Highlights

- Canada’s job market remains a key pillar of strength for an economy facing no shortage of uncertainties in the months ahead.

- Job growth has consistently outperformed, with firms in cyclically sensitive sectors driving the gains. While the overall unemployment rate remains high, it is skewed by younger workers in a few lower wage, lower education sectors.

- The solid starting point of the labour market is crucial as Canada navigates the threat of potential trade tariffs, slowing population growth, and an upcoming federal election.

Canada’s economy is facing no shortage of risks in the months ahead, from the potential of U.S. tariffs to a population slowdown to uncertainty around the upcoming federal election. On the plus side, Canada’s labour market is starting 2025 in solid shape, providing a decent foundation to the economy as it navigates this potentially bumpy period. Indeed, for all of Canada’s economic challenges – weak economic growth, poor productivity, and deteriorating housing affordability – the job market has been serving as a pillar of economic stability.

Pulling Back the Curtain on Canada’s Job Market

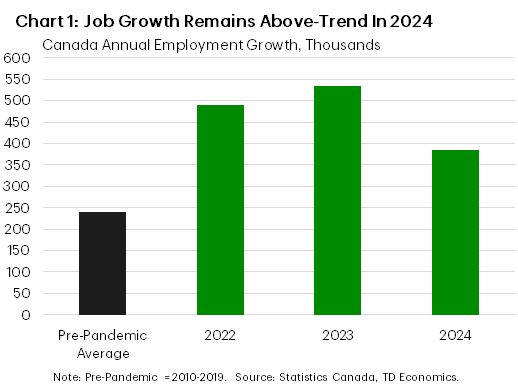

The labour market’s sturdy performance has been particularly showcased in job creation figures. Annual employment growth has consistently outpaced pre-pandemic levels, with the labour market churning out another 385k positions this past year (Chart 1). For 2024, this equates to an average of 32.1k jobs per month, with nearly 80% coming from full-time positions. Solid hiring momentum carried through to the New Year as the economy added 76k jobs in January.

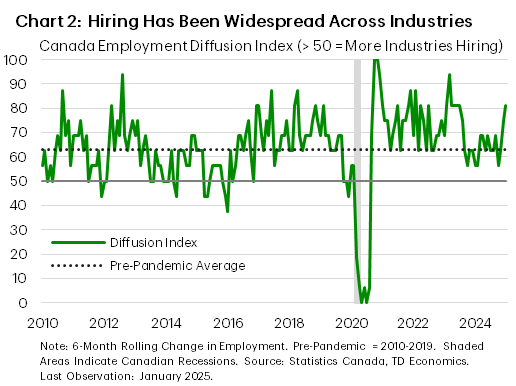

Beyond the sheer number of jobs created, the breadth of hiring has proven strong as well. Canada’s employment diffusion index shows that job growth has been broad-based across sectors, with roughly two-thirds of industries expanding employment each month in 2024 (Chart 2). Notably, over half of new jobs created in the past year were in so-called “cyclically sensitive” sectors such as finance, real estate, construction, and professional, scientific, and technical services, highlighting the labour market’s resilience.

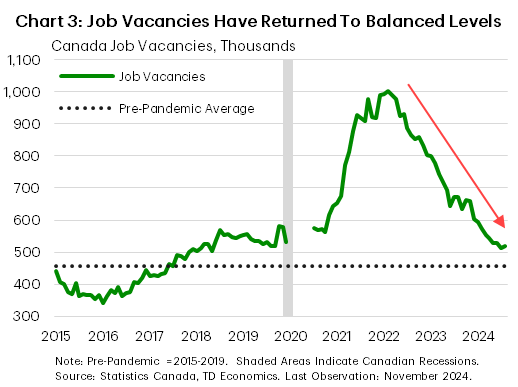

Other indicators also point to balanced labour market conditions. Job vacancies pulled back sharply through much of 2023 and 2024. However, this shift largely reflects a “normalization” following the post-pandemic hiring surge, rather than a sign of broad weakness. More recently, the decline has abated, suggesting that vacancies may have found some support around its pre-pandemic average (Chart 3).

Job vacancies are a primary driver of wage growth, and their stabilization has helped balance wage pressures as well. In January, wage growth eased to 3.5% year-on-year (y/y), down from the 5.0% y/y gains seen for much over the past two years. Meanwhile, hours worked had also slowed over 2024, reaching a low of 1.1% y/y in September. But with the rebound in hiring since the fall, hours worked has now pushed to a very robust 2.2% y/y pace as of January. This should feed through to strong GDP growth, which can, in turn, spur greater hiring.

Unpacking the Unemployment Rate

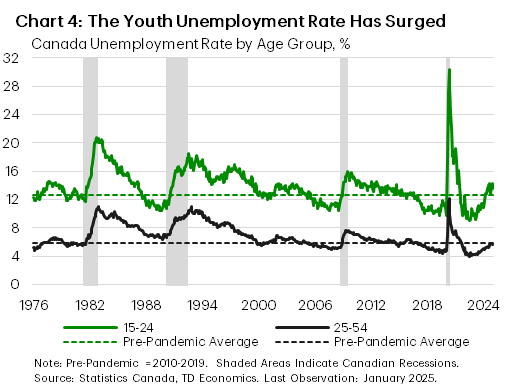

While we argue that Canada’s job market remains on solid footing, critics often cite the elevated unemployment rate as evidence to the contrary. Over the past two and a half years, the jobless rate has climbed a whopping two percentage points (ppts), peaking at 6.9% before pulling back slightly to 6.6% in January. Importantly, there is a large demographic angle to the rise in the unemployment rate. Canadian youth have led the upward move. The unemployment rate for workers aged 15-24 has surged by over 5 ppts, reaching a peak of 14.2% at the end of 2024 – levels typically seen in past recessions (Chart 4). The prime working-age population (25-54 year olds), comparatively, has an unemployment rate of just 5.6%, which is below pre-pandemic levels and a full ppt lower than the headline rate. While Canadian youth are experiencing recessionary levels of unemployment, it is clear that the majority of Canada’s labour force is not.

The rise in youth unemployment coincides with the growth of the non-permanent resident (NPR) population. Indeed, at the end of 2024, there were over 3 million NPRs residing in Canada, more than double the amount from two years ago. And NPRs are generally young, with many falling in the 15-24 age group, as students and younger workers comprise the majority of new arrivals. It is no surprise the newcomer unemployment rate has also reached ultra-elevated levels, peaking at 12.6% in 2024, 5.2 ppts above the post-pandemic low. What’s clear is that newcomers to Canada are struggling to find employment.

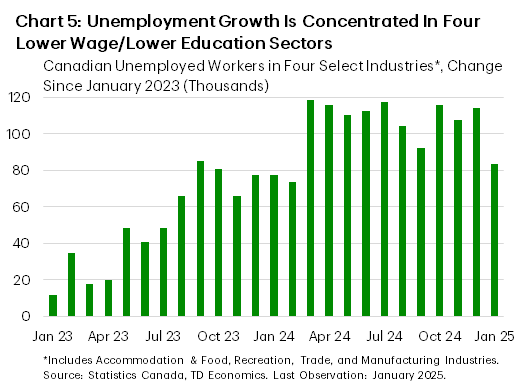

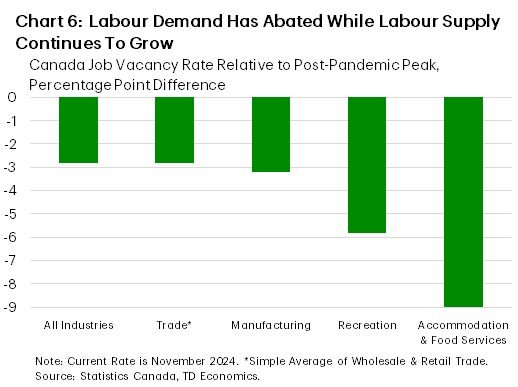

The uneven balance of Canada’s unemployment landscape is also apparent when we look at the demand and supply of workers by industry. Since 2023, about half of the increase in unemployed workers has come from just four lower wage, lower education sectors: Accommodation & food services, recreation, wholesale & retail trade, and manufacturing (Chart 5). When looking at job vacancy data, these industries previously had very high job vacancy rates just a couple years ago (hence the flood of NPRs) but have now pushed towards all-time lows (Chart 6). While labour demand has dropped, labour supply kept increasing, creating a drastic oversupply of workers. Since 2021, the labour force in these four sectors has expanded by an average of 12.3%, compared to just 8.8% in all other industries. This mismatch between labour supply and labour demand has created a perfect storm for a highly skewed rise in the unemployment rate.

Looking Out to an Uncertain Future

When it comes to forecasting in 2025, we are reminded of the Donald Rumsfeld “known knowns” quote discussing risk. Specifically, Canada has many risks that are known (ones it can prepare for), but also many “known unknowns” (ones that are hard to prepare for).

On the domestic risks that we currently know about, changes to the country’s population strategy rank as the biggest. The federal government has backtracked on its previous errors, promising to cut immigration levels and slash the number of NPRs by 1.4 million. Please see our recent report on the details. The imbalances in the supply of labour in low wage/low education sectors will start to unwind, with less unemployed workers available. This will likely put downward pressure on the unemployment rate, which we think could shrink to a more comfortable 6.0% by 2026.

Importantly, we don’t anticipate a major hit to aggregate spending due to weaker immigration inflows, as the impacts are likely to be more than counterbalanced by rising outlays per household. This improvement should be reflected in Canada’s GDP per capita, which has been negative for seven of the last eight quarters but is now expected to return to growth in early 2025.

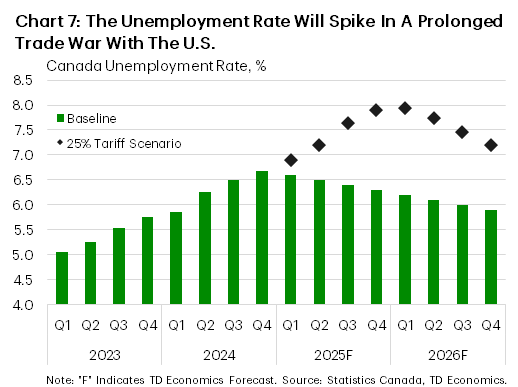

The existence of a combative U.S. administration requires us to add a caveat to this view. The known unknown of Donald Trump speaks to the political uncertainty that the president creates. Even if the administration backs off from its severe tariff threats, ongoing uncertainty will weigh on business investment and hiring. While our baseline still points to another respectable year for overall job growth, a flare-up in tit-for-tat tariffs between Canada and the U.S. would push the Canadian economy into a recession. Under that downside scenario, the unemployment rate would spike by around 2%, as firms shed labour, even as the supply of workers is shrinking (Chart 7).

Bottom Line

2025 was supposed to be a year of improved economic growth, as lower rates would bring renewed life to Canadian consumers and businesses. We have already seen nascent signs of this developing, with retail trade data and housing activity showing improved consumer optimism. This steady growth trajectory, along with easing population flows, would act to push the unemployment rate back to normal levels by year-end, bolstering the solid state of the labour market.

The overhang of President Trump’s trade policies and America first attitude risks what otherwise should be a solid year for the Canadian economy. Much will depend on the depth, breadth, and duration of U.S./Canada trade tensions. A worst case scenario of steep across-the-board tariffs on Canadian imports and forceful retaliation by Canada would surely be a bitter blow for the job market, but should a deal be struck in short order, it is reasonable for us to assume that the previously optimistic rebound for the Canadian economy, supported by solid labour market fundamentals, could prevail.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: