Canadian Inflation:

The Long and Winding Road

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: September 7, 2022

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- The Bank of Canada (BoC) is set for another supersized rate hike this morning as it attempts to drive economic dynamics in order to cool inflationary pressures.

- Even with past aggressive rate hikes, reducing core inflation will be no easy task. Higher food and fuel prices have bled through to service sectors, which tend to have ‘stickier’ dynamics.

- The stopping point on the policy rate will come down to a communication exercise. The BoC has trained markets to prioritize data that is either lagged or represents the here-and-now, relative to the expected trajectory. Continuing to do so could lead to a higher end-point on the policy rate and a bigger hit to economic growth. A shift to guidance on “what to look for” within key metrics could help anchor inflation expectations and allow an earlier stopping point.

After a summer of hot inflation, the Bank of Canada is about to raise the policy rate into economically restrictive territory. A supersized rate hike is again expected, but financial markets have been oscillating between expectations of 50, 75 and even another 100 basis points amidst a central bank that has been unusually silent in offering guideposts since mid-July.

Regardless of today’s outcome, there is little question that the economy will reflect the weight of one of the fastest rate hike cycles in history. However, bringing price pressures back to the 2% target will be no easy task. There are signs that a peak in headline inflation has already arrived. That’s modest good news. The bad news is that the past surge in goods prices has bled into the service side of the economy, which is captured within core inflation metrics. Prices for services tend to be more sticky, raising the risk of an elongated period of high inflation.

For the Bank of Canada, this complicates an eventual needed pivot in rhetoric away from the here-and-now data to the most likely trajectory, given the known lags in the transmission of interest rates onto the real economy. Success around that pivot will make the difference in how deep the central bank will need to move into restrictive territory. An overnight rate of 4.0% (or higher) cannot be ruled out.

Once the policy rate peaks, we caution against expecting the BoC to be quick-fingered in lowering rates on any signs of a weak economy in 2023. Its priority will be to ensure that expectations remain anchored and that core inflation is on a clear path back to the target window.

The Core Problem

In the July CPI report, we were pleased to see the headline inflation figure drop to 7.6% year-on-year (y/y), from 8.1% in June, as gasoline prices subsided. This deceleration was a step in the right direction to bend the inflation curve, but it’s also the first step of many that are needed. The July inflation report captured a bending in international dynamics. In other words, we can break down inflation into two simple components to categorize the source of recent overshoots:

- Supply/externally driven factors

- Domestic driven factors

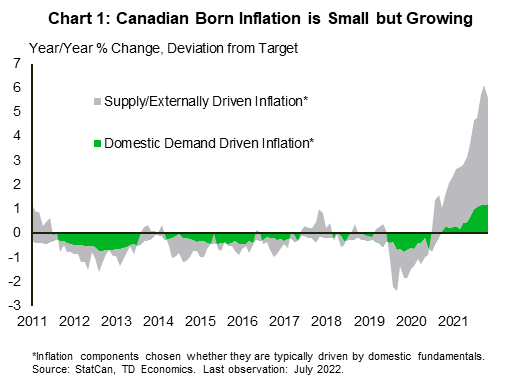

Most of the inflation miss over the last year has come from the first source (Chart 1). This dynamic is now reversing on a significant slowdown in global demand that is easing pressure on supply chains and commodity prices. These externally driven sources of inflation will continue to shrink in importance and pull down headline inflation.

While headline inflation is a barometer for the eventual direction of the core metrics, the timing and speed may vary significantly between the two. Holding the key to this is the responsiveness of domestic-driven inflation. As Chart 1 also shows, this component is holding firm due to a hot Canadian economy that is manifesting higher costs for mortgage rates, rents, restaurant services, entertainment, personal care and so forth. The end result is that all three of the Bank of Canada’s core inflation metrics are growing by at least 5% y/y.

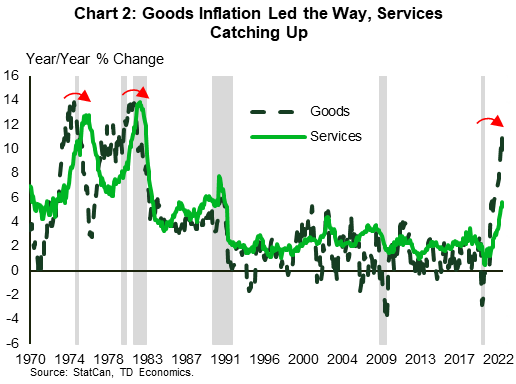

With domestically driven inflation becoming the main influencer, history helps show how price dynamics can unfold. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Canada was hit by a wave of food and fuel price increases, which drove overall goods inflation into double digits (Chart 2). This massive rise in goods inflation, which the central bank had little control over, squeezed the wallets of Canadians and ended up pushing the economy into recession on three separate occasions from 1975 to 1982. Those recessions coincided with a pull-back in commodity prices and a peak in goods inflation. However, services inflation kept rising and peaked more than a year later. This is because services inflation is much stickier. It takes longer to rise, but once it does, it can linger even in an economic downturn.

Of course, caution is always warranted in being too literal with historical comparisons. The central bank is acting more preemptively this time around, it has evolved its monetary policy approach over decades and is committed to a stated and transparent inflation target. At the same time, the structure of the economy has evolved in those 40 years. However, some things don’t change with time. High inflation has raised the cost of living and wages are responding. Since wages comprise a large component of service costs, it will take time for service inflation to cool. This tailwind is why we recently upgraded our inflation forecast over the remainder of 2022 and into early 2023.

What To Look For

For years central banks talked about how they’d prefer to fight rising inflation rather than deflation. They often pointed to historical examples of the effectiveness of interest rates in anchoring inflation expectations. But they appear to have underestimated the public’s tolerance and confidence once certain thresholds are crossed. There’s a big difference in psychology that comes with inflation being slightly above target, at say 4%, and being miles off the mark at say 7% to 8%. Taming inflation once it’s become overly distended from its anchor point is a different beast.

So what does this mean for the policy rate? That depends on how the central bank pivots in the coming weeks. It is currently boxed into a corner by training Bay Street and Main Street to focus on data that’s either lagging or in the here-and-now. This began as a side-effect from the pandemic, which led to more erratic movements in the data and larger forecasting errors. Those days are in the past and it’s time to get back to basics.

If the central bank’s rhetoric pivots to having greater confidence in the most likely trajectory for inflation in a year’s time, the near-term stopping point on the policy rate would likely be around 3.5%. This would allow the Bank of Canada to step aside to observe the lagged interaction between interest rates and the real economy.

However, our concern is that any pivot towards a pause could also de-anchor inflation expectations if markets build in stronger economic growth expectations. This is the hazard of having eyes trained on the here-and-now. A constrained ability to pivot in rhetoric and approach means that the policy rate could rise to 4.0% (and possibly higher) in order to provide a convincing stopping point, by crushing any hope that the economy will quickly regain momentum. This explains why some market pundits view a recession as the most likely path. The BoC faces a communication challenge in coordinating a policy rate to a soft landing. It may necessarily have to offer up a greater sacrifice of economic growth.

Unfortunately, whether or not the central bank is able to orchestrate a soft landing doesn’t detract from the point that the deceleration in the core metrics of inflation will lag. And this dynamic could also prevent an easing in monetary policy in 2023. Tackling inflation appears straightforward in theory, but not in execution. So buckle up, there’s a lot of ambiguity littering the road ahead.

The Bank of Canada’s reluctance to offer guidance in this rate-hike cycle was punctuated by Governor Macklem’s oped piece in mid-August that simply restated its mandate: “we know our job is not done yet — it won’t be done until inflation gets back to the two per cent target.” If they need to see the whites of the eyes that inflation is nearing 2% before communicating a pause, the lagging nature of the data suggests the odds of a recession would tilt above fifty per cent.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: