Hurry Up & Wait:

Congressional Fiscal Priorities in the First 100 Days

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: February 21, 2025

- Category:

- U.S.

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- Congressional Republicans have begun the process of implementing the President’s fiscal agenda via the budget reconciliation process – a legislative measure that circumvents the filibuster rule in the Senate and only requires a simple majority to pass.

- The total cost of proposed tax cuts is estimated to be about $8-9 trillion, assuming the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) is permanently extended. Given the House Republicans’ reconciliation bill only accounts for $4.5 trillion in tax cuts, it is likely they are aiming for a temporary extension of the TCJA.

- In its current form, the House bill would be expected to boost average annual real GDP growth by up to 0.2 percentage-points over the coming decade, but also add $2-3 trillion to the federal budget deficit. However, reconciliation bills are not permitted to increase the fiscal deficit beyond the ten-year horizon, meaning that House Republicans will need to reconcile this disparity prior to its passage.

- At the same time, Congress is also contending with the March 14th expiration of the continuing resolution currently funding the federal government and the prospect of the U.S. Treasury running out of funds by mid-summer due to the debt ceiling.

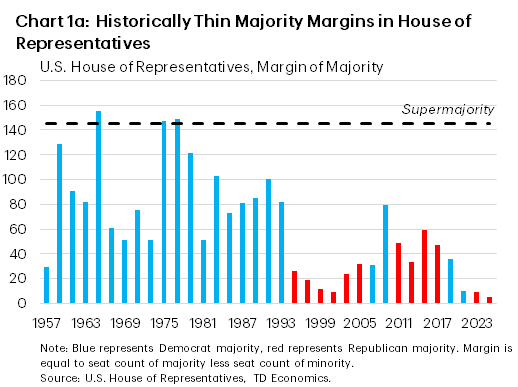

The 119th session of Congress is halfway through its first 100 days with a multitude of goals they want to, and in some cases need to, achieve within the coming months. However, razor thin margins of majority have complicated the ability of the Republican trifecta in the House of Representatives, Senate, and White House to implement the legislative priorities of the new federal government.

Assuming the Republicans’ proposed multi-trillion-dollar tax and spending cut package is eventually passed by Congress, it could add up to 0.2% to average annual real GDP growth over the coming ten years but would also likely add $2-3 trillion to the fiscal deficit over that time period.

In addition to this massive legislative package, Congress is also contending with two other deadlines it is simultaneously trying to meet. The first is related to funding for the federal government, with the risk of a government shutdown occurring once the current continuing resolution expires on March 14th. Then, roughly four to five months after that deadline, the federal government may be put at risk of defaulting on its fiscal obligations if the debt limit is not raised or suspended. Suffice it to say, the first branch of the federal government has no shortage of work to get done in the coming months.

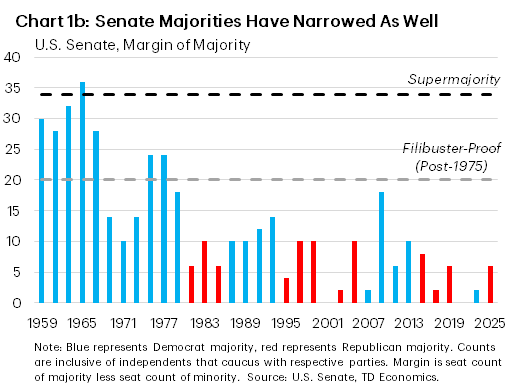

The President’s Fiscal Priorities Meet Congress

The highest priority for Congressional Republicans right now is passing the legislative agenda of President Trump. Theoretically, the quickest way to do this is through a budget reconciliation bill, which cannot be filibustered in the Senate and thus only requires a simple majority to pass. This has been a valuable tool for both parties in recent decades, as a filibuster-proof majority has not existed in the Senate for nearly half a century. The progressively narrowing margins of majority in each chamber of Congress over the past few decades (Chart 1a & 1b) has enhanced the challenge of passing significant legislation, even by way of the budget reconciliation process. The House is acutely encumbered by this constraint at the moment, as two resignations have dwindled the Republican four-seat majority down to two seats, with the prospect of a third resignation in the coming weeks. If this occurs, it will only take one dissenting vote to derail this legislation if the vote were to fall along party lines. With special elections for the vacated seats still over a month away, navigating the legislative process in the lower chamber of Congress is expected to remain challenging for the foreseeable future.

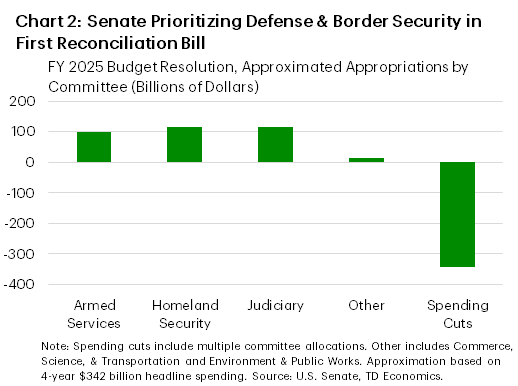

In cognizance of these temporary constraints in the House, Senate Republicans have aimed to implement a two-bill approach to the reconciliation package which would push the vote for the more contentious tax and spending cuts to later this year. The Senate’s first bill incorporates over $300 billion in appropriations for defense and border security expenditures – two of the higher priorities of the executive branch. These expenditures, implemented over the next four years, would be fully offset by spending cuts (Chart 2).

The second reconciliation bill, which has not been released by Senate Republicans yet, would likely be 20-25 times larger and inclusive of the tax cuts proposed by President Trump. These would include extending the tax cuts included in the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (which will otherwise expire at the end of this year), eliminating taxes on social security, tips, and overtime income, and cutting the corporate tax rate for domestic manufacturers. According to the Center for a Responsible Federal Budget, the central estimate for the total cost of these tax cuts is estimated to be in the range of $8-9 trillion dollars over the next ten years1, dwarfing the roughly $5 trillion spent on fiscal stimulus during the pandemic.

While this would be an enormous addition to the deficit, there are additional caveats to keep in mind. The first is that the largest tax cut, related to extending the 2017 TCJA, could be extended for less than the ten-year horizon for which the deficit impact of reconciliation bills is assessed. Framing is important here, as reconciliation bills are not permitted to raise the deficit beyond a ten-year horizon. So why is this relevant in the current context? Primarily owing to the fact that the House Budget Committee, which is currently pursuing a single reconciliation bill approach (that has been backed by the President), has outlined no more than $4.5 trillion of tax cuts for the House Ways & Means Committee – the tax committee - in their bill. Now, this is simply the headline allocation, meaning the Ways & Means Committee could implement spending cuts to offset the difference but it would likely be challenging to fully reconcile the differences without setting a shorter horizon on extending the 2017 TCJA. As a sidenote, the Senate Republican leadership sent a letter to President Trump, House Speaker Mike Johnson, and House Ways & Means Chairman Jason Smith, emphasizing that they would not support a tax package that did not permanently extend the 2017 TCJA tax cuts2.

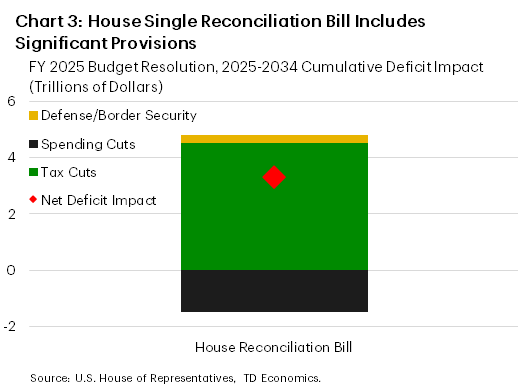

To partially offset the $4.5 trillion in tax cuts, the House Budget Committee outlined at least $1.5 trillion in spending cuts (Chart 3). Nearly all of the outlined spending cuts were to come from the Energy & Commerce, Education & Workforce, and Agriculture Committees. Options being considered by these committees include rolling back provisions from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, Medicaid cuts, Medicaid work requirements, reducing the borrowing limit on student loans, mandating states pay a higher share of SNAP benefits (food stamps), and expanding SNAP work requirements. In total, the House Budget Committee is aiming to cut mandatory spending by $2 trillion over the next ten years.

However, this still leaves a $2.5 trillion gap between the proposed tax cuts and the proposed spending cuts. If this gap cannot be reconciled, then the reconciliation bill specifies that it would be deducted by the House Ways & Means Committee appropriations, essentially meaning the tax cuts would be brought down to the level of spending cuts.

The economic impact of the legislation could also be used to raise the projected tax revenues which would result from the bill’s provisions under a dynamic assessment but closing a $2.5-3 trillion gap would still be a herculean feat. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated that closing a $3 trillion gap over the span of ten years would require average annual real economic growth of 3.2%3. This would significantly deviate from current baseline estimates used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) – which assume the 2017 TCJA provisions expire – of 1.8%. Therefore, the House would be making an implicit assumption that this bill will push average annual real GDP growth higher by over 1 percentage-point over the next decade.

There have been multiple studies completed on the economic impact of fully extending the 2017 TCJA – the largest tax cut included in the reconciliation bill. The two primary studies include one by the CBO4 and another by the Joint Committee on Taxation5. The former found that the extension had a negligible impact on real GDP growth over the 10-year horizon, due primarily to a crowding out effect on business investment from the higher deficits (i.e., private sector capital expenditures are reduced by the need to finance the federal deficit). Given that the share of outstanding U.S. Treasuries held by domestic investors is near an all-time high (see here), this would be a saliant point to bear in mind when considering the deficit impact of this legislation. The Joint Committee on Taxation’s analysis found that the extension cumulatively increased real GDP by 0.2-0.7% over the 10-year horizon. However, in average annual terms this would net out to a roughly negligible impact on aggregate.

This leaves the net new tax changes to contend with the partial fiscal drag that would result from the proposed spending cuts. Our estimate for the 10-year aggregate economic impact of the net new tax cuts is 2.4 percentage points (ppts) above our baseline. While this would be a positive development, the actual impact would likely be less due to the accompanying spending cuts in the bill. Taken altogether, the House reconciliation bill could add up to 0.2ppts to average annual economic growth over the coming decade. This would be less than the more than 1ppt needed to close the $2.5-3 trillion gap between proposed tax and spending cuts, meaning Congress will need to reconcile this divergence further to avoid increasing the deficit over the long run.

Tariff revenues have been proposed as a potential partial offset to the tax cut proposals, but this would require several assumptions to be made about their longevity and the dynamic effect they have on the economy. If the U.S. effective tariff rate were to increase from its current level of 3% to 7.5%, it would be expected to generate $100 billion in additional revenues in 2025, but fall in subsequent years as firms adapt. Over the long run, if tariffs are left in place, they could stimulate domestic production resulting in higher tax revenues, but there is no guarantee they would offset the negative near-term effect of the tariffs or firm adjustment costs in the medium-term.

Congress may also be tempted to incorporate the spending cuts being implemented by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), but measures announced to date, such as reducing the size of the federal workforce, are unlikely to move the needle in a multi-trillion-dollar bill. As the power of the purse rests with Congress, the heavy lifting of balancing a tax cut bill will rest with the legislature.

The bottom line is that Congress must implement a legislative package that does not increase the federal budget deficit beyond the ten-year window – a task that will largely rely on matching tax cuts to spending cuts. Congress currently has time on their side to achieve this, but the looming expiration of the 2017 TCJA will add impetus to the negotiations if they do not progress in the months ahead.

Back-Burner Issues to Keep an Eye On

While Congress’ attention has been focused on reconciliation bills, and confirming cabinet nominees in the Senate’s case, the expiration of the continuing resolution currently funding the federal government has begun to sneak up on the horizon. Congress has roughly three weeks to pass the twelve appropriation bills for the fiscal year 2025 budget or, more likely, another continuing resolution. The House passed five of the appropriation bills last summer, but the Senate has not passed any yet. With the Republican party now in control of both chambers of Congress, this should be a theoretically straight-forward process, but past experiences with the reconciliation process may herald difficulties ahead. For reference, the budget for fiscal year 2017 was not passed until May 2017 – more than 3 months after President Trump assumed office for the first time with a stronger Republican majority in Congress.

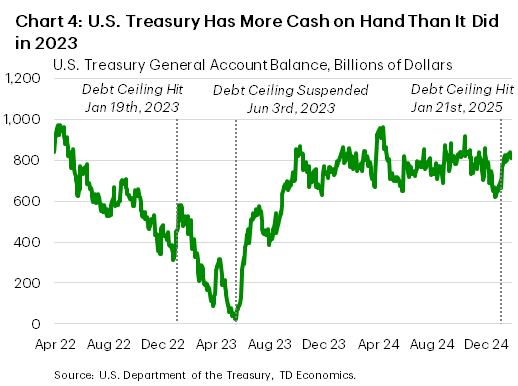

Further down the line, the U.S. Treasury will be staring down a potential technical default if the currently binding debt limit is not raised or suspended by Congress. The debt limit was hit on January 21st, and the Treasury has since been implementing extraordinary measures to manage its fiscal obligations. However, these measures can only last so long, with the date that funds run out referred to as the X-date. Expectations are for a mid-late summer X-date, in part owing to the higher cash balance that the Treasury had on hand at the time the limit was hit (Chart 4).

Congress has taken some preliminary actions to address this deadline, with the House reconciliation bill including a $4 trillion increase to the debt limit. Based on the current trajectory of fiscal debt, this would likely last less than 2 years.

In recent years, Congress has tended to wait to address budget and debt limit deadlines until the final weeks before they are hit. Less than two years ago, the eleventh-hour resolution of a debt ceiling deadline resulted in a credit rating downgrade from Fitch – nearly twelve years to the day that S&P did the same. While the existence of a trifecta in Congress and the White House should prevent this from happening a third time, the thin majorities that exist in the former will likely keep financial markets apprehensive until the deadline is met.

Bottom Line

Historically, sweeping both chambers of Congress and the White House would permit a party to easily implement its legislative priorities. However, the progressively thinning margins of majority in Congress have worn out this truism in recent years, with Congressional leadership now required to achieve near universal consensus within their party to pass major legislation. This has mired the reconciliation process for Republicans in 2025, with the magnitude of the President’s proposed tax cuts also adding to the challenge. Ultimately, Congressional Republicans will need to adopt a unified approach to legislating the President’s agenda while remaining cognizant of the upcoming budget and debt ceiling deadlines.

End Notes

- "Trump Tax Priorities Total $5 to $11 Trillion", Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

- Senate Republicans Letter to President Opposing Short-Term Tax Package

- “$3 Trillion of Dynamic Feedback is Fantasy Math”, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

- “How the Expiring Individual Income Tax Provisions in the 2017 Tax Act Affect CBO’s Economic Forecast”, CBO.

- “JCT Methodology For Analyzing Macroeconomic Effects 2024”, JCT.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: