Assessing the Feasibility of President Trump’s Tariff Dividend Checks

Thomas Feltmate, Director & Senior Economist | 416-944-5730

Date Published: December 5, 2025

- Category:

- U.S.

- Government Finance & Policy

- Consumer

Highlights

- President Trump recently floated the idea of sending out $2,000 ‘tariff dividend checks’ to Americans.

- Details remain sparse, but assuming the checks are limited to income filers earning less than $80,000 per year ($160,000 for couples filing jointly), the program would cost upwards of $250 billion – wiping out most of next year’s expected tariff revenue.

- Assuming the checks are disbursed ahead of next year’s midterms, we estimate that they could add nearly three-quarters of a percentage point to 2026 consumer spending. But they would also add to inflation and likely delay some of next year’s expected rate cuts.

- With Congress showing a reluctance to undertake further spending measures that will add further pressures to the deficit, it’s unlikely that the President’s plan will be implemented.

President Trump has recently proposed sending out $2,000 ‘tariff dividend checks’ to eligible households, which would be funded using tariff revenue. However, the administration has not provided further details on the structure, timing or income testing thresholds, making any sort of economic inference very speculative.

Even using conservative assumptions, where rebate checks are restricted to individual tax filers earning below $80,000 per year ($160,000 for joint tax filers) we estimate that the impact on consumer spending could be meaningful – adding as much as three-quarters of a percentage point to 2026 PCE. But this would also feed through to inflation and almost certainly alter the Fed’s reaction function. Moreover, the cost of the program would be significant, effectively wiping out all of next year’s expected tariff revenue. This could be unsettling to bond markets, which have already become unnerved with the U.S.’s unsustainable fiscal trajectory.

Tariff Rebate Checks – Unlikely to Materialize

According to President Trump’s November 9th Truth Social post, “A dividend of at least $2,000 a person (not including high income people!) will be paid to everyone”. In a subsequent press conference, the President said the checks would come “probably in the middle of next year”, “or a little bit later than that”. However, we remain skeptical that they will come at all.

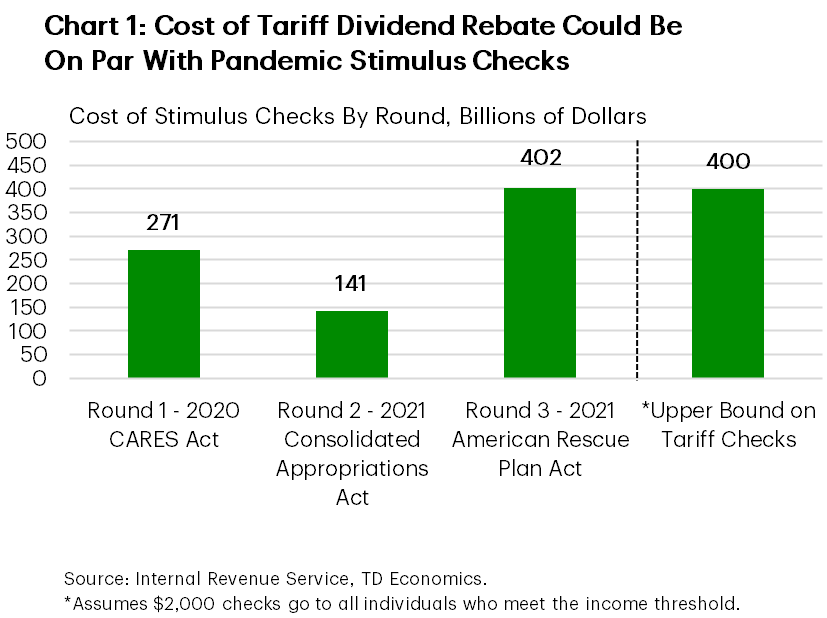

For starters, the cost of the program is likely to be significant. Following similar income thresholds that were applied to the three rounds of pandemic stimulus checks, and assuming all individuals receive a $2,000 rebate (children included), we estimate that the program could cost upwards of $400 billion dollars. For the record, that’s larger than the first two rounds of pandemic checks, and on par with what was included in the 2021 American Rescue Plan (Chart 1). Importantly, the cost of the program would eclipse next year’s expected tariff revenues, which are likely to be between $300-$350 billion. This would result in an even further widening in the deficit, which is already expected to be 6.5% of GDP.

This will not sit well with Congress, who ultimately holds “the power of the purse” and has final say over whether the President’s tariff rebates will materialize. Republican deficit hawks including Sens. Rand Paul (R-KY) and Ron Johnson (R-WI) were already reluctant to back the President’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) because of its impact on the deficit. The proposed rebates would only magnify these concerns. But beyond the deficit hawks, other more moderate officials including Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) have struck a cautious tone, noting that he would like to see the increased tariff revenue used to reduce the deficit. Democrats have so far been quiet on the issue, but given the administration is likely using this as a tactic ahead of the mid-term elections, it’s unlikely to garner much support from the other side of aisle.

