Canada’s Food Price Misery Has Company South of the Border

Leslie Preston, Managing Director & Senior Economist | 416-983-7053

Date Published: January 27, 2026

- Category:

- Canada

- Latest Research

- Consumer

Highlights

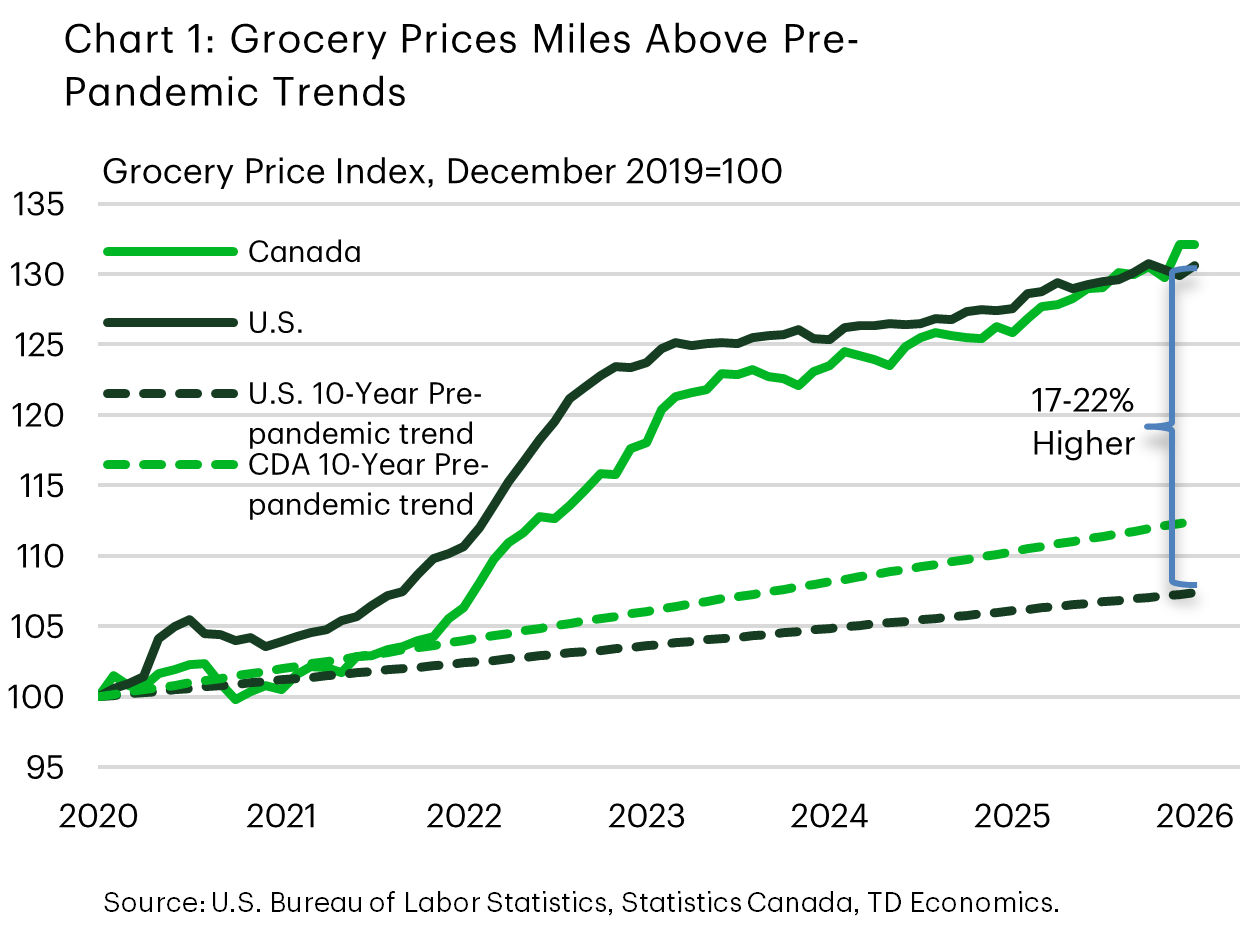

- There’s merit to why Canadian sentiment reflects the sting of food inflation, with grocery prices up over 30% since 2019, even as overall inflation seems to settle. Even the Federal Government has taken notice, making the GST credit more generous among other measures to help make food more affordable.

- Canada’s food prices have moved similarly to those in the U.S., driven by global factors, but more recently Canadian food inflation has been higher. This may in part be due to counter-tariffs on U.S. imports and earlier weakness in the Loonie.

- Groceries make up a larger share of Canadians’ budgets than Americans’, so higher prices hit harder. Relief on food inflation is expected in the coming months, but without a fall in the price level, Canadian perceptions will be slow to change.

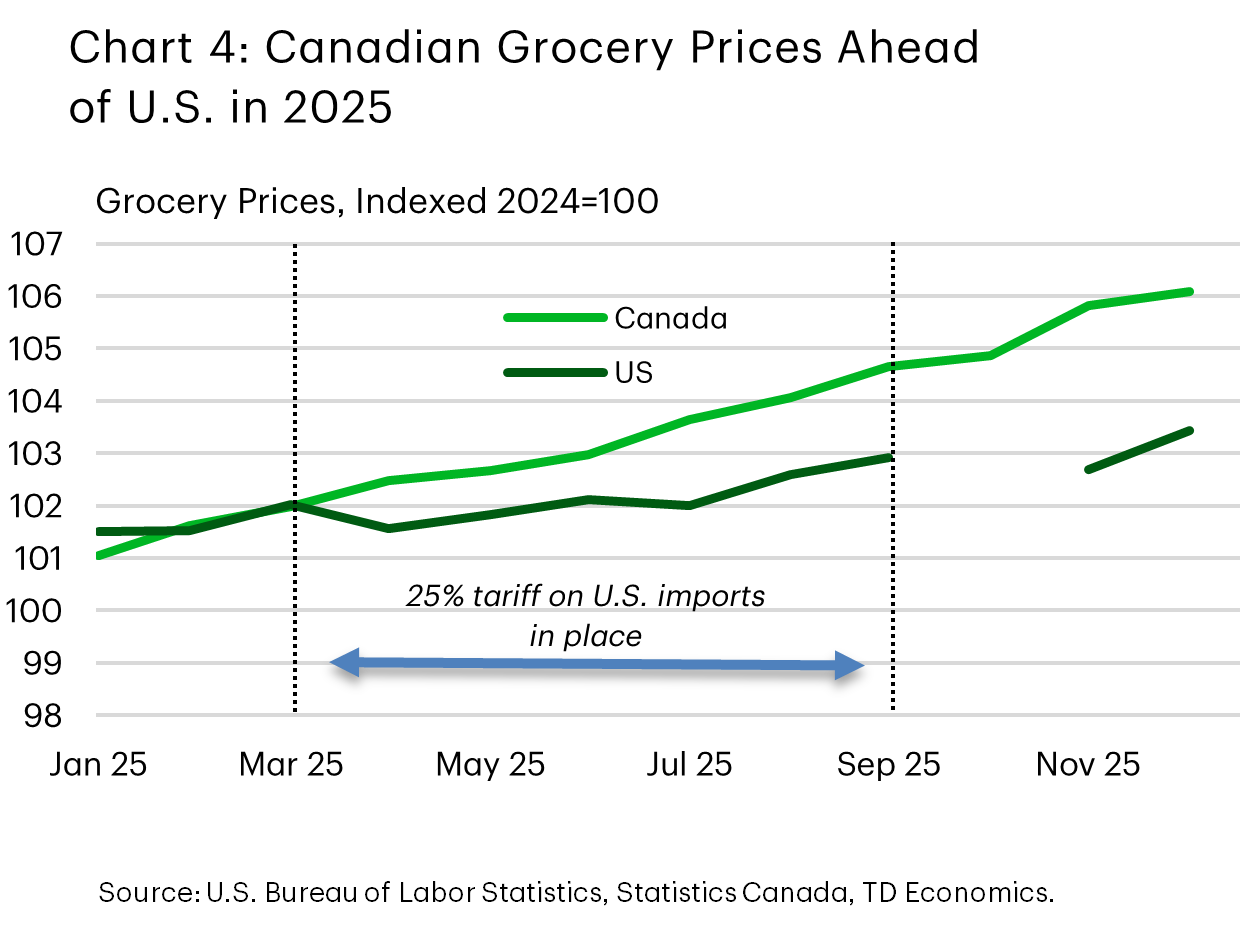

The Federal Government has taken notice of higher grocery prices, rebranding the GST credit the “Canada Groceries and Essentials Benefit”, increasing it 25% starting in July and providing a one-time payment this year. Grocery prices have heated up in 2025, rising twice as fast as headline inflation in recent months. It was appropriate the government take action given it was the government’s 25% retaliatory tariffs on U.S. imports that were at least in part responsible for higher food prices over the past several months. Despite counter-tariffs being lifted in September, price increases for food show few signs of abating. Consumers continue to report feeling the squeeze of higher prices—especially at the grocery store. According to the Bank of Canada’s Consumer Expectations survey, consumers perceived inflation to be at around 4% in the fourth quarter of 2025, when actual inflation was reported at 2.3%. It is often the case that consumers perceive inflation to be higher than it is, but the gap has become wider since the pandemic. However, maybe consumer perceptions are not that far off from reality. Groceries have one of the most visible and immediate impacts on household wallets, and inflation for these items was 4.4% in the fourth quarter. The essential and frequent purchase of food likely factors more heavily into people’s sentiment of inflation.

Food1 prices have become a pain point for consumers since the pandemic. Grocery prices in Canada are over 30% higher than in 2019. Had the pre-pandemic trend continued, that upward pace would have been much slower at only 17% growth (Chart 1). For perspective, the average Canadian is spending over $1600 more per for groceries post pandemic.

Grocery prices climbed faster than any other major category, although shelter inflation wasn’t too far behind. Several forces were at play, including higher energy prices, harsh weather, particularly droughts, labour costs, the value of the Canadian dollar and tariffs (see details from the Bank of Canada here).

The Canadian experience was not an anomaly. Americans also experienced sharp increases in food prices during the pandemic, and these hikes occurred slightly earlier than in Canada. Since 2019, Canadian food prices have climbed only slightly higher than those in the U.S., and only surpassed them in the past year (Chart 1).

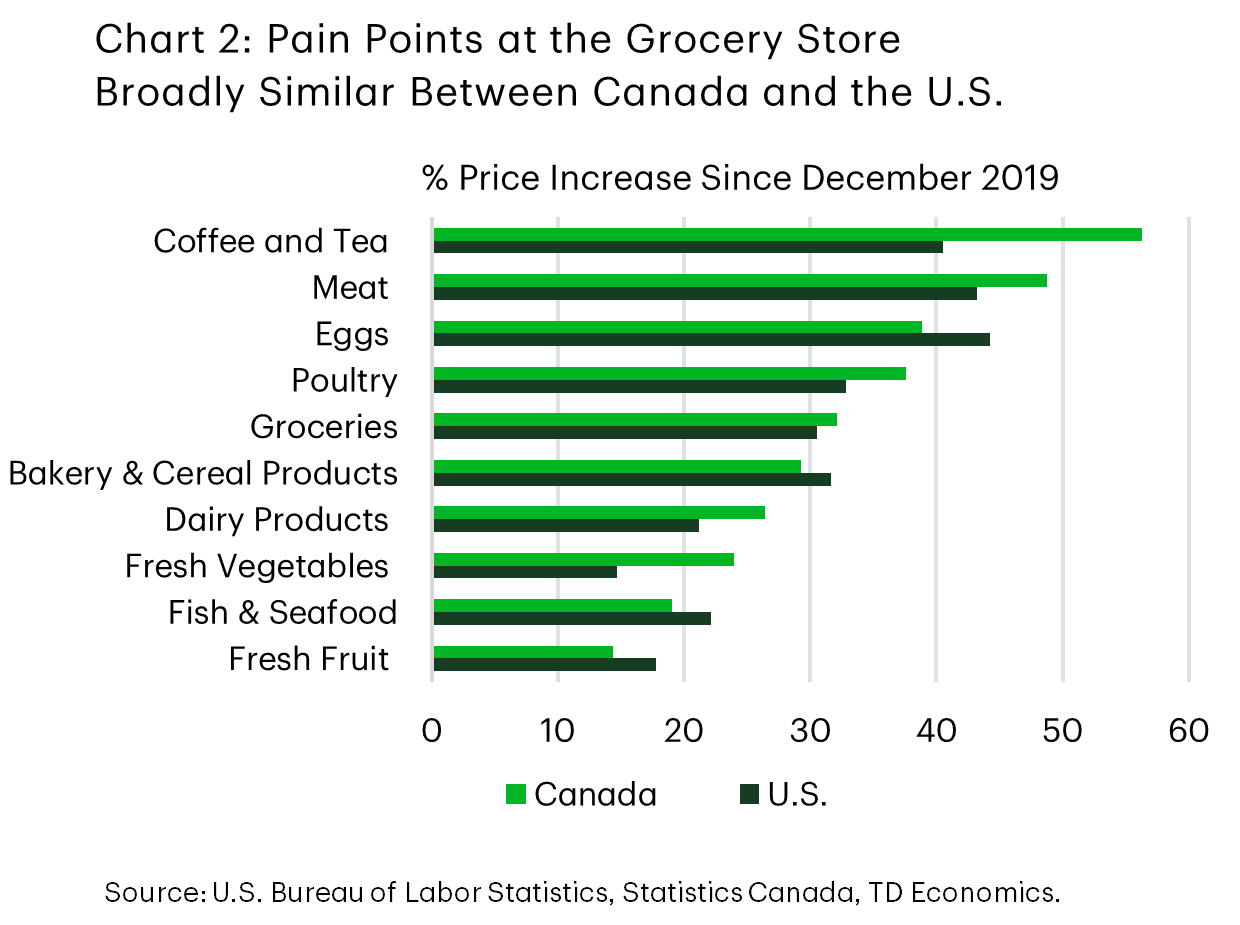

Examining specific food categories where Canadian and U.S. data are comparable, the largest price jumps have been in meat, coffee and tea, with eggs and poultry also seeing above-average increases (Chart 2). These trends mirror those in the U.S., although Americans have faced steeper price increases for eggs—largely because Canada was less affected by the avian flu that disrupted egg supplies south of the border2. On the other hand, Canadians have seen larger price hikes for coffee.

Overall, Canadian food prices tend to be less volatile than those in the U.S., as measured by the standard deviation of grocery inflation. This is especially true for categories managed under Canada’s supply management system, such as dairy, chicken, turkey, and eggs, as well as fish and seafood. However, Canada experiences more volatility in coffee, tea, and fresh fruits and vegetables inflation. This is largely because most of these items are imported—especially during the winter—making their prices sensitive to fluctuations in the Canadian dollar. By contrast, the U.S. produces more of its own fruits and vegetables, tempering price volatility in these categories. While food prices are less volatile in Canada due to supply management, our higher share of imported food makes our prices more dependent on currency fluctuations.

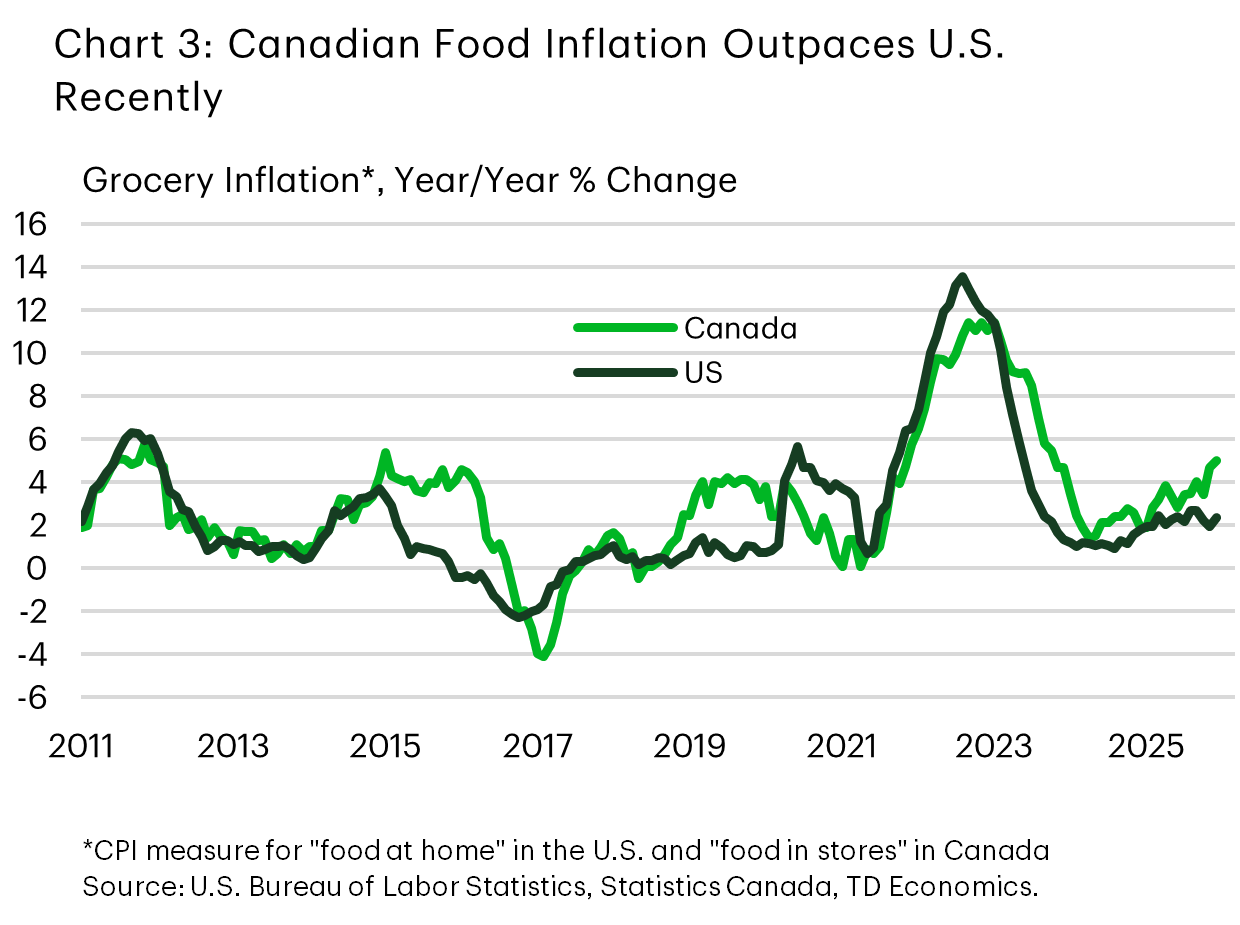

Over the past year, Canada’s food inflation has run ahead of the U.S. (Chart 3). Other factors have been at work, namely the 25% retaliatory tariffs on U.S. imports that were in place from March to August. This would have been compounded by a generally weaker Canadian dollar in 2025. The U.S. had supplied roughly half of our fresh fruits and vegetable imports, and more than half of our processed foods imports, so a 25% import tariff on these goods would certainly have led to price increases in store shelves (Chart 4). With tariffs lifted in September, it is taking some time for that relief to show up, but should be on the way in the coming months.

Even so, it’ll be hard for policymakers to change perceptions of food inflation within short order. First, even though food inflation in Canada has alignment to trends south of the border over the past several years, grocery bills make up a larger share of Canadian household budgets. Groceries represent 11% of the CPI basket in Canada, compared to 8% in the U.S. This means the impact of higher grocery prices is felt more acutely by Canadian families. The impact is even larger for lower-income households. The lowest 20% of households by income spend 14% of their budgets on food, in contrast to the 10% spent by the top 20%.

Second, the level of prices is unlikely to reverse course. Meaning, that $15 per kilo for ground beef, is unlikely to suddenly drop to $10 per kilo, where it sat three years ago. Inflation is a measure of growth, not levels, and most consumers are not calculating the year-on-year increase as they shop, they remember the price. And while economists and policymakers can point out a flattening in inflation as a positive outcome, that won’t undo the recency bias of where people remember prices to have been not too long ago. It will take time for the shock of recent price increases to wear off, and for the higher price level to seem normal.

End Notes

- When this report refers to food, the specific measure is food purchased from stores in Canada or food at home in the U.S., not the broader food category that includes food at restaurants.

- In Canada, barns are more tightly sealed due to weather, which keeps infected wild birds out, and farms are smaller (due to supply management) so an outbreak at one farm is less far reaching.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: