Your Questions On The Russia-Ukraine Conflict

Date Published: March 1, 2022

- Category:

- Canada

- Trade

- Financial Markets

- What is SWIFT?

- What are the likely consequences for Russian banks that lose access?

- Why the reluctance to sanction all Russian banks?

- How effective will the central bank sanctions be?

- Can the measures create systemic financial instability risks?

- What's the historical precedence?

- How are financial markets reacting?

- What are the potential economic impacts?

- And what about Canada and the U.S.?

- What might become of the outward migration of Ukrainians?

Questions and Answers

What is SWIFT?

- SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) is a messaging system for financial transactions, not a payment settlement system. It does not transfer assets, hold funds or securities, or manage accounts. It was created in the 1970s by a group of international banks to facilitate cross border transactions between financial institutions. In 2021, SWIFT recorded an average of 42 million messages per day by more than 11,000 financial institutions from over 200 countries.

What are the likely consequences for Russian banks that lose access?

- Losing access to SWIFT would still make it possible for Russian banks to make cross-border transaction, but it would pose logistic challenges. Experience has shown that setting up alternative arrangements is time consuming and results in slower, less secure, and more costly transactions.

- Likewise, this can create a reluctance among foreign entities to enter into future contractual trade agreements. Impeding access to SWIFT adds to the layer of counterparty uncertainty. Last week, Bloomberg reported that at least two of China's largest state-owned banks were already restricting financing for the purchase of Russian commodities due to their risk assessment. The uncertainty related to SWIFT access since then would likely only amplify those concerns.

- When Iranian banks lost access to SWIFT, a group of EU countries designed a system to facilitate financial transactions for oil imports. The system was first proposed in early 2018 and didn't become operational until March 2020.

- Given that the cooperation on limiting access to SWIFT is at a much larger and coordinated global scale in this crisis, there would be few avenues for Russia to find work-around solutions, particularly when combined with broad sanctions.

- Russian banks (around 300 in total) represent about only 1.5% of SWIFT payment messages but the value of the transactions is estimated at half of Russia's annual GDP. Severing access of all Russian banks would have a major impact on international trade and financial transactions.

- A number of countries (EU, U.S., UK and Canada among others) have announced that "selected Russian banks" will be removed from the SWIFT messaging system, with details yet to be released.

Consolidated Positions on Residents of Russia

Source: BIS Consolidated Banking Statistics, TD Economics. As of Sept 2022 $US billions Share of total Foreign banks 121.5 Italy 25.3 20.8% France 25.2 20.7% Austria 17.5 14.4% United States 14.7 12.1% Japan 9.6 7.9% Germany 8.1 6.6% Netherlands 6.6 5.4% Switzerland 3.7 3.1% United Kingdom 3.0 2.5% Cross-border Positions of Russian Banks

Source: BIS Locational Banking Statistics, TD Economics. As of Sept 2021 $US billions Claims Liabilities Total 200.6 134.5 Banks 72.3 54.7 Non-banks 127.5 78.9 Non-bank financial 47.7 50.1 Non-financial 79.8 28.8 By currency Foreign currencies 172.2 62.8 US dollar 106.1 43.8 Euro 55.0 10.2 Swiss franc 1.7 1.1 Yen 0.3 0.2 Pound sterling 1.5 0.2 Other currencies 7.6 7.2 By instrument Loans and deposits 140.4 72.0 Debt securities 34.6 3.8

Why the reluctance to sanction all Russian banks?

- European leaders are concerned more comprehensive sanctions could hamper their ability to make financial transactions for critical commodity imports from Russia, particularly natural gas.

- Russia supplies about 40% of Europe's natural gas. Germany has notable exposure, where natural gas accounts for 25% of total energy consumption, of which 55% is imported from Russia.

- There are also strategic considerations. Sanctioning countries may prefer to target large, well-connected financial institutions to mitigate the economic fallout on the broad Russian civilian population.

- Western leaders are likely also concerned that weaponizing SWIFT will accelerate the development of alternative cross-border payment systems. There have been some developments along these lines. Following the sanctions imposed on Russian banks in 2014, its central bank created an alternative messaging system (SPFS) to process cross-border interbank transactions. However, only 20 foreign banks have joined to date. More recently, China's central bank created Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) which provides clearing and settlement services for cross-border renminbi payments.

How effective will the central bank sanctions be?

- Much of Russia's central bank reserves are held in accounts at institutions outside the country. The sanctions announced by the U.S., UK, EU, Canada, Singapore, South Korea, and other countries have essentially frozen these accounts, preventing Russia's central bank from accessing about one-third of its US$630 billion in foreign reserves.

- This constrains the ability of the central bank to support the ruble, which has come under intense pressure. In an effort to stem these pressures, the Russian authorities have put in place capital controls, including restricting non-residents from selling Russian securities and mandating Russian companies to sell foreign currency reserves. These measures are unlikely to stabilize the ruble. The last time the ruble faced such pressure in 2014, Russia deployed over US$80 billion of its reserves without success in providing stability.

Can the measures create systemic financial instability risks?

- Foreign bank exposures to Russia are concentrated in a few European countries and do not appear to pose broad global financial systemic risks.

- Foreign banks have a total of $121.5 billion in claims on Russian entities and residents, the majority of which are held by banks domiciled in Italy, France, Austria and the US.

What's the historical precedence?

- There are not many examples of where global coordination on sanctions of this scale have been applied, let alone the additional restraint on SWIFT access for banks. Below we outline the two experiences of Iran and Venezuela, with the caveat that neither of these countries carry the economic heft of Russia, particularly as a direct impact to a large region like Europe.

- In 2012, the U.S. and EU imposed an embargo on Iranian oil, banning transactions with the National Iranian Oil Company. Even before sanctions went into effect, international commercial banks were encouraged to stop interactions with Iran on the risk that they would be excluded from the global banking system. Despite the embargo, Iran continued to sell oil to China. Still, Iran's exports dropped from 2.5 million barrels per day to Europe and Asia, to under 1.4 billion barrels per day. This resulted in a 50% drop in export revenues between 2011 and 2013.

- In March 2012, the SWIFT system was cut off for the Central Bank of Iran and any Iranian bank or individual that had been blocked by the EU, crippling their ability to pay and receive payments for oil trade. The ban was widely seen as instrumental in bringing Iran to the negotiating table which led to the 2015 Iran-nuclear deal.

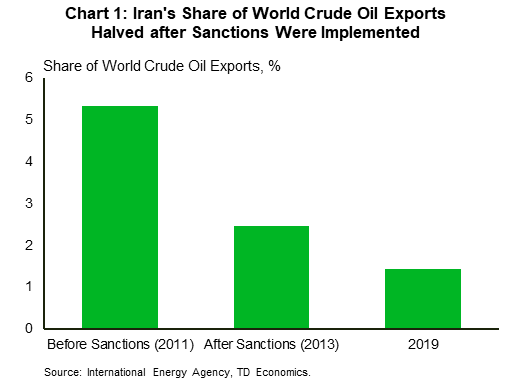

- These measures caused Iran’s share of global oil exports to be halved from 5.3% in 2011, to 2.5% in 2013 (Chart 1). In the two years following the lifting of most sanctions in 2016, Iran's oil output increased by more than 20%, but did not return to pre-2012 levels.

- Escalation of U.S. sanctions toward Venezuela started with Maduro's rise to power in 2013. In 2014, measures were applied to those individuals and entities involved in human rights violations, and Venezuela's access to sovereign debt markets and U.S. dollar financing. In 2019, more U.S. sanctions were imposed on Venezuela’s state oil company (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.), the central bank, and the government.

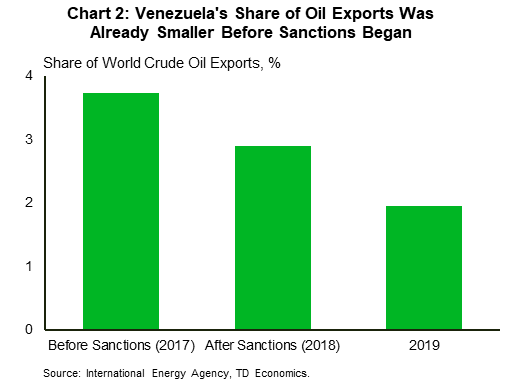

Venezuela's oil export revenue collapsed from $4.8 billion in 2018 to only $477 million in 2020. Its market share in global crude oil exports was already down from 5.2% in 2013 to 3.7% in 2017, but become a shadow of its former self at 2% by 2019 (Chart 2). There were no SWIFT sanctions implemented, but sanctioning

Venezuela's oil export revenue collapsed from $4.8 billion in 2018 to only $477 million in 2020. Its market share in global crude oil exports was already down from 5.2% in 2013 to 3.7% in 2017, but become a shadow of its former self at 2% by 2019 (Chart 2). There were no SWIFT sanctions implemented, but sanctioning - Venezuela's central bank created difficulty in clearing foreign transactions, making it reliant on barter trade with Russia, China and Iran.

- For Venezuela, prior to sanctions, oil exports were the thrust of growth, representing 35% of the economy in 2014. Historically, the economy and political backdrop stood on shacky legs with repeated bouts of high inflation and weak growth. But since the sanctions were enacted, the country has never recovered from the impacts, which include a massive devaluation of the currency and a draining of foreign reserves.

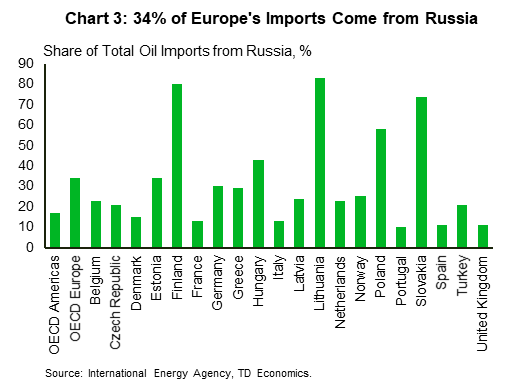

- At the time of writing, only Canada, whose share of oil imports is small, announced that it won't import Russian oil. A full embargo on Russian oil and gas imports in the world of tight energy supply would have greater implications for Russia and the rest of the world, than in the case of Iran and Venezuela. According to the International Energy Agency, Russia is the world’s third largest oil producer behind the United States and Saudi Arabia, producing 11.3 million barrels per day (as of January 2022). Russia is the world’s largest exporter of oil to global markets and the second largest crude oil exporter behind Saudi Arabia, exporting 7.8 million barrels per day, or roughly 12% of all oil exports. This is almost three times larger than the shares of Iran and Venezuela in the pre-sanction period. Roughly 60% of Russia’s oil exports go to OECD Europe, and another 20% to China (Chart 3).

- Europe's reliance on Russian natural gas is similar, with 32% of all EU and UK gas in 2021 coming from Russia. Transit flows via Ukraine accounted for over 25% of Russia’s pipeline deliveries to the EU and UK in 2021 (or roughly 8% of their combined gas demand). Ukraine also relies heavily on imported gas for its own domestic use.

- Russia has already been reducing its piped gas supplies to the EU market, and in the first seven weeks of 2022, deliveries were down by 37% year-on-year. To offset this, Europe has increased liquefied natural gas (LNG) inflows, with the U.S. accounting for more than half of the additional LNG since the beginning of the heating season. Nonetheless, EU gas storage levels remain roughly 28% below their 5-year average levels for this period of the year.

- This inter-dependence on energy supply between Russia and Europe is why many postulate that sanctions and the removal of SWIFT access will not apply to critical Russian suppliers. Some wonder if Russia will tactically cut energy exports as a retaliatory measure, but the flip side to that would be Russia's willingness to inhibit critical revenue flows that are needed to fund their military operations and other expenditures.

- The tit-for-tat tactics may yet unfold. Should Russia cut off Europe's gas supplies, some countries could face a critical shortage of energy for heating in the near-term, particularly in countries where natural gas storage is near record lows. Adaptive measures include switching gas plants to oil and curtailing the demand for energy more broadly. This could entail shutdowns in industrial production (indeed, some steel, aluminum, and silicone makers have already announced reduced production), as well as mandated shutdowns of non-critical industries.

- If Russia chose this avenue, there would be nothing further inhibiting Europe and the U.S. from sanctioning those remaining firms and removing the remaining banks from SWIFT access. In turn, this could limit Russian energy exports to other regions, like China, depending on the counterparty relationships of those countries with the U.S. and Europe. Russia companies are already a global hot-potato, and this would make them even more toxic to a foreign company wanting to trade with them, due to the high risk-exposure created by sanctions. For instance, there were reports that the Russian oil producer Surgutneftegas failed to award its spot tender for Urals crude, which suggests there is lack of appetite to buy Russian product, even though there were no official sanctions on Russian oil trade at that time.

Russia:

How are financial markets reacting?

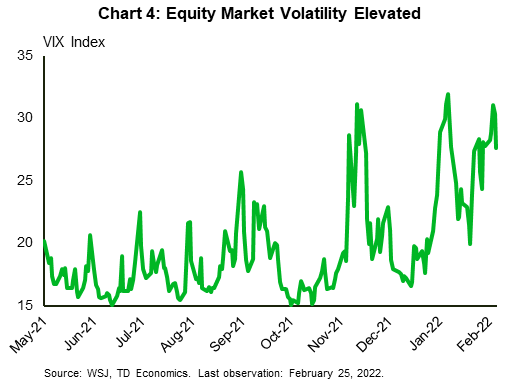

- In a statement of the obvious, equity markets have been volatile, as evidenced by intra-day price movements. On the day that Russia invaded Ukraine, the S&P 500 fell nearly 3% at the open of the market, but closed the day up 1.5%. This volatility was reflected in the VIX peaking at 37, more than double the level at the start of 2022. After all the swings, the equity market was still 9% lower than its 2022 peak.

- Bond markets have also been whipsawed, with the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield almost 30 basis points lower than the peak on February 15th. This move is partly flight-to-safety, but also an easing in Federal Reserve rate hike expectations. Previously, markets had the Fed hiking upwards of 6-7 times in 2022. Given the geopolitical risk, markets are now expecting five hikes. This has been our view all along, in a nod that caution needs to be exerted in raising rates too quickly, in order to gauge the lag effects on the economic indicators (see report). However, we maintained this view before Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and while we still think five hikes is the most likely outcome, it is predicated on a relatively short duration of geopolitical tensions. Risk sentiment would need to improve significantly by the end of the first quarter, otherwise the drag to economic growth will become more pronounced as time carries on (see report). If central banks in Canada and the U.S. start to show some concern that demand destruction could overtake the high price environment, the speed of interest rate adjustment or intention to hike would likewise be scaled back.

- Commodity markets have been a big story given Russia's raw material riches. Brent oil is above US$100 a barrel. Although it is down from its peak of more than $100, it remains around 12% higher in the last month. More strikingly, European natural gas prices are up over 35% in the last week, and more than five times the price prevailing last year.

- Big moves are also evident in agricultural commodities, where wheat prices were up 10% on Monday and 15% over the last week. Soybeans, lumber, and palm oil are also showing big gains over the last week.

- Even with all the volatility in global financial markets, it is the Russian market that is feeling the brunt. The Russian stock market has declined approximately 40% in the last three weeks, forcing the central bank to close its doors on Monday. Additionally, the Russian 10-year bond yield rose to approximately 13%, as the Central Bank of Russia hiked its policy rate to 20%, from 9.5%. Plus, the ruble is down nearly 40% since its peak in October and around 30% in the last week.

- The overall outlook for financial markets is fluid. An extended period of geopolitical strife is bad for trade and sentiment. We would expect a lengthy conflict would put further pressure on equities and push bond yields lower. Comparatively, we have seen many historical examples of how war puts downward pressure on risk assets. The 9/11 terrorist attacks (2001) and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait (1990) are two modern examples of conflict that induced double-digit sell-offs in equities. Given the sell-off we have seen to date, there is room for more pressure to come on risk assets.

What are the potential economic impacts?

- The current situation is replete with uncertainty. In a sign of how quickly the outlook is shifting, the rally late last week saw markets relieved that banning Russian banks from SWIFT was considered a no-go zone. However, over the weekend, momentum gained to not only limit access to SWIFT, but go even further and sanction the Central Bank of Russia. The latter wasn't even previously within scope among financial market participants.

- At the time of writing, details on sanctions and SWIFT exclusion were still unknown. But, many analysts are operating under the presumption that Russian entities will continue to be excluded from these measures that supply critical energy products to Europe. High energy prices and ongoing exports would offer some revenue stability and hard foreign currency to Russia, but it would be insufficient to offset significant negative impacts flowing from broad sanctions, a doubling in interest rates in the blink of an eye and the steep devaluation in the currency. The pain to Russia will be measurable and deep, with a recession within scope.

- And, that pain is likely to extend further. Policymakers in Europe and the U.S. have stated that the purpose of the sanctions is to impose long-term economic challenges. For instance, current developments have caused Europe to signal its intent to accelerate the pace of finding alternative energy sources to Russia. In a likely sign of things to come across the entire region, Germany has moved up its timetable to rely on 100% renewable energy by 2035. In an unusual twist, Russia's war campaign may have become a rally cry for faster ESG adoption, greater self-sufficiency and more strategic alignment to stable states that share Europe's core values. Even a truce between Ukraine and Russia at this point is unlikely to undo this sentiment.

- In the European Union, the sanctions will not be pain free. Our analysis last week centered on the transmission of shocks through risk sentiment and energy prices. In the scenario analysis, we assumed an even larger energy shock than is currently priced in markets. While Europe still manages to record positive growth (in the modelling exercise), the outcome ultimately comes down to duration. A persistence of elevated tensions and market risk-aversion beyond one quarter would likely inch the European region closer to a stagflation-style outcome within two-to-three quarters. And, the risk of an interruption in energy deliveries to the E.U. remains an ever present. Having said that, this risk begins to dissipate as spring approaches and the natural gas filling season affords some time to sort out deliveries ahead of the next winter season.

- Besides energy, the trade linkages between the E.U., Ukraine and Russia mean the effects of the conflict will be immediately felt. Volkswagen had already suspended production at two facilities due to the inability to secure components from Ukraine. Others will follow.

- However, much like when the pandemic first struck, the implementation of fiscal measures to blunt the economic impacts will be crucial. Catching headlines last weekend was Germany's announcement of a 100-billion-euro defense fund for 2022 (equivalent to 2.8% of 2021 GDP). Simply put, that's huge. To the extent this reflects net-new funds (rather than cut-backs in other areas), this capital expenditure will help cushion some of the economic blow.

- Moreover, member states had undertaken measures in the past year to help support households and businesses in offsetting higher energy costs, thereby preserving real incomes. Here, Italy is a notable example. Citing a smaller than expected deficit, it extended financial supports to consumers and businesses by committing six billion euros to help offset higher energy bills.

- Lastly, there is always a chance that OPEC may increase production to prevent demand destruction from high prices and/or to signal the reliability of the cartel as a political and economic partner. This, alongside the outlook for higher production in number of non-OPEC countries and renewed flows of Iranian exports, would help limit the upside to oil prices and blunt some of the negative economic consequences.

And what about Canada and the U.S.?

- Direct trade links with Russia and Ukraine are minimal. The main trade feed-through channel would be via a slowdown in Europe's economy back into North America. However, even here, the main trading partners are each other and Mexico – all relatively shielded from developments.

- As a result, we estimated previously that the primary economic impact would occur through the sentiment and commodity channels, with a modest negative impact imparted to both countries relative to our prior baseline. However, just like Europe, duration is the critical component that has yet to be determined.

- There are some buffers to consider. Higher energy and agriculture prices (i.e. wheat, potash), will impart a large positive revenue impact to a number of Canadian and American entities in that space. Likewise, particularly in the case of Canada, government revenues in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland & Labrador will bear the markings of higher inflows. Within the Canadian political environment, governments are more likely to offset some of the financial hardships to households and businesses with temporary supports, particularly those at the lower income threshold. It's less clear whether the U.S. political climate will permit the same, however both countries have significant excess savings that can offer a near-term cushion if risk sentiment improves in the coming weeks.

What might become of the outward migration of Ukrainians?

- The conflict is exacting a horrific human toll. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reports that more than 500 thousand people have fled Ukraine since last week and projects that 4 million people may ultimately look to escape the violence and destruction.

- Following the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, the E.U. developed a mechanism called the Temporary Protection Directive to handle large influxes of refugees. E.U. officials are currently discussing invoking the Directive for the first time in history.

- In short, it would establish a residency permit for the displaced person (of up to 3 years), access to employment, housing, social welfare, medical treatments, education for children and guarantees to access normal asylum procedures.

- Other countries are also either taking action or considering it. For example, the Canadian government announced that it would be prioritizing immigration applications for the people of Ukraine. In the U.K., family members of those who are British nationals or have been given settled status will be able to reside in there for 12 months

- Only about 10% of the roughly 700,000 Yugoslavian refugees that fled to Germany in the 1990s ultimately stayed. Still, longer-term solutions in the current crisis may be required if the situation in Ukraine remains too dangerous for families to return for some time.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.