Multifamily Sector Shows Signs of Improvement, But Headwinds Will Hold Back Pace of Recovery

Admir Kolaj, Economist | 416-944-6318

Date Published: May 4, 2021

- Category:

- U.S.

- Real Estate

Highlights

- The pandemic dealt a heavy blow to the U.S. multifamily market, with vacancies rising and rent growth slowing to a halt by the end of last year. The dispersion of pain, however, varied widely by market and sub-segment.

- Urban centers, which saw an outflow of residents during the pandemic, particularly in large coastal markets, suffered the biggest fallout. Suburban markets on the other hand, have fared generally better, with some even benefiting from the pandemic. Lastly, many markets with warmer climates and more affordable rents, such as those that can be found in the Sunbelt, have generally outperformed in the past twelve months.

- The broader multifamily market is showing signs of stabilization. Demand is improving, and although concessions remain popular, especially in downtowns, slowing rent growth is showing early signs of a turnaround.

- A labor market that’s expected to remain on the mend as the health crisis subsides, will remain supportive to demand for multifamily housing. Meanwhile, a measured and gradual return of workers to the office will also lend a hand.

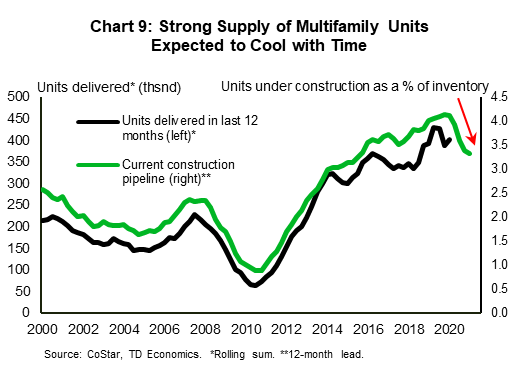

- The delivery of new multifamily units will continue at a high level in the months ahead – a factor that will put some upward pressure on vacancies in the near-term. But with fewer projects started over the past twelve months, a shrinking construction pipeline will eventually result in less product coming to market. This trend, which is likely to emerge at the end of this year, will become more visible in early 2022 and will help ease supply-sided pressures on vacancies and rents.

- Despite an improving outlook later this year and early 2022, structural headwinds are likely to limit the speed of recovery for the multifamily sector. These are related to the country’s changing demographic profile – millennials will increasingly enter the family-forming period, which is likely to favor the single-family market – and the lingering popularity of remote work post-pandemic. The potential for stronger immigration levels, however, could help ease the pressures from these structural headwinds.

The pandemic took a heavy toll on the U.S. economy last year, and the commercial real estate (CRE) market did not escape unscathed. In two prior reports, we looked at the impact on the office and retail segments (see respectively here and here). In this third CRE report, we turn our attention to the multifamily segment.

The narratives surrounding the housing market during the pandemic have gone against the grain, with housing mostly a good news story. Residential sales activity recorded a sharp rebound soon after the onset of the pandemic and remained exceptionally strong, until very recently. Meanwhile, with inventories near record-lows, home price growth accelerated into double-digit year-over-year (y/y) territory. These dynamics led builders to ramp up the production of new homes, with the single-family market the clear winner alongside the pandemic-induced “race for space”. Tilting over to the multifamily market, however, the overall narrative has been decisively more downbeat.

Demand for rental multifamily units pulled back at the onset of the pandemic, with a combination of factors contributing to the decline. Chief among these were the partial shutdown of the economy and increased concerns regarding dense urban living. The closure of many cultural, entertainment and gastronomical establishments, for instance, not only contributed to rising unemployment but also took away some of the allure of living in dense urban areas.

An increased need for more living space alongside a rise in remote work also contributed to lower demand in urban cores and apartment living. Similar to homeownership preferences, rental preferences shifted toward more spacious living arrangements, often in walkable suburban neighborhoods. To be clear, the population shift to the suburbs had already been building momentum since 2013 (see here). But, the pandemic certainly expedited the trend.

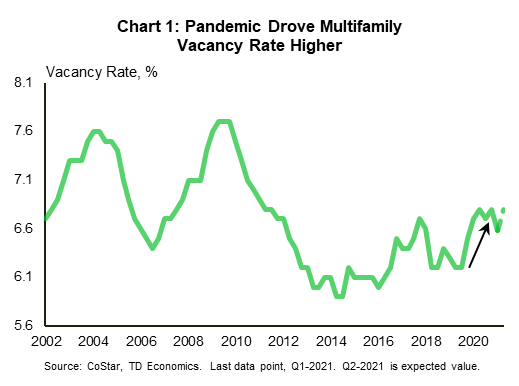

On the other hand, a rich construction pipeline, and the fact that the construction sector was largely unperturbed from COVID-19 work restrictions, resulted in more product hitting the market last year, with the supply of new units surging to an all-time high of around 425,000. A combination of falling overall demand and rising supply led to a surge in the national multifamily vacancy rate (from around 6.3% in 2019 to around 6.8% at the end of last year) and a sharp deceleration in rent growth, dealing a hard blow to the sector (Chart 1). The vacancy rate did record a mild improvement at the start of this year. But, it’s worth noting that given suburban-urban shifts in demand, the vacancy rate in downtown areas remains elevated at over 10%, while in suburbs is has continued to fall to almost 6% - matching record lows of recent years. In addition, despite the overall weak narrative, the multifamily sector is not the most negatively affected corner of commercial real estate, with the office and retail segments faring worse over the past year (Table 1).

Table 1: Multifamily Not the Worst-hit CRE Segment

| Q1-2021 vs. Pre-pandemic period* | Office | Retail | Multi-family | Industrial |

| Vacancy rate (ratio)** | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.05 |

| Rent growth (% Chg.) | -1.4% | -0.1% | 2.2% | 5.3% |

| Price growth (% Chg.) | 0.0% | 0.9% | 2.9% | 7.0% |

Dispersion of Pain Varies

As often is the case with real estate, the narrative can vary widely across markets and sub-segments. The degree to which COVID-19 has negatively impacted multifamily markets throughout the country has been dependent on the pandemic’s reach and measures taken to stem the spread of the virus – factors that are channeled through a weaker economic backdrop and a reduced appeal of dense multifamily living. To this end, several other themes have emerged in the pandemic’s aftermath:

- Warmer and cheaper markets in the south have generally fared better

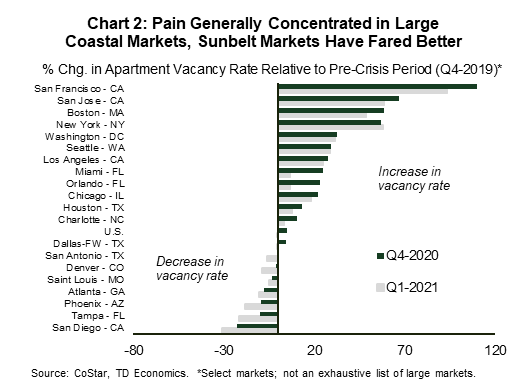

Besides the shift away from urban cores to the suburbs, another important trend observed during the pandemic is the migration in demand to warmer southern markets where rents also tend to be cheaper. In chart 2, we can see that larger coastal markets like San Francisco, San Jose, Boston and New York saw their apartment vacancy rates rise considerably following the onset of the pandemic. By contrast, the vacancy rates of many Sunbelt metros like Houston and Orlando generally held up better, with some even recording an improvement in the past year (i.e. San Diego, Tampa, Phoenix, Atlanta).

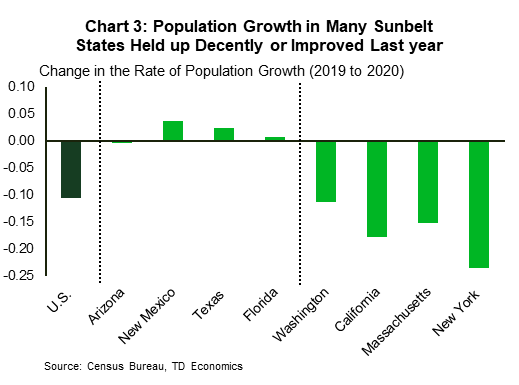

An inflow of residents from other parts of the country has also likely played a role in the outperformance of Sunbelt markets. According to 2020 headline population estimates, population growth for coastal states such as California or New York decelerated sharply last year, whereas population growth for Sunbelt states like Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Florida held up much better (Chart 3). In the absence of more granular population figures, other data sources, such as cross-country rental truck patterns (i.e. U-Haul), shed additional light at the metro level and support the narrative of a population inflow into Sunbelt markets.1 The benefits of an inflow of residents would extend to the rental apartment market, given that a good portion of the new arrivals would seek more temporary (i.e. rental) living arrangements during uncertain times.

- Pain concentrated in higher-end properties

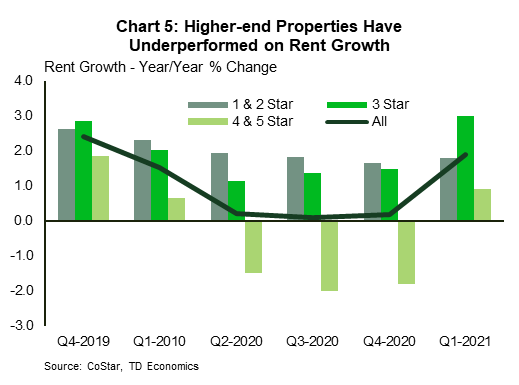

Another important feature of the pandemic is the fact that the pain has been concentrated in higher-end properties, while lower-end properties, such as those classified as 1-3 stars, have held up much better on vacancies and rent growth (Charts 4 and 5). Several elements help explain this bifurcation. For one, negative pressures have been concentrated in markets such as San Francisco and New York, which tilt toward higher-end properties. But, the type of product that came to market last year, which has been heavily slated toward higher-end properties, has also played a role. Note that roughly 80% of all multifamily units that were delivered to market last year were classified as 4-5 star.

The shift toward homeownership in the suburbs has likely also chipped away at higher-end rental demand. Indeed, with jobs in well-payed industries holding up decently during the pandemic (thanks in part to the rise in remote work) and interest rates heading lower, several key ingredients were in place for many Americans to make the leap to homeownership during the pandemic. This is line with the elevated home sales trend soon after the onset of the pandemic.

On the other hand, it’s worth noting that government support programs, such as rent relief, stimulus checks or enhanced unemployment benefits, are lending a hand to lower-end properties. Whereas, the ongoing moratorium on evictions that has been extended to June 2021 is likely masking some of the damage (i.e. unit may be qualified as occupied, but rent may not be getting paid).

- Student and senior housing mark ongoing weak spots

Student and senior housing mark two notable weak spots in the multi-residential space during the pandemic. The underperformance of these two sub-segments is not a surprise. Nursing homes and retirement communities bore a steep health toll during the pandemic. As a result, many seniors likely delayed their planned transition into these communities. Meanwhile, with colleges moving to an online learning model en masse, the number of students living close to school saw a steep decline during the pandemic. Given the cyclical nature of student housing and the lack of long-term commitments, the vacancy rate of this multifamily sub-segment recorded a sharp increase, from about 6% in the pre-pandemic period to over 10% at the end of last year. The shift to online learning, however, is not the only factor. The health crisis’ financial impact on family incomes likely caused some students to skip out on college entirely. To this end, a recent survey found that a quarter of last year’s high-school graduates delayed their college plans.2

Broader Economic Recovery to Lend a Hand to Multifamily Sector

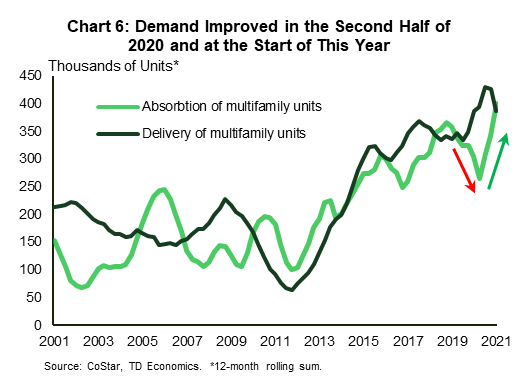

Broad conditions in the U.S. multifamily market have been stabilizing. Demand for apartments managed to improve in the second half of 2020 as the pandemic’s initial shock subsided, with the positive trend carrying over to the start of this year (Chart 6). This positive narrative is supported by elevated online apartment search activity so far this year.3

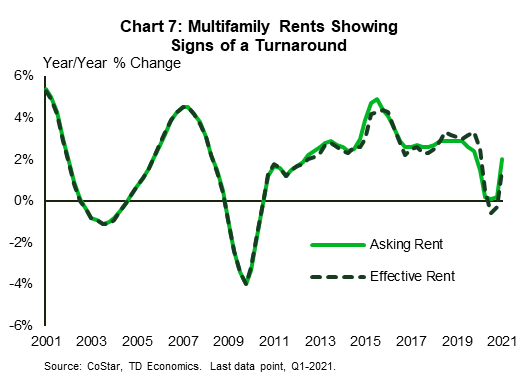

Improved demand helped nudge the vacancy rate slightly lower at the start of this year. Meanwhile, rent growth also appears to show signs of a turnaround (Chart 7). That said, the use of concessions to help lure in tenants remains widespread. In fact, despite easing somewhat in popularity in the past four months, the use of concessions is particularly prevalent in downtown areas, where an estimated one in two properties still offer some discount, compared to only 20% in the suburbs. Intuitively, the most-affected areas continue to offer the most perks. The Bay Area is a prime example, with many high-end properties there offering a combination of concessions, such as one or more months of free rent, complimentary parking, gym memberships, fitness equipment, free cable and internet, several hundred dollars of move-in credits or donations to local charity etc.

With vaccinations continuing at a healthy pace of over 2.4 million per day on average, the abating health crisis bodes well for multifamily demand moving forward. The path toward normalcy will bring about stronger economic growth this year and will facilitate the recovery of more jobs, including in badly-bruised urban areas. An improved employment backdrop should help young adults move out of their parents’ homes. Meanwhile, stronger overall confidence will allow some workers to return to the office and should channel more spending toward the leisure and hospitality industry, supporting the sector’s employment recovery. As more and more cultural, entertainment and gastronomical institutions (i.e. bars, restaurants, concert venues etc.) turn on the lights, the allure of dense multifamily living should begin to shine brighter once again.

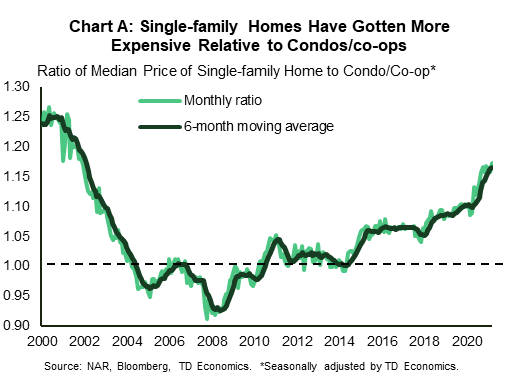

Given population shifts away from urban cores and into the suburbs, the availability of apartment units in the suburbs is shrinking. Along with the still-generous concessions offered in urban cores, this is an added factor that has helped tilt demand back toward downtowns recently, where more seasonal demand patterns have emerged. At the same time, record-low for-sale inventories of single-family homes, affordability challenges as a result of strong price growth (single-family homes have become more expensive vis-à-vis condos/co-ops, see Chart A in the appendix) and rising interest rates are hurdles to homeownership for those on the lower income scale. This means that limited choice elsewhere should help tilt some demand back toward dense urban living where the availability of rental units remains more abundant. The fact that developers are adding a bit more space to one-bedroom units, should be an added small incentive in favor of denser apartment living in a post-pandemic world as Americans continue to work remotely at an increased capacity.4

Supply Should Cool with Time

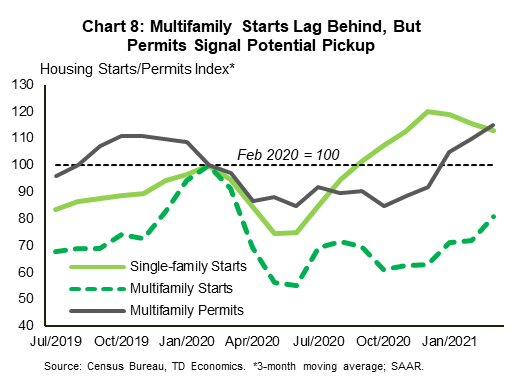

With Americans spending more time living and working at home during the pandemic, the race for space that ensued soon after the onset of the pandemic swayed homebuilding activity heavily toward single-family homes. New multifamily construction, meanwhile, fell sharply and remains well below its pre-pandemic peak (Chart 8). The pullback in new projects has thinned the multifamily construction pipeline. The number of multifamily units currently under construction has fallen to an estimated 580k thousand – still lofty, but well below the 700 thousand pre-pandemic peak recorded at the start of last year.

The completion of multifamily units varies by the size of the project, but, on average, it takes about a year-and-a-half from start to finish.5 Based on development timelines and the current construction pipeline, the level of supply that will hit the market in the next few months is expected to remain elevated by historical standards. This is an important element that’s likely to nudge the vacancy rate higher this year.

Structural Headwinds to Hold Back Pace of Recovery

Despite an improving economic outlook, the multifamily market will continue to face several headwinds, which will limit the sector’s scale and speed of recovery. The pandemic has shone a light on (and has helped expand) the capacity of the U.S. labor force to work from home. Despite easing in recent months, more than a fifth of the U.S. workforce continue to tele-work (see here).

While many Americans will indeed return to their traditional office as the health crisis subsides, a significant share of the workforce will continue to work remotely at an increased capacity. This narrative is supported by the fact that many firms have already invested heavily in remote working technologies and infrastructure. With many of these investments being sunk costs, there will be an incentive to continue utilizing them, especially in a post-recession environment where firms will be looking to control expenses (i.e. office space costs).

In similar fashion to the rise in remote work, remote learning for older students is also likely here to stay at an increased capacity relative to the pre-pandemic period. Changing preferences and investments in technology are likely to limit the comeback of students to college campuses. What’s more, a growing number of colleges and universities are requiring students to get vaccinated against COVID-19 to attend in -person classes this fall (see here). While this could certainly help expedite the path toward normalcy, it could also push some students toward online learning (i.e. those that are unwilling to get vaccinated). Given the many variables at play, the degree of the impact remains uncertain. But, overall, this trend is likely to limit the support for markets that cater to student housing in the near-to-medium term.

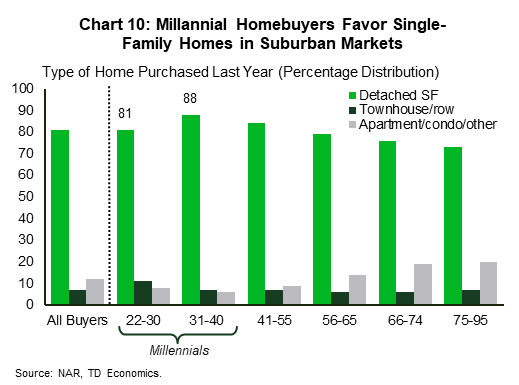

Another important headwind for multifamily housing is the country’s changing demographic backdrop, which is likely to increasingly favor less denser living. After years of sitting on the sidelines, millennials are making the leap into homeownership. Millennials were an important source of resilience for homeownership demand in the early stages of the pandemic (see our report here) and made up the largest share of homebuyers at 37% last year (see here). The type of home purchased by this age group were predominantly detached single-family homes at 81% for younger millennials (22-30) and 88% for older millennials (31-40), with most located in suburbs (Chart 10). This trend is likely to continue as millennials grow older and increasingly enter the family-forming stage, benefitting the single-family market and likely acting as a headwind for the rental market.

Stronger Immigration Can Help Ease Pressures from Structural Headwinds

Immigration fell steeply last year – an important factor behind the deceleration of population growth to just 0.35%. The steep slowdown in immigration is related to the pandemic, which reduced travel worldwide. But, a more restrictive take on immigration from the past U.S. administration likely also played a role. Net international migration fell from over a million in 2016 to under 600 thousand in 2019 (note that Census immigration estimates for 2020 are not yet available; see Chart 11). That said, both of these factors are turning the page. Indeed, with the pandemic subsiding as a result of increased inoculations, mobility and travel should tread toward more normal patterns. Meanwhile, friendlier immigration policy from the new administration can also lend a hand.

In a typical year, where changes in immigration inflows may not vary drastically, the effect that this channel has on the multifamily market is fairly limited. However, given a very low starting base, the return of immigration inflows to more normal levels can have a more pronounced positive impact this time around. For example, if net migration, which likely came in well below half a million last year, trends toward one million – similar to the levels seen in Obama’s last years in office – the addition of several hundred thousand more individuals per year over the medium term, can help prop up demand for multifamily housing. While foreign-born residents that have lived in the country for a long time tend to have similar homeownership levels to the broader U.S. population, recently arrived immigrants largely rent. For instance, the 2010-2018 immigrant cohort skews heavily toward rentership, with over three quarters of the units they occupy classified as renter-occupied.6 Large metropolitan areas — such as New York, Los Angeles, Miami, along with Dallas, Houston, Chicago, San Francisco and Boston — which tend to have a strong gravitational pull on new immigrants, would likely see the biggest benefit from an increase in immigration levels.7

Bottom Line

The pandemic dealt a heavy blow to the U.S. multifamily market, even as this was not the most affected corner of commercial real estate. The dispersion of pain varied widely by market and sub-segment. Large urban and coastal multifamily markets generally fared worst. Meanwhile, suburban multifamily markets generally fared better, with some even benefiting from the pandemic given an inflow of residents.

While some weak spots remain, the multifamily market has been showing signs of stabilization, with demand at the national level improving in recent months and rent growth showing early signs of a turnaround. Strong economic and job growth will remain supportive to multifamily demand in the quarters ahead. Meanwhile, improved confidence and a gradual return of workers to the office will also lend a hand. But, with the delivery of new multifamily units expected to continue to come in at a high level over the next few months, the vacancy rate has more room to rise in the near-term. The delivery of new units is expected to cool with time, which will help ease supply-sided pressures on vacancies and rents.

Despite an improving outlook for the multifamily market later this year and 2022 as the pandemic’s grip on the economy dissipates further and supply cools, structural headwinds related to the country’s changing demographic profile and the lingering popularity of remote work, are likely to limit the support for the multifamily sector in the years ahead. A return of immigration to more normal (i.e. higher) levels, can help mitigate some of the pressures from these structural headwinds.

Appendix

End Notes

- “The Great American Move Accelerates”, October 2020, https://www.realestateconsulting.com/the-light-great-american-move-accelerates/ U-Haul 2020 Migration Trends, January 2021, https://www.uhaul.com/Articles/About/22745/2020-Migration-Trends-U-Haul-Names-Top-25-Us-Growth-Cities/

- 2021 JA Teens & Personal Finance Survey, https://jausa.ja.org/local-repository/2021-ja-teens-and-personal-finance-survey

- As per data from Apartments.com and CoStar.

- CoStar, December 2020, https://www.costar.com/article/1706253319/costar-predicts-bigger-apartments

- Multifamily units in 2019 took on average 15 months from start to completion, with smaller buildings of 2-4 units taking 13 months and those with 20 or more units taking 17 months.

- CBRE, June 2020, https://www.cbre.com/investor-hub/declining-immigration-a-small-drag-on-rental-demand?article=6d885963-3dc9-4edb-a735-d7e9bfc51d34&feedid=bbc4df08-52a9-40f7-8c05-a316cc1cb8d7

- bid.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: