Stage Set for a Swifter Economic Recovery in the Maritime Provinces

Omar Abdelrahman, Economist | 416-734-2873

Date Published: April 19, 2021

- Category:

- Canada

- Provincial and Local Analysis

Highlights

- Although no province has been left unscathed, the economic fallout from the pandemic has been less severe in the Maritime provinces.

- We estimate that the region suffered a comparatively smaller hit to real GDP 2020, underpinned by a milder exposure to the pandemic and shorter-lived restrictions on economic activity. And with recent data indicators turning up, the stage is set for a swifter return to pre-pandemic activity levels relative to the Canadian average this year.

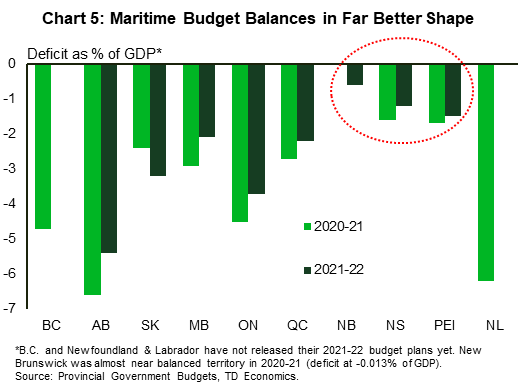

- The Maritime provinces are also on track to exit the pandemic with less fiscal deterioration than most other provinces. This may allow for some added policy flexibility during the recovery phase.

- A potential fly in the ointment for the Maritime provinces is population growth. In the years just prior to the pandemic, the three provinces had been enjoying solid economic growth, led by higher population growth through international immigration. The pandemic has disrupted these flows. Still, medium-term growth prospects are critically tied to the region's success in restoring population gains to the higher pre-pandemic profile.

The economic fallout from the pandemic has taken its toll on every region in Canada – including the Maritime provinces. Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia's important tourism industries have been hard-hit by travel disruptions. Exports in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia tumbled as demand for petroleum and seafood products dwindled. Across the region, the slowdown in international immigration halted progress on the population growth front - a critical component of these provinces' above-trend performance immediately prior to the pandemic. The second wave of infections and restrictions were far milder compared to other regions, but it still triggered short-lived lockdowns and a temporary halt to the "Atlantic Bubble." This further strained the region's service sector in recent months. Uncertainty continues to linger, with the third wave further delaying the reopening of the "Bubble."

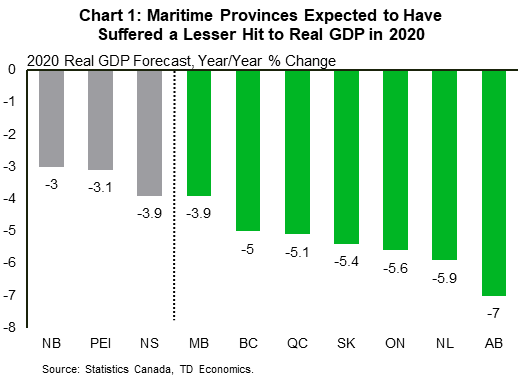

Notwithstanding these setbacks, the Maritime provinces appear to have avoided the worst of the pandemic-induced downturn witnessed in other parts of Canada and, indeed, across many parts of the world. Our latest Provincial Economic Forecast assumed a shallower decline in real GDP for these provinces in 2020 (Chart 1), followed by solid across-the-board rebounds in 2021 and into 2022. The service sector should underpin the recovery going forward. Other forces have joined in to lift near-term projections, including a brightening export backdrop amid massive US stimulus, strong capital spending intentions, and supportive Canadian fiscal policy. Though still early days, a milder third wave and lesser restrictions thus far points to continued outperformance for these provinces in the spring. Medium-term, a potential fly in the ointment for the region is uncertainty around its population growth. A renewed focus on achieving strong immigration flows will be critical to offsetting the region's aging demographics.

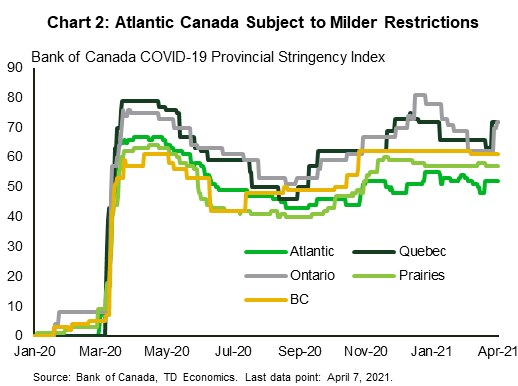

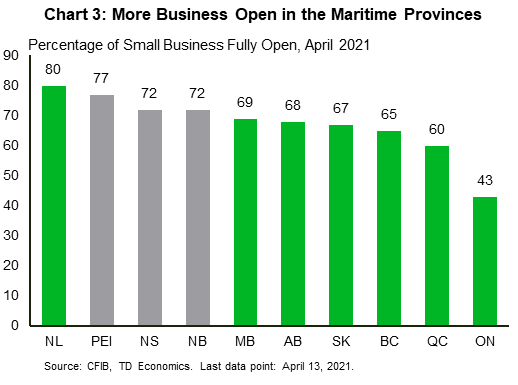

A Relatively Mild Pandemic Exposure and Limited Restrictions

Providing a backstop to the region in 2020 and early 2021 was its relatively mild exposure to the virus. On a per capita basis, the Maritime provinces maintained the lowest caseloads across any jurisdiction in Canada, and more broadly, North America. Throughout the pandemic, restrictions on businesses were typically short-lived and less stringent than seen in other regions (Chart 2). Western Canada's restrictions were similarly less stringent for most of 2020, but a higher caseload and strains elsewhere in the economy, such as in the commodity industries, weighed heavily on activity. No province's economy is out of the woods yet, but the third wave has only resulted in isolated new restrictions thus far (for instance, in the Edmunston region in New Brunswick). In turn, the Maritime region continues to see a greater percentage of businesses open (Chart 3).

Labour Market Outcomes Mixed, but on Track to Outperform

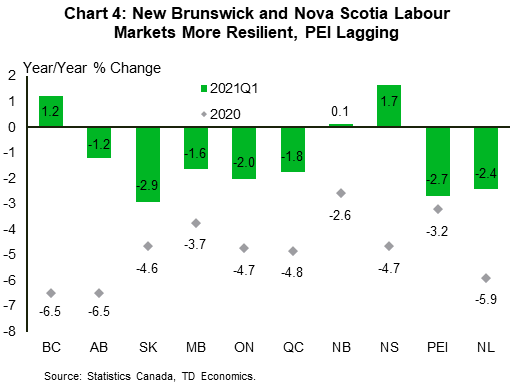

A defining feature of the pandemic-induced downturn was the unprecedented hit to labour markets. All three Maritime provinces were no stranger to this. The annual average decline in employment was the most severe since comparable data collection began in 1976 in both Nova Scotia and PEI. The toll on the region in 2020, however, was still milder than that seen in many other provinces (Chart 4).

A defining feature of the pandemic-induced downturn was the unprecedented hit to labour markets. All three Maritime provinces were no stranger to this. The annual average decline in employment was the most severe since comparable data collection began in 1976 in both Nova Scotia and PEI. The toll on the region in 2020, however, was still milder than that seen in many other provinces (Chart 4).

Labour market outcomes diverged across the region during the recovery stage. Broadly, we expect the region as a whole to recoup most of its job losses by the second quarter, although PEI may lag. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia had broadly outpaced other provinces in the recovery process since the sumer of 2020, with Nova Scotia virtually back to its pre-pandemic levels of employment last March. What's more, the labour force partcipation rate in both provinces has also recovered back to pre-pandemic levels, easing concerns around long-term scarring. This outperformance relative to other provinces narrowed in March as other provinces relaxed restrictions, but is expected to widen again during the spring months. Aided by relatively short-lived restrictions, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick's outperformance was evident in the high-touch services industries. Elsewhere, Nova Scotia's higher concertation of professional and financial services industries was also supportive.

Meanwhile, Prince Edward Island's post-pandemic labour market recovery has been more elongated relative to most other provinces, but this comes on the heels of an unsustainably strong turnaround in the three years prior to 2020. The strong hand-off to 2020 limited the overall annual decline. Prince Edward Island's exposure to the hard-hit tourism industry dampened its labour market recovery prospects. The province should see improved prospects once interprovincial tourism resumes, but a return to pre-pandemic hiring strength is unlikely prior to the resumption of international tourism in 2022.

Consumer Spending Weathering the Storm

Though consumer spending and population growth were still heavily impacted by the pandemic, household outlays staged a strong, V-shaped rebound across the region since last spring, outperforming Canada as a whole. Retail sales have defied gravity, with both New Brunswick and PEI managing to turn in growth for the full year in 2020, while Nova Scotia posted a relatively modest drop. The outperformance relative to most of Canada's larger provinces is largely driven by spending on gasoline and some discretionary items (for instance, motor vehicles and clothing). Elsewhere, the Maritime provinces also saw a lesser (though still drastic) hit to sales at restaurants. This outperformance can once again be explained by low caseloads, greater mobility, and faster reopenings. Together with Newfoundland & Labrador, these provinces also enacted an "Atlantic Bubble". The resulting increase in interprovincial tourism provided a partial backstop to the ailing "high-touch" industries during the key summer months.

As herd immunity is approached, the boost from pent-up demand may not be as strong as that in the rest of the country, given the less drastic dent seen last year. Still, outperformance is expected to remain in the near term, aided by lower restrictions and case counts, as well as a possible resumption of the Atlantic Bubble in May. Like its other provincial peers, wealth effects, underpinned by robust home price growth, should also help to grease the spending wheel. The significant increase in household savings should also be supportive.

Public Finances Resilient

A uniform theme across the Maritime region is the relatively mild hit to public finances. All three provinces saw the lowest deficits (as a percentage of GDP) in the 2020-21 fiscal year (Chart 5). Likewise, the increase in debt burdens paled in comparison to some of Central and Western Canada's provinces. Remarkably, New Brunswick ended the 2020 near balanced territory (a -0.03% of GDP deficit). PEI and Nova Scotia's deficits were also manageable, at 1.7% and 1.6% of GDP, respectively. Against the backdrop of a milder pandemic exposure, these provinces faced a smaller increase in spending needs, and in some cases, a shallower hit to own-source revenues. Federal transfers were also critical in supporting revenues – especially in provinces were transfers constitute a large share of revenues. All three provinces were also in the black prior to the pandemic, having successfully balanced their budgets following the hit from the global financial crisis.

The lesser fiscal hit through the pandemic has provided additional wiggle room for governments in the region to announce some new measures in this year's budget season. For instance, all three provinces revised upwards their capital spending plans, with Nova Scotia's hitting another record year ($1+ billion). On the operating side, PEI was even able to add tax relief measures while maintaining the third lowest deficit as a percentage of GDP. Fiscal positions across the region could outperform forecasts given the cautious nature of economic planning assumptions and the federal commitment to raise health transfer payments subsequent to the release of the provincial budgets. As a result, all three provinces are likely to return to black ink prior to the rest of the country. Debt burdens, while still on the relatively high side, are expected to remain below their record highs. At the same time, relative comparisons to other provinces' debt burdens (for instance, Ontario and Quebec) have improved.

Other Supportive Drivers

A range of factors have joined in to boost prospects in 2021 and 2022. The region should benefit from an increase in exports on the back of sizeable U.S. fiscal stimulus. This is specifically true for New Brunswick, which has the highest export exposure to the U.S among the provinces and is also benefitting from a rebound in demand for petroleum products and solid demand for forestry products. Based on 2021 capital spending intentions data, New Brunswick is also expected to benefit from a surge in both private and public sector capital expenditures. Private capital expenditure intentions in Nova Scotia are also strong, complemented by record infrastructure spending intentions in the 2021 Capital Budget. PEI's private capital expenditures are projected to lag, but its provincial capital budget suggests that public sector spending will provide some offset. Housing markets have also been surging, unabated, for the past two years. Prices have recently been running at a double digit pace, building on trends seen prior to the pandemic. A downshift to more sustainable levels of activity should be expected, in tandem with the rest of the country. Still, a return to strong international immigration, a favourable interprovincial migration picture, and affordability should keep trends on a solid footing, at least in comparison to the post financial crisis time period.

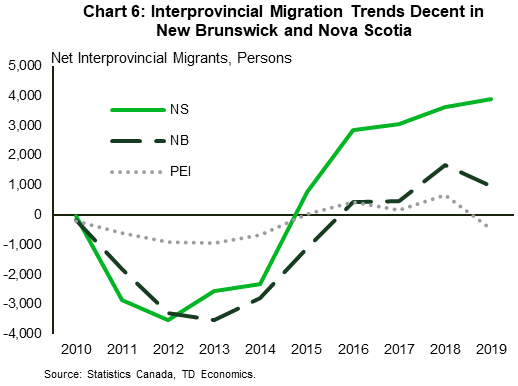

Potential Fly in the Ointment: Immigration Critical to Medium Term Prospects

As the dust settles after COVID-19, population growth will re-emerge as the key theme shaping the region's prospects. A big part of the region's above trend performances in the two years preceding the pandemic is attributable to a surge in population growth. This came after the region's population growth dangerously fell into negative territory at the start of the past decade. Improved economic prospects and weakness in Alberta's economy also left these provinces with favourable interprovincial migration trends in recent years (Chart 6). The return to positive population growth bolstered housing markets and consumer spending. Importantly, it also supported growth in labour force and employment. These flows have temporarily slowed to a crawl as a consequence of COVID-19. Indeed, international immigration has dropped by more than 50%. The federal and Maritime governments have reiterated plans to boost immigration in upcoming years. Without domestic and international migrant inflows, the region's demographic trends would likely revert back to the weakest in the country (together with N&L), with all three provinces suffering from a negative natural rate of increase in population. As a result, following through on these plans to increase the intake of newcomers will be critical to the region's medium- and longer-term prospects.

Bottom Line

While still facing a significant hit from the pandemic, the Maritime provinces have weathered the economic storm better than others. All three provinces appear well-positioned to return back to pre-pandemic levels of activity prior to most other regions. Looking ahead, the medium- and long-term outlook will strongly hinge on the region's ability to attract newcomers and maintain strong population growth.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics arWhile still facing a significant hit from the pandemic, the Maritime provinces have weathered the economic storm better than others. All three provinces appear well-positioned to return back to pre-pandemic levels of activity prior to most other regions. Looking ahead, the medium- and long-term outlook will strongly hinge on the region's ability to attract newcomers and maintain strong population growth.e not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: