Highlights

- Canada’s labour force has rebounded impressively since the pandemic shock of early 2020. There are now 0.7% more Canadians engaged in the labor force than there were prior to the pandemic.

- Jobs also eclipsed their pre-recession level in September, but with the pace of hiring outstripped by that of the labour force, the unemployment rate (at 6.9%) is still well above its pre-crisis level of 5.6%.

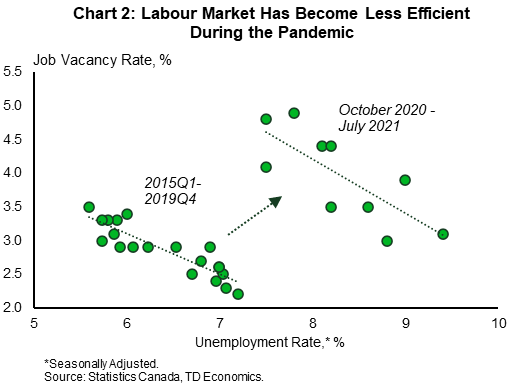

- At the same time, growth in demand for workers has risen faster than hiring, leading to increased vacancies. In July – the latest data available – the vacancy rate hit 4.8%. Based on the relationship between job vacancies and unemployment that existed prior to the pandemic, the job vacancy rate in July would be consistent with an unemployment rate roughly half of what it is today.

- Increased labor market frictions have made it more difficult to match the unemployed with job vacancies. Health concerns are high on this list. While these should dissipate, others, including an increase in long-term unemployment, are likely to prove longer lasting.

- The mismatch between labor demand and supply is particularly acute in sectors most highly impacted by the pandemic, with accommodation and food services the poster child. These sectors are likely to see stronger wage growth in the months ahead until they move closer to balance.

Over the past year, Canadian workers have been flooding back to the labour force. As of September 2021, there were 0.7% more Canadians engaged in the labour market than there were prior to the pandemic. This contrasts to the experience in the United States, where the labor force is still 2.0% below its pre-pandemic level.

As people have returned to the workforce, the jobless rate has remained relatively elevated. While the number of Canadians employed has also eclipsed its pre-recession level, gains in hiring have fallen somewhat short of the rebound in the labour force. As at September, the unemployment rate stood at 6.9%, or well above the trough of 5.6% hit in January 2020.

At the same time, measures of employer demand for workers have grown much more rapidly than actual hiring to the point where business concerns around labour shortages have reached a high pitch. According to the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses’ Business Barometer, shortages of skilled and unskilled workers have replaced insufficient demand as the main factor limiting firms’ ability to increase sales or production (Chart 1). This may seem puzzling given the healthy number of Canadians available and searching for work.

This incongruency likely reflects a myriad number of factors that have kept the unemployed from filling available positions. These include ongoing health concerns – especially within high-contact occupations – government income supports, less reliable childcare, and broader changes in the nature of work brought about by the pandemic. Much of the mismatch is concentrated in industries heavily impacted by the pandemic. Most other pockets of the job market appear to have achieved a better balance between labour demand and supply.

Despite rising evidence of labor shortages, wage growth has stayed relatively subdued in Canada. It is likely to pick up. The reallocative nature of the economic shock is already evident in stubbornly high long-term unemployment that will make it more difficult to fill positions in rebounding industries. This development – combined with a strong cyclical labor market recovery – is likely to increase the bargaining power of workers and put upward pressure on wages in the quarters ahead.

Pandemic Creating Frictions in Labour Market

Relative to the pre-pandemic period, the disconnect between labour supply and demand points to greater inefficiencies in Canada’s labour market. The pandemic has introduced “frictions” that are gumming up the labour matching process. This is reflected in a rightward shift in the relationship between unemployment and job vacancies – known as the Beveridge curve. As such, the unemployment rate today is much higher than what would have been predicted by the job vacancy rate in the period from 2015 through 2019, indicating that openings are not being filled as smoothly or quickly as they were prior to the health crisis (Chart 2).

There are several likely explanations for the increased mismatch in labour demand and supply over the past year:

- Ongoing Health Concerns

- Fiscal Support Programs

- Lack of Childcare

- Occupation Switching

- Increase in Long-term Unemployment

The pandemic has increased the risk of going to work, especially in occupations that require high personal contact. Throughout much of last year, vaccines were not yet available to large segments of the population. Even as vaccines were rolled out, Canada endured harsh second and third waves of the pandemic where health worries remained top of mind. So, while Canadians have remained engaged with the job market to a much greater degree than stateside, ongoing health concerns have led to increased hesitancy to apply to many types of jobs that couldn’t be performed from home.

As the pandemic shock hit, freshly-minted government income support programs offset losses in pay. The Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which ran until early October 2020, enhanced employment insurance, the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), and other income supports, provided around $2,000 per month, helping those without work cover regular expenses.1 For some Canadians, benefits exceeded what they made in their previous jobs.

Most of these programs were extended in the spring until late-October this year, although at a lower benefit rate. These supports were vital early on in the pandemic given widespread lockdowns holding down job availability. Benefit recipients must look for work and accept it where it is reasonable to do so, but given the ongoing health concerns noted above, many Canadians may have reduced the urgency to job search, especially in higher-risk areas.

Another aspect of the pandemic that has created frictions in the labour market is less reliable childcare. Schools and daycares were closed through much of the health crisis, resulting in new challenges for parents. Even with new job opportunities available, parents may not have been able to take them. This impact has likely faded as schools and daycares have reopened, but even now, potential outbreaks could result in children being sent home.

The health crisis has led many Canadians to rethink their careers. According to a survey by Morneau Shepell, nearly a quarter of respondents said they considered an occupation or career change because of the pandemic. Anecdotal reports indicate that workers in heavily-impacted industries were the most likely to switch. So, as restrictions were lifted and businesses in these sectors rushed to boost staffing levels, fewer workers were to be found.

An increase in the number of people unemployed for an extended period of time increases the risk that they will be unable to immediately return to the workforce in the same capacity that they left. The number of workers who have been unemployed for over a year has risen 2.5 times relative to the pre-pandemic period. This could prove a more persistent labour market friction.

A Few Industries Making Outsized Contributions to Labour Market Imbalances

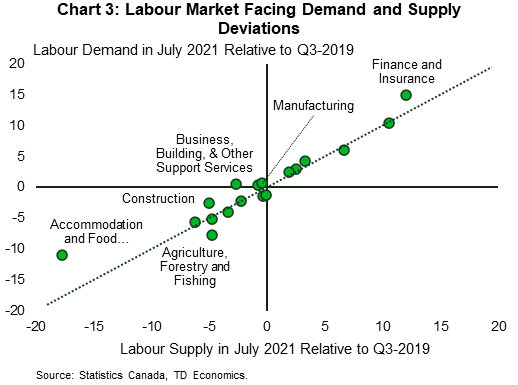

Delving into sectoral level trends offers further insights into current labour market imbalances. Chart 3 shows labour demand (the sum of vacancies and employment), and labour supply (labour force) in July 2021 relative to their levels in the third quarter of 2019 for each industry.2 The 45° line indicates whether labour demand and supply are similar to what they were prior to the pandemic, which was a period we can justifiably label as “balanced”. If an industry is above this line, labour demand growth has exceeded supply, and vice versa if its below.

As of July, labour markets in most industries appeared to be in balanced territory. For 13 of the 18 industries, covering 75% of total employment in Canada, the gap between labour demand and supply was only around one percentage point. This suggests that labour market frictions brought on by the pandemic have not significantly impacted the majority of industries.

That said, there are the few that are making outsized contributions to labour market imbalances. Accommodation and food services stands out as the industry with the greatest labour discrepancy compared to 2019 levels, with labour supply down much more than demand as of July.

The finance and insurance industry is another area with substantial mismatch between labour demand and supply. Like accommodation and food services, labour market conditions have tightened with labour demand up more than supply. It’s noteworthy that both have increased from pre-pandemic levels as hot real estate and financial market activity allowed for solid gains through the health crisis. Currently, tight labour conditions could be due to a shortage of available workers with appropriate skillsets.

On the opposite end, industries such as agriculture, forestry and fishing, and wholesale trade have seen demand fall more than supply relative to late 2019. The former has been on a several-decade downward trend that was worsened by the pandemic and more recently by extreme weather events, while the latter has been impacted by the lifting of public health restrictions which has led to some reorientation of consumer spending from goods back to services.

Wage Pressures Likely to Increase Where Shortages Are Most Evident

Labour market imbalances have implications for wages. Faced with staffing shortages, firms may be left with little choice but to increase pay to attract new workers. Currently, wage growth is relatively subdued, reflecting the fact that labour markets are roughly balanced across most sectors. Indeed, fixed-weighted average hourly wage growth over a two-year period (which accounts for employment composition effects and pandemic impacts) slowed to 2.3% annualized in September from 3.4% in January.

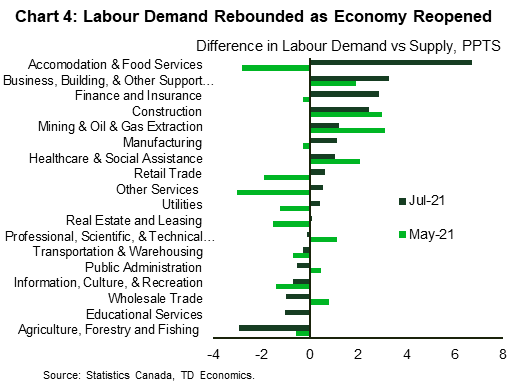

However, demand-supply imbalances have been becoming more prominent and widespread since the late spring as provincial economies reopened. From May to July this year, 10 of the 18 industries saw labour demand grow faster than supply (Chart 4). For eight of these industries, this resulted in a wider positive gap between demand and supply. It may be with a lag, but growing labour market imbalances are likely to boost wages in the coming months.

Unsurprisingly, the heat is in sectors which have made outsized contribution to labour market imbalances. The accommodation and food services industry tops the list followed by business, building and other supports and the finance and insurance industry.

For some sectors, labour imbalances have eased to some degree since May, but labour demand continues to outpace supply. These include construction, mining and oil and gas extraction, and healthcare and social assistance industries. Businesses operating in these sectors may still have to raise pay to meet staffing requirements.

At the same time, other sectors have seen labour conditions loosen recently. As noted previously, extreme heat and drought conditions constrained agricultural output in July, contributing to a decline in demand in agricultural workers. Meanwhile, cooling building activity in recent months, particularly less demand for home renovation goods, weakened labour conditions in the wholesale trade sector.

The chart also shows a widening negative gap between labour demand and supply in educational services, but this could be an artefact of residual seasonality in the data as July typically sees a substantial drop in education workers. The restart of schools in September likely tightened the labour market in this sector.

Long-term Unemployed Likely to Be Slower to Enter Employment

It’s quite possible that some of these wage pressures moderated in August and September. Canadian employers managed to ramp up hiring by close to 250k jobs during these two months. In September, much of the increase in employment came from the ranks of people formerly out of the workforce entirely. On the other hand, high-frequency data show continued growth in job postings.3 This points to robust labour demand, which could eventually move wage growth higher.

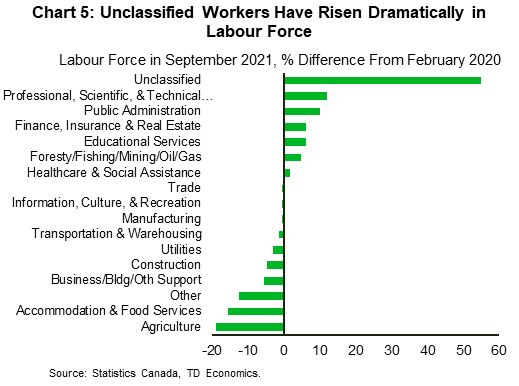

There could be some moderation in pay pressures if workers who were without work for a long time fill more of these openings. As of September, there were nearly 250k Canadians who were unemployed for over a year. These workers have not been included in the prior labour supply-demand analysis as they are placed into the “unclassified” category by Statistics Canada due to the fact they last worked over a year ago (Chart 5). Presumably, many of these individuals were last employed in sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, such as accommodation and food, building support, and other services, where labour supply remains below pre-pandemic levels, but worker demand has since rebounded. With in-person school restarting, and income supports expiring (if the government does not extend them as recent reports suggest), some of these longer-term unclassified workers could well return to work in these industries.

Having said that, the pandemic has imposed a reallocative shock that could complicate this story line. Being unemployed for an extended period may have led to desired career changes, a common occurrence during the pandemic. Just as important, being without work could have deteriorated skills, making it difficult for workers to pick up where they left off. Similarly, once businesses in an industry meet staffing requirements, unemployed workers may have to re-skill to find jobs elsewhere. These factors would prolong labour market frictions and keep long-term unemployment elevated. This suggests that wage pressures will build, at least until these imbalances are resolved.

Wage Growth Likely To Pick Up in Coming Months

The Canadian labour market has made strides recently, with employment moving above pre-pandemic levels in September. Still, given the increase in job vacancies, gains could have been even stronger if not for unresolved frictions within the labour market. These issues are most apparent in a few industries where the misalignment between worker demand and supply is most significant.

In the near-term, unemployed workers filling available positions could ease some of the labor shortages. But, career changes, deterioration of skills and/or skills mismatches could keep longer term unemployment elevated, thereby prolonging them. This would add to the pressure on wage growth.

Indeed, wage growth is likely to pick up in the coming months due to the incongruencies caused by the health crisis, with industries facing the steepest labour market imbalances seeing larger gains in employee compensation. Even as the factors causing these dislocations fade, the economy is projected to get closer to full employment in 2022, thereby broadening wage pressures across other industries. Higher consumer price inflation, brought on by supply chain disruptions and higher commodity prices, may also lead to employers making above average cost of living adjustments to salaries. Taken together, stronger wage growth is on the horizon for Canada.

End Notes

- Other benefit programs include the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit and Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit.

- July is the latest data point available. We compare against 2019Q3 levels as this controls for seasonal effects since the vacancy data are not seasonally adjusted and are only available on a quarterly basis prior to 2020.See

- Job postings from the job search website, “Indeed” for example increased by 5% from the end of July to the end of September.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: