U.S. Government Shutdown Risks:

2025 Edition

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: September 25, 2025

- Category:

- U.S.

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- The federal government will shutdown on October 1st if Congress is unable to reach an agreement to pass a continuing resolution before that date.

- The economic impacts of a short shutdown would likely be negligible, but negative effects would start to become visible if the shutdown were to last more than a few weeks.

- Financial markets have tended to exhibit muted reactions to shutdowns, but there is no assurance it will be calm seas ahead, especially under a prolonged shutdown.

As has become commonplace in recent years, the federal government is once again at risk of a shutdown to kick off the new fiscal year on October 1st. There is still time for an agreement to be reached in Congress, but the current deadlock in Congress warrants consideration for what would happen should an agreement not be reached by next Wednesday. Although the shutdown would affect roughly 25% of federal government spending, the ultimate impact will be a function of the shutdown’s duration.

However, even a short shutdown carries unique challenges for households, businesses, and financial markets, as the federal government ceases all non-essential functions. If policymakers are unable to reach an agreement in the first few weeks of the shutdown, the economic impact would likely become material. With midterm elections scheduled for next year, it seems unlikely that either political party will covet a prolonged shutdown. Nevertheless, majority margins are historically thin in Congress, which combined with an increasingly polarized political environment could narrow the scope for a timely resolution.

What is a Shutdown?

Before the start of every fiscal year on October 1st, Congress must pass twelve appropriation bills to fund the federal government’s discretionary spending. Mandatory spending, which covers 75% of total federal spending and includes large programs such as Medicare and Social Security, is not typically affected by the annual appropriations process.

Of the twelve bills that need to be passed this year, the House and Senate have each only managed to pass three, although the two chambers have primarily been acting separately (Table 1). In lieu of passing the twelve appropriation bills, Congress routinely makes use of continuing resolutions (CRs) as a stopgap measure. CRs extend current funding from the prior fiscal year for a specified period of time, typically for 6-8 weeks, although they have been used in the past to fund the federal government for the entire fiscal year (i.e. fiscal-year 2025). Passing a short-term CR is the current aim of Congress given the lack of time to pass the twelve funding bills prior to the October 1st deadline.

Table 1: 2025 Appropriation Status As of September 25, 2025

| Appropriation Bill | Passage by House | Passage by Senate | Final Passage |

| Agriculture | 8/1/2025 | ||

| Commerce, Justice, Science | |||

| Defense | 7/18/2025 | ||

| Energy & Water | 9/4/2025 | ||

| Financial Services | |||

| Homeland Security | |||

| Interior & Environment | |||

| Labor, HHS, Education | |||

| Legislative Branch | 8/1/2025 | ||

| Military Construction, VA | 6/25/2025 | 8/1/2025 | |

| State, Foreign Operations | |||

| Transportation, HUD |

State of Play in Congress

Congressional negotiations over fiscal-year 2026 appropriations have been slow-moving for some time, partly owing to the time expended on the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) over the summer. Progress remained limited leading up to the month-long August recess, at which time it became clear that Congress would require a CR to extend its appropriations timeline. While the necessity for a CR is agreed to by both parties, the duration and its inclusions are still being debated.

On September 19th a clean CR that would have funded the government through November 21st passed the House (217-212), but was rejected by the Senate later that day (44-48). Senate Democrats also put forward a proposal to fund the government through October 31st, with several additional provisions included, that was also voted down (47-45). Recall that 60 votes are required to pass most legislation in the Senate. The additional provisions included in the Democrats’ proposal were a permanent extension of expiring pandemic-era expansions of Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies, a reversal of OBBBA Medicaid cuts, and limits on the authority of the executive branch to withhold appropriations.

With no CR passed and the two sides remaining miles apart in negotiations, the risk of a shutdown on October 1st is growing. Both chambers are now recessed until next week for Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year), but House Speaker Mike Johnson recessed the House through to October 1st (after the funding deadline). The political play here is to force the Senate to adopt the clean CR passed by the House, but keeping the House out of session while the Senate returns on Monday could carry political risks. The situation remains highly fluid, with the President recently cancelling a Thursday meeting with the Senate and House Minority Leaders Schumer and Jeffries. Eleventh hour resolutions have been a staple of annual funding negotiations in recent years, but political posturing by both parties seems to suggest that the runway for such an agreement may be narrower this round.