Another obstacle is the ongoing Supreme Court challenge on President Trump’s use of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose certain levies, like the reciprocal and fentanyl tariffs. Should these be struck down, it would deal a significant blow to not only the administration’s tariff agenda, but also the revenue stream required to fund OBBBA and the rebate checks.

Packing Economic Punch…

Beyond the deficit considerations, there’s also good reason to question why the administration would be imposing further fiscal stimulus at a time when the tailwinds from OBBBA haven’t even been felt. To get a sense of the economic impact that the dividend checks could generate, we construct two plausible, alternative scenarios:

Scenario 1 assumes all income filers earning under $80,000 per year (joint filers at $160,000) receive the full $2,000 rebate, but earners above the threshold get nothing. The checks are assumed to go out ahead of next year’s mid-terms, in Q3-2026 and are estimated to cost ~$250 billion.

Scenario 2 assumes the same income threshold as Scenario 1, but the checks are assumed to be half the size and go out in two tranches: $1,000 in Q3-2026 and $1,000 in Q3-2027. This better aligns to how President Trump has described the checks as being a “dividend payment”, suggesting it could be reoccurring.

Because the stimulus is targeted at lower-and-middle income households, who are more liquidity constrained, it’s assumed that most of the stimulus is spent. This happens over a two-year period, which loosely follows the drawdown trajectory of the pandemic-related excess savings.

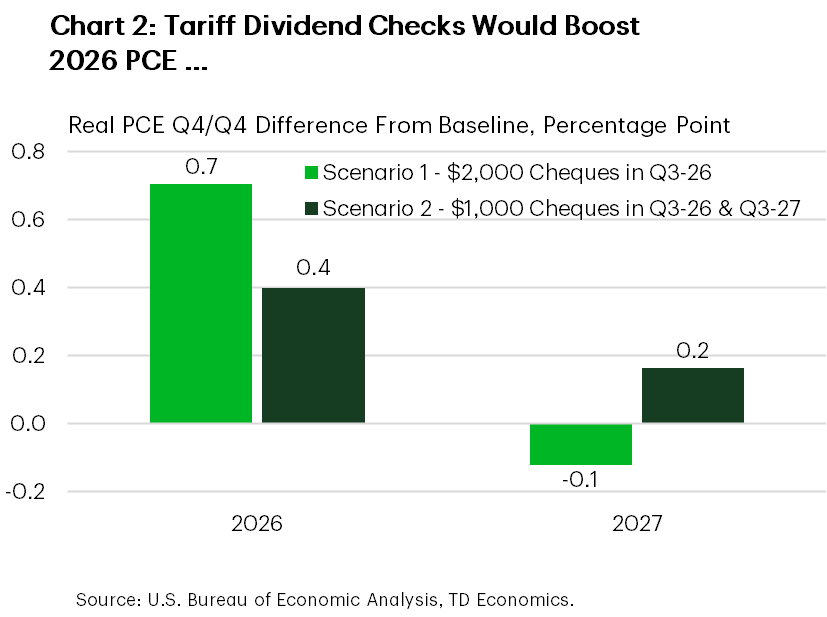

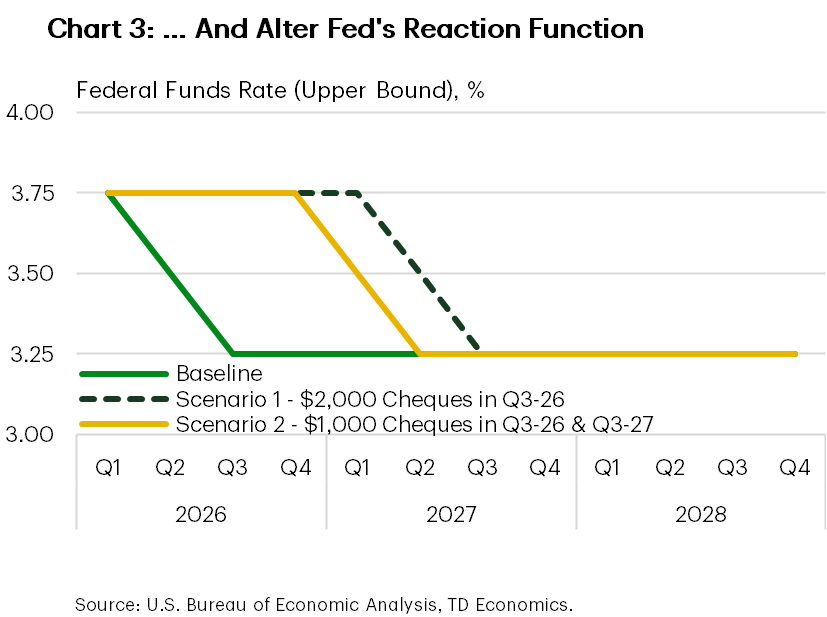

Relative to our baseline forecast, household consumption under Scenario 1 is lifted by 0.7 percentage points in 2026 (Chart 2) – bringing it to 2.8% on a Q4/Q4 basis. This would be a meaningful acceleration from 2025, where it’s expected to end the year at 1.5%. Because the stimulus is coming at a time when the economy is still somewhat overheated and running slightly above potential, the additional spending generates modest inflationary pressure. Core PCE inflation is estimated to rise an additional 0.2 percentage points in both 2026 and 2027. This alters the Fed’s reaction function, with the 2026 rate cuts in Q2 and Q3 assumed in our baseline, pushed out by a year (Chart 3).

In Scenario 2, the initial impulse to household consumption is less, reflecting the smaller fiscal transfer. However, because there’s two rounds of checks, the tailwind is sustained over a longer period. Household consumption is lifted by 0.4pp in 2026 and an additional 0.2pp in 2027. Relative to the baseline, the level impact to inflation is similar in both Scenario 1 & 2. But like consumption, the inflation impulse in Scenario 2 is spread over a longer time horizon, and this has a smaller impact on the annualized rate of change. As a result, the Fed starts cutting rates a quarter earlier than in Scenario 1, but still considerably later than what’s assumed in our baseline forecast.

… but at the Wrong Time

In both scenarios, the fiscal stimulus adds meaningfully to economic growth, at a time when it really isn’t warranted. The stimulus checks issued during the pandemic came at a time of unprecedented economic uncertainty. While rising delinquencies, higher unemployment and slower wage growth all suggest that lower-and-middle-income households are coming under pressure, we’re nowhere near the levels of economic hardship felt during the pandemic. Imposing similar (or potentially even larger) stimulus measures to an economy that’s expected to run near potential and already has other sizeable fiscal stimulus in-tow runs the risk of unnecessarily stoking inflation. The timing could also reduce the efficacy of the stimulus. Traditionally, these types of measures come when interest rates are low and unemployment is elevated. But that’s not the case today. This increases the likelihood that a larger share of the stimulus is saved.

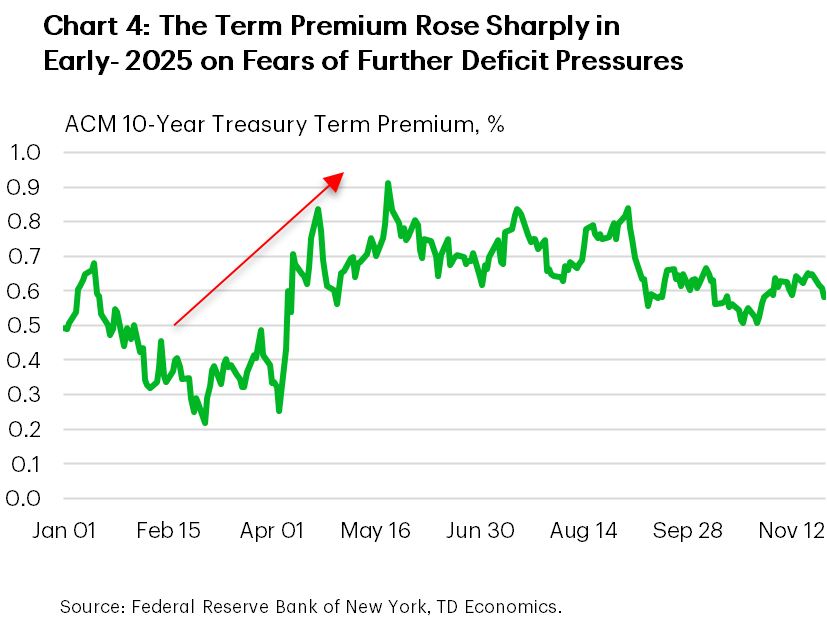

Should the tariff rebates ever come to fruition, there’s also potential for fireworks in the bond market. The term premium on 10-year Treasury yields moved meaningfully higher through the spring/summer when Congress was iterating on the OBBBA (Chart 4). At the time, market analysts were seeing the potential for a massive increase in federal government outlays without any meaningful offset in revenues. But since then, the administration’s use of tariffs has proven to be much wider in scope, unlocking a new income stream. While this helped to alleviate investor fears that the OBBBA would be entirely deficit financed, redirecting those tariff revenues to instead pay for additional spending could reignite fiscal concerns. This is particularly true should investors start to think that this isn’t necessarily a one-off occurrence.

At this point, we view this as a low probability event. As discussed above, there’s little appetite in Congress to pursue additional spending measures that will add to further deficit pressures. However, with ‘affordability’ having become a central pillar of the administration’s platform, it will be interesting to see what actions and policies are taken ahead of next year’s midterms.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: