Highlights

- There was much debate on whether pandemic-enhanced unemployment benefits were running interference with the speed of the labor market recovery. Early evidence shows that the states that ended the benefits prematurely have nudged more workers off the sidelines, but there has been no major difference in hiring patterns relative to those that left the benefits in place.

- In contrast, the reduced cashflow from the cutoff of benefits appears to have led to more cautious spending behavior among affected households, risking a counterproductive economic impact.

- Households are simultaneously being confronted with the sudden end to the eviction moratorium. While impacts will vary by state and region, this creates an additional hurdle for the consumer cycle in the near-term.

To help soften the pandemic's labor market and economic impact, several rounds of federal pandemic aid were used to boost unemployment benefits. These included the Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (or PUC), which lifted recipients' income by an additional $300 per week, the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC), which allowed workers to collect unemployment benefits for an extended period of time and the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which offered benefits to those who were otherwise ineligible to receive standard benefits, such self-employed workers, independent contractors and freelancers. These extra benefits were set to expire by Labor Day (September 6th). However, about half of U.S. states decided to end some or all before this deadline. Specifically, 25 states ended their participation in the PUC early, while an addition 21 out of these 25 states also withdrew early from the PEUC and the PUA, most doing so in late June and early July.

Proponents of an early end to the enhanced unemployment argued it would help nudge workers back into the labor force at a time when jobs appeared to be plentiful and employers were reporting difficulty in finding qualified workers. More time may need to elapse before teasing out a firmer impact, but so far, the evidence points to only a minimal influence on job growth. On the other hand, the risk of an early cessation of benefits is that it will damper consumer spending as individuals engage in precautionary behavior to curb spending and adjust to the drop in cashflow.

The Rate of Job Growth Isn’t Much Different Between the Dids and the Did Nots

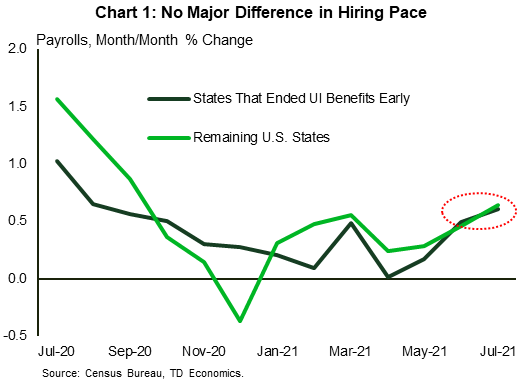

A quick snapshot comparison in employment growth between states that ended unemployment benefits early versus those that did not, reveals no major difference in payroll growth between the two groups (Chart 1). Early analyses that took a deeper dive into higher frequency and more detailed employment data also do not find strong evidence that an early end to enhanced unemployment benefits led to a significant boost in job growth. For example, an analysis from UMass Amherst finds that "there was no immediate boost to employment during the 2-3 weeks following the expiration of the pandemic UI benefits."1

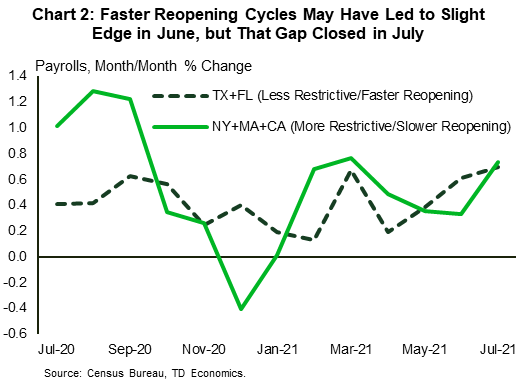

Performing the same comparison as above by using employment data from the household survey reveals only a slight edge for states that ended benefits early. However, given the myriad of factors at play, it is difficult to assert that any edge would be the direct result of an early end to benefits. Factors that can muddy the waters include changes in public health conditions (i.e. trends in COVID-19 cases and hospitalization) and differences in pandemic-related business restrictions. For example, many of the states that ended benefits prematurely, including the two large states of Texas and Florida, were also well ahead of their peers in easing or eliminating business capacity restrictions before the latest Delta-driven wave. This means that a slightly faster hiring clip in these states would already have been a natural expectation. We can test this notion by comparing large states that lie at the extremes. Texas and Florida reflect less restrictive states, while New York, Massachusetts and California are at the other end of the spectrum. The less restrictive group saw greater job growth in June, consistent with business conditions. However, by July, the gap between the two groups vanished as New York, Massachusetts and California eased their business restrictions and the employment engine kicked into higher gear (Chart 2).

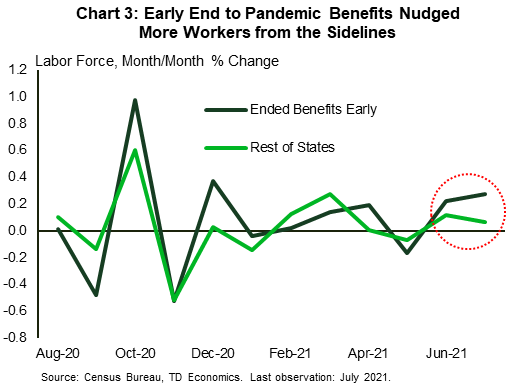

What seems to be more certain is the fact that those states that ended the enhanced benefits early saw a relatively more pronounced boost to their labor force (Chart 3). Putting the two pieces together, the strategy to end benefits early appears to have nudged more workers into the labor force, but so far this has not resulted in a significant boost to employment. This is perhaps occurring because it may take some time for those that have recently joined the labor force to find a job. Another recent UMass Amherst study offers additional insight into the matter. It finds evidence that the boost to the labor force and the resulting job gains from those that were previously unemployed are likely partially crowding out the ability of others, such as those that were not initially in the labor force (i.e. teens) to find jobs.

Did Consumer Spending Decline in States Where Benefits Ended Early?

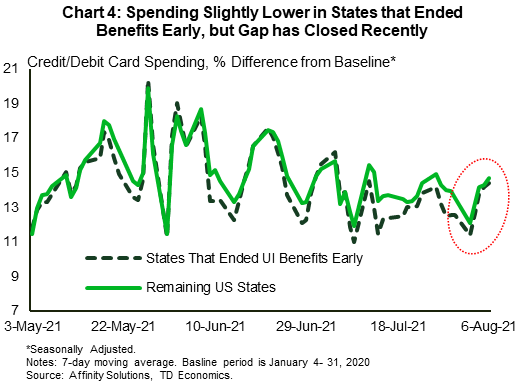

Removing pandemic benefits early would deprive recipients of a steady cashflow to which they may have become accustomed over the last several months. For individuals that cannot find a job quickly, this would likely mean that they would need to curb their spending to compensate for the reduced cashflow. A look at credit and debit card spending tracked by Affinity Solutions, points to an initial (though small) reduction in consumer spending for the states that ended benefits early. The gap between the two groups however has narrowed significantly since August (Chart 4). Focusing the lens on households at the bottom income quartile, who may be more affected by losing benefits early, yields a similar result. This suggests that so far, households are finding ways to cope with the negative economic impact associated with the loss of benefits. Indeed, the fact that jobless workers may be digging into accumulated savings to maintain their spending habits while they search for a job may help explain the narrowing of the spending gap between the two groups. Additionally, aspects of the American Rescue Plan, such as the enhanced Child Tax Credit, which makes payments of up to $250 per month for eligible children aged 6-17 and $300 for those under 6, may also be helping to stabilize spending. The disbursement of these payments began on July 15th and will continue through to the end of the year.

Studies that make use of more detailed data find a clearer negative impact at the individual level. Case in point, a recent collaborative study, which uses anonymous bank transaction data, finds that a loss in benefits led households to cut their weekly spending by about 20%. Meanwhile, at the aggregate level, the economies of states that cut-off benefits early are estimated to have seen a reduction in spending of about $2 billion. Extrapolating from these estimates (for illustrative purposes given the many caveats), the authors suggest that a back-of-the-envelope calculation would point to a reduction in spending of about $8 billion during September and October, following the expiration of benefits in the remaining states.

End to the Evictions Moratorium May Accentuate Negative Spending Impact

Unemployment and difficulty in paying shelter costs tend to go hand in hand. From the beginning of the pandemic until very recently, a nationwide moratorium on evictions had helped protect vulnerable tenants from being evicted. The original ban expired on July 2020, at which point the CDC then issued a series of its own moratoriums. The latest iteration, which was set to expire this October, ended abruptly last month through a Supreme Court decision. As a result, millions of Americans who are behind on rent now face an increased risk of eviction. A recent analysis from CBPP, which tracks the pandemic's hardships on food, housing and employment, estimates that some 11 million adults living in rental housing — 16 percent of adult renters — were not caught up on rent as of data collected through July 2021.

Putting the near-term Delta-driven economic speedbump aside, an improving labor market backdrop should help provide some positive offset. Congress has also allocated roughly $47 billion dollars toward rental assistance. If distributed in an orderly fashion, these funds could play a significant role in softening the pandemic's blow, with benefits extending not only to rental households but also to the landlords that serve them. So far, however, the experience points to a very slow rollout of these funds. At the end of July, only about 11% of the allocated funds had been distributed. If the slow rollout continues, affected households will be forced to further reign in their spending in order to try and make rental payments and avoid eviction. Ultimately, this will be an added hurdle for struggling households that have recently lost enhanced unemployment benefits, and one that is likely to further accentuate any moderation in spending. The pace of overall U.S. consumer spending has already recorded a rapid deceleration from double-digit gains in the first two quarters of 2021. Based on available data so far, we see consumer spending tracking in the low single digits in the third quarter. This leaves a thin margin for error and speaks to the vulnerabilities that may flow.

Impacts will vary by state and region. An August snapshot of the share of households that are behind on rent payments points to significant variation throughout the country (see Table 1). States like Kentucky, Arkansas, Georgia, Alabama and New York were among the most exposed on this front as at the end of August, with over 20% of rental households in these states behind on rent. At the other end of the spectrum were states like Vermont, Utah, Indiana and New Hampshire with only about 3-6% of households in these states behind on rent (note that in some cases shares vary widely when comparing the first and second half of the month).

Table 1: Share of Households Behind on Rent (%)

| State | Aug 4-16 | Aug 18-30 |

| United States | 15 | 15 |

| Alaska | 10 | 12 |

| Alabama | 21 | 21 |

| Arkansas | 20 | 24 |

| Arizona | 9 | 7 |

| California | 14 | 13 |

| Colorado | 7 | 7 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 13 |

| Delaware | 13 | 8 |

| Dist of Columbia | 10 | 15 |

| Florida | 18 | 18 |

| Georgia | 13 | 22 |

| Hawaii | 16 | 9 |

| Iowa | 18 | 13 |

| Idaho | 11 | 6 |

| Illinois | 18 | 19 |

| Indiana | 7 | 5 |

| Kansas | 12 | 9 |

| Kentucky | 19 | 26 |

| Louisiana | 27 | 16 |

| Massachusetts | 10 | 10 |

| Maryland | 20 | 13 |

| Maine | 6 | 20 |

| Michigan | 18 | 15 |

| Minnesota | 7 | 11 |

| Missouri | 20 | 19 |

| Mississippi | 14 | 18 |

| Montana | 12 | 12 |

| North Carolina | 28 | 16 |

| North Dakota | 4 | 20 |

| Nebraska | 12 | 10 |

| New Hampshire | 12 | 5 |

| New Jersey | 25 | 19 |

| New Mexico | 17 | 16 |

| Nevada | 13 | 15 |

| New York | 18 | 25 |

| Ohio | 8 | 10 |

| Oklahoma | 18 | 16 |

| Oregon | 9 | 11 |

| Pennsylvania | 23 | 9 |

| Rhode Island | 15 | 9 |

| South Carolina | 19 | 21 |

| South Dakota | 10 | 8 |

| Tennessee | 13 | 14 |

| Texas | 13 | 13 |

| Utah | 6 | 5 |

| Virginia | 17 | 8 |

| Vermont | 6 | 3 |

| Washington | 12 | 8 |

| Wisconsin | 13 | 10 |

| West Virginia | 28 | 14 |

| Wyoming | 25 | 18 |

The picture painted by these figures, however, lacks some important color. For starters, when it comes to gauging the potential impact on spending, it is not only the share of affected households that matters, but also how far they are behind on rent. Looking at estimated rental debt levels by state reveals that households living in coastal (and typically more expensive) markets such as California, Washington, New York, New Jersey, along with those in Hawaii, Texas and Florida tend to be furthest behind on rent.2 In addition, as mentioned earlier, a speedy disbursement of rental assistance funds can have a significant positive impact. As such, states and local governments that manage to improve these processes may also be able to reduce vulnerabilities in short order, thereby improving their position vis-à-vis other states. The fact that states can issue their own eviction bans is an added caveat. A handful of states, such as California, Illinois and New Jersey have issued their own versions of the moratorium, which are poised to continue offering some protection for vulnerable households in the very near-term (for more detail see here). Lastly, the fact that the legal eviction process tends to move at different speed across states must also be considered.

Conclusion

While it is still early days, analyses of recent labor market data point to a very limited positive employment impact for states that ended the enhanced unemployment benefits early. On the other hand, the reduced cashflow from these benefits appears to have had a significant impact on spending for affected households, likely reducing it by 20%.

Half of all U.S. states waited for the original deadline of September 6th to end the enhanced unemployment benefits, giving their unemployed workers a bit more financial support through the summer. Still, the fact that the end of unemployment benefits is being accompanied by the sudden end of the eviction moratorium is a combination for more cautious spending behavior among affected household, thereby accentuating any negative spending impact in the near-term.

End Notes

- Another analysis from Gusto released on July 27th states "overall, employment growth in states that ended UI supplements in mid-June has been on par with those ending benefits in September".

- For estimated rental debt levels by state see analysis from Surgo Ventures (https://precisionforcovid.org/rental_arrears) and National Equity Atlas (https://nationalequityatlas.org/rent-debt).

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: