Assessing the Impact of U.S. Housing Affordability Proposals

Admir Kolaj, Economist | 416-944-6318

Date Published: February 9, 2026

- Category:

- U.S.

- Real Estate

Highlights

- The U.S. administration is considering several policies to help improve housing affordability, with the focus leaning toward demand-side measures.

- Options being considered include 50-year mortgages, restricting support for large investors buying single-family homes, penalty-free withdrawals from retirement funds for home down payments, and boosting MBS purchases to lower financing costs.

- The demand-side measures being considered can help reduce barriers to entry into the housing market for buyers, cumulatively stimulating demand. But without an adequate supply-side response, the improvement in affordability from these measures could prove fleeting.

- Supply-side measures include easing regulatory barriers, releasing federal lands for housing development, reducing the capital gains tax for home sales, portable mortgages, and zoning reform. The challenge facing policymakers is that many of these policies tend to be more difficult and/or take longer to implement.

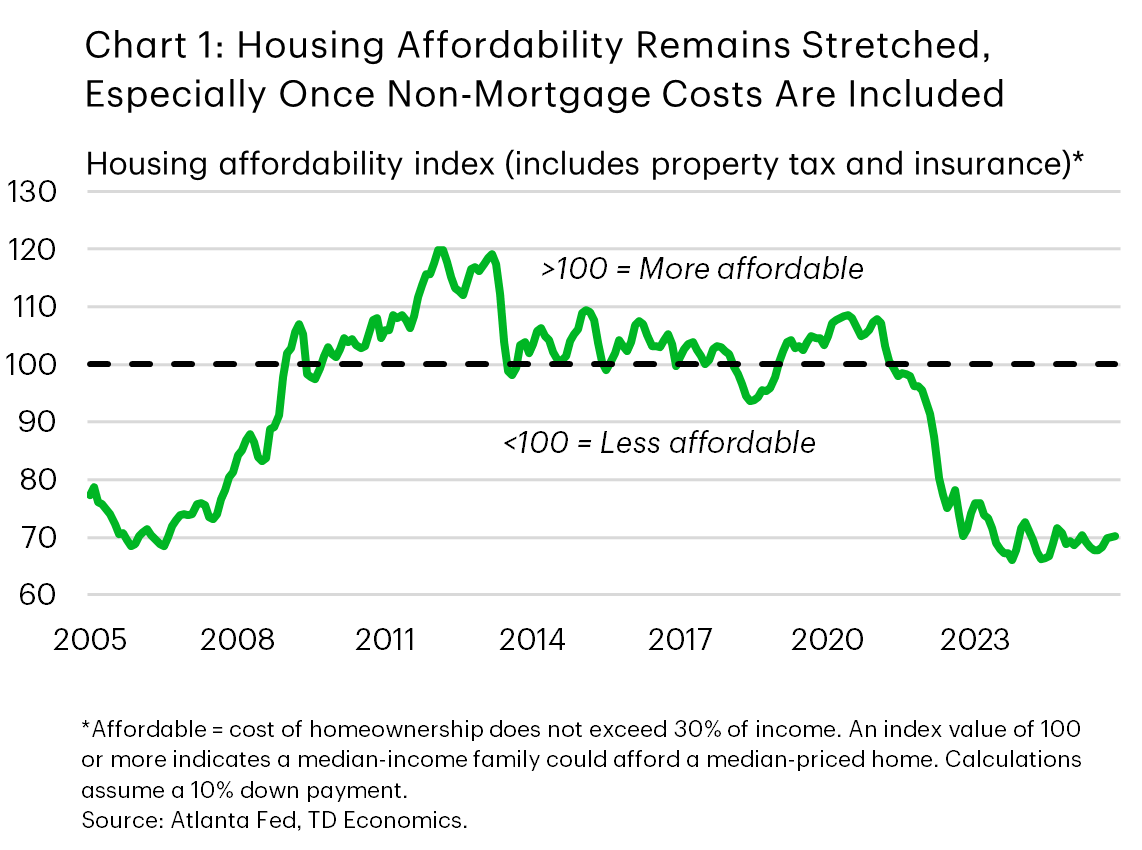

Despite some recent improvement, housing affordability in the U.S. remains well below historical norms. In response, the U.S. administration has been busy in recent weeks floating new proposals to lower the cost of housing. Much of the policy focus so far has centered on demand-side measures that aim to reduce the barriers to home buying, with supply-side proposals taking on a supporting role. While the final shape of these policies remains uncertain, we anticipate that at least a few will move forward this year. The broader question is whether the actions will deliver a durable improvement in affordability or merely provide temporary relief. To help answer this, we draw on available evidence, while also touching on international experiences where relevant.

Demand-side measures remain the focus

Lengthening the mortgage amortization period

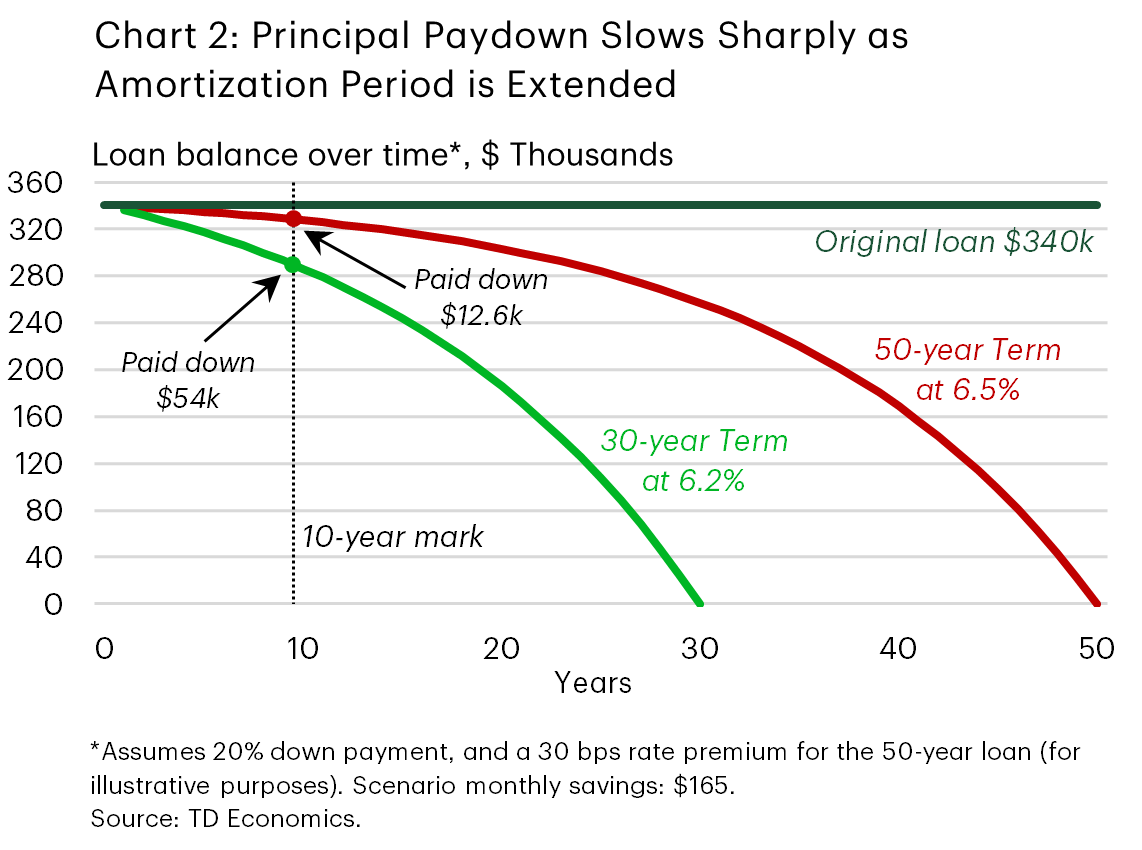

The U.S. administration is considering extending the standard mortgage amortization period from 30 years to 50 years. This could provide short-term affordability relief by lowering monthly payments. Lenders would likely charge a somewhat higher interest rate to compensate for the longer borrowing period, but even with that adjustment, our estimates suggest that payments on a median-priced home could decline by roughly $150–$250 per month under a 50-year schedule. This would help more buyers qualify for a mortgage and begin building equity.

However, equity accumulation would be notably slower, and total interest paid over the life of the loan would be substantially higher – approximately double if the mortgage were carried to maturity. That said, U.S. mortgages are rarely held to full term, with the typical loan lasting seven to ten years.1 During this shorter window, the main concern is perhaps the greater likelihood of falling into negative equity if home prices decline, given the slower principal repayment associated with a 50-year structure (Chart 2).

Insight from abroad: Canada offers a useful case study. Between 2006 and 2007, it expanded the maximum allowed amortization period from 25 to 40 years, which helped support sales activity and price momentum but appeared to deliver little long term affordability benefit. Analyzing data from these years, a BIS analysis specifies that most households would be inclined to use the longer horizon to take on larger mortgages instead of lowering monthly payments, thus raising payment to income ratios even as amortizations lengthened. In response to emerging risks – compounded by the U.S. housing meltdown – Canada reversed course quickly starting in 2008, with the amortization period reduced back to 25 years by 2012. The experience appears to have underscored the policy’s limited effectiveness. Consistent with this lesson, Canada has since avoided a broad return to longer amortizations, limiting them to narrow cases (i.e., for first-time homebuyers). The overall takeaway is that extended amortizations can modestly expand access to homeownership in the near term, but on their own are unlikely to deliver durable improvements in affordability.

Restricting institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes

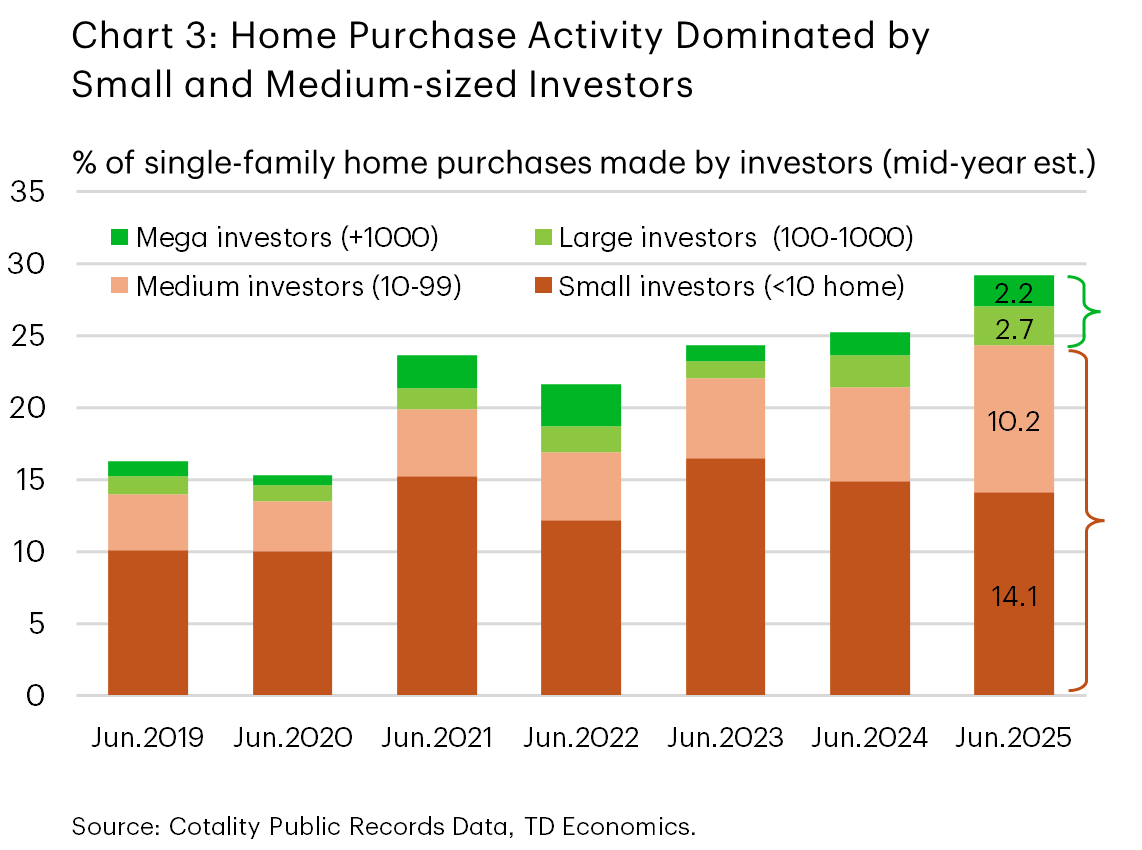

The administration has indicated it is considering “banning” large institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes. However, details from a recent executive order (EO) suggest that this will be more of a restriction rather than an outright ban. By the end of February, the Treasury must define what qualifies as a large institutional investor – an important distinction given that mega investors owning 1,000+ homes account for just over 2% of purchases, while investors with 100+ homes account for about 5% (Chart 3). By the end of March, federal agencies including HUD, VA, FHFA, and the GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) must issue guidance preventing them from “approving, insuring, guaranteeing, securitizing, or facilitating” the purchase of single-family homes by large institutional investors. A narrow carve-out remains in place for build-to-rent (BTR) communities specifically designed and financed as rentals.

An outright ban would have reduced 2–5% of investor demand, easing competition somewhat across the market. But even then, benefits to first-time buyers would be limited: smaller-scale investors – who already play an outsized role – could quickly fill part of the gap. The more moderate approach in the EO further reduces the policy’s bite, as it limits access to federal support rather than preventing these investors from expanding through other financing channels. The BTR exemption softens the impact even further. But this carve-out does carry other benefits, namely the fact that it can help preserve rental development activity.

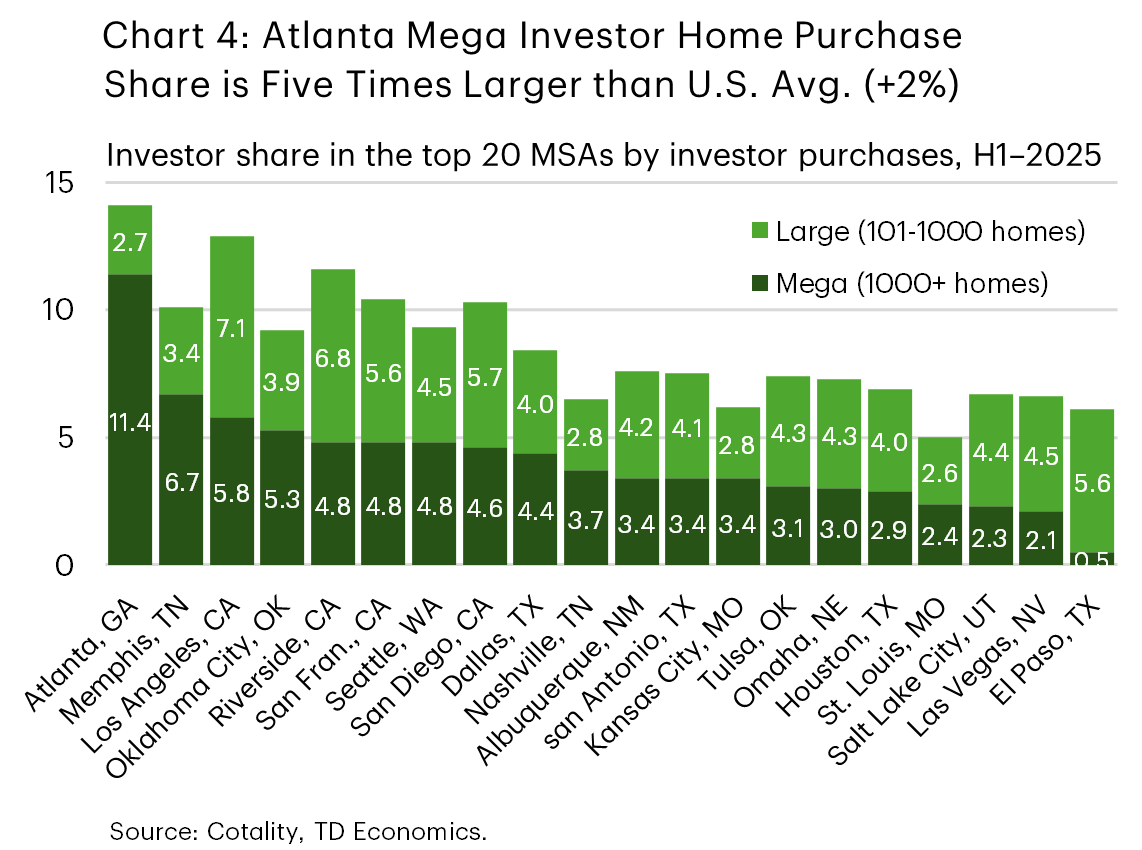

Overall, this policy should help ease competition for single-family homes at the margin, with its impact on affordability likely very limited. That said, in a few markets where large institutional investors play a much larger role, such as in Atlanta, the policy’s effects could be more noticeable (Chart 4).

Increase MBS purchases to lower mortgage costs

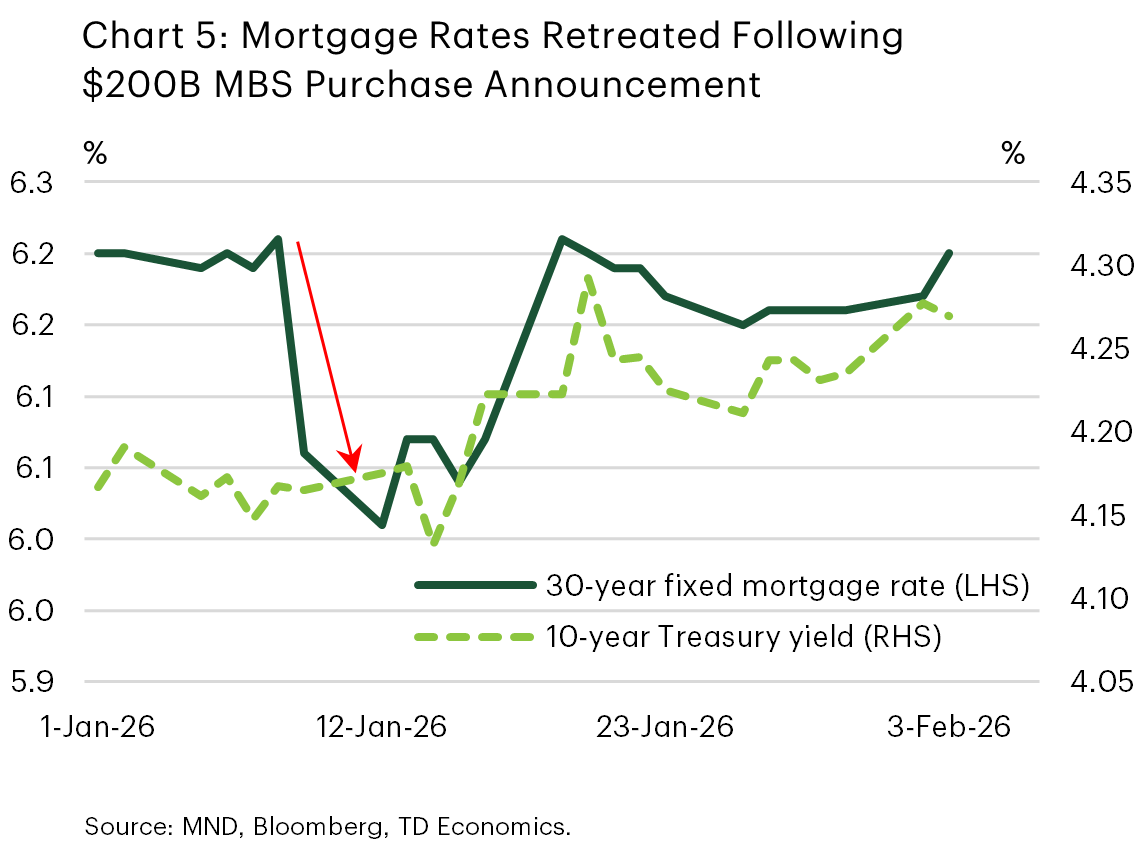

President Trump has directed the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The goal is to use the GSEs’ cash reserves to boost demand for MBS and, in turn, lower borrowing costs for homebuyers. The exact rate impact is uncertain, but likely modest given the sheer size of the U.S. mortgage market. Agency MBS – about $9.4 trillion in mid-2025 – represented roughly 65% of the total single-family mortgage debt outstanding.2 The $200 billion purchase is relatively small when benchmarked against this stock, though more meaningful when measured against annual issuance.3 In this vein, it appears that this program will “move the needle,” but likely not dramatically.

Mortgage rates did decline by about 20 basis points following the announcement, though they rebounded soon after, reflecting in part other market forces – primarily an upswing in the underlying 10 year Treasury yield (Chart 5). Several estimates point to the policy’s ultimate impact being close to the initial decline, highlighting expectations for a modest impact.4 What’s more, the effect may be short-lived. This is because the tightening in the spread between benchmark Treasury yields and MBS could be front-loaded, withering away once the purchases are priced in.5 Further intervention by way of MBS purchases to help lower financing costs cannot be ruled out, but capital requirements for the GSEs would likely be a barrier to additional action. Overall, the impact of this policy will likely be modest and potentially front-loaded, pointing to a mild near-term boost in housing affordability.

Other policy moves could be considered in concert to drive down mortgage rates more substantially. One idea that has its proponents – though not yet adopted by the administration – is to introduce mortgage prepayment penalties in the United States. The current structure of no penalty benefits homeowners by offering the certainty of a long-term fixed rate along with the flexibility to prepay without penalty when selling or refinancing. However, this flexibility comes at a cost. For instance, MBS investors typically demand additional yield to compensate for heightened prepayment risk. Introducing prepayment penalties – common in many other countries – could reduce this risk for lenders and MBS investors, potentially lowering mortgage rates. Supporters of this policy estimate the rate benefit could exceed 60 basis points, though other research suggests the benefit could vary widely with market conditions and may be materially smaller. Given that the typical U.S. mortgage lasts closer to a decade, imposing penalties when the loan is not carried to maturity (30 years) could result in many borrowers facing charges in later years. To address this, alternative designs have been discussed, such as loans with shorter lockout periods of five or ten years – something that would make the mortgage structure look more like that of Canada – though these would likely produce smaller rate reductions. Overall, while these options could help modestly lower mortgage rates, the longstanding flexibility embedded in the U.S. mortgage market may significantly limit borrower uptake.

Expand penalty-free access into retirement and educational savings for home down payments

Under current tax rules, Americans have limited ways to access retirement savings for home purchases without facing penalties. Many employer-sponsored 401(k) plans allow participants to borrow up to 50% of their vested balance – capped at $50,000 – generally repayable within five years. First-time buyers can also withdraw up to $10,000 from an IRA without incurring the 10% early-withdrawal penalty. Policymakers are now exploring whether to expand penalty-free access, and not only to retirement accounts but also to educational savings in 529 plans. The latter would represent a notable shift, as no major Western country currently allows penalty-free withdrawals from education funds for home purchases. Such policy changes could leave some households more financially vulnerable later in life, either in retirement or when funding education.

Measures that expand access to retirement funds for down payments – and meaningfully increase their use among homebuyers – would provide a demand-side boost. Larger down payments could help more households qualify for mortgages and enter homeownership. However, absent a meaningful supply response, increased purchasing power would likely translate into faster price growth, potentially eroding the initial affordability benefit over time and disproportionately rewarding early movers.

Its broader implications for retirement readiness also warrant caution. Notably, President Trump has signaled reservations – stating, “I’m not a huge fan” – which, combined with the need for Congressional approval, suggests this measure may be unlikely to find enough traction to be implemented.

Supply-side measures: Largely in the background

Supply-side policies continue to receive comparatively less attention, even though several initiatives remain in motion behind the scenes. Over the past year, efforts included steps to release federal lands for residential development and broader deregulation initiatives aimed at lowering construction costs. Policymakers have also floated the idea of reducing capital gains taxes on home sales, and more recently have turned their attention to portable mortgages as well as regulatory and zoning reform.

Releasing federal lands for development (ongoing)

The administration has pledged to release federal lands for residential development to help expand housing supply. Efforts last year included preparations to develop affordable housing on federal lands, though progress since then appears limited. In regions with large federal land holdings, the policy could meaningfully boost supply and help temper price growth. However, national-level impacts are likely to remain modest given the concentration of federal lands in the West and the competing uses they must accommodate, including conservation. Development timelines also pose a challenge. Obstacles like environmental reviews, land-transfer processes, and construction periods mean even an optimistic scenario would likely push meaningful supply additions beyond the medium term.

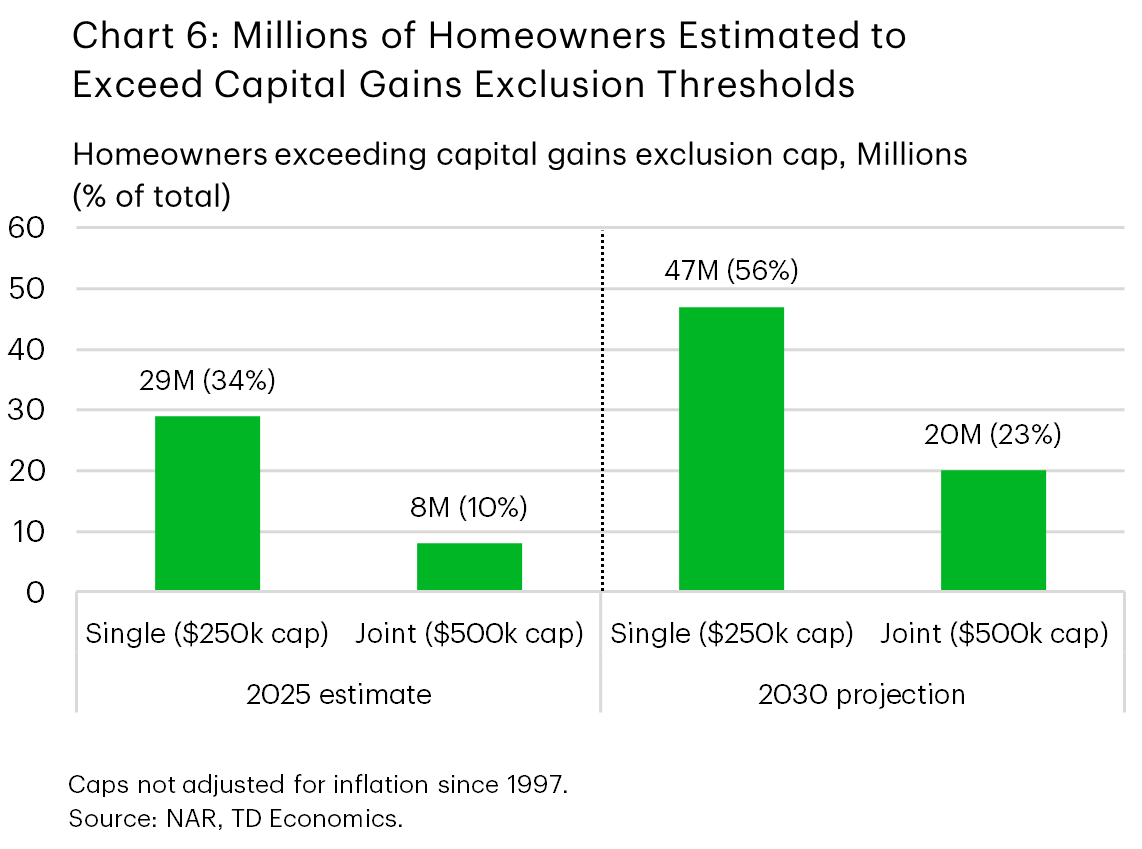

Removing capital gains tax on home sales (under consideration, floated last year)

Under current law, homeowners selling a home may face capital gains taxes on profits exceeding $250,000 for single filers or $500,000 for married couples – thresholds set in 1997 and never indexed to inflation. A recent NAR-commissioned study found that millions of homeowners may already exceed these capital gains exclusion caps (Chart 6). The administration has floated the idea of reducing the capital gains tax burden on primary home sales to encourage more homeowners to list their properties and increase for-sale inventory. Such tax changes would require Congressional approval and could be costly. Moreover, most of the tax benefits would accrue to higher-income homeowners,6 and the supply released would likely skew toward higher-priced homes – helping to ease overall inventory pressures but doing relatively little for affordability challenges at the lower end of the market.

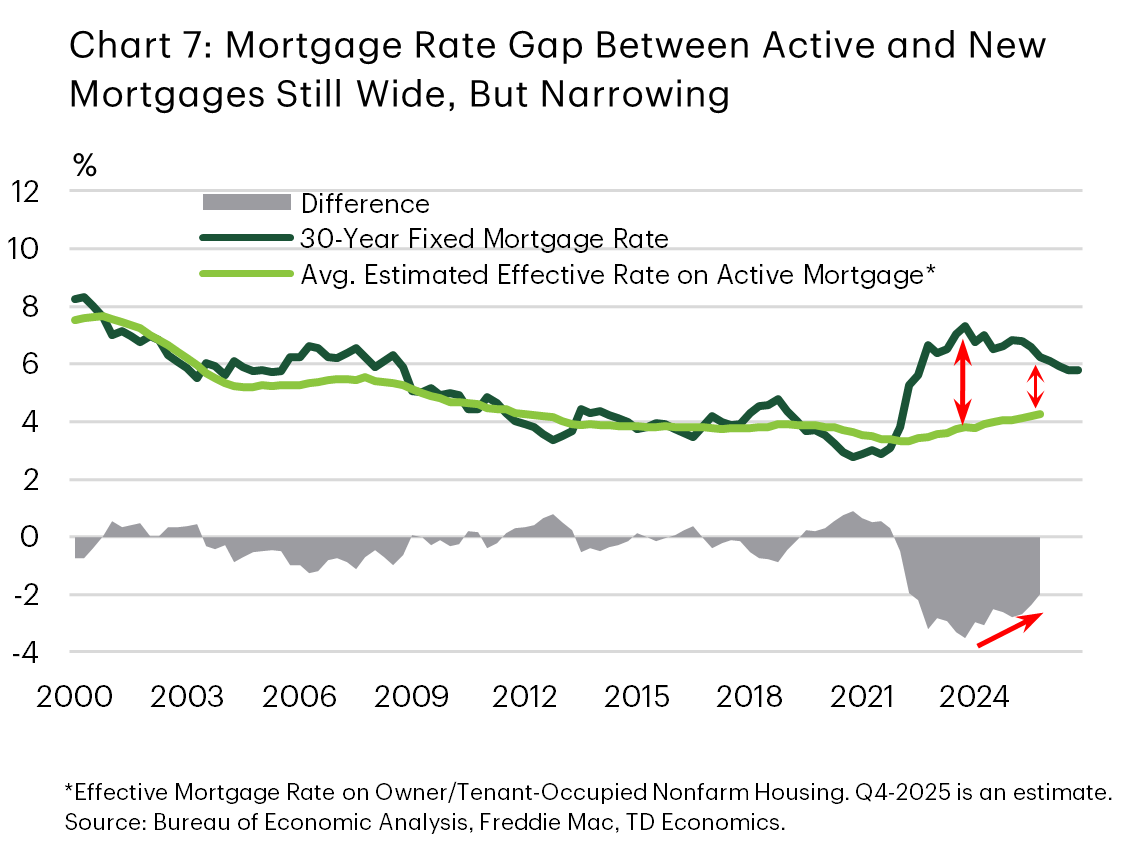

Portable mortgages (under consideration)7

Portable mortgages allow borrowers to transfer their existing interest rate and loan terms to a new property when they move, rather than taking out a new mortgage at prevailing – and currently higher – market rates (Chart 7). This feature would help address the mortgage-rate “lock-in effect,” in which homeowners delay moving to avoid giving up their low existing rate. A little over two-thirds of mortgages still carry an interest rate below 5%, and more than half have a rate below 4%. This trend has constrained the number of homes that would come up for sale in a typical year and has been a key factor in impeding the typical turnover that takes place in the housing market.

The FHFA is currently evaluating mortgage portability for GSE-backed loans as part of broader affordability efforts. Applying portability retroactively to existing loans would be difficult, given the legal and contractual hurdles involved, and the fact that it would shift risk for MBS investors by altering both the underlying security and the expected mortgage lifecycle. While workarounds – such as borrower-paid portability fees to compensate investors – are possible, the overall complexity suggests a very low probability that portability would be applied to existing mortgages.8

By contrast, offering portability on new mortgages is far more feasible. Such loans could be introduced relatively quickly without requiring Congressional approval by leveraging executive control over GSEs. They could be priced similarly to standard 30-year mortgages, though they might include an exercise fee for borrowers who choose to port their loan. However, because portability would apply only to new originations, its impact on bringing additional homes to market in the near to medium term would likely be limited. The bulk of homeowners locked into pre-2023 low-rate mortgages would remain unaffected. Instead, the benefits to market turnover would build slowly over time as portable loans become a larger share of outstanding mortgages.

Reducing regulatory barriers (ongoing)

Regulatory requirements account for nearly 25% of the cost of a typical single-family home and more than 40% of the cost of a multifamily development, according to NAHB estimates.9 Reducing these burdens can meaningfully lower construction costs and shorten project timelines, ultimately supporting faster homebuilding and more affordable prices for buyers. The administration has adopted a multipronged approach to easing these pressures. Broad initiatives – such as the “1 in 10 out” effort requiring agencies to repeal ten rules for every new one introduced – are helping streamline the overall regulatory landscape. Industry-specific measures are also advancing. For example, a congressional proposal would remove the requirement for a permanent chassis on manufactured homes – a component rarely needed after delivery. This change could reportedly lower the cost of each HUD-code home by $5,000 to $10,000. More broadly, homebuilders have called for relief from regulations related to energy-efficiency standards and local materials sourcing for multifamily projects – items that if addressed could help bring down construction costs.10 Notably, many of these changes could be implemented through executive action, offering the potential for relatively swift progress.

Zoning reform (ongoing)

The U.S. administration is considering policies to ease zoning rules as a way to expand housing supply, building on steps already taken in some states and municipalities to allow greater density. Examples of these local initiatives include permitting accessory dwelling units (ADUs), allowing multifamily structures such as duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in areas previously limited to single-family homes, and relaxing or eliminating parking requirements. Because zoning authority rests primarily with state and local governments, nationwide reform is likely to be a slow, multiyear process. To help accelerate progress, the administration is considering using federal funding as leverage. This would involve conditioning support for infrastructure, transit, and community development on local governments’ adoption of “YIMBY” (Yes in My Backyard) policies, including improvements in their permitting processes and zoning rules.

Conclusion

Looked at in isolation, none of the measures currently on the table appear to provide a silver bullet in addressing the U.S. housing affordability challenge. If various proposals are implemented collectively, there is more potential to move the needle. Even then, pulling off a sustained improvement in affordability could prove elusive. Supply-side initiatives – such as efforts to reduce regulatory barriers – hold meaningful long-term promise but tend to be challenging to execute with longer timelines. On the other hand, demand-side measures – which are stealing more of the spotlight – may be more easily implemented and quicker to bear fruit. If demand-side boosts materialize faster than supply responses, competition will intensify and price growth will pick up, with the potential to offset initial affordability gains and leave conditions much the same as before. Ultimately, supply has a central role to play when it comes to durable improvements in housing affordability.

End Notes

- The average mortgage duration is generally considered to be 7-10 years; Fannie Mae (see here). Note that in recent years, there are indications that low repayment rates, as associated with the mortgage rate lock-in effect, have likely extended the lifecycle of some loans beyond this typical range.

- “Housing finance at a glance”, Housing Finance Policy Center.

- Agency MBS issuance last year totalled roughly $1.4 trillion; SIFMA (see here). Overall MBS issuance was roughly $1.9 trillion.

- Measure is “unlikely to deliver a step-change lower in mortgage rates”, JPM.

- Details pertaining to the timing and pace of MBS purchases remain unclear as of writing.

- “Will expanding the capital gains exclusion unlock housing supply? Evidence on who benefits”, Brookings.

- Note that while clearly supportive from a supply side perspective, mortgage portability also has a demand side dimension: the ability to carry forward a low rate could encourage more homeowners to move, potentially stimulating transaction volumes.

- “How making agency mortgage-backed securities portable may impact housing and mortgage-backed securities investors”, MSCI.

- NAHB Urges Congress to Ease Regulatory Burdens to Help Housing Affordability, NABH.

- Ibid.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: