Market Insight:

Something’s Gotta Give

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: July 22, 2021

- Category:

- US

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: July 22, 2021

The fastest economic recovery in the modern era has already absorbed most of the economic slack caused by the pandemic. Businesses have responded with increased hiring and are trying to entice workers off the sidelines through higher compensation. Coupled with capacity constraints created by the stop-start nature of re-opening, this creates a recipe for near-term inflationary pressures. At the same time, the Federal Reserve has pulled forward the expected start of rate hikes and has indicated an intention to communicate to markets a plan to downshift asset purchases under its Quantitative Easing (QE) policy in the coming months. Though the combination of a hot economy, high inflation, and expectations for tighter monetary policy would usually result in rising bond yields, the opposite has happened. Over the last four months, the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield has declined from 1.74%, to a low of 1.19%. This begs the question: What gives?

The fastest economic recovery in the modern era has already absorbed most of the economic slack caused by the pandemic. Businesses have responded with increased hiring and are trying to entice workers off the sidelines through higher compensation. Coupled with capacity constraints created by the stop-start nature of re-opening, this creates a recipe for near-term inflationary pressures. At the same time, the Federal Reserve has pulled forward the expected start of rate hikes and has indicated an intention to communicate to markets a plan to downshift asset purchases under its Quantitative Easing (QE) policy in the coming months. Though the combination of a hot economy, high inflation, and expectations for tighter monetary policy would usually result in rising bond yields, the opposite has happened. Over the last four months, the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield has declined from 1.74%, to a low of 1.19%. This begs the question: What gives?

Sometimes we get used to greatness. Whether it’s rolling our eyes at seeing Tom Brady in yet another Super Bowl, or relishing when LeBron James gets ousted from the playoffs, appreciating greatness can sometimes lack stamina. The same goes for the pandemic’s economic recovery. This is the strongest recovery in generations. People, businesses, and governments have proven to be incredibly resilient. GDP growth in the U.S. is expected to return to its potential level this summer and the labor market is poised to return to full employment by this time next year. In past cycles, these feats have occurred with the passage of multiple years. With corporate profits surging and the stock market trading around all-time highs, this is the best outcome we could have hoped for against a backdrop that was exceptionally bleak last year.

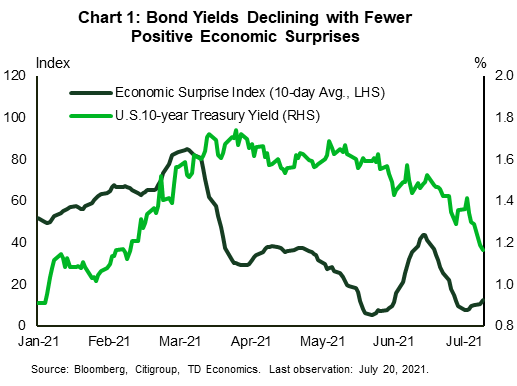

The issue with such great economic performance is that the bar for surpassing expectations has now been raised. This is apparent when we compare the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield against the economic surprise index (Chart 1). Economic data surprises peaked in late March, which corresponds to the peak in yields. Even though data have met, and often exceeded, high expectations, market participants are demanding more. This has some questioning whether an inflection point for growth momentum has already been reached in this business cycle.

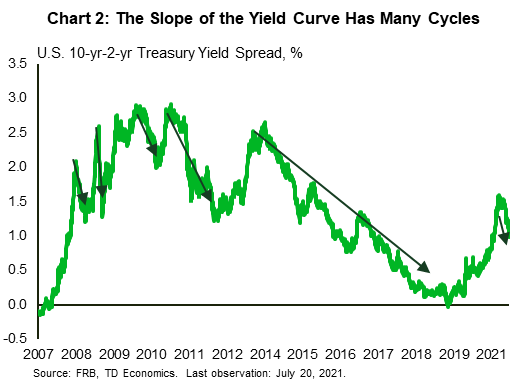

To substantiate this theory, some point to the flattening slope of the yield curve. The spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yield is a common barometer for the state of the economy. When the spread widens, usually in the early innings of a business cycle, this reflects optimism about the future. When the spread narrows, it usually signals the later innings and sometimes an impending recession. From August 2020 to March 2021, the spread jumped by 1.18%, to a high of 1.59%. But since that time, it has steadily narrowed, and now sits at roughly 1.1%.

Is this the beginning of the end? Not likely. First off, investors should expect volatility in yields, which in turn impacts the curve’s shape (Chart 2). During the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) period, we saw the yield curve spread shoot up by about 1.5%, to a high of 2.91% in the 15 months following the trough in the UST 10-year yield. But this wasn’t the end. Naturally, there were stops and starts along the road during the recovery, which caused the yield curve to trade in a wide range (1.72%) from 2008 until the Fed started hiking its policy rate in December 2015. In fact, there were five distinct yield curve cycles where the slope dropped by 0.9% or more. In the current cycle, we have had only one move of just 0.6%. Recent investor nervousness about the Delta variant of the virus and the uncertainty it injects into the outlook is an example of one of those stops along the yield-curve road in this cycle. This oscillating cycle in spreads isn’t signaling an end to the recovery, but is capturing the ebbs and flow of data and market sentiment that occurs within a recovery phase.

As the pandemic impact moves further into the rearview mirror, the path for yields will be driven by shifts in Fed policy. Our view is that by the end of the summer, the Fed will have seen enough evidence that the economy is on solid footing, prompting communication on its QE tapering strategy and schedule. Given that the Fed is trying to keep a lid on yields by creating excess demand for Treasury securities, the change in policy should open the door for a move up in yields. Recall that when the Fed hinted at a change to QE policy in 2013, the UST 10-year yield and the slope of the yield curve jumped over 1.3% and 1.2%, respectively, in less than a year.

We are also looking for the Fed to begin its rate hiking cycle by the end of 2022 and have the upper bound of the fed funds target reaching 2% by 2024. Comparatively, market pricing only expects the policy rate to reach a high of 1% by the end of 2031! Adjusting that for inflation expectations leaves a real policy rate that peaks at around negative 1%. We agree that the Fed is prepared to have the real policy rate significantly negative until the economy heals, but keeping it deeply entrenched over the next decade doesn’t hold water.

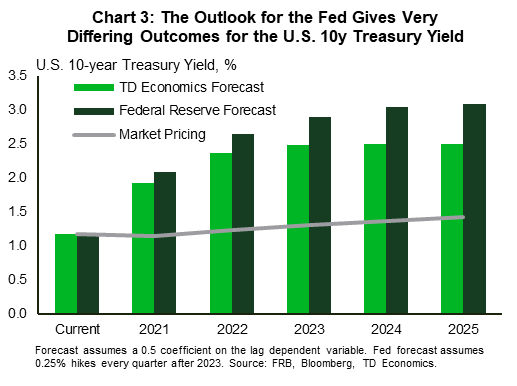

Let’s do a little comparative analysis. In Chart 3, we show the likely path of the UST 10-year yield under three scenarios: one using market pricing for the fed funds rate, one using the Fed median forecast, and one using the TD Economics forecast. Under the first scenario of market pricing, the nominal yield doesn’t ever even touch 2%. Under the Fed’s version, it would get there in 2021 and then rise towards 3% over the next couple of years. Our forecast has 2% as the end point for 2021, and an eventual peak of 2.5%. Given where market pricing sits for the Fed, there is significant upside risk for U.S. Treasury yields.

The wildcard for yields is inflation. Even though current inflation in the U.S. is very frothy (4% to 5%), market-based measures of inflation are pricing a reasonable outcome. The 10-year TIPS-implied inflation compensation is approximately 2.3%, after peaking at just above 2.5% in March. That’s not too far off our own long-term inflation forecast. This implies that the central bank has not lost market confidence in its ability to achieve its inflation mandate. It is also the reason why market pricing reveals a shallow path for the fed funds rate. As we mentioned above, this is where we see the biggest logic-gap in yields. This gap can widen even further if inflation comes in stronger than the Fed and market participants anticipate. In that case, we would expect markets to pull forward the timing of the Fed’s hiking cycle and a higher endpoint for the fed funds rate. Again, this creates significant upside risk for yields

In the meantime, the Fed is still in caution mode with respect to its policy signal, biding its time while it assesses the evolution of the virus and the impact on the economic data. All the while, market participants are waiting for the Fed to finally tip its hand towards tighter policy. There is a guessing game going on right now and the variability in the slope of the yield curve is a consequence. This leaves the market in an exploratory phase on data, while investors wait for direction from the Fed. We would only expect the slope of the yield curve to compress on a sustained basis once the rate hike cycle has commenced.

The economy is hot and near-term inflationary pressures are even hotter. Although economic growth is performing at a very high level, investors seem to want more. Pandemic-induced supply and demand factors behind much of the dislocation in prices can end up persisting longer than people are expecting, but so far, the predominant thought remains an easing of price pressures with time. The popular view is that the current 4% to 5% inflation rates will turn into 3% inflation by year-end, and settle around 2.5% by the end of 2022. However, that’s still nearly 1% higher than the average rate post-GFC, and as a result, marks a persistently higher inflation environment that should be captured in the compensation for longer term yields.

For the Fed, it is sticking to its guns, hoping that inflation will indeed come down to more comfortable levels. From our point of view, by the time supply-side impacts on inflation ease, the overall economy will have already wiped out all of the pandemic slack and the labor market will have reached full employment. The economy is driving in the fast lane. As the economic data continue to support this view, the Fed will get even more comfortable with the durability of the recovery even as the global economy navigates developments of virus variants in a post-vaccine world. This will enable the Fed to confidently taper its asset purchases in the coming months and rally around the idea of rate hikes starting in 2022.

Not doing so runs a greater risk. If the Fed is too cautious on tightening policy in 2022 and 2023, simple modelling exercises show an economy that pushes deep into excess demand and persistently higher inflation pressures. However, the bond market is priced to the perfection of a goldilocks outcome. It has inflation easing towards 2% at a time when the economy is deep into excess demand and, at the same time, it is pricing a Fed policy path holding at very loose levels into perpetuity. Either the current pricing for the Fed is too low relative to what they will do, or the Fed will be too cautious (like the market expects), causing inflation to rise more than expected. Both situations result in higher yields. Is there a possible way out of this conundrum? A persistent surge in productivity growth that permits stronger economic growth and controlled inflation outcomes could do the trick. Though this is possible, somehow we doubt markets are banking on this outcome. Something’s gotta give.

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.