Market Insight:

When I Find Myself In Times of Trouble

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: October 20, 2022

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Investors have flooded into the U.S. dollar, reflecting a prototypical safe haven flow that has occurred during every economic shock over the last four decades.

- The USD has seen its greatest strength against the currencies of other Advanced Economies due to a mix of energy import dependence, political uncertainty, and an overall inability for central banks to keep pace with the Fed.

- The Canadian dollar has also depreciated over the last few months, reflecting the vulnerability of Canadian households to rising rates, which will limit the BoC’s ability to raise rates as high as the Fed.

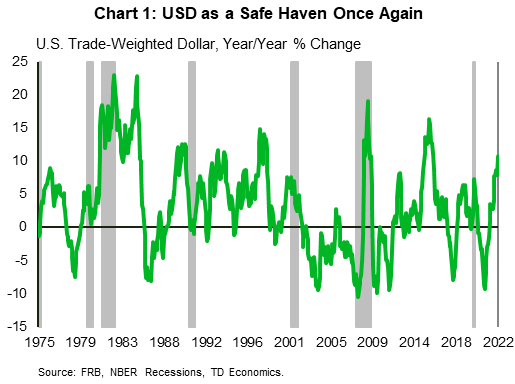

With the world economy sitting on a knife’s edge, volatility continues to cut into financial markets. Equities are in a bear market, bond yields are rising at a pace on par with the 1970/80s, and U.S. mortgage spreads are surging to levels last seen during the housing market crash of 2008. The current environment has left investors with few places to hide. But, there is one safe haven investors can count on: the U.S. dollar (Chart 1).

Over the last four decades, times of trouble have led to an impressive performance by the greenback – whether it be the 23% gain during the depths of the 2008 financial crisis or the 10% jump during the global pandemic. Once again, it’s speaking words of wisdom by gaining 16% since the summer of 2021.

The light that shines

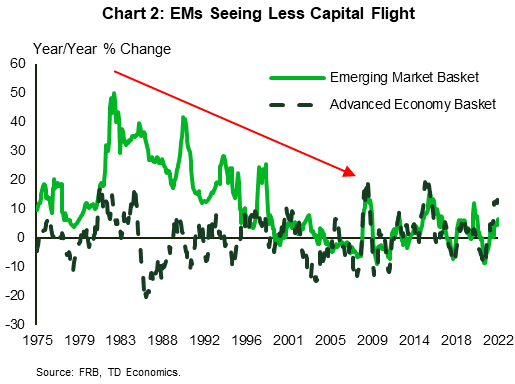

Economic shocks can quickly shift the investor mindset into protection mode. Risks are re-assessed, vulnerable assets are avoided, and safe ones come into favor. From the 1970s through the 1990s, Emerging Markets (EMs) were at the epicenter of various crises. The Latin American Debt Crisis of the 1980’s, the Mexican Crisis in 1994/95, and the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 being the most notable during the period. In all instances, investors sold vulnerable EM assets and bought U.S. Treasuries. This capital flight caused U.S. dollar (USD) appreciation, which had a compounding effect where the entire EM basket of currencies was depressed. (Chart 2).

But there was a change over the last two decades. China’s economic rise entrenched globalization and raised the standing of EMs, which now account for more than half of global GDP. Many EMs have amassed sizeable foreign exchange reserves, implemented flexible exchange rates, and reduced their foreign debt exposure. This has mitigated the threat of capital flight and has provided more foreign exchange stability. The impact of this change has been apparent over the last year. The USD has appreciated only 7% against the EM basket, compared to a 16% annual average gain over the last six U.S. recessions.

This relative currency outperformance of EMs also speaks to the current risks facing the global economy. Economies most exposed to Russia and/or energy imports are seeing significant currency depreciation, most of which are Advanced Economies (AE). And these are mostly Advance Economies (AE). The euro has dropped over 16% in the last year under a darkened economic outlook with the onset of Russia’s aggression on Ukraine. The fast-approaching winter months coupled with a quadrupling in Europe’s natural gas benchmark has heightened angst regarding whether the region will have to further scale back production and its basic need for heating.

In the same vein, the British pound is down around 19% over the last year. The UK’s dependence on purchasing energy in the spot market has left it vulnerable to global forces as a price taker. The nation is also dealing with homegrown problems. The impact of Brexit on investment and labor supply is a long-term negative that continues to lower the ceiling for the pound. And more recently, the shock of the government’s proposed mini-budget speaks to a level of political uncertainty that has further tested investor commitment to the region. Even though the government “walked back” that budget, the pound still carries the weight of political uncertainty.

The Japanese yen also makes the list of star underperformers, which is down close to 23% on the year. Japan too is an energy importer and rides the wave of oil prices. But this has not been the main influence on its currency. The Bank of Japan has been unwilling to adjust course on monetary policy, creating stark divergence with global peers. When nearly every central bank in the world is hiking interest rates, the BoJ is still implementing extraordinary monetary easing measures to prevent yields from rising. Japan has been through decades of deflation and doesn’t want to initiate another ill-fated policy error. However, yield hungry investors have little choice but to contrast a central bank that is keeping rates at the floor relative to the Federal Reserve that is marching rates towards 5%.

We can go on and on about the currencies that have depreciated against the USD, but there is a clear pattern. Relative to the U.S., global peers are more exposed to the various sources of economic shocks that are causing investors to pull out capital.

Canadian dollar trying to hold on

The Canadian dollar has held up pretty well relative to other major trading partners. Over the last year, the loonie is down roughly 11% versus the USD. This is significant, but overstates the negativity. On a trade-weighted basis, the CAD is down approximately 5%, and when we strip out the USD, the CAD is actually up nearly 1% this year. We think this more accurately depicts the risks facing the Canadian economy.

Over 2022, Canadian GDP growth has averaged more than 3% and total employment has stretched 2% above pre-pandemic levels. Elevated commodity prices are boosting corporate profits, government revenues, and employee compensation within a number of sectors. Stable income growth and resilient savings are buffering Canadians against high inflation, more so than stateside.

The strong economic backdrop has enabled the Bank of Canada (BoC) to confidently lift interest rates over 2022. Unlike other central banks, the BoC has moved in lockstep with the Fed. This, along side high commodity prices, have put a floor under the CAD relative to peers.

However, this is about to change. Markets are pricing a more aggressive path for the Federal Reserve relative to the Bank of Canada. The yield curve differentials are widening, with U.S. yields more than 30 basis points higher than the equivalent Canadian yields.

It’s not certain if this differential in market interest rate expectations will hold, but for now, it seems reasonable. Inflation in Canada has been slightly more cooperative, with the three month moving average of CPI moving from a peak of 12.5% annualized in May 2022, to 2.4% in September. This hints at further easing in year-on-year inflation going forward. This is also the case with core inflation, as monthly inflation rates have been decelerating for much of the last six months. If this persists, it opens the door for the BoC to pause its rate hike cycle ahead of the Federal Reserve.

The other reason it may do so is because Canadian households face asymmetric risks relative to their American counterparts due to higher indebtedness. Canada has roughly two times the reliance on real estate, has experienced a sharper correction, and has higher mortgage rollover risks than the U.S.

We estimate that by the end of next year, total debt servicing costs for households are projected to be 30% higher relative to 2022 Q1, with the average borrower spending an extra $2,500 per year on debt. The U.S. mortgage market mitigates this risk by a market structured to long term, fixed rate mortgages that do not renew on a five-year cycle, as in Canada.

As the global economy weakens, and the true impact of past rate hikes comes to bear on Canadian pocketbooks, we would not be surprised to see further weakness in the loonie over the next few months against the U.S. dollar. The currency will likely flirt with 70 U.S. cents if the Fed continues its solo mission to test the upper limit of rate hikes.

Bottom Line

The U.S. economy historically displays resilience to global peers when turmoil comes into scope. The environment should maintain the attractiveness of the dollar into early 2023, as markets assess the transmission of global risks on various countries.

However, as risks recede, become better understood, and positions in the USD become too weighty, repricing will again swing back toward peer currencies. We anticipate this timing is most likely around the middle of 2023. This is when we forecast the downturn in economic momentum will trough, as inflation moves decisively lower in the back half of the year. However, until there’s convincing evidence of this, investors will likely opt for the safety of the greenback.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.