Market Insight:

Stop, Recalibrate and Listen

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Director & Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: February 7, 2023

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- Financial markets have started 2023 on solid footing, with optimism that easing inflationary pressures raise the probability of a soft landing.

- Pressure on goods prices has been a catalyst and is likely to help anchor the quarterly annualized pace of total inflation at 3% by the summer and even lower by year-end. In turn, bets remain alive that the Fed will cut interest rates by the end of the year, or risk a harder landing with highly restrictive policy.

- The Bank of Canada’s earlier pause in the cycle is a nod to the high interest rate sensitivity of Canadian households. But, this means that getting-it-right is of even greater importance and what goes up, must come down.

The weather started off ice cold in 2023, but markets were hot. The S&P 500 jumped 7% in the first five weeks of the year, and bond yields came down 30 basis points. Financial markets are optimistic that subsiding inflationary pressures will ward off the conditions that could lead to a hard landing and usher in interest rate cuts by year-end – despite the protest coming from the central bank.

The inflation U-turn

U.S. consumer price inflation has peaked. It is now edging down the mountain under improved supplier delivery times, plummeting freight shipment costs, and lower energy and raw materials prices. As these influences snake through the production pipeline, consumers are starting to experience some of the benefits of price competition from high inventories amongst retailers.

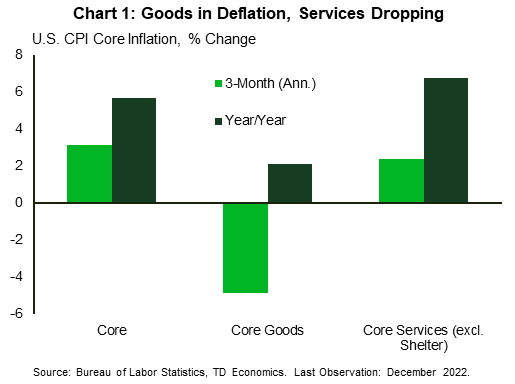

After two years of huge price increases, the near-term momentum of core goods prices has finally moved into deflation territory (Chart 1). Other preferred central bank inflation measures are also finally starting to crack. One of these crucial measures is core services excluding shelter, which strips out the lagging measure of rent inflation. As the year rolls forward and economic momentum slows under the weight of past rate hikes, it’s completely realistic that the quarterly annualized rate of inflation will break the 3% barrier by year-end.

A number of business cycle indicators are starting to show their age. The forward-looking ISM manufacturing index went from exuding strength to swiftly surpassing the contraction threshold. Declining expectations for new orders have businesses bracing for a revenue hit this year (Chart 2). Corporate spending intentions have already declined to the lowest level in three years.

Consumers are also worried. Sentiment measures are weak even with elevated job openings and strong wage growth. Surveys reveal that most people think the economy will be in recession in the next twelve months, raising the odds of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Consumers took a precautionary approach to spending in both November and December, despite rising inflation-adjusted income. It’s possible the first quarter of 2023 will show a modest contraction in consumer spending, which would mark a first since the height of the pandemic in 2020.

The Fed is talking tough, but can it hold on?

With 450 basis points of hikes in the rear-view mirror in the span of a single year, the Federal Reserve is starting to pivot in tone and action. Last week’s “old school” quarter-point adjustment in the policy rate (to 4.75%) led to a sigh of relief in equity markets. Whether or not the Fed pursues one or two more quarter-point adjustments is no longer the main event. The more relevant question is: how long will interest rates be held at this level?

When it comes to messaging, FOMC members have little choice but to show conviction in maintaining high interest rates for a long period. It’s the only remaining strategy to anchor inflation expectations and mitigate the degree of easing in financial conditions that naturally occurs once the peak threshold for the policy rate has been revealed. Because markets are forward looking, the next move that would be consistent with the weaker economic trajectory is already being anticipated. For instance, during the past four rate-hike cycles, yields on the 10-year Treasury declined by approximately 30 basis points two months before the policy rate had peaked, and a further 110 basis points before the central bank embarked on its first rate cut. Market behavior doesn’t look much different this time around.

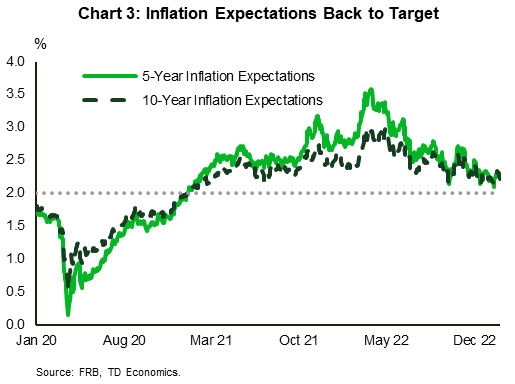

Approximately 100 bps in cuts are priced to occur by this time next year, which has been echoed by a 70 basis point decline in the 10-year Treasury yield in the past three months. Financial market participants already believe that the Fed will be successful in reclaiming the 2% inflation target (Chart 3). In turn, this market-conviction is the backdrop the central bank needs to have the leeway to throttle back the policy rate from highly restrictive territory as the year rolls forward.

However, until that moment, the Fed will keep talking tough on inflation to prevent too much easing in financial conditions relative to the current data and business cycle. Although interest rates on many credit products are tied to the prime rate (credit cards, lines of credit, and auto loans) will stay elevated and pinned to the policy rate, movement within the yield curve has already filtered through some areas of the economy. For instance, the BBB corporate yield has downshifted 120 bps, while the 30-year mortgage rate has dropped 100 bps. Little wonder that in its December minutes, Fed members said:

“Because monetary policy worked importantly through financial markets, an unwarranted easing in financial conditions, especially if driven by a misperception by the public of the Committee’s reaction function, would complicate the Committee’s effort to restore price stability.”

What’s behind the logic of a policy reversal?

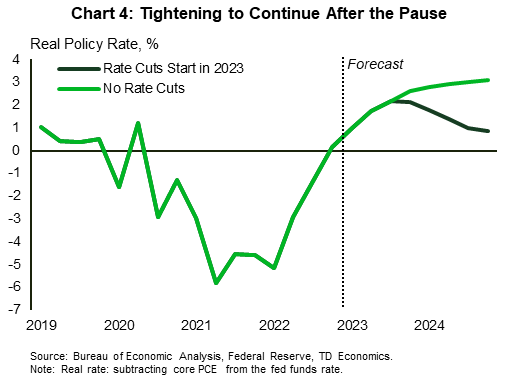

If you believe in the central bank’s December forecast trajectory for inflation and the economy, the real policy rate will steadily tighten, even after the Fed stops hiking (Chart 4). If left unchanged, the policy rate would drift too deeply into restrictive territory and become counterproductive to achieving the Fed’s preferred economic and inflation outcomes. In other words, the balance of risks tilt to undershooting the inflation target.

Analysts often cite the level of interest rates as the catalyst for a policy error, but we think it’s more about the duration that interest rates are left overly accommodative or restrictive. For instance, during the pandemic period, the central bank’s error on further stoking inflation wasn’t in placing the policy rate at the effective lower bound at the height of the economic crisis. It was in leaving it there for too long – eight quarters. Housing demand, consumer spending, government income supports to households, and inflation had long provided the proof points that the emergency-level on the policy rate was no longer necessary. This time, the central bank will be on the other side of this risk, of leaving rates too high for too long. Once a mindset is entrenched, be it high inflation or a hard economic landing, it eventually takes more work to break that psychology within business and consumer behavior. If the forecast evolves as we expect, we’re hoping that sometime within the third quarter of this year, the central bank rhetoric will shift, but not likely much before that point.

BoC hits pause, now what?

Turning to the Bank of Canada, there is no ambiguity that this central bank has hit the pause button after placing the policy rate at 4.50%. This speaks to the Bank’s confidence in the trajectory of inflation, but also the asymmetric risks among households when it comes to interest rate sensitivity.

In its accompanying forecast tables, the BoC expects inflation (CPI) to return to 3% by the summer and 2.6% by the end of this year. Given the Bank’s 1% to 3% inflation comfort range, this would mark success. However, similar to the Federal Reserve, if the real policy rate is left more than two percentage points above the estimated neutral level in a falling inflation environment, the economy will be unnecessarily absorbing too much financial tightening. A pause doesn’t mean the BoC can take its eyes off the road and just hit cruise control.

In the near term, the ‘conditionality’ of the pause means that the central bank could still tweak rates higher. But the burden of proof will be on inflation to be stickier than expected, and this would typically occur against a firmer economic backdrop. One area of concern is the strong connection between wages and inflation on services. The job market has yet to ease in any convincing or sustained manner. The blowout 69k job gains in December occurred against a still high 823k amount of available jobs. If the labour market remains tight, wages could be a roadblock on the way to 2% inflation. Herein lies the need for an economic slowdown.

Like the U.S., the growth transition is occurring in Canada. This is clearly reflected in real estate activity and in construction data – areas that are the first to respond to higher interest rates. Both have more than recalibrated from their pandemic-induced surge. The next stage occurs within confidence and the business production cycle. On this front, manufacturing output has already contracted in five of the past six months, while firms are beginning to pull back on inventory stocking. The final step is when companies moderate hiring, which can take the form of hiring freezes and/or outright staff reductions. This is the economic ‘stall’ that creates the sustained anchoring of inflation. And on this front, even Governor Macklem has stated that “a mild recession” could happen in 2023.

By extension, no central bank can afford to have a set-it-and-forget-it policy rate. What goes up in the near-term, must eventually come down. And given the greater interest rate sensitivity of Canadian households, the BoC needs to be even more careful than the Fed when it comes to keeping interest rates too high for too long. It is for this reason that we have the BoC cutting slightly more than the Fed in the latter half of this year.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.