Economic Implications of a Shutdown Barring a CR Agreement

Although Congress has come close to a shutdown several times in recent years, it has been nearly 7 years since the last shutdown occurred. This was also the longest shutdown on record, with the 35-day lapse in federal funding lasting from December 22nd, 2018 to January 25th, 2019. However, Congress had passed five of the twelve appropriation bills prior to the deadline, which limited the scope of the shutdown. Given the near certainty that no appropriation bill will be passed before October 1st, the impacts of a shutdown in the coming weeks could be greater depending on its ultimate duration. Some of this impact could be mitigated by making use of the funds allocated in the OBBBA, primarily in the areas of defense and immigration/border security, but the aggregate offset would likely be limited.

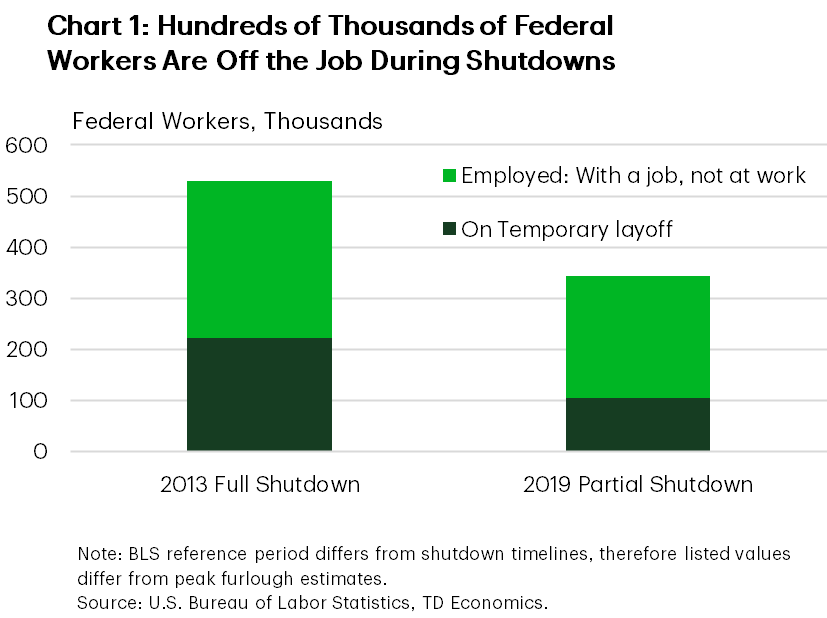

The most notable near-term impact would be the furlough of hundreds of thousands of federal workers (Chart 1). During the past two full government shutdowns (October 2013 and January 2018), roughly 800k federal employees were furloughed. This number typically declines over the course of a shutdown, as some federal agencies recall furloughed workers, though these workers remain unpaid. During past shutdowns this has included employees at the Departments of Defense, State, and Treasury.

Note that one possible difference of this shutdown is that the administration may seek to reduce the federal workforce in addition to furloughs. This was noted earlier this week in a memo circulated by the Office of Management & Budget, which directed agencies to consider reduction in force (RIF) notices for employees affected by the lapse in funding and for whose work is inconsistent with the President’s priorities. However, it also states that RIFs should be revised once FY2026 appropriations are allocated to “retain the minimal number of employees necessary to carry out statutory functions”. Assuming FY2026 appropriations do not substantially modify current statutory functions, this directive would be an extension of the administration’s ongoing workforce reduction efforts. However, it may increase uncertainty for the federal workforce both during and following the shutdown period.

Federal workers who are deemed to be essential (i.e. air traffic controllers, law enforcement, etc.) are required to work without pay during the shutdown. Fortunately for the federal workforce, the resolution of the last shutdown included legislation mandating backpay for all federal workers after a shutdown. This includes furloughed workers, meaning the federal government would be paying for unrendered services in this case. A report by the Office of Management & Budget estimated that the 16-day October 2013 shutdown cost the government $2.5 billion in pay and benefits for furloughed workers for hours not worked1.

In terms of economic data, furloughed federal workers would not show up in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data for non-farm payrolls, as they would still be considered employed in their measurements. However, it would be included in the agency’s household survey data, which is used to measure the unemployment rate. Historically shutdowns have not caused a spike in the unemployment rate, typically owing to the partial nature and/or brevity of the lapse in funding. The impact on the unemployment rate and other economic data series will remain unknown during the shutdown, as statistical agencies will cease publishing data. The data would be published once the shutdown ends, but if it were to extend for a prolonged period then this could raise risks for businesses that rely on the data as inputs to economic forecasts in addition to the Federal Reserve which relies on the timely publication of economic data to inform monetary policy decisions. In 2025, this could potentially amplify market volatility given elevated economic uncertainty, the central bank’s data dependence and the market’s aggressive pricing of rate cuts.

Outside of the labor market, the economic impact of a government shutdown tends to be nuanced. The halt in federal funding enters directly into the calculation of gross domestic product, but it also has indirect impacts on other sectors of the economy. The largest of which tends to be forgone consumption from the unpaid federal workforce, which by extension can also lead to higher delinquencies in the event of a prolonged shutdown. Private sector firms with federal contracts will also see disruptions, as non-essential agencies will be unable to award new contracts, obligate funds to existing contracts, or perform contract administrative functions. This could result in the cancellation of some federal contracts and private sector layoffs, both of which would further weigh on growth.

A host of other minor impediments to economic growth would be created by the lack of many federal government operations. Agencies that distribute loans and grants (Small Business Administration, National Institute of Health, etc.) would cease operations. Mortgage originations could be delayed if federal data cannot be verified due to furloughed personnel. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will continue to process tax filings but will be unable to issue tax refunds. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Food & Drug Administration (FDA) could cease or delay some inspections.

The CBO estimated that the last government shutdown in 2018/2019 reduced the level of real GDP by $11 billion2. According to CBO estimates, most of this lost economic output was recovered in subsequent quarters, but $3 billion was not. Studies have shown that shutdowns reduce annualized quarterly real GDP growth by up to 0.1 percentage-points for each week the shutdown lasts. However, the growth impact is typically assumed to be non-linear, meaning longer shutdowns lead to larger negative effects on growth. This underscores the necessity for a timely resolution of fiscal appropriation negotiations prior to October 1st or shortly thereafter.

Financial Markets & Government Shutdowns

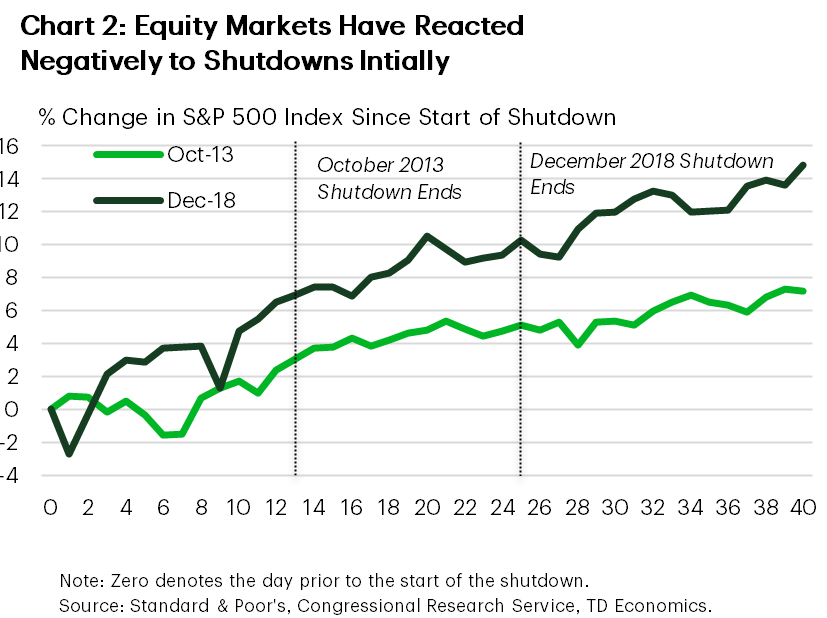

Given the brevity of the majority of past government shutdowns – most have lasted 3-4 days – financial markets have tended to look through the potential short-term risks to the economy. During two of the most recent government shutdowns in 2013 and even the more prolonged one in 2018/19, equity markets fell initially before recovering in advance of the resolution of the shutdown (Chart 2). At the end of the day, markets are driven by many factors outside of political developments.

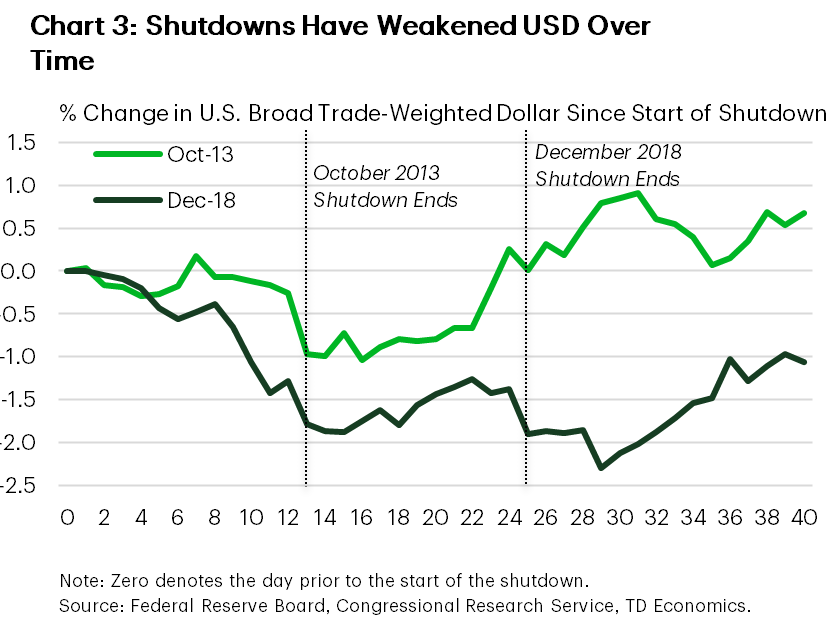

Turning to foreign exchange markets, the U.S. dollar only had a modestly negative reaction during the first few days of the October 2013 and December 2018 shutdowns (Chart 3). After that period, the dollar weakened moderately and remained below its pre-shutdown value for some time in both episodes. While the dollar returned to its pre-shutdown value within two weeks of the end of the October 2013 shutdown, it remained below its pre-shutdown value for two months after the end of the December 2018 shutdown. All else equal, this suggests that the higher political risks associated with longer shutdowns can have more lasting effects on financial markets.

Even if market reactions to shutdowns have been modest overall in the past, some risk factors this time around could potentially amplify moves. These include elevated equity valuations, a downtrend in the U.S. dollar related to policy volatility, and two recent U.S. credit rating downgrades in as many years. Combined with a data-dependent Fed that may soon lose access to said data, the potential for higher volatility in financial markets during a shutdown should not be discounted.

Bottom Line

If lawmakers can not reach an agreement to pass a CR in the coming days, the federal government will enter a shutdown for the first time in nearly 7 years. Assuming the shutdown is short-lived, the economic and financial market impacts are expected to be modest-to-negligible. If Congress is unable to reach an agreement over the near-term, resulting in a prolonged shutdown, then the impacts would be expected to become material. Ongoing negotiations remain slow but fluid, with the possibility for an averted shutdown still on the table. However, it is important to bear in mind that a CR would be a temporary resolution, and the risk of a shutdown would remain until either the twelve appropriation bills or a full-year CR is passed. Longer-term, the growing frequency of shutdown risks could pose further challenges to the financial standing of the U.S. government.

End Notes

- “Impacts and Costs of the Government Shutdown”, Office of Management & Budget.

- “The Effects of the Partial Shutdown Ending in January 2019”, Congressional Budget Office.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: