Highlights

- Under Trump’s proposed 10% across-the-board tariff (and assuming broad-based retaliation by Canada on U.S. imports), the Canadian economy would be hit hard. Real GDP would fall around 2.4 ppts over 2 years relative to baseline projections.

- That would likely be a worse case scenario as models often underestimate the mitigating impacts in the wake of a shock. For example, Canada’s retaliation approach would likely be targeted and strategic, while behavioural adjustments on the part of producers and consumers would help cushion the blow.

- We are optimistic that Canada will ultimately avoid blanket tariffs. The likelihood that tariffs drag down the U.S. economy, disrupt supply chains, and stoke inflation are enough of a reason to forgo tariffs on Canada.

- Ultimately, Trump’s best and most likely use of tariffs are as a bargaining chip to force Canada into concessions come the USMCA renegotiations in 2026.

The U.S. election is around the corner and it’s still anybody’s guess as to who will take the win. We recently published a piece that outlined the U.S. economic and fiscal implications of both presidential candidates’ platforms. In this report, we’ll focus specifically on what Trump’s tariff proposal – notably a 10% across-the-board levy on U.S. imports – could mean for Canada’s economy.

Given the nearly $3.6 billion worth of goods and services that flow across the Canada/U.S. border each day, there is little doubt that a tariff of that magnitude would deliver severe negative economic impacts on America’s northern neighbour. However, we build the case for why this “worst-case” scenario is unlikely to come to pass. Rather than a blanket tariff, a much more probable scenario in our view is one where Canada and U.S. successfully negotiate concessions in a forthcoming review of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2026.

Trade Linkages Are Vital

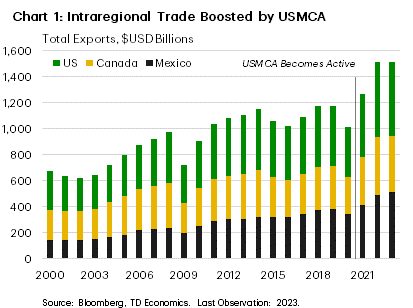

Importantly, the tariffs would hit Canadian (and Mexican) economies at a time of flourishing trade between the three countries, notwithstanding some lingering trade frictions. As of last year, total exports between Canada, U.S., and Mexico topped $1.5 trillion, nearly 30% higher than 2019 levels (Chart 1). Amid growing U.S.-China trade tensions, the passage of the USMCA in 2020–which Trump himself spearheaded during his first term in the Oval Office–has propelled Canada and Mexico to the top spots on the U.S.’ largest import partners list.

Further highlighting the importance of the trade relationship, over 75% of Canadian exports are currently destined for the U.S., a share that was last seen in 2006. Meanwhile, over 30 U.S. States have Canada as their number one export destination. Canadian energy exports to the U.S. have led the way, accounting for almost a third of its total merchandise exports. That share jumps to almost 50% when auto exports are included in the calculations. Canada also enjoys a healthy goods trade surplus with the U.S. at over 7% of GDP, mainly led by energy exports. The small surplus in exports outside of energy has also been on the rise since the implementation of the USMCA.

While Canada has maintained a relatively stable share of U.S. imports of around 13% in recent years, Mexico has seen its share rise steadily – from 13% in 2016 to over 15% last year. Mexico’s surplus with the U.S. currently stands at an elevated 17% of GDP.

The 10% Tariff Would Be a Hard Hit to Canada

In order to assess the impact of an across-the board tariff on Canada’s economy, we have incorporated the following assumptions:

- While a 20% tariff has subsequently been floated by Trump, we assume he sticks with his original proposal of a 10% tariff on all Canadian goods and services exports. Put another way, Canada does not receive an exemption.

- Canada retaliates with tariffs on all U.S. imports of a similar magnitude.

- Tariffs are phased in beginning early-2025 and removed by 2027 after what we believe will be a successful extension of the USMCA pact.

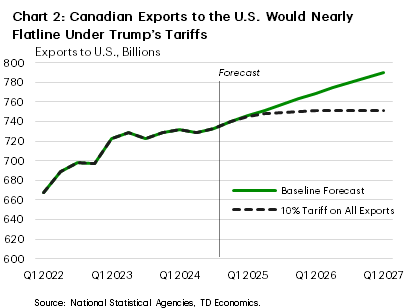

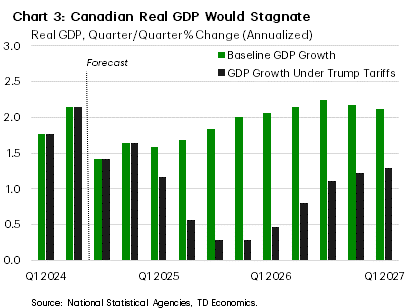

Our research shows that a full-scale implementation of the tariff plan could lead to a near-5% reduction in Canadian export volumes to the U.S. by early-2027, relative to our current baseline forecast (Chart 2). Retaliation by Canada would increase costs for domestic producers, and push import volumes lower in the process. Slowing import activity mitigates some of the negative net trade impact on total GDP enough to avoid a technical recession, but still produces a period of extended stagnation through 2025 and 2026 (Chart 3). The minimal increases are well below potential GDP and translate into output levels that are 2.4% lower by the end of 2026 compared to baseline estimates.

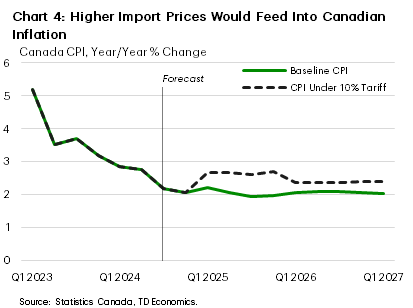

As the output gap widens, the Bank of Canada (BoC) may be forced into additional interest rate easing to the tune 50–75 basis point (bps), widening the spread to U.S. rates and putting downward pressure on the Canadian dollar. Tariffs create a negative income hit to Canadians as they pay more for imports, which would feed into a temporary and modest re-acceleration of inflation to the 2.5–3.0% y/y range before roughly reverting back to the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) 2% target by 2026 (Chart 4).

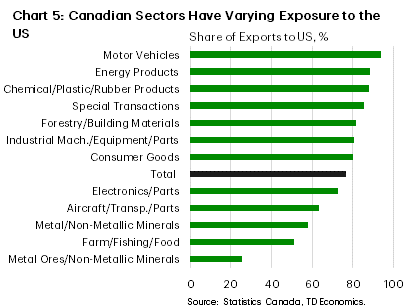

From an industry perspective, the auto sector would face the deepest negative impacts. The automotive supply chain is one of the most integrated and hardest to diversify away from, evidenced by the almost 20% of intermediary goods inputs that are sourced from the U.S. alone. Outside of autos, the energy sector, chemical/plastic/rubbers manufacturing, forestry products, and machinery have outsized exposure to the U.S. market (Chart 5). The metal ores and non-metallic minerals industries and agriculture sector are a little more insulated as only 25% and 50% of the industries’ exports, respectively, end up in the U.S.

Model-based Impacts Have Limitations

The steep impacts we’ve modelled are not out of line with those from other forecasters. Still, these results likely provide a worse-case scenario.

One key shortcoming of models is that they tend to underestimate the effect of behavioural adjustments that lessen impacts. In the face of tariffs, Canadian companies would likely adapt, source or develop new supply chains, while consumers would substitute products where possible. We don’t discount the potential for tariffs to be inflationary via price passthrough to consumers, but there is a high likelihood that Canadian producers would elect to absorb part of the tariff cost instead. The extent to which firms then absorb the hit to margins and substitutes are readily available, will go a long way in determining the final toll on real household incomes.

Moreover, should all of Canada’s goods and services exports to the U.S. be subject to tariffs, the country’s high degree of openness would allow for some level of import and export diversification. This will help to cushion the blow. In this scenario, trading partners like Mexico, the EU, and Japan will be key.

Lastly, Canada’s retaliation strategy would likely be targeted and strategic as opposed to braodly applied to all U.S. exports. This would mimic the actions taken in 2018 when Canada released a laundry list of consumer goods that would face a 10% tariff in addition to steel and aluminum tariffs. From whiskies to orange juice and lawn mowers to maple syrup, goods categories were carefully selected to inflict pain on Republican and swing states while protecting Canadian producers and consumers. Canada would likely first opt for a resolution to carve out an exemption from tariffs altogether, but a more strategic retaliation approach in the absent of this outcome will be top of mind.

Cooler Minds Will Probably Prevail

Beyond some of the model estimate pitfalls, we’re optimistic that Canada would ultimately avoid the fate of deep, across-the-board tariffs:

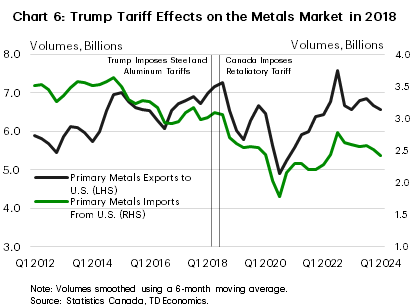

- Lessons learned from Trump’s first term – the former President frequently threatened tariffs on Canada during his previous stint in the Oval Office. His consideration of a 30% tariff on auto exports sent particular shockwaves. However, most threats did not come to pass, and those that did were more targeted than feared. Notably, the 25% tariff on steel and a 10% tariff on Canadian aluminum imports that were imposed in 2018 did have localized industry impacts but only modest macro effects. There was some scrambling by Canadian producers to adjust in the lead up to (and after) imposition of the levy, as evidenced by the declining trade volumes (Chart 6). Further, Canada responded with retaliatory tariffs on U.S. steel and aluminum imports. Ultimately, Canada would reach a deal with the U.S. to remove the tariffs in May 2019, almost a year after going into effect.

- Potential for big hit to U.S. economy and financial markets. Despite the rhetoric on the campaign trail around tariffs as a means to onshore jobs and grow the economy, we are hopeful that cooler minds would prevail. Notably, the overwhelming consensus among economists is steep tariffs, especially on Canada and Mexico, would lead to adverse near-term supply chain disruptions and inflict pain on U.S. businesses and households. We suspect that the former President wouldn’t tolerate a recession or major market shock on his watch, but the net effect of his policies could lead to just that. We’ve done extensive work looking at the economic and financial implications of a Trump presidency and conclude that relative to our baseline, a Republican Sweep is estimated to reduce real GDP growth by 1 percentage point from the tariff impact alone over Trump’s term. Tariff revenues under the plan would also fall well short of funding proposed tax cuts, adding an estimated $3.5T-4.0T to the deficit. That’s not to mention that the burden of the final tariffs is more likely than not to land on the American consumer.

USMCA Renegotiations Would Be Canada’s Ticket Out of Tariffs

Amidst all of the uncertainty around Trump’s policies, we believe the that most likely scenario is one where the U.S. administration seeks concessions under the pending USMCA review in 2026. The former President has acknowledged that tariffs can be an effective tool to secure better trade deals for the U.S. And, indeed, both Trump and Harris have already indicated that they would re-open the USMCA agreement, if elected.

The following are some high-priority areas that the U.S. will likely want Canada to move on:

Cracking Down on Chinese Trade Ties

Perhaps most critical on the list, Canada would be expected to enforce harsher trade governance with China. Options include, but are not limited to, emulating trade tariffs on China similar to the U.S., strengthening customs enforcements to prevent fraud, and tightening regulations on imports that employ forced Chinese labour. Canada must show the U.S. that they are willing to deepen economic partnerships through joint measures against trade with China. The Canadian government has already begun to take action recently via the 100% tariffs on imported Chinese EVs and a 25% tariff on various steel and aluminum products.

Concessions in this domain however, risks casting Canada further into the crosshairs of the U.S.-China trade war and has the most potential for economic consequences. The past has taught us that China is willing to impose retaliatory tariffs on Canada, as they did in 2019 when they banned the imports of Canadian canola and other goods. As a result, canola exports tanked by 70% and only recovered to 2018 levels as of last year. This means key agricultural and other goods sectors will remain at risk as Canada tries to appease U.S. requests. More recently, China initiated a one-year anti-dumping probe on the Canadian canola in response to the tariffs imposed on them.

Enforcing More Strict Rules Around Auto Production

Under the USMCA, a car or truck is exempt from tariffs if 75% of its components are manufactured in North America. Under NAFTA, the corresponding requirement had been only 62.5%. The goal of the increase was to encourage more manufacturing in the automobile sector to be domiciled in North America. At the time of signing, there was disagreement between U.S. and Canada (and Mexico) about how originating auto parts were calculated. The U.S. ultimately lost a legal dispute against Canada and Mexico, favouring the latter’s interpretation of what qualifies as regional value content (RVC) against the U.S.’ view that the calculation should be stricter. The U.S. will likely want to bring this issue back to the table in 2026.

Canada’s Supply Management System of Dairy and Poultry Farmers

In the 1970s, Canada implemented a system that uses production quotas and import tariffs as a way to protect the dairy and poultry industry. Canada did not abandon the management system when the original USMCA was signed, but they did make a commitment to enhance market access to the U.S. The U.S. has consistently alleged that Canada is improperly implementing the commitment. In the next round of negotiations, the U.S. is certain to revisit this by either demanding stricter enforcement of their current deal or requesting that the system be scrapped altogether. While these changes may induce localized impacts on Canada’s dairy and poultry industry, their macro effects would be minimal given it’s small contribution to total trade.

Digital Services Tax (DST)

Canada imposed a Digital Service Tax (DST) this year that taxes U.S. (and other foreign companies) 3% on revenue over $20mn from online services in Canada. The U.S. is already protesting the tax using USMCA’s dispute resolution mechanism. U.S. officials have also warned that if Canada keeps the tax in place, it could jeopardize renegotiation talks, so they’ll likely continue to press Canada on rescinding the tax.

Bottom Line

While we don’t rule out the possibility of steep U.S. tariffs on Canadian exports if the former President takes office, we believe that cooler minds will prevail. This reflects the importance of Canadian (and broader continental) trade to the U.S. economy – a relationship that was further nurtured by Trump’s signing of the USMCA during his first term. However, this is not to say that reaching a renewed USMCA deal will be without major potholes or smooth sailing.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: