Market Insight

Central Banks Getting Hawkish

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: November 2, 2021

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: November 2, 2021

The time has finally arrived. Central bankers have pivoted to a more hawkish tone, preparing markets for the inevitable – higher policy rates. Vaccines have supported domestic economic resilience in the face of COVID variants. Meanwhile, determination and stubbornness are highly regarded characteristics when it comes to economic progress. The same cannot be said when it comes to high inflation. This economic backdrop no longer warrants emergency-level monetary settings, pivoting central banks to speed up the timing of policy normalization.

The time has finally arrived. Central bankers have pivoted to a more hawkish tone, preparing markets for the inevitable – higher policy rates. Vaccines have supported domestic economic resilience in the face of COVID variants. Meanwhile, determination and stubbornness are highly regarded characteristics when it comes to economic progress. The same cannot be said when it comes to high inflation. This economic backdrop no longer warrants emergency-level monetary settings, pivoting central banks to speed up the timing of policy normalization.

Several central banks have already taken their first steps down this path. Some have lifted the policy rate, while others have ceased Quantitative Easing (QE, Table 1). The Bank of Canada (BoC) was the latest to join the ranks of those ending QE, providing it the flexibility to pursue rate hikes at any point in 2022. In contrast, the Federal Reserve’s more cautious approach will leave it lagging many of its peers, risking a greater overheating of inflation, should supply-side dislocations persist for longer than expected.

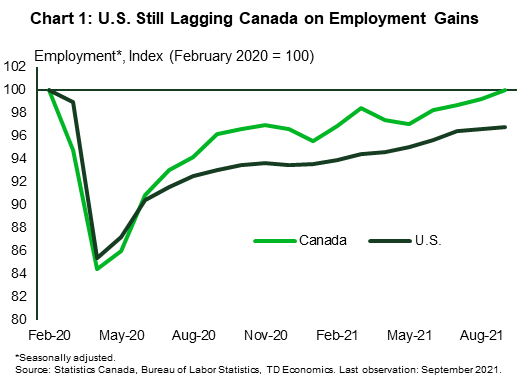

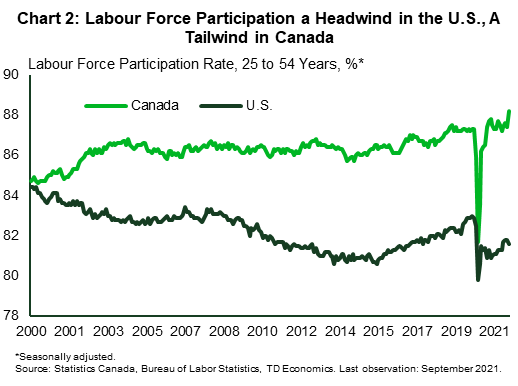

Why the difference in approach? Much comes down to labor market conditions. Countries like Canada have enjoyed a rapid return to pre-crisis job levels, while the U.S. continues to dig out (Chart 1). This better positions the recovery to be supported by wage and salary growth. When coupled with already-high levels of savings and wealth, Canada has a trifecta of strong domestic demand forces. Federal Reserve action has also been stymied by a slow recovery in labor force participation, whereas its northern neighbor does not face the same constraint (Chart 2). The Fed has a mandate to consider not just inflation outcomes, but also the broader progress of the labor market. The latter remains a diminished representation of its former self, which the Fed has interpreted as requiring more patience relative to other central banks.

| Already hiking | Getting ready to hike | Getting ready to cut QE |

| RBNZ | BoC | Fed |

| BoK | BoE | ECB |

| Norges | BoE | |

| Banxico | RBA |

However, since the Fed acts as the central banker to the world, erring on the side of too much patience could eventually lead to a faster rate-hike path. This would impart tremendous influence over global yields that may disrupt both the domestic and the broader global economy. Waiting to strike a perfect balance between inflation and labor market health is a risky proposition, and the Fed will have to settle for ‘good enough’.

The tapering of its balance sheet will commence in the coming weeks, allowing for an end to all net-new purchases in the first half of 2022. This will open the door for rate hikes in the months that follow. By the time the Fed ends QE, the economy will likely be in excess demand. In other words, transitory inflationary forces due to pandemic-related supply disruptions will be amplified by strong demand-side forces related to domestic fundamentals. A highly stimulative zero-policy environment, implemented in response to a crisis, will not be sufficient to counter these kind of demand-push dynamics. We anticipate that the Fed will be compelled to start its rate-hiking cycle in the summer of 2022, followed by one hike every three months until the policy rate reaches 2%. This course is not set in stone. If inflation proves sturdier and market expectations begin to reflect this paradigm, the timing and speed may be pulled forward.

Yields have been on an upward trajectory from exceptionally low levels since the end of September. We expect the U.S. 10-year yield to rise another 50 basis points to 2.0% over the next six months. This would return longer term yields to levels seen in the 2014-2017 period.

The notion of yields this high has caused some nail-biting among analysts who fret about weaker longer-term growth prospects. Some point to the compression in the UST 10-2 year spread as a cautionary signal. This angst is typical when markets must adjust to a new direction in central bank communication, but a flatter yield curve is a natural by-product of higher policy rate expectations. The current spread of 100 basis points is nowhere near levels that signal caution. In fact, this spread should continue to narrow to about 0.25% over the next two years. It’s important to bear in mind that having monetary policy set for 3-4% economic growth, when capacity can only accommodate 2% on a sustainable basis, can quickly create asymmetrical risks to inflation and asset prices. Those on the other side of the debate argue that the U.S. and other nations may already be staring down this barrel.

In Canada, the repricing of the yield curve is further along. The Bank of Canada has officially stopped all net-new bond purchases (eight months before the Fed) and has brought forward the date it believes the economy will have eliminated the remaining slack caused by the pandemic. This has led us to pencil in the first rate hike for April 2022, and we cannot dismiss the possibility the central bank will act earlier if the job market keeps surprising to the upside, as it did in September.

Investors are pushing up yields to reflect this outcome. Upon the BoC’s policy meeting last week, the Canadian 2-year yield temporarily jumped over 20 basis points in a matter of minutes. This reflected market participants pulling forward the first hike into the January/March period of next year and bracing for upwards of four more hikes over the remainder of 2022. While this pricing has since eased a little, the broader message is that market participants have a high degree of certainty that the BoC will be hiking ahead of the Federal Reserve, and by a greater amount over the course of the year.

Clients often challenge the notion that the BoC would (or should) hike ahead of the Federal Reserve. This is often grounded in the view that it risks too much of an appreciation of the loonie within an economy that’s heavily export-reliant on the U.S. for economic growth. And, since Canada has strong economic ties to the south, some question how the economic backdrop can differ sufficiently between the two countries to warrant an earlier rate-hike cycle.

Moving ahead of the Fed should not be interpreted as having a different monetary stance or direction. Both central banks will be raising rates next year, and the timing is a matter of nuances related to domestic conditions. Government policies and their economic support differ between the two countries, as do risks related to housing markets and household debt. Key aspects of recent Canadian economic data have surprised to the upside. The September labor report revealed a return of employment back to pre-pandemic levels, despite experiencing more economic strain than the U.S. during the Delta-wave. In all likelihood, Canada’s labor market will maintain stronger underpinnings relative to its U.S. counterpart, and, as we previously documented, this is not an unusual occurrence.

Then there’s the BoC’s Business Outlook Survey, which showed that business sentiment reached a new all-time high. The two drivers were record investment intentions and future hiring sentiment. This is a home run as far as any central bank is concerned. However, it comes with a cost. A record number of firms now expect inflation to hold above the Bank’s upper 3% threshold over the next two years. This is a red-flag. The BoC must respond to domestic inflation expectations. It cannot wait on the sidelines while the Federal Reserve takes a more patient approach in response to its own domestic conditions.

Along this vein, the BoC must also weigh its policy response against high levels of household debt and a stratospheric rise in residential real estate prices. Unlike the U.S., this is not a relatively new phenomenon exacerbated by the pandemic. Canadian consumer finances have been a concern for the past decade. High debt loads create more interest rate sensitivity, making it a better strategy to hike earlier and at a slower pace, than risk a later and faster cycle.

In addition, Canadian real estate demand and prices are incredibly stubborn and rarely respond to anything but higher interest rates. Over the 2016 to 2018 period, a number of macroprudential policies were at play, but the implementation of new policies to tap down demand proved temporary. It was only when the BoC executed an interest rate cycle of 125 basis points that it finally succeeded in cooling home price dynamics. The goal for the BoC is not to undermine the market, but rather to ensure monetary settings are set at a level where fundamentals prevail.

With the durability of the economic recovery and the persistence of high inflation, central bankers around the world are moving to reduce pandemic-driven monetary policy supports. The Fed will be among the laggards, but it will begin to taper its emergency QE program soon and create the opportunity to raise interest rates from emergency levels in the second half of 2022.

The Bank of Canada will not wait that long given that domestic conditions are not completely parallel to the U.S. It has already ended QE and is readying a hike in the first half of 2022. Both the BoC and the Fed are focused on employment gains, with the goal of closing in on maximum employment. But, threading the needle in an already elevated inflation environment could lead to a policy error. Central bankers are mindful that risks are two-sided. Hiking a little earlier and leaving sufficient time between policy decisions to monitor outcomes helps to mitigate the adverse impact of leaving policy rates too low for too long.

The yield curve will continue to respond as the months roll forward, putting upward pressure on a wide array of lending rates from corporate bond yields to individual mortgage rates. The time for patience on monetary policy is ending.

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.