U.S. Treasury Market Uncertainties: Higher Supply and Shifting Demand

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: November 19, 2024

- Category:

- U.S.

- Financial Markets

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- Higher structural deficits are expected to push U.S. federal government debt as a share of GDP to 100% next year and 122% by 2034. This translates to a roughly $22 trillion (or 85%) increase in the supply of U.S. Treasuries between 2024 and 2034.

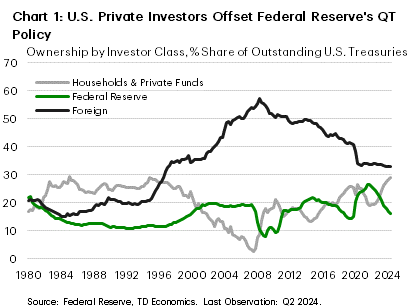

- Higher debt issuance was easily digested by financial markets in 2020-2021 as the Federal Reserve engaged in quantitative easing. However, the shift to quantitative tightening has increased the burden on domestic investors as foreign investors have been unwilling to replace the lost demand from the Fed.

- As a result, price sensitive investors, namely U.S. private funds, are now close to replacing foreign investors as the largest investor in Treasuries.

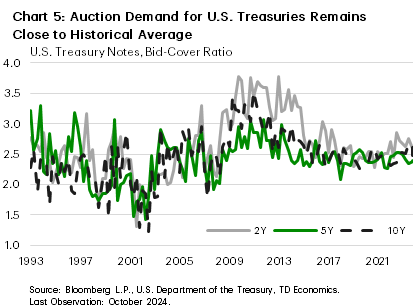

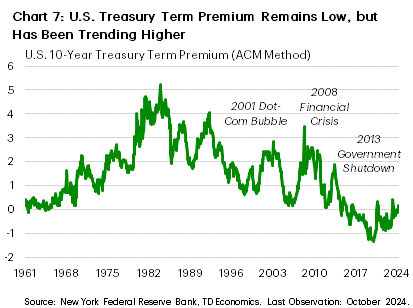

- Demand at U.S. Treasury auctions has remained stable, but the term premium has risen to its highest level in a decade, indicating that investors are demanding higher compensation for holding U.S. Treasuries.

- The reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar is expected to remain supportive of U.S. Treasury demand, but higher deficits and higher buyer price sensitivity could lead to higher volatility and higher interest rates over the longer-term.

The cumulative federal deficit between 2020-2023 was $9 trillion – equal to nearly 40% of the value of all outstanding marketable U.S. Treasuries as of the second quarter of 2024. This resulted in a significant increase in the supply of U.S. Treasuries which had to be absorbed by financial markets. The Federal Reserve, through its implementation of quantitative easing (QE), largely mitigated the risk this presented in the first two years of the post-pandemic period (2020-2021). However, as the Federal Reserve has reduced its holdings through quantitative tightening (QT), and foreign investors have lowered their appetite for Treasuries on aggregate, domestic investors have had to step up to replace the lost demand.

This mix of ever-expanding Treasury supply and more concentrated demand within the U.S. domestic market poses a growing risk to the U.S. Treasury market. At the very least, it implies more frequent bouts of turbulence and a higher sustained risk premium, especially as investors navigate the uncertain U.S. policy landscape in the coming months.

U.S. Treasury Demand, Same Name Different Faces

The U.S. Treasury market stood at $26 trillion in August 2024 – 51% larger than it was in December 2019. The bulk of this uptick in issuance came in the first two years of the pandemic, of which the Federal Reserve absorbed roughly 60%. Through its quantitative easing policy, the Federal Reserve was able to head off the risks related to a roughly $6 trillion dollar (or 35%) increase in outstanding government debt between 2020-2021.

Moving into 2022, with inflation beginning to rise above the Federal Reserve’s target, the central bank began to tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates and reducing its holdings of U.S. Treasuries. It accomplished the latter by ending its purchases of Treasuries and allowing its existing holdings to roll off its balance sheet. Even though this was done gradually, the reduction in the Federal Reserve’s purchases in the Treasury market at a time when issuance was continuing to rise had considerable implications.

The initial hand-off in 2022 was unproblematic, as the economy continued to recover from the pandemic and ample liquidity was available to be channeled towards U.S. Treasuries. Between the fourth quarter of 2021 and the second quarter of 2024, the household & private fund share of U.S. Treasury holdings rose from 19.2% to 28.9% (Chart 1). This not only reversed the displacement created by the Federal Reserve’s QE policy in the prior two years, but also pushed the household & private fund share to a level that it had only reached briefly before in the mid-1980’s and mid-1990’s. One reason why this trend emerged was due to an increase in domestic hedge fund exposure to the U.S. Treasury market via carry trades, an investment practice whereby funds borrow in low interest rate currencies and invest in higher interest rate currencies (i.e borrow Japanese Yen, invest in USD assets).

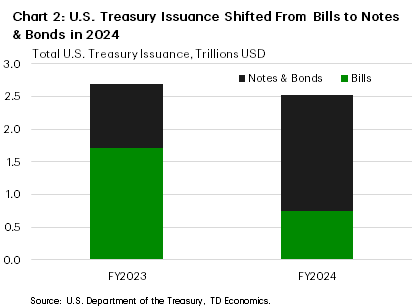

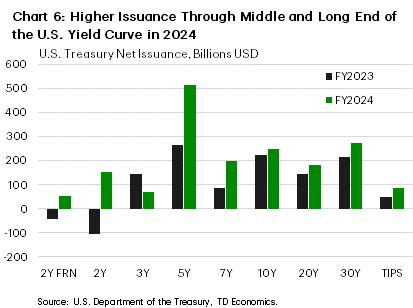

Moving into 2023, the U.S. Department of the Treasury also shifted its issuance towards shorter-term bills (Chart 2). This was primarily driven by the rapid rise in interest rates at the time, as the government sought to manage its exposure to high-yielding long-term debt, in addition to a need to rebalance their issuance to a more normal distribution. The shift in issuance saw money market mutual funds (MMF) ramp up their purchases of U.S. Treasuries. However, moving into 2024, the holdings share of MMFs have fallen slightly as issuance shifted back towards long-term notes.

Cumulatively, these trends have increased the reliance of the Department of the U.S. Treasury on private domestic investors, with this group close to becoming the largest holder of U.S. Treasuries for the first time since 1996. This is an important development, as this group has typically been more sensitive to price changes, which means their higher share of the market could lead to higher volatility.

Furthermore, this shift in the composition of demand appears to be structural. When the Federal Reserve ends its QT policy in the coming months, it’s holdings will equal roughly 15% which is close to where it sat prior to the pandemic. Absent a new economic shock, the use of the Fed’s balance sheet for extraordinary policy will end and its holdings as a share of the total market will be kept roughly constant. This means that the domestic private sector will need to remain a primary buyer of U.S. Treasuries going forward.

In addition, the developments in foreign investor demand for U.S. Treasuries over the past four years have been curious. Since the start of the pandemic and the Fed’s QE policy, foreign investors have kept their share of the U.S. Treasury market constant around one third. This is down from the 41% share they held in 2019, but it is in line with the post-2008 trend, which saw the foreign investor share of the market fall consistently in the decade leading up to the pandemic.

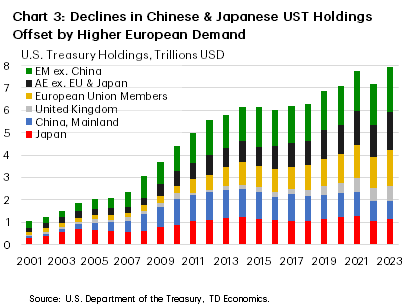

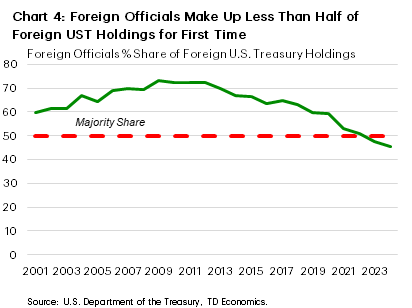

Looking under the hood, the decline since 2008 has primarily been driven by falling demand among the two largest holders of U.S. Treasuries: Japan and China (Chart 3). A partial offset was provided by rising demand in the E.U., the U.K., and other advanced economies, but more recently demand from these countries has accelerated to become a full offset and keep the foreign investor share of the Treasury market constant since 2020. While greater diversity among foreign investors is likely a positive development, it has primarily been driven by private investors (Chart 4). If this is considered in conjunction with the rising share of the market among domestic households & private funds, then the U.S. Treasury market’s exposure to price sensitive buyers is likely currently at an all-time high.

Current U.S. Treasury Market Functioning & Implications for the Future

The U.S. Treasury market has seen notable developments over the past four years, both in response to the onset of the pandemic and the inflation spike seen thereafter. The accompanying compositional changes to the market have not yet had a significant impact on its functionality, with higher issuance and the Federal Reserve’s QT policy being digested by financial markets without major issue.

This has been evidenced by the bid-cover ratio (Chart 5) which measures the amount of bids received relative to the amount sold in U.S. Treasury auctions. Demand has remained roughly 2.5 times supply in the 2-, 5-, and 10-year note auctions, which is roughly consistent with the pre-pandemic trend. This was maintained in 2024 despite a higher issuance in all three of these tenors, particularly in the 5-year term (Chart 6). This suggests that market demand has been able to keep up with the higher pace of issuance seen to date.

Although this represents a positive development, other metrics have shown some signs of strain. The U.S. Treasury term premium, which measures the compensation investors demand for holding longer-term debt, has risen to its highest sustained level in nearly a decade (Chart 7). From a historical perspective, this rise appears somewhat insignificant relative to the levels seen during the 1980’s and past crises, but it does show that investors are beginning to require higher levels of compensation to hold U.S. Treasuries. While this is not solely related to the higher levels of debt issuance, as political and economic risks are also captured by this metric, it is likely that the higher supply of U.S. Treasuries is playing a part in the recent uptick.

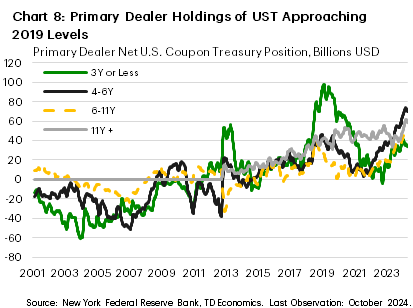

In addition to the rising term premium, we have also seen some developments of late which merit attention. This includes the net U.S. Treasury holdings of primary dealers - large financial firms which agree to purchase U.S. Treasuries at every auction (Chart 8). Higher issuance has led to higher volumes being warehoused by primary dealers, which could limit their ability to perform their function of backstopping auctions and intermediating the secondary market.

In recognition of this risk, the Department of the U.S. Treasury began buying back U.S. Treasuries in May of this year, with the intention of stabilizing markets, for the first time in more than two decades. At present, the Department of the U.S. Treasury is implementing both cash management buybacks (intended to reduce supply volatility at the short end of the curve) and liquidity support buybacks (across the curve). However, the size of buybacks to date and their impact on the market has remained relatively limited overall. The scheduling of the cash management buybacks - which began in September -around major tax payment deadlines shows that fiscal authorities are intent on smoothing issuance around dates of potential outsized liquidity withdrawals.

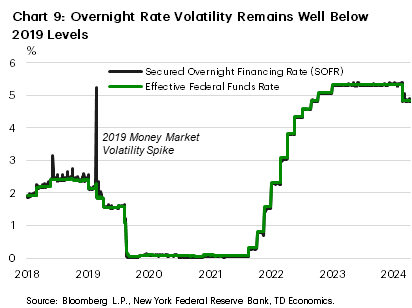

The last time that primary dealer balance sheets were elevated to this degree, an outsized withdrawal of liquidity from the market related to a corporate tax deadline resulted in a spike in market volatility that required a Federal Reserve intervention to be stabilized (Chart 9). While the prospect of a potential recurrence of this event is concerning, current volatility in the overnight market has remained well below 2019 levels. Nevertheless, it warrants reminding that rising U.S. Treasury issuance and elevated primary dealer balance sheets acted as an accelerant in 2019, not as a catalyst. Combined with a shift in U.S. Treasury holdings towards more price-sensitive buyers, these developments could lead to sharper reactions to future catalysts that may necessitate a Federal Reserve intervention like that seen in 2019. This underlies the rationale for the Department of the U.S. Treasury to take stabilizing action as it is currently doing, albeit to a limited degree. The efficacy of these measures is thus still an open question, but their use for the first time since 2001 is likely indicative of market concerns regarding the growing supply of U.S. Treasuries.

While the end of the Federal Reserve’s QT policy in the coming months will likely provide some relief to the market, the U.S. Treasury market is still expected to grow by roughly $2 trillion per year over the next 5 years – only slightly below the average of the prior five years which included a global pandemic. There are also additional upside risks related to the proposed policies of the incoming administration which could lead to higher deficits and an accelerated pace of growth in the supply of U.S. Treasuries. Market interventions such as that seen by the Federal Reserve in 2019, and the Department of the U.S. Treasury today, may become more common to contain potential bouts of turbulence with the price sensitivity of the demand base now higher.

Bottom Line

The U.S. national debt is expected to exceed the nation’s GDP next year and continue to rise on the back of higher structural deficits over the coming decade. The resultant increase in the supply of U.S. Treasuries has thus far been absorbed by financial markets without major issue, but the rising term premium, in addition to the need for the Department of the Treasury to implement buybacks to offset pressure on primary dealers, has indicated some signs of minor strain. Over the longer-term, the shift in ownership of outstanding debt towards more price sensitive buyers, both domestically and abroad, may also lead to higher structural volatility moving forward. Material sustained market dislocations are unlikely to occur, as interventions by the Federal Reserve would be used to stabilize markets, but if this becomes a more frequent occurrence then it would likely lead to a higher term premium and structurally higher interest rates over the long-run.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: