Market Insight:

Inflation Forcing Fed Liftoff

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: January 19, 2022

- Category:

- US

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- The Fed has officially become hawkish. Over the last two weeks, the Fed has expressed the pressing need to raise its policy rate and end emergency-level monetary support.

- With inflation at multi-decade highs and the labor market continuing to show incredible strength, there is a growing risk that the Fed is already behind the curve.

- With the Fed ready to swiftly hike interest rates and rundown its balance sheet, government yields have continued to rise and are establishing new highs for the cycle.

Are you ready for liftoff? In front of the Senate Banking Committee on Tuesday of last week, Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell did his best to prepare markets for the reality that tighter monetary policy is just around the corner. This was unquestionably Chair Powell’s most hawkish declaration to date. He stated that the Fed needed to move quickly and hike the policy rate “to prevent higher inflation from becoming entrenched.”

Inflation pressures have reached a boiling point, forcing the Fed to act sooner rather than later. Investors should expect a policy rate hike in March followed by the start of balance sheet run-off (i.e., Quantitative Tightening or QT) as early as April. The pull-forward of the Fed timetable on both fronts has pushed U.S. and global bond yields higher. We expect this upward yield momentum to continue over the coming months.

Someone Turn Down The Heat

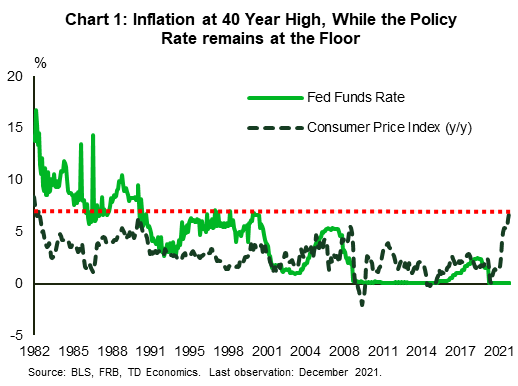

The December Consumer Price Index reinforced concerns that the Fed has fallen behind the curve. Consumer price inflation hit 7% year-on-year (y/y) in the month, a fresh 40 year high. Core prices that strip out volatile food and energy components are running above 5% y/y, more than double the Fed’s target of 2%. That is the biggest miss since the adoption of inflation targeting (Chart 1). The last time inflation was this high, the fed funds rate was 14% (compared to 0% today). To explain the inflation overshoot, Powell stated what we all know. That there “is a mismatch between demand and supply [and] that we have very strong demand in areas where supply is constrained.”

It is important to recognize what the Fed can and cannot do in its fight against inflation. First off, it can’t do much to address the supply side. It can’t release barrels of oil onto the market, nor can it accelerate semiconductor production in Taiwan. But, soaring demand has been a significant driver of the supply crunch, and on that side, interest rates matter. The Fed cut rates to zero in early 2020 to boost demand and limit the downside for GDP growth and inflation. It has largely achieved that goal – economic output is in line with its pre-pandemic trend, the unemployment rate is below the median Federal Open Market Committee members’ forecast, and inflation is well above its 2% objective.

Maintaining price stability will now require the Fed to step away from these emergency level supports. Higher interest rates will slow demand, and with some help on the supply side, hopefully bring inflation toward its objective.

The Rise In Yields

Financial markets are ready for the hiking cycle. Since the start of the year, futures markets adjusted pricing to reflect the Fed’s newfound aggressiveness. This caused the U.S. 2-year and U.S. 10-year Treasury yields to jump to 1% and 1.9%, respectively. We’d argue there is more adjustment to come on both the short and long-end of the yield curve.

Short-term yields should continue to rise alongside Fed expectations. As the Fed communicates a path for rate hikes extending past this year, the 2-year Treasury yield will continue to move higher. Current pricing suggests that the Fed will move the federal funds rate to 1.75% over the next two years. If the Fed delivers on that expectation, the U.S. 2-year yield should mechanically increase by 15 basis points every quarter for the rest of 2022. Our expectation that the federal funds rate will reach 2% by the end of 2023 is consistent with quarterly changes of 20 basis points per quarter. Investors, in other words, should expect continued moves in shorter-term yields over the next twelve months.

With respect to longer-term yields, the Fed has less control. It can communicate where it thinks the policy rate will land over the next decade, but markets are rarely aligned with the Fed. For example, the median expectation of Fed members for the long-term fed funds rate is approximately 75 basis points higher than the market expectation. That leaves a lot of yield upside on the table should markets correct to incorporate a higher fed funds endpoint.

There is also the impact of the Fed’s balance sheet. Over the last two years, the Fed has actively purchased around $2 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities. As a result, it currently owns around 30% of the entire stock of Treasury Notes and Bonds. The Fed did this to push down yields and incentivize debt accumulation in the economy. Again, it has succeeded. As Chair Powell reinforced this week, those asset purchases are poised to come to an end in March and begin to reverse later this year. In other words, the headwind slowing the recent rise in yields will turn into a tailwind. By our estimates, this could be equivalent to an extra one to two rate hikes over the next two years. Recall that this will be happening at the same time as the Fed is hiking its policy rate

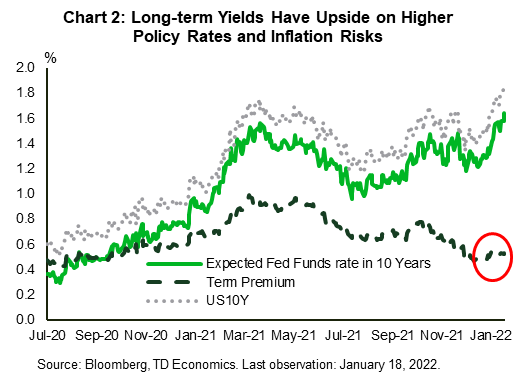

This all adds fuel to the argument that long-term Treasury yields are ripe for a repricing. Though this has started to adjust over the last few months, yields are still at stubbornly low levels. One would think that with the Fed prepared to start the hiking cycle within weeks, the U.S. 10-year yield would be a little more forward looking. Just on the expected policy rate path alone, the 10-year yield should be at 2% today. Layer on the nonexistent inflation premium, which is currently eroding the real value of Treasury investors’ returns, and the fact that the biggest buyer of Treasury securities will be running down its holdings (Chart 2), there is a compelling argument that the upward pressure could be larger.

Bottom Line

The Fed has leaned into the urgent need to raise rates and withdraw emergency-level monetary support. In Chair Powell’s own words, “we’re at a place where unemployment is now very low, historically low, and inflation is well above target, and the economy no longer needs this very highly accommodative stance of policy.” He is right. Measures of strong demand abound. We see it in overall output, but also within a historically tight labor market that has wages growing at a 4% clip. The economy is hot and to avoid getting further behind the curve, the Fed must begin raising rates in short order. With policy rate and balance sheet adjustments forthcoming, expect government yields in the U.S. and across the world to continue to trend higher.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.