Shifting Sands:

U.S. Inflation’s Changing Dynamics

Rannella Billy-Ochieng’, Senior Economist | 416-350-0017

Brett Saldarelli, Economist | 416-542-0072

Date Published: June 26, 2023

- Category:

- US

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Inflation climbed to a 40-year high last year as strong demand for goods overwhelmed global supply-chains. Goods prices have slowed since then, but services are now playing a leading role in driving inflation.

- A surge in corporate profits during the pandemic and its immediate aftermath raised concerns that increased profit margins were driving inflation higher.

- Looking through a historic lens, the rise in profits was not abnormal. Corporate profits typically rise in the early stages of economic recovery, coinciding with sluggish wage growth as the job market takes longer to recover from the downturn.

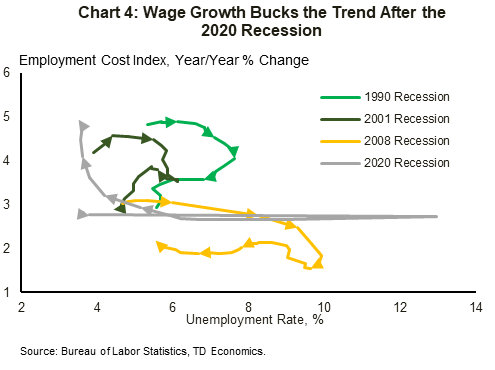

- The labor market recovery from the pandemic has been relatively fast, helping to fuel the strongest wage growth since the 1990s.

- High inflation is a symptom of an economy bursting at the seams. As demand slows, profit and wage growth are likely to follow, bringing inflation lower with them.

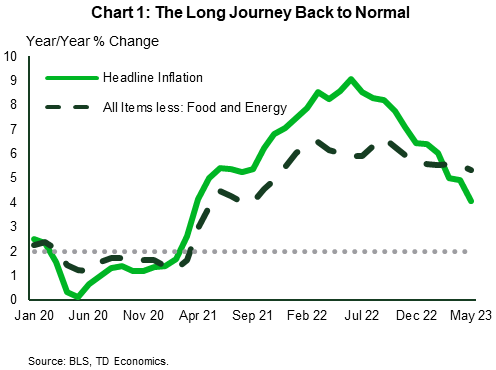

The bitter taste of high inflation continues to linger two years after its liftoff in the aftermath of the pandemic. U.S. inflation hit a peak of 9.1% year-over-year in June 2022.1 While it has moved steadily lower since then — reaching 4.1% in May of this year (Chart 1) — it is still well above its pre-pandemic rate and the Fed’s 2% target.

The drivers of inflation have shifted over time. In the early stages, supply chain dislocations and an abrupt change in spending patterns toward goods and away from services led to accelerated price growth. This early period was also marked by a widening in corporate profit margins, leading to charges that surging profits were responsible for the rise in prices. Since then, profit margins have narrowed and the sources of inflation have shifted from goods to more labor-intensive services. Wage growth now accounts for a significant share of the rise in prices.

The pattern of corporate profits rising in the early stages of an economic recovery is not unique to this economic cycle, but something that has occurred consistently over history. Businesses raise prices early in the economic cycle in response to strong demand and anticipation of higher costs. As those higher costs come to fruition, profit margins narrow.

Elevated wage and profit growth are symptoms of an economy in which demand exceeds supply. As demand slows and the economy cools, price pressures will follow.

Elevated Corporate Profits During Pandemic Prompted Scrutiny

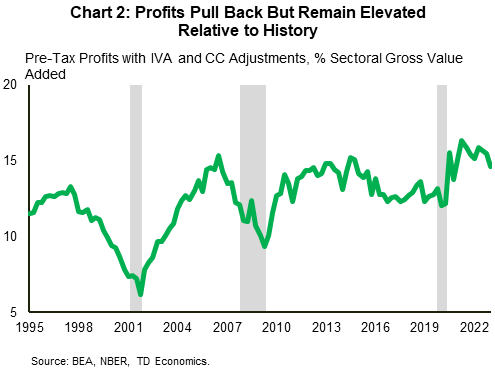

Corporate profits soared to a multi decade high during the pandemic (Chart 2), prompting charges that corporations were taking advantage of the crisis to pad their margins. According to one theory, the universal nature of the pandemic made it easier to coordinate price increases.2 If a business believes that their competitors are also raising prices, the cost of doing so in terms of lost market share is diminished.

In fact, there is nothing particularly unique about this current cycle versus past economic cycles. Profit margins typically increase in the early stages of recoveries as forward-looking businesses raise prices in anticipation of rising costs. These actions serve to temporarily boost margins and prices. As cost pressures materialize, margins evaporate back to normal levels.3

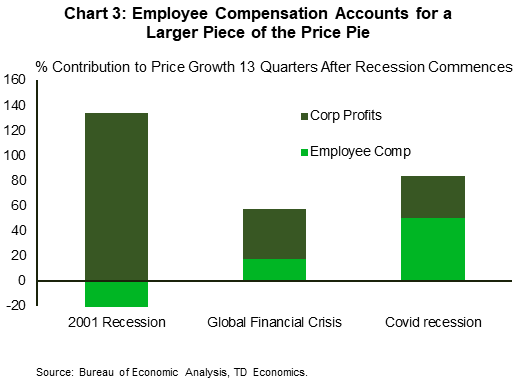

Notably, unit profits (profits per unit of output) have accounted for a smaller share of price pressures during this recovery period than in the past (Chart 3). Taken over a longer-period, corporate profits are not the main force stoking inflation pressures during the pandemic and post-pandemic era.

Undoubtedly, not all industries are the same. Retail trade profits expanded considerably in 2021 and have continued to outpace wage growth even recently.4

Tight Labor Market Has Tipped the Scales Back Toward Wages

In contrast to profits, wages are often slow to recover from downturns and tend to be less influential on price pressures in the initial stages of recovery (Chart 4). This occurred during the recessions in 2001 and 2008.

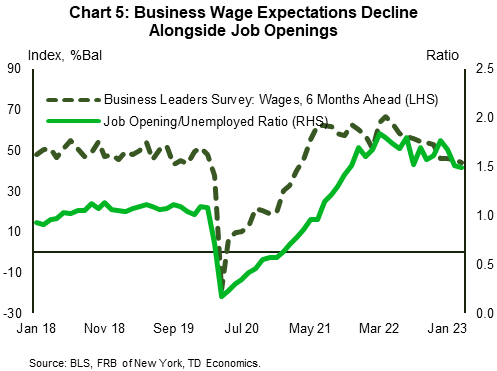

The post-pandemic recovery has shortened this typical lag. Faster wage growth has resulted in unit labor costs accounting for an increasingly larger share of price pressures. In the first quarter of 2023, labor costs accounted for half of the change in per unit prices. This is consistent with the dearth of available workers relative to demand, reflected in the ratio of job openings-to-unemployed persons reaching an all-time high in March 2022. Service-related industries, including leisure and hospitality, which boast one of the highest job opening rates, has experienced some of the highest wage increases.

There are early signs that labor market imbalances have started to recede. Job openings, while still elevated, have fallen from their record highs and business’ expectations of future wages are beginning to trend downward (Chart 5).

Shrinking Margins and Softer Wage Growth Will Help Fight Inflation

We expect economy-wide corporate profits relative to GDP to retreat from its peak of 12.1% in 2021 to 10.3% by the end of 2023. Industries that saw the highest margins (e.g., retail) may experience more margin compression as consumer demand fades alongside dwindling excess pandemic savings.

As firms contend with weaker sales, demand for workers is likely to slow. Softer wage and profit growth will help to bring down inflation. As those pieces fall into place, we expect inflation to slow to 2.1% by the end of 2024.

Bottom Line

With inflation capturing headlines over the past two years, some are pointing fingers at corporations. When compared to historical norms most corporations are acting in a typical forward-looking manner.

Where the current environment differs is the job market. As businesses rushed to keep up with demand, competition for workers has pushed up wages in many industries. Labor costs now account for an unusually large role in explaining inflation.

To be clear, workers are not the villains in the inflation story any more than corporations. Instead, the root issue is an economy running hot, with demand in excess of supply. As these move into balance, inflation is likely to follow.

End Notes

- As measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- https://www.elgaronline.com/view/journals/roke/11/2/article-p183.xml

- https://www.kansascityfed.org/research/economic-bulletin/corporate-profits-contributed-a-lot-to-inflation-in-2021-but-little-in-2022/

- Restoring Price Stability in an Uncertain Economic Environment, Speech by Lael Brainard Vice Chair, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20221010a.html

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: