Market Insights:

Ground Control to Major Tom

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: March 28, 2022

- Category:

- US

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Check the ignition, it is time for policy rate liftoff. With the Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada gearing up to hike their policy rates within days, questions abound over how fast and how high rates will go.

- Given the starting point of emergency level interest rates, this will likely be the swiftest pace of rate hikes since 2005. Not to mention, we expect the central banks to simultaneously reduce the size of their balance sheets.

- This has markets moving fast, maybe too fast. The Fed and Bank of Canada will have to be nimble as they tighten policy without derailing the economy. A steady predictable policy path is likely the best way forward given the apparent risks, which include the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

It is countdown to policy liftoff, with the Federal Reserve gearing up to raise interest rates for the first time since 2018. Futures markets have been gradually increasing the probability of rate hikes for months, and even Russia’s aggression on Ukraine was unable to shake that mind-set. We expect the central bank to hike at its March meeting. With inflation serially overshooting expectations, and with economic slack having disappeared, it has no wiggle room to take a wait-and-see approach anymore. The only question remaining is how high will rates go within this normalization cycle?

It is countdown to policy liftoff, with the Federal Reserve gearing up to raise interest rates for the first time since 2018. Futures markets have been gradually increasing the probability of rate hikes for months, and even Russia’s aggression on Ukraine was unable to shake that mind-set. We expect the central bank to hike at its March meeting. With inflation serially overshooting expectations, and with economic slack having disappeared, it has no wiggle room to take a wait-and-see approach anymore. The only question remaining is how high will rates go within this normalization cycle?

Commencing Countdown, Engines On (five, four, three)

Over several weeks, a chorus of Fed members have spoken of the urgent need to raise interest rates. Consumer prices are growing at 7.5% y/y and the labor market is exhibiting a level of tightness not seen in decades. And it is not just product-specific supply chain issues driving inflation. We are now seeing a broad-based move up in prices, ranging from hamburgers to the cost of laundry services to the cost of heating a home. For the Fed, the writing is on the wall – higher interest rates are needed to retain market credibility, anchor expectations and, ultimately, quell inflationary forces.

This has markets fully priced for a Fed hike on March 16th and upwards of 1.5% in interest rate hikes over 2022, even with recent volatility. The last time the Fed lifted interest rates this much in a single calendar year was in 2005, one year before the start of the housing market crash. This time around, the Fed will not only be hiking policy rates, but also reducing its $9 trillion balance sheet portfolio in a more compressed timeframe than the prior period following the Global Financial Crisis. This process, known as Quantitative Tightening (QT), could start as early as next month and would further pressure interest rates higher.

Take Your Protein Pills and Put Your Helmet On

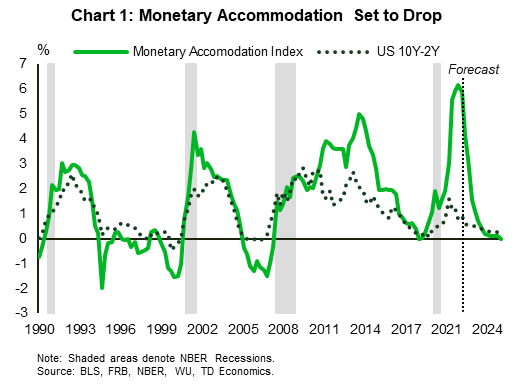

The removal of monetary support isn’t going to come easy. The economy has levered-up on the back of historically negative real interest rates. Indeed, our Monetary Conditions Index (MCI, Chart 1) reached its highest level of stimulus since 1975. For monetary conditions to be return to balanced levels, the Fed needs to move the policy rate to 2%, or higher.

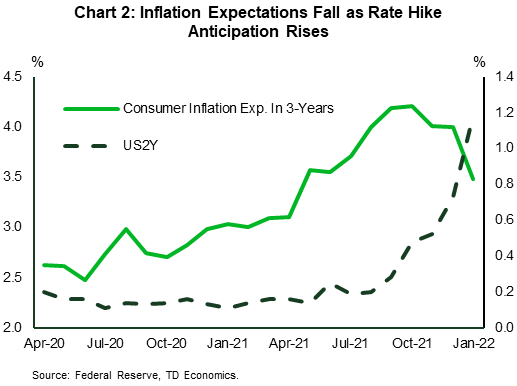

Markets are already responding to the signals. The 2-year Treasury bond yield has risen approximately 1% over the last few months before a single rate hike has been delivered. Yields will rise further in the coming months, feeding through to the broader economy. This is already apparent in mortgage rates. The 30-year fixed mortgage rate has risen 90 basis points since the start of the year, or at twice the rate of change relative to the 30-year Treasury yield. At around 4%, the 30-year fixed rate is already at the highest level in 3 years. Almost in the blink of an eye, and with more to come.

This gives an idea of how rapid normalization can occur once the central bank is deemed to be behind the inflation curve. However, this also raises the risk of undermining market confidence or a formal policy error, as the central bank tries to get back into the driver’s seat. The short-end of the yield curve is rising faster than the long-end, causing the slope of the yield curve (the 10-year/2-year spread) to steadily decline (0.4% currently). Moving too quickly can set in motion the dynamics to invert the curve, which is a harbinger for a recession, typically inverting around 2-years prior. In effect, this would be a signal of a policy error.

When the Fed starts raising interest rates, it doesn’t know the precise level that is necessary to balance the economy (i.e., keep inflation around 2% and maximize employment). If often overshoots the mark and the interest rate sensitive parts of the economy start to roll over. At that point, it is too late to un-ring the bell, as changes in interest rates take up to 18 months to feed through some segments of the economy. In the meantime, past rate hikes continue to weigh on sentiment and the economy, increasing the odds of a recession, or a period of low growth. Getting it perfectly right is like setting down a spaceship orbiting the earth on a diameter of just 7 meters - it can be done, but it requires incredible foresight and technical precision.

To estimate that threshold, we use our MCI and the slope of the yield curve, as both have great track records as recession signals. Using our forecast for both indicators, the Fed could hit that balancing threshold within the next 12 months, and any movement beyond would heighten the risk of recession in 2023/2024. When comparing the normalization of the MCI to its own history, this normalization period would mark one of the quickest, and if the central bank moved even more quickly to align to market expectations, it would afford them even less time to observe whether they are getting too close to confidence thresholds.

The Stars Look Very Different Today

This is one reason why we sit a little behind the market expectation on the rate hike path for 2022. The Fed needs to get rates off the floor, but not necessarily to the ceiling in quick order. In addition, it’ll need to observe the dynamics of QT, which is also occurring much earlier than in the previous cycle. The Fed has two simultaneous, sped-up policy dynamics to monitor. From our perspective, the market has reacted (and slightly overreacted) to the former, but has unlikely factored in the latter.

Gauging the preferred speed limit means that the Fed’s messaging will be closely scrutinized. For most of the last two years, the Fed has delivered a message of patience. It chose to prioritize incoming data versus models that would predict the data’s future progression. This was a departure from their prior reaction function, and that patience has trained markets to follow suit by focusing on real time data. The problem with this approach in a rate hike cycle is that the peak impacts to the real economy can occur with long lags. In some sectors, the full impact is not known until much later. Meanwhile, the near-term inflation metrics will still be coming in on the high side, also reflecting past lags. As an example, sea-bound shipping costs have fallen 65% from the peak last winter. But U.S. producer prices rose in January more than they did in the October to December period, when supply pressures were at their worst. This is because business contracts are set well in advance, and it takes time for benefits to fee through to end-use prices. Those benefits may not be realized until the summer months of this year. The central bank will have to retrain the market’s focus and reaction function, or it will risk moving too quickly or overshooting the degree of necessary tightening.

So far, the Fed hasn’t yet enforced this move away from myopic policy making, which can help to explain why markets may be over predicting the speed and peak of the fed funds rate. However, this is not an unusual occurrence. History shows that financial markets tend to over-predict the central bank’s policy path at the onset of a turn in the monetary cycle, but eventually adjust to their guidance. The difference today is that the Fed is coming from behind the inflation curve and will have to do more heavy lifting than usual to retrain the market’s eye. This process risks serially disappointing market expectations and undermining the market’s perception that the central bank has got it right (i.e., credibility). This makes the upcoming hiking cycle even more precarious, not to mention that risk that evolving geopolitical events can add even more volatility.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.