Trade Makes Canadian Inflation Go Round

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: June 28, 2023

- Category:

- Canada

- Financial Markets

- Trade

Highlights

- The structural shift to bring global production closer to home will have a long-lasting effect on Canadian inflation.

- While global trade acted as a disinflationary force for many years, its influence has waned following the Global Financial Crisis. U.S.-China trade tensions, the pandemic, and Russia’s war in Ukraine have accelerated this trend.

- The Bank of Canada will no longer be able to count on trade to dampen price pressures, providing another reason for why nominal interest rates are likely to remain higher than in the past.

Global trade has been a deflationary force over the last four decades. The ability for firms to source goods from around the world has reduced costs across the value chain. However, the double-whammy of the global pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war has accelerated a recent trend towards bringing production back closer to shore. With this structural shift likely to have staying power, one important implication is that central banks will no longer be able to count on goods price disinflation over the long haul. This, in turn, underscores the likelihood that the equilibrium nominal interest rate is likely to remain higher in Canada and globally than in the past.

More Trade, Lower Prices

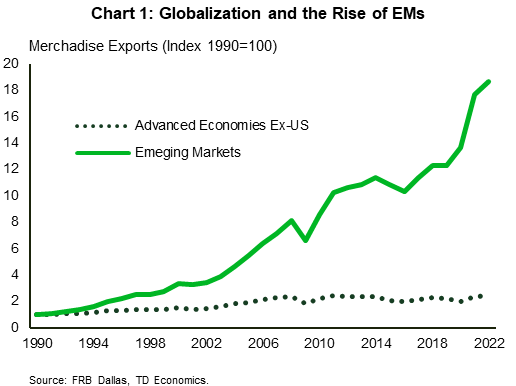

When is the last time you bought a product and the tag said, ‘Made in Canada’? It has probably been a while. Globalization has been on the rise ever since the double-digit inflationary episodes of the 1970s and 80s. The growth of Emerging Markets (EMs) and specifically China’s rise in the 2000s shifted supply chains toward lower cost producers (Chart 1). Global trade has increased the interconnectedness of economies around the world.

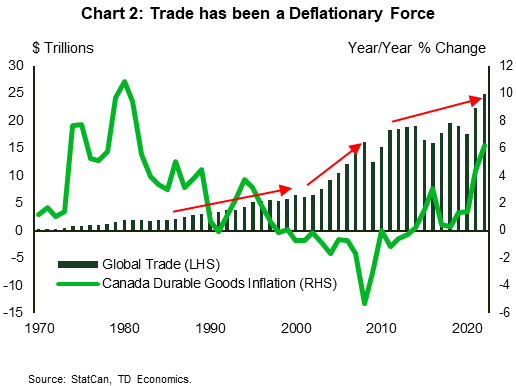

While the pandemic time-period renewed awareness about how commodity price and supply chain shocks can rapidly impact inflation, it is widely accepted that the diversification and integration of global trade starting in the 1990s had a prolonged impact on trend inflation. For years, researchers had been discussing the “Missing Inflation Puzzle” where goods inflation became disconnected from domestic economic fundamentals (wages). The deflationary impact of global trade played a major role, buttressed by falling inflation expectations and inflation targeting central banks (Chart 2).

The push amongst firms to find cheaper production alternatives benefitted Canadians’ wallets. Durable goods prices in Canada (e.g., furniture and appliances) fell by an average -0.5% annually from 2000 to 2019, while semi-durable goods (e.g., clothing and watches) averaged 0% growth over that time. The deflationary force was even greater in the U.S., with durable and semi-durable goods inflation averaging -0.9% annually. At the same time, services inflation consistently tracked well above 2% on both sides of the border. This corresponds with past research by the New York Fed, which showed that global trade lowered U.S. inflation by an average of 1.2% annually from 2000 to 2006.

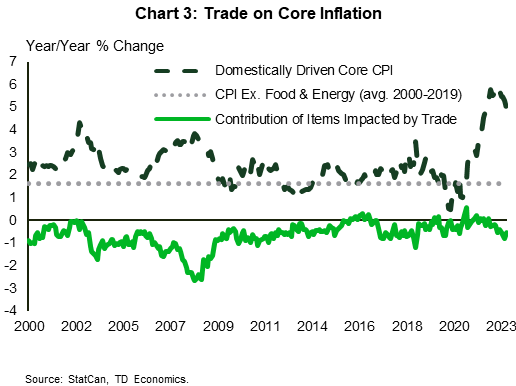

The deflationary force in goods prices caused Canadian core CPI (excluding food and energy) to consistently come in below the BoC’s 2% target over the 2000 – 2019 time-period. This begs the question: what would inflation have been without the growing influence of global trade? To do this, we built an index of core inflation that strips out products for which their prices are typically influenced by trade. We will call this ‘domestic core inflation’. This index reflects what core inflation could have been without the influence of global trade. Interestingly, while actual core inflation averaged 1.65% over 2000 – 2019, our domestic core inflation index consistently surpassed the 2% target, averaging 2.4% (Chart 3).

We also show that the peak influence of global trade on core inflation occurred before 2010 and has exhibited less of an impact since then. The growth of populist politics, which led to Brexit and the deterioration in U.S. - China trade tensions, were part of a broad trend to a more inward focus. The World Trade Organization reported that trade as a percent of world GDP declined to 56% last year, from a peak of 60% post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC). This trend is expected to continue and will emit less of a deflationary impact on Canadian inflation in the coming years.

A More Inward Future

Re-shoring. Onshoring. Friend-shoring. These are a few of the buzzwords that have been bandied around in reference to the desire for governments to reduce exposure to global production and vulnerable supply chains. The trend to a more local focus that started post-GFC is likely to have staying power. In the shorter run, cyclical forces are likely to win out, as a combination of higher interest rates, falling goods demand and easing global supply chain disruptions from the throes of the pandemic place particular downward pressure on goods prices. However, re-shaping global production to a new world trade order will require costly investment over the longer haul, especially when combined with that required to fund the green transition.

While the U.S. has been leading the way with its Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), advanced economies around the world are stepping up in a big way. And although Canada will benefit given strong trade ties with the U.S., since Budget 2021, the Canadian Federal Government has committed $139 billion to investment in the clean energy transition. The investment focus has become apparent with recent announcements in the auto industry, where Canada is now expected to be a major player in electric vehicle and battery production.

The shift in global production has many implications. There is the potential for a desynchronization in regional economic growth, hit to innovation, and reduced economies of scale and competitiveness. But one thing naturally follows and that is the potential for higher inflation. This will be on the radar of the Bank of Canada. Given its 2% inflation target, the removal of a deflationary force implies that nominal interest rates will stay higher over the long haul than otherwise would have been the case.

End Notes

- https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27663/w27663.pdf

- https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp02171.pdf

- https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/articles/2021/html/ecb.ebart202104_01~ae13f7fe4c.en.html

- https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr817.pdf?la=en

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: