Market Insight

Policy Rates, to Infinity and Beyond

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Director | 416-413-3180

Date Published: May 5, 2022

- Category:

- U.S

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- The Federal Reserve delivered on a supersized 50 basis point hike. This is likely the first of two more to come.

- The policy rate is still less than half-way to the finish line.

- We expect a swift adjustment to 2% in July. Once inside the neutral range, more cautious 25 basis point increments then become warranted.

- The urgency of coming from behind on inflation must be balanced against the risk of what the economy can bear under one of the most rapid policy adjustments in history.

- If the Fed stays in the fast lane, we would expect to see yield inversion reflect concern of an overshoot.

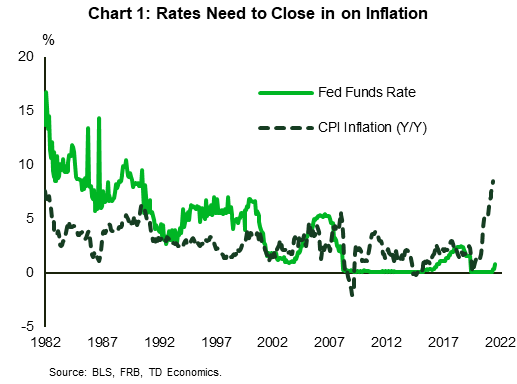

The Federal Reserve accelerated its rate hiking cycle with a 50-basis point hike yesterday. With the policy rate still only at 1%, more supersized hikes are coming. We anticipate the central bank will move twice more in 50 basis point increments, before the window opens to return to quarter-point adjustments. The former allows for a swift recalibration to the lower end of their estimated neutral range, while the latter allows the central bank to monitor the lagged impact of interest rates and quantitative tightening on the economy. Still, with inflation stubbornly high, there is tremendous uncertainty on the final resting place for the policy rate (Chart 1).

In the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections, members expected the policy rate to sit between 1.6% and 2.4% (central tendency) by the end of this year and reach towards 3% by the end of 2023. However, past cycles have shown that the central bank tends to fall short of its end point expectation before cracks appear in economic momentum. Already, U.S. existing home sales have dropped 11% in two months, and this retreat is likely to extend for several more months. A key forward indicator - pending sales - also declined over the same time period. This is not a bad thing. In fact, it’s needed.

Nonetheless, the urgency of coming from behind on inflation must be balanced against what the economy can bear under one of the most rapid policy adjustments in history. An error on the front end of this cycle of having waited too long, can quickly swing into a second error that undermines confidence by overcorrecting. When an economy has already pushed into excess demand territory, the forces needed to quell inflationary pressures require a sustained period of sub-potential (read sub-2%) growth. That thin growth-buffer leaves little margin of error for an overshoot on the downside.

Please Wait: Map is Rerouting

In our recent report (0 to 100 Real Quick), we explained how the Fed’s new operational framework put it behind the eight-ball. It did this by focusing on real-time data and overweighting the downside risks. As the evidence piled up reaffirming the resilience of the labor market and the economy despite each virus-related disruption, other evidence of inflation’s staying power was down played. This ‘patience’ framework pushed aside the standard operating procedure, where policy decisions were based on the economy’s likely trajectory and the related inflationary risks it would present. Now that the central bank is forced to play catch-up, it is also forced to revert to making decisions based on where the economy is going. It needs to make assumptions on how its recent and upcoming interest rate hikes will feed through to the economy and ultimately anchor inflation expectations.

The Fed’s new strategy to tackle inflation was mapped out by Chair Powell in late April when he stated that the Fed was “going to be raising rates and getting expeditiously to levels that are more neutral.” After that, the fine tuning comes into play, as the central bank must decide on how much more is needed to orchestrate the elusive soft landing.

Driving with the rearview mirror

It sounds simple…get rates to neutral. However, this is a complicated task. The range of estimates for neutral by Fed members is between 2% and 3%, which is wide and still subject to further revisions. One reason for this is that the neutral rate is estimated and unobserved. Nobody can definitively say where the neutral rate lies. It’s a theoretical concept that pinpoints a rate of interest that keeps the unemployment rate and inflation stable. Operationally, we only really know what neutral is once it has been passed. It’s akin to driving a car while looking through your rearview mirror – you only know you have missed the highway exit once it’s been passed.

In the last business cycle, the Fed’s policy rate peaked at 2.5%, even though Fed members thought it was headed above 3%. The interest rate-sensitive sectors of the economy had already begun to stall. This led to a quick U-turn to cut the policy rate back to 1.75%. For this reason, we expect the Fed to quickly hike its policy rate to the lower end of the neutral range of 2% by July, before continuing more cautiously as it tests the economy’s threshold.

When I say jump, you say how high

This second stage of the hiking cycle will be trickier than the first. Over the last year, the Fed’s hawkishness has pushed up long-term Treasury yields by about 2%. But at the same time, inflation has risen by more than 4%. The Fed’s shift has not been enough to temper inflation. However, the latter is a lagging indicator, raising the risk that with too rapid of an adjustment, rates could overshoot the ideal threshold that would keep the economy in balance. As former Fed Chair and current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently said, “it will require skill and also good luck.” First off, it’s never comforting that the central bank needs to rely on luck to achieve its goals. Secondly, it implies that bringing down inflation will require more than just the Fed. Think of it this way, if inflation were to stay at 8.5%, the Fed would need to raise rates by over 8% to get the real policy rate into positive territory to sufficiently restrict economic activity. This is where the luck comes in. The Fed needs some of the inflation related to supply disruptions to come off without having to raise rates to such great heights.

Supporting the notion that price gains are not solely a function of strong domestic demand forces, China’s zero-covid policy has maintained tension on supply chains for more than two years since the start of the pandemic. Then along came an unanticipated war in Europe. This is forcing a sudden recalibration of food and energy supply, along with a host of raw materials that were already facing challenges from pandemic disruptions, including shortages of the inputs needed to make semiconductors.

Another price shock could appear at any moment, but the intensity is likely to be smaller going forward. For instance, used vehicle prices increased by 37% in 2021, contributing an outsized 1.3 percentage points to the U.S. CPI measure. While supply is slow to adjust due to ongoing disruptions, companies are increasing investment and production. Consumers have likewise shown their intolerance for an ongoing ascent in prices and, in the past two months, vehicle prices have leveled off. This will impose a downward pressure on overall inflation by year end.

It’s often said that the cure for high prices, is high prices. Elevated inflation and rising interest rates will tighten consumer wallets, even in a persistently solid job backdrop. This should slow demand and ease some of the supply troubles. This combination would open the window for the Fed to slow the pace of rate hikes, which is why we have the hiking pattern shifting to 25 basis point increments in September, moving the policy rate to 2.5% by the end of this year.

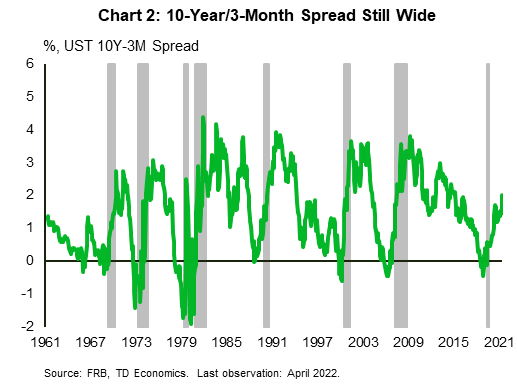

In turn, the risk of yield curve inversion is mitigated – a telltale sign that financial markets are upping the recession probability from ‘maybe’ to ‘most likely’. If, instead, the Fed stays in the fast lane, we would expect to see yield inversion due to investor concern of an overshoot. Although the Fed will certainly need some luck as it tackles inflation, applying a careful approach once it moves past the neutral estimate will be imperative.

Let’s talk recession

There is a lot of client discussion occurring about the risk of recession. History is littered with episodes where bouts of inflation and Fed rate hiking cycles push the economic drivers too far into contraction. Just recently, the spread on the 10-year Treasury yield was briefly eclipsed by the 2-year yield. This implies that markets (for that brief moment in time) thought the Fed was going to take rates too far within the next two years. As the Fed continues to raise rates in the coming months, there’s a good chance the 10-year/2-year spread will flirt with inversion again, and potentially even the more closely analyzed 10-year/3-month spread (Chart 2). The Fed will be closely watching this and may have to slow or end its rate hiking cycle in order to avoid the negative sentiment from creating the outcome they are trying to avoid.

However, let’s entertain the notion that this plane won’t hit a soft landing. The word ‘recession’ is loosely thrown around, but rarely appropriately defined by the analysts using it. There is a big difference between a 2008 experience, and a 2001 cycle. Given that the U.S. economic cycle lacks leverage excesses and risky financial assets of 2008, a policy miss would more likely land us into shallow recession territory. In fact, American households in this cycle are far better positioned to withstand pressure, given they have benefited from a 30% surge in net worth over the past two years, and continue to sit on excess savings, while facing a job market where there are more available jobs than available workers. These metrics leave plenty of buffer to withstand some erosion, without completely upending the cycle into a deep recession. In fact, since economic growth needs to recalibrate below potential to ease pressure on inflation, if it were to marginally overshoot and tread water in shallow negative territory for a short period, it should not be cause for panic. It can accelerate the recalibration. So, don’t fear the recession, only fear the depth and duration.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.