inroads and governments keep their foot pressed against the fiscal accelerator. Just when you think equity markets have peaked, new highs get hit. Commodity markets are flying high again, even among the most precarious – energy. And business and consumer sentiment indices are beginning to reflect higher expectations for economic growth. Little wonder that inflation expectations have moved in parallel to breach the critical 2% threshold (Chart 1). We have previously noted that the economic recovery dynamic would reinforce a widening spread in bond yields, and those forces have come through swiftly. We’re not done yet, even if the bond market may have gotten a little ahead of itself in the near-term.

Valuing Multiple Trajectories

Despite the improved outlook, Federal Reserve Chair Powell spoke in front of Congress last week, delivering a very cautious tone. The focus was on the here-and-now, with only a formal nod to an improved outlook. This is a traditional communication approach for central banks. The future is embedded within a theoretical framework, but the present is one marred with 10 million unemployed workers, following the deepest recession in generations. The introduction of successful vaccines has caused economic risks to recede, but not be eliminated. And the economy that emerges on the other side will be marked with structural changes that are not yet fully understood. Powell hinted at this by noting that the real unemployment rate is closer to 10% (instead of 6.3%) when the rate is adjusted for the “many unemployed individuals [that] have been misclassified as employed.”

For a central banker, this is the point in the economic cycle that stands at the fork in the road. It’s premature to place monetary policy on a single path at the risk of having to reverse course. This would create detrimental financial volatility and undermine market confidence. Recall that in 2013, Fed Chair Bernanke casually mentioned that the Fed was considering an end to QE and yields shot up 132 basis points in just 4 months. Simply ideating about the removal of monetary support ends up solidifying this outcome within the market mind-set. This places the central bank in a position of waiting for a clear road map within the data before choosing its path. In contrast, financial market participants can’t afford to be so patient. They will price the most likely path today, and listen for confirmation of those expectations from central bank communications in the months ahead.

Defining the Most Likely Recovery Path

The basic premise of mapping out the recovery is rooted in traditional economic theory – to achieve sustained inflation around 2%, the economy must eliminate excess capacity. Of course, the central bank’s job is to adjust policy today for the economic environment that will exist in 12 to 18 months. This concept manifests as the gap between market inflation expectations versus the actual data that we show in Chart 1.

There’s no dispute among the ranks that the economic recovery will be firmly rooted in that time period. However, this is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for higher inflationary pressures. One of the reasons that the Federal Reserve continues to show a high degree of patience is because we’ve been here before.

Post-Global Financial Crisis, inflation expectations also rose. But, as year after year passed, the evidence of worrisome inflation failed to materialize in the hard data. That led to a decade-long journey of trying to maintain inflation at the elusive 2% target. This time around, the central bank has set the bar even higher by communicating that they don’t just want to get to 2%, but exceed it in order to be convinced of its sustainability.

And, there’s another twist to the plot. There has been far greater emphasis on the labor market as the gauge for that outcome, rather than advances in economic output. A high degree of excess unemployment and underemployment acts as an automatic anchor on inflationary pressures – a lesson reinforced from the previous economic expansion. It revealed that the connection between the GDP output gap and inflation had diminished. The output gap, itself, is a hotly debated unobserved variable, formed by a series of assumptions around labor market and productivity trajectories. Following the Global Financial Crisis, as the U.S. economy reached what was believed to have been capacity constraints, inflation remained muted. It was only when the scarcity of spare workers moved beyond historical levels that inflation finally hit 2%. That point occurred in 2018, ten years after the onset of the financial crisis. The unemployment rate was at a mere 4%, or 0.6 percentage points below estimates of full employment at that time.

This experience has inspired a rethink of the central bank playbook. Rising economic growth and wages are not shared equally across society. And, this cycle has created a unique set of inequality challenges on the policy front. Maximum employment is no longer considered to be when the national unemployment rate reaches a certain theoretical level. The aggregate is an imprecise measure of the whole. Labor market differentials in gender, race, geography, and income cohorts over history reveal that a greater degree of ‘tightening’ in the labor market can occur to help disadvantaged groups, in turn creating more sustainable inflationary forces. As an example, the female participation rate for the core age cohort (25-54 years) was on a steady downtrend until late 2015. Only then, with an economy-wide unemployment rate of just 5%, did the labor market dynamics entice this group of workers back.

In the current cycle, the divide is worse. Disadvantaged groups are heavily skewed to lower wages. In turn, this is skewed to women and racialized groups. Central banks are emphasizing this labor market divide more than ever as a contributor to the muted link between the job gains and inflation. As a result, central banks may choose to test the lower limits of the unemployment rate in this cycle.

Let’s look at how this can impact inflation. First, the pandemic creates an untested theoretical framework for the economic recovery. Judgement always overlays model outputs, but this may prove more the case this time around. Though central banks are still using models, Powell has stated that, “we are not acting on forecasts.” This is a vast departure from the past. Previously, it would have leaned on the 12 to 18 month economic outlook to guide policy adjustments, given the lag that exists for interest rates to ripple through the economy. Now that the Fed is intending to wait for the data to explicitly reveal itself, we must map out a more delayed fed funds profile than in the past.

Mark Your Calendars

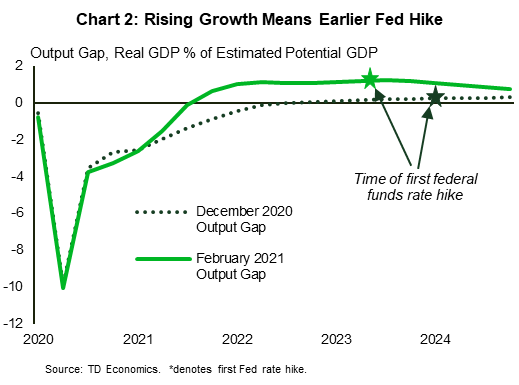

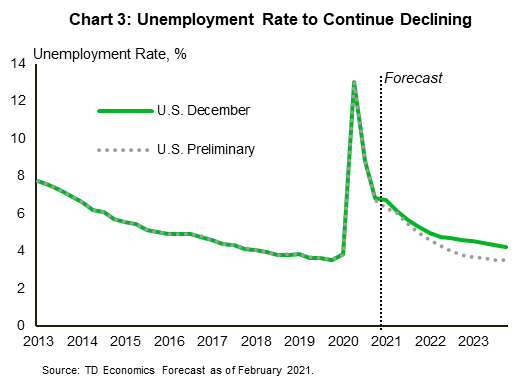

Our updated economic outlook shows that the U.S. economy should be moving into excess demand space by early 2022, and the unemployment rate will be sub-4% in mid-2022 (Chart 2). This is the point at which we think the economy will really show clear signs of heating up. From the middle of 2022 to the middle of 2023, we expect further job gains to push the employment rate down to historic levels (Chart 3). This translates to core PCE inflation averaging just over 2% for that one-year time frame, opening the door for the Fed to hike rates. Market participants are increasingly incorporating this view. Our regular readers know that market pricing had been far too pessimistic on the Fed outlook. Over the last few months, pricing has swiftly begun pricing earlier rate hikes, as expectations build towards a large fiscal package from the Biden administration.

The question now is: how much higher can yields go? This depends on how high inflation goes. If we are correct and core inflation overshoots 2%, but remains below 2.5%, the upper-bound of the Fed policy rate will likely reach a high of 2% in 2026. As time moves one, this would eventually bring the U.S. 10-year yield to around 2.2%, from 1.5% today.

The Double-Edged Sword of Overshooting Inflation

Given the sustained period we expect for excess demand, we are often asked whether the economic rebound can set inflation on an uncontrollable path. With the Fed being very patient this cycle and allowing the economy to run hot, higher-than-projected inflation is a risk. However, it’s a matter of what you consider an “uncomfortable” risk.

First, the risks around inflation are asymmetric. Central banks have proven and tested tools to address higher inflationary pressures, but there is little they can do if inflation remains depressed. There is more at stake from the “Japanification” of the economy, which is the predicament Europe is increasingly facing. If given the choice, central bankers would prefer to address the upside rather than the downside of inflation. Should inflationary dynamics get ahead of the central bank, the policy rate can be adjusted in a swifter manner. There is certainly plenty of room to the upside on the policy rate, but very little daylight left on the downside should the opposite situation materialize.

Second, central banks have a long and credible history of refining communication to market participants. The odds of a 1980s redux are low. Back then, CPI inflation reached peaks of roughly 15% and the Fed’s policy rate likewise rose to 22%. The central bank lacked the sophistication of today in providing clear guidance of inflation targets. Over time, the Fed stopped targeting the money supply and focused on inflation targeting, reinforced by an explicit 2% objective. The steadfast commitment on this front brought down inflation expectations and actual inflation to the low levels that we have become accustomed to over the last decade.

This means that an inflation overshoot today would be characterized as being closer to 3% compared to the double-digits of the past. And, there are still structural forces at work that are conspiring to tap down pressures, such as aging demographics and digital adoption.

However, the central bank doesn’t get a carte blanche on its patience, which is why we believe 2023 offers a good trigger point. This is a year in advance of the current forward guidance of central banks. Low interest rates are already fueling asset price inflation and risk-taking behavior. A balance must be struck to ensure morale hazard isn’t engrained within market behavior marked that creates asymmetric risks on the other side of the ledger. We’ve been here before. Most recently under the tutelage of Chair Greenspan and Chair Bernanke. Their efforts to discount the past and experiment with the bounds of maximum employment created financial risks that were extremely counterproductive. We are already seeing financial risks develop through high equity valuations, rising home prices, and increasing leverage. And, this is happening very early in this cycle compared to in the later innings of previous cycles. As the central banks test the limits of maximum employment and average inflation, they need to strike the right balance with other aspects of the economy. Macroprudential policies can be a partner here, but too often it’s introduced late to the game and only offers a partial backstop to the impulse flowing from low borrowing costs.

Bottom Line

It has been a year since the start of the pandemic-induced recession. The headway made over the last few months on vaccine development, fiscal supports, and the incredible adaptability of people and businesses has been tremendous. We expect strong economic growth and job gains to continue, and a full recovery to be achieved over the next 1 to 2 years. That is when central banks should consider readjusting policy rates off the basement floor. Though interest rates will rise, it is important to remember that higher rates do not equate to high rates.

In the meantime, the improved economic outlook will continue to be incrementally priced into financial markets. This will edge bond yields higher and reinforcing the curve steepening dynamic we have discussed in previous issues.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.