Medicaid Unlikely to Dodge the DOGE

Thomas Feltmate, Director & Senior Economist | 416-944-5730

Date Published: January 22, 2025

- Category:

- U.S.

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- President Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) task force has committed to cutting at least $1 trillion from federal spending.

- Both Social Security and Medicare will be insulated from any spending cuts, but President Trump has not extended the same assurance to Medicaid.

- Deep cuts to Medicaid would help to reduce federal outlays, but also lead to a significant increase in uninsured rates among America’s most vulnerable, making it difficult to pass through Congress.

- But Republicans could push to make other changes that would limit how states are able to draw on federal funds while simultaneously enforcing more burdensome work requirements, helping to slow future enrollment.

- Cuts to the federal government’s workforce are also on the table, but not to a degree that will meaningfully improve the U.S.’s fiscal trajectory.

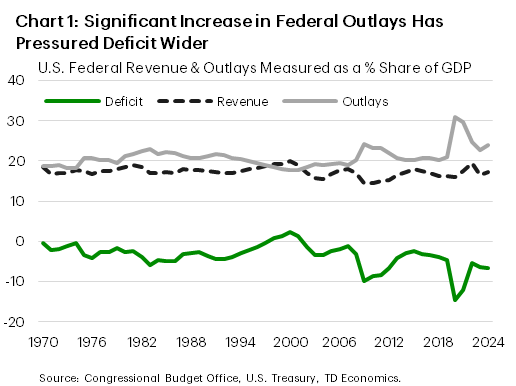

The U.S. federal deficit widened to $1.8 trillion or 6.4% of GDP in fiscal year 2024. This is more than double the annual deficit averaged over the 50-year period preceding the pandemic, as outlays – measured as a share of GDP – remain elevated relative to revenues (Chart 1). In response, the Trump administration has promised to rein in all “wasteful” federal spending and has created a special task force known as the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE), which will be led by Elon Musk.

Musk has committed to cutting federal spending by $1 trillion, or 15% of government outlays, reduced from an earlier $2 trillion target. Musk has admitted that $2 trillion was an overly ambitious goal. Over one-third of fiscal 2024 federal spending funded ‘mandatory’ programs including Social Security and Medicare, both of which Trump has said would be insulated from any spending cuts. But the same guarantee has not been extended to Medicaid, and this was an area under scrutiny by Republicans during the first Trump administration. Deep cuts to Medicaid would help to reduce federal outlays but would also result in a significant increase in uninsured rates among some of the most vulnerable Americans. For this reason, it could prove difficult to get through Congress, even with the Republicans controlling both chambers.

But smaller measures are more likely to be implemented that could limit how states draw on federal funding while simultaneously making the Medicaid enrollment process more burdensome. It’s also possible that the Republicans push to cap federal spending on Medicaid, which would increasingly shift more of the cost burden to the individual states over the long run.

Cuts to the federal government’s workforce are also on the table. But probably not to a degree that will have a measurable impact on the 160 million U.S. economy-side workforce, nor meaningfully improve the U.S.’s current fiscal trajectory.

How is Current Spending Allocated?

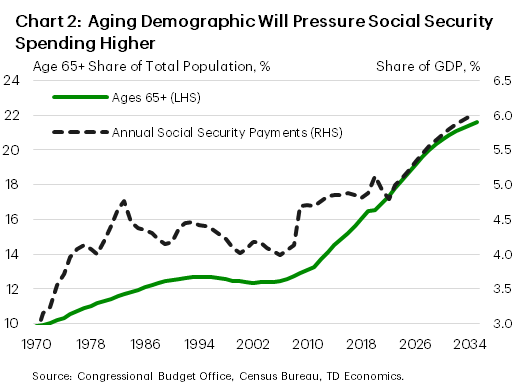

Federal spending for fiscal year 2024 totaled $6.75 trillion or 23% of GDP – up 3 percentage points from its pre-pandemic average. Of that, ‘mandatory’ spending accounted for nearly two-thirds or $4.1 trillion of overall outlays. Social Security was by far the biggest individual line item – costing $1.5 trillion – while Medicare and Medicaid costs added an additional $874 billion and $611 billion, respectively. These three programs accounted for roughly 44 cents of every dollar spent by the federal government last year. And the cost-push pressure from both Social Security and Medicare aren’t going away anytime soon due to an aging population (Chart 2). At this point, President Trump has assured that both Social Security and Medicare will be insulated from any cuts.

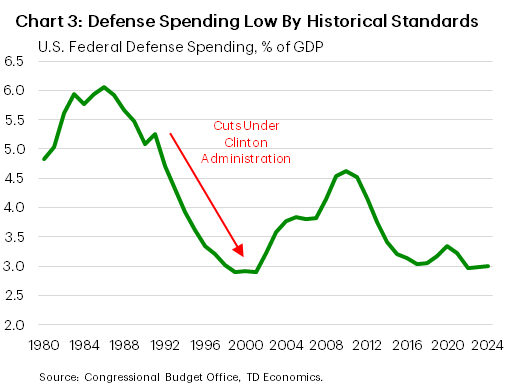

In contrast, discretionary spending, is on the chopping block. It is governed by annual appropriations in Congress, and accounted for $1.8 trillion of federal spending, with defense appropriations amounting to roughly half of those outlays. However, when measured as a share of GDP, defense spending remains historically low (Chart 3). In fact, the ratio is not far off from the end of President Clinton’s second term, following eight years of cuts. During this time, government appropriations on defense spending fell from nearly 5% of GDP in 1993 to a low of 2.8% by the early-2000’s. But this was achievable, in part, because of the high starting point created by the cold-war era. Today’s already low level and the current geopolitical backdrop leaves less scope for meaningful cuts.

It’s a similar story for non-defense discretionary spending, which funds an array of federal activities including education & social services, transportation, income security, veteran’s health care, homeland security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Measured as a share of GDP, it too remains low by historical standards, probably because it historically has fallen into lawmakers’ crosshairs when trying to rein in government spending. Over the last decade, non-defense discretionary spending has barely kept pace with nominal GDP growth, suggesting there’s little room for further cuts. That said, one could also argue that if the government is becoming more efficient, then perhaps benchmarking to prior decades’ share of GDP is too conservative of an assumption. This would suggest that there could be some room to make cuts without meaningfully disrupting government services. However, even a 25% cut to non-defense discretionary spending only gets DOGE $225 billion in savings, still a long way from their goal.

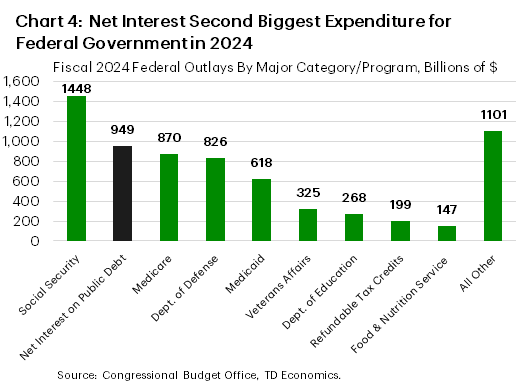

The remaining cost pressures stem from servicing the national debt. The combination of sharply rising debt and interest rates have significantly increased the cost of borrowing in recent years, with interest costs totaling $949 billion in fiscal 2024. This has surpassed all other spending categories except for Social Security! (Chart 4) Reducing interest costs will require some combination of lower aggregate spending, increased tax revenue and lower Treasury yields.

Medicaid and ACA Cuts Likely on the Table

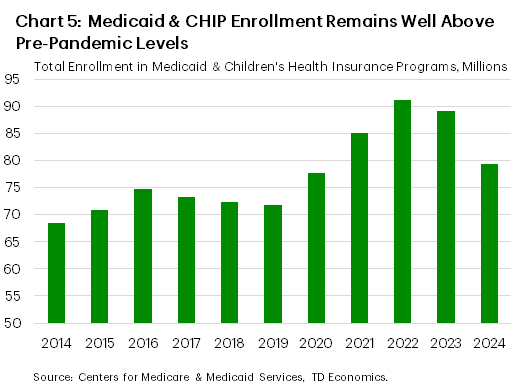

A look at past budgets put forward by both the prior Trump administration and the Republican Study Committee show that at least some Republicans support deep cuts to Medicaid . Currently, there are over 72 million American’s enrolled in Medicaid, with another 7 million relying on Children’s Health Insurance Programs (Chart 5). This is down from its peak in 2022, where enrollments surpassed 92 million when pandemic-driven measures prohibited states from disenrolling beneficiaries in exchange for a significant increase in federal funding. Those provisions expired in March 2024, causing enrollments to start to normalize, albeit remain 11% above pre-pandemic levels.

In the past, Republicans have proposed pulling on several levers to reduce Medicaid expenditures. The first would be to institute either per-capita spending caps or block payments. Under the current federal-state financial partnership, the federal government pays a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid costs. However, by imposing caps, each state would receive a fixed amount of federal funding per-beneficiary. This fixed lump payment from the federal government transfers the remaining burden of payment to states. If the average per-capita costs (or total in the case of the block payment) rises faster than the fixed amount received, the state would have to absorb the difference. Over time, the caps are unlikely to keep pace with rising health care costs, shifting more of the burden to the individual states. Under either structure, states would have to offset the rising burden by either cutting spending in other areas or raising taxes to help pay for the program. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a report in 2022 that found imposing per-capita caps could reduce federal Medicaid outlays by nearly $900 billion over the next decade. However, this would be met by a significant increase in uninsured rates, as most states would likely try to limit cost pressures by cutting eligibility and/or benefits.

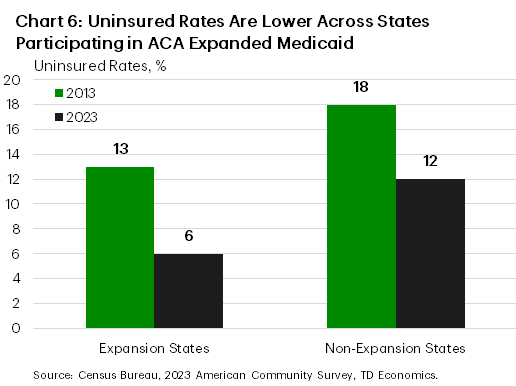

Republicans have also floated rescinding the Medicaid expansion program that first came into effect as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014. The program expanded Medicaid coverage to nearly all individuals with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty line. To date, all but 10 states have adopted the expansion, resulting in a notably lower uninsured rate across participating states (Chart 6).

Under current law, the federal government pays up to 90% of the expansion cost, which totaled about $165 billion in fiscal 2024 or roughly one-quarter of overall Medicaid costs. However, Republicans have in the past suggested equalizing the matching rate, shifting more of the cost to individual states. While the CBO has estimated that this could save the federal government over $600 billion over the next decade, it would also likely result in many states dropping out of the program – leaving millions of individuals uninsured.

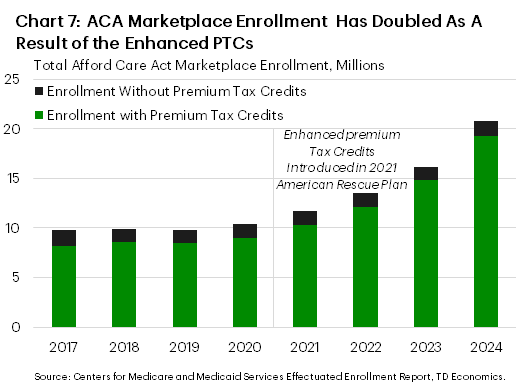

Also on the chopping block are the Affordable Care Act (ACA) ‘enhanced’ premium tax credits. Premium tax credits (PTC) have always been part of the ACA and are a federally financed subsidy that helps eligible households lower their premiums to enroll in qualified health plans offered through ACA exchanges. To be eligible, an individual’s income must be at or above 100% of the federal poverty line (FPL) but no more than 400% of the FPL, which equates to an annual income of $125,000 for a family of four. The ‘enhanced’ PTC was first introduced as part of the 2021 American Rescue Plan and later extended as a reconciliation measure under the Inflation Reduction Act. It helped to expand eligibility by eliminating the maximum income threshold and ensured that individuals spend no more than 8.5 percent of their household income on premiums. Following the enactment of the enhanced PTCs, enrollment in the ACA marketplace doubled (Chart 7). The CBO has estimated that it would cost $335 billion over the next decade to make the enhanced PTCs permanent.

Nothing is Off the Table

In terms of potential changes to Medicaid, nothing can be completely ruled out. However, some are more likely than others. For starters, any major overhaul to Medicaid funding would require Congress’s approval and this could be challenging given Republicans narrow margin in the House. This is exactly what happened in 2017 when the prior Trump administration tried to “repeal and replace “Obamacare” and significantly cut federal support for Medicaid but were ultimately unsuccessful. At the time, Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress and had an even larger majority in the House than they do today.

Conversely, for the enhanced PTCs, so long as Republicans do nothing, will lapse at the end of this year. This is the most likely outcome, particularly given the cost to extend the enhanced tax credit over the next decade. Should the enhanced PTCs sunset, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that premiums will rise across every state, with the average annual premium increase ranging from $360 to $1,860.

Outside of cuts to federal funding, Republicans are also entertaining changes in regulation which would make it harder for states to draw on federal support. For example, states currently have flexibility to finance the non-federal share of their Medicaid contribution. However, Republicans have proposed restricting or perhaps even eliminating health care taxes on providers, which nearly all states rely on to help finance their Medicaid costs. Other changes could include eliminating coverage for those that don’t meet burdensome work requirements and putting in place more verification procedures, thus making it more difficult to enroll or renew coverage. All the above are potential changes that are likely under consideration.

Will Slashing Federal Employment Generate Savings?

Elon Musk has also said that there’s potential to reduce government hiring. This has precedence. During President Clinton’s push to “end the era of big government”, federal hiring was reduced by nearly 500 thousand between 1993 and the early-2000s.

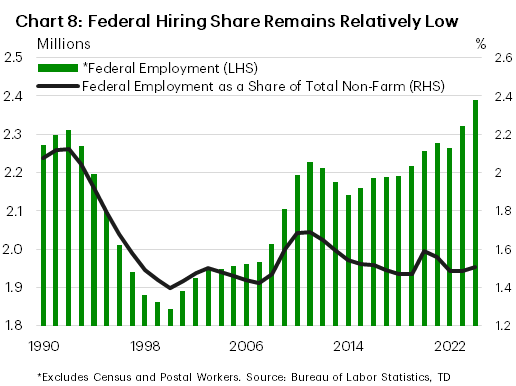

Today, the federal headcount (excluding postal and census workers) sits at 2.4 million or roughly 100 thousand above its pre-pandemic level (Chart 8). Of that, over one million work in the Department of the Army, Navy, Airforce, Defense or Homeland Security, and nearly 500 thousand are employed in Veteran Affairs. The remaining 900 thousand are spread across the other various federal agencies.

In looking at the federal government’s share of total employment, it currently sits at 1.5% or about a tenth higher than where it landed following Clinton’s second term. If this were to return to the Clinton-era, a 100k-200k reduction in headcount would not have a major impact on government spending. Total federal compensation accounts for roughly 4% of overall annual federal outlays, so even trimming by the upper-end of that range would only generate around $25 billion per-year in savings or roughly $300 billion over the next decade.

Bottom Line

At this point, the details of DOGE remain relatively vague. But with President Trump already assuring that Social Security and Medicare would be sheltered from spending cuts, and federal discretionary spending low by historical standards, the focus is likely to fall to Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act for big budgetary savings. However, deep cuts to these programs would significantly increase the uninsured rates among the most vulnerable Americans, making it politically unpopular within some states. However, some changes are likely, such as spending caps on Medicaid or new regulations that make it more difficult for states to draw on federal funds. It’s also possible that Republicans push for work requirements and/or more rigorous verification procedures going forward, all of which could reduce enrollment, helping to generate savings at the federal level over time.

Conversely, other ‘cuts’ to the Affordable Care Act are likely to happen organically. The enhanced PTCs that were first introduced as part of the American Rescue Plan in 2021 are set to expire at the end of 2025. It’s unlikely that the enhanced tax credits are extended.

Lastly, some cuts to federal hiring could also be on the table, but the magnitude will only help on the margin to control budgetary costs and not be the gamechanger in bending the U.S.’s fiscal trajectory over the next decade.

End Notes

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Congressional Republicans’ Budget Plans Are Likely to Cut Health Coverage https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/congressional-republicans-budget-plans-are-likely-to-cut-health-coverage#_ftn15

- Congressional Budget Office, Reduce Federal Medicaid Matching Rates https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58624

- Congressional Budget Office, Establish Caps on Federal Spending for Medicaid https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/58622

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Medicaid Expansion: Frequently Asked Questions https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-expansion-frequently-asked-questions-0

- Congressional Research Service, Enhanced Premium Tax Credit Expiration: Frequently Ask Questions https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R48290

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Premium Tax Credit Improvements Must Be Extended to Prevent Steep Rise in Health Care Costs, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/premium-tax-credit-improvements-must-be-extended-to-prevent-steep-rise-in-health

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: