The U.S. Debt Ceiling: Playing with Fire

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: May 18, 2023

- Category:

- US

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Time is running out for Congress to raise the debt ceiling and prevent the U.S. government from defaulting on its obligations.

- The impact of a prolonged debt ceiling standoff could be greater today than in the past, especially considering the economy is operating in the later stages of the cycle, where financial vulnerabilities are far higher.

- Our baseline is that a deal will get done, but the longer the stalemate persists, the greater the odds that financial markets and the economy get burned.

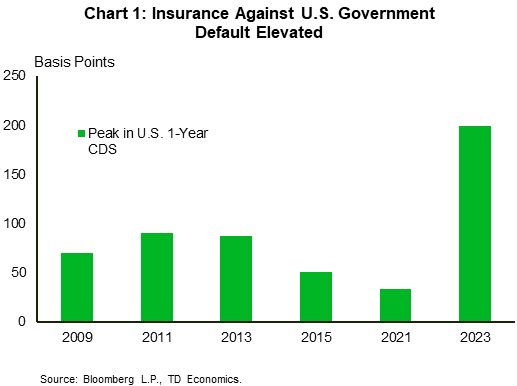

Congress is running out of time to raise the debt ceiling. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has stated that the government is estimated to be unable to pay its bills by early June, and potentially as early as June 1st (the X-date). More recently, the Congressional Budget Office backed up Yellen’s warning with similar guidance . While it seems inconceivable that the government would voluntarily allow that to happen, investors are hedging against this risk. Insurance against government default has soared to its highest level on record, more than doubling that witnessed during the infamous 2011 U.S. debt downgrade (Chart 1). Given risks already present within the economy, we believe that the current debt standoff is a much larger threat. Although this has yet to bleed into broader financial markets – with equity, credit, and currency markets hoping for resolution - politicians are playing with fire. The longer the standoff persists, the greater the risk that markets and the economy get burned.

Can’t we all just get along?

The political divide in Washington has grown over the years. The Pew Research Center estimates that Democrats and Republicans have shifted further apart in terms of ideology than at any time in the last 50 years. Researchers note that not only have Democrats moved farther to the left and Republicans to the right, but recent elections have removed many centrist Members of Congress who could help a deal get struck.

Republicans passed the ‘Limit, Save, Grow Act’ last month, which would have allowed the debt ceiling to be raised, but included deep spending cuts, work requirements to qualify for social safety net programs and other demands. Democrats had stated that they were uninterested in accepting a debt ceiling deal with strings attached. However, as formal talks have heated up in recent days, both sides appear to have eased their hard lines and have conveyed optimism that a middle ground can be reached. Still, time is of the essence, with little wiggle room in the event that talks fall apart or other roadblocks be hit.

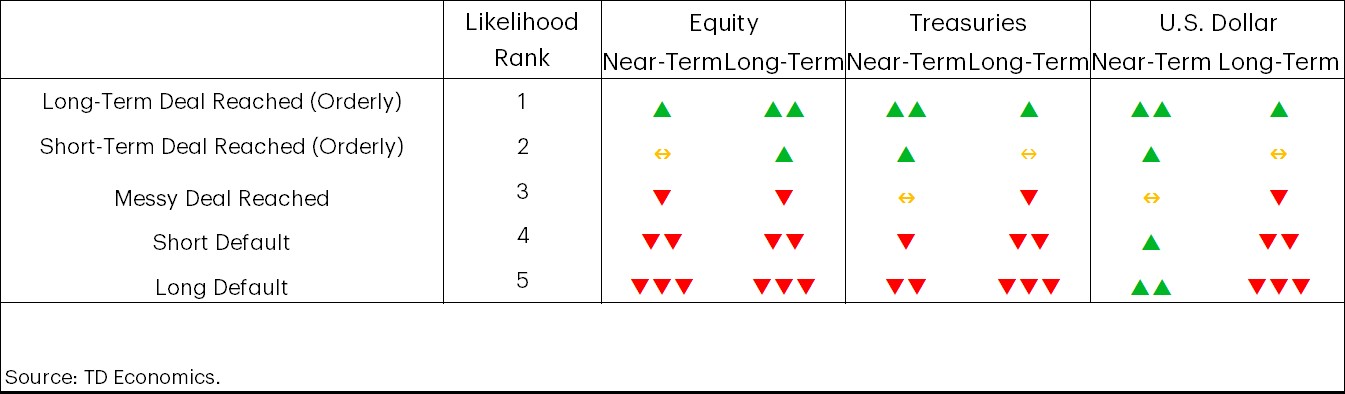

The many roads to reaching a deal

There are several ways this debt ceiling showdown could go (Table 1). Let’s start with the best and most likely scenario. That is the one where a longer-term deal gets reached in a timely and orderly fashion. It would include the $1.5 trillion (or more) debt ceiling increase the Republicans have already proposed, but the size of the spending cuts would be smaller than the nearly $5 trillion in the initial bill. In terms of market reaction, the cloud of uncertainty would be lifted, causing equities to rise. Bond markets would see yields increase as investors refocus on the Fed and the increased probability that rates would remain higher for longer. This would be favorable for the USD, which has also been closely aligned with the path of the Fed.

In terms of economic impact, this scenario would remove a key tail risk, thus increasing odds of a softish landing in the U.S. economy. Real GDP growth would average 1.2% for 2023, before decelerating to 0.8% next year under the weight of already high interest rates. The unemployment rate would follow suit, rising from an annual average of 3.6% this year to 4.4% next.

The next most optimal deal would be a short-term agreement – again negotiated in timely fashion -- that allows the Treasury to keep borrowing through this summer. Although there would be a new (though delayed) X-date, lawmakers would be given more time to bridge differences. By kicking the can down the road, the time pressure would be alleviated, bringing hope that a longer-term deal could eventually be struck. Equities, bond yields, and the USD could all rise under this scenario, but the reaction would be muted. This scenario would be mildly negative for the US. economic outlook as it still leaves a cloud of uncertainty.

Table 1

This is where things get messy

This brings us to another relatively high probability scenario, whereby a deal is reached, but lawmakers leave it to the eleventh hour. Recall that the 2011 episode that is often referenced was one where a deal got reached but the extent of brinksmanship reduced confidence in the U.S. government. The rating agency S&P responded by downgrading U.S. government debt to AA+ from AAA. Although another downgrade on brinksmanship alone seems less likely with all agencies currently maintaining a ‘stable’ rating for U.S. debt, a messy deal could cause investors to get panicky. Indeed, it is easily argued that the timing of the shock would be far worse today than in 2011 given that it would be hitting late in the cycle, when financial vulnerabilities are far higher.

As such, we would expect equities to drop sharply, with a flood into safe haven assets. The U.S. would still maintain its safe haven status in this scenario, causing flight into U.S. dollars and preference to long-duration Treasuries. If any resulting risk-off move is pronounced enough – even if only temporary – it could tip the U.S. economy into a technical recession and pull forward increases in the U.S. unemployment rate.

Given that a recession could occur even with a messy deal, scenarios that breach the X-date would act to increase the severity. That said, the duration matters. While only time would tell, we believe that a short-lived default would likely lead to financial and economic impacts not far off the brinksmanship scenario just discussed. In that case, the government would fail to pay all of its bills for a short time, but a likely dramatic sell-off in equities and likely rating agency downgrades would motivate lawmakers to swiftly get a deal done. Short-term Treasury yields would rise on the threat of a missed payment, but long-term yields would fall. The USD would rise as the threat of financial market stress would cause investors to sell more risky currencies abroad.

If the X-date is reached and lawmakers fail to reach an agreement for a more protracted period (say, beyond 1-2 months), then we would clearly be getting into unchartered waters. Not only would financial market impacts be more dramatic and sustained, but the inability for the government to spend money on counter cyclical supports for consumers and businesses would act as a fiscal cliff. Economic impacts would thus be non-linear and akin to a severe downside stress. For example, the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers estimates that the unemployment rate would rise to a level similar to what happened in the Global Financial Crisis, with real GDP contracting by as much as 6.1 percentage points. The Council also projects a drop in equity values by 45%, with investors exiting any kind of risk, including soon-to-mature Treasuries. Given the U.S. Treasury’s market size, there may be few options for investors seeking safety. They would instinctively buy longer-dated Treasuries and U.S. dollars with no other alternatives. But the long-term impact of lost confidence would embed permanently higher yields in U.S. Treasuries and a lower resting point for the USD as investors look for alternative safe assets.

Bottom Line: Starting Points Matter

It is clear that a deal needs to get done. And the earlier the better. While some commentators have proposed backdoor solutions like minting a trillion-dollar platinum coin, using the legal angle in the 14th Amendment, or prioritizing payments, an actual agreement is the only real solution. And for other commentators that seem relaxed about pushing to the eleventh hour or even allowing a default, our analysis above points to an economy that has little room to absorb this shock.

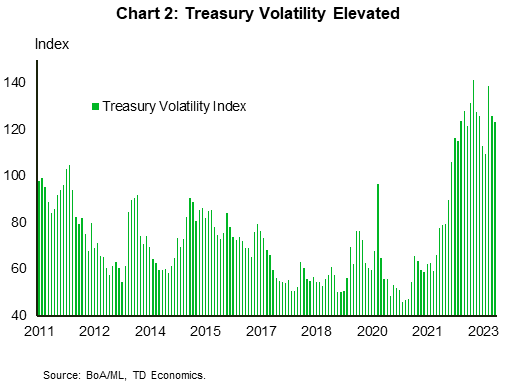

Our economic forecast already has U.S. GDP growth hovering around zero growth for the rest of this year. The lagged impact of the Federal Reserve’s historic interest rate hiking cycle is starting to take hold, while the U.S. regional banking sector is acting as a significant headwind. Financial markets are more vulnerable now than in the past. In 2011, the Fed’s policy rate was at 0.25%, with quantitative easing ongoing. Now, after 500 basis points in rate hikes, the bond market is under stress with the Treasury volatility index at its highest level since 2008 (Chart 2).

The vulnerability of markets has bond yield risk skewed to the upside. Equities too are at risk. As we saw during 2022, rapidly rising yields can be bad news for stock prices. And while the USD rose 13% over the last two years, it has room to drop should investors sour on the U.S. This increase in market sensitivity means that if politicians aren’t careful, what would have been a short-term flare-up in markets in the past, could turn into a financial market blaze.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: