Dollars and Sense

What’s Holding Up Longer Term Yields?

Date Published: August 12, 2025

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Highlights

- It’s not a household term, but the term premia embedded in bond yields sure does matter to households. It’s the extra compensation investors demand for holding long-term debt, which in turn pushes up borrowing rates.

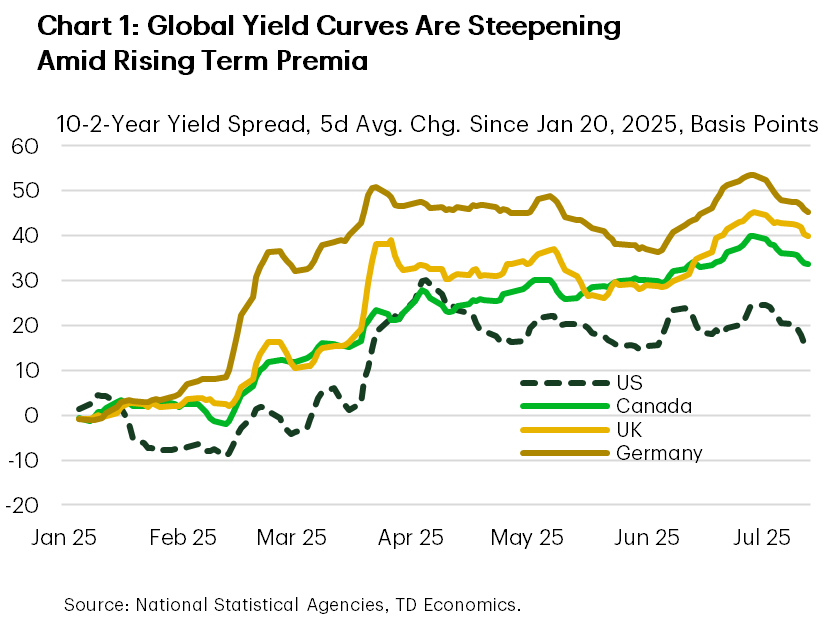

- Globally, yields are being held up by an extra 30 basis points since January 2025.

- The U.S. has managed to avoid a steep increase in the term premium through a combination of a favourable market narrative and issuance strategy.

- But uncertainty around growth, fiscal sustainability, geopolitical volatility as well as structural factors will continue to fight against lower term premia. And the risk of another leg higher cannot be dismissed.

August 1 brought a sharp repricing in U.S. yields. A disappointing jobs report, coupled with a weak ISM manufacturing survey, sent the two-year Treasury yield plunging by 25 basis points – one of the largest one-day declines. The reaction further out the curve was more guarded. The 10-year yield fell by 14 basis points, while the 30-year moved down just eight basis points. This steepening of the curve reflects a growing term premium – the extra compensation investors demand for holding long-term debt versus rolling over short-term bills.

Global Repricing of Long-Term Risk

This repricing isn’t isolated to the United States. Global term premia started rising several weeks after the Trump administration revealed a more fundamental shift in trade policy than markets anticipated – one marked by bilateral deals, a retreat from multilateral agreements, and punitive tariffs to reshape global production. Markets are now adjusting to the implications of a more fractured global trade regime, and the uncertainty that comes with it.

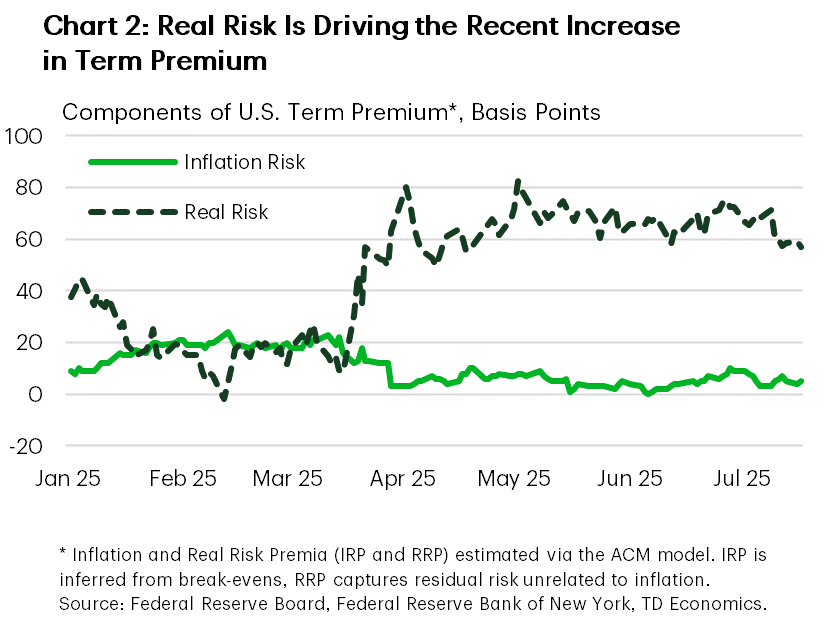

Since then, term premia have risen across major developed markets. Measured by the yield spread between 10-year and 2-year government bonds, global curves have steepened by an average of 30 basis points (Chart 1). It does not appear the widening has been driven by higher inflation expectations, despite trade friction that results in less efficient supply chains. One practical way to estimate the inflation component of the term premium is to compare break-evens (the spread between nominal Treasuries and TIPS) with five-year forward inflation rate. That spread has moved only modestly, and forward inflation measures remain relatively anchored.

Instead, the bulk of the increase reflects a rise in the real risk premium. This is a residual component of term premium that captures uncertainty around growth, fiscal sustainability, and geopolitical volatility, as well as evolving supply-demand dynamics for long-term bonds (Chart 2).

Who’s to blame?

The initial rise in term premium wasn’t led by the U.S. – it began in Europe. German 10-year bund yields rose sharply from 2.4% in February to nearly 2.9% by mid-March. That move coincided with Germany’s announcement of a €900 billion multi-year fiscal program focused on defense and infrastructure. This is a new fiscal element in the euro area, the U.K., and Canada, where governments are laying the groundwork for large defense-related outlays. According to the IMF’s April projections, the euro-area’s fiscal deficit is set to widen from 3.1% of GDP in 2024 to 3.5% by 2027. However, since then, the fiscal outlook has been further challenged. The June NATO summit formalized commitments with member countries pledging to raise defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035. In most cases, this new spending will be financed through bond issuance, pushing up long-end yields and term premia across sovereign curves.

On this side of the Atlantic, the U.S. term premium has risen more modestly than in its peer economies. The 10-2 yield spread has risen by less than 20 basis points. This is surprising given that the U.S. faces a large and growing fiscal deficit, driven by new spending priorities and structural mismatches between revenues and expenditures. Even with projected tariff revenues expected to lend an offsetting hand, the U.S. fiscal gap will remain wide and will need to be financed through borrowing. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the U.S. deficit is projected to settle at around 7% of GDP by 2027 – up from 6.4% in 2024. The CBO’s projections don’t include tariff revenues. In the unlikely event that the U.S. continued to import from various countries as it has in the past, tariff income would total around $525 billion per year. This would partially offset new spending and reduce the projected deficit to roughly 5.3% of GDP by 2027, albeit this is still high by historical standards absent a downturn. By all accounts, this should be raising concerns about debt sustainability. And yet, estimates of U.S. term premium remain well below the levels observed in the euro area, the U.K. and Canada.

Several factors may explain this. First, markets may be partially buying into the U.S. administration’s view that tariffs will generate revenue, narrow the trade deficit, attract foreign capital, and spur domestic investment – all while keeping inflation in check. If this view holds, the U.S. growth outlook may be stronger than peers. Second, despite recent retrenchment in U.S. dollar and dollar-denominated assets, global investors still view the U.S. Treasury market as uniquely deep and liquid. In a world of elevated uncertainty, that status confers a safe haven premium, effectively suppressing the term premium relative to other sovereigns.

Stealth QE

Another key factor that might be keeping the U.S. term premium in check is the Treasury’s issuance strategy. In the most recent quarterly refunding announcement, the Treasury committed to holding issuance of longer-dated securities steady, while modestly increasing issuance at the front end. At the same time, it expanded its buyback program aimed at retiring older, less liquid long bonds from circulation. The net effect of this strategy is a shrinking pool of long-dated bonds. By keeping issuance constant and accelerating buybacks, the Treasury is effectively tightening the supply of duration in the market, which helps cap long-term yields.

Treasury Secretary Bessent has acknowledged that shifting borrowing toward more traditional long-term issuance could put upward pressure on yields, noting that the long end “will need to be deftly handled.” Still, he opted to preserve the same strategy used by his predecessor – one he had previously criticized and which some refer to as “stealth quantitative easing.” This can not be sustained indefinitely. A growing deficit requires more borrowing, and eventually the Treasury will need to shift issuance toward longer-term debt to prevent the share of T-bills from deviating too far above the optimal range of 15-20% in order to limit rollover risk. The timing of that shift will be critical. If it coincides with rising investor concern about fiscal sustainability or inflation, it could trigger a sharp upward repricing in term premium.

Structural forces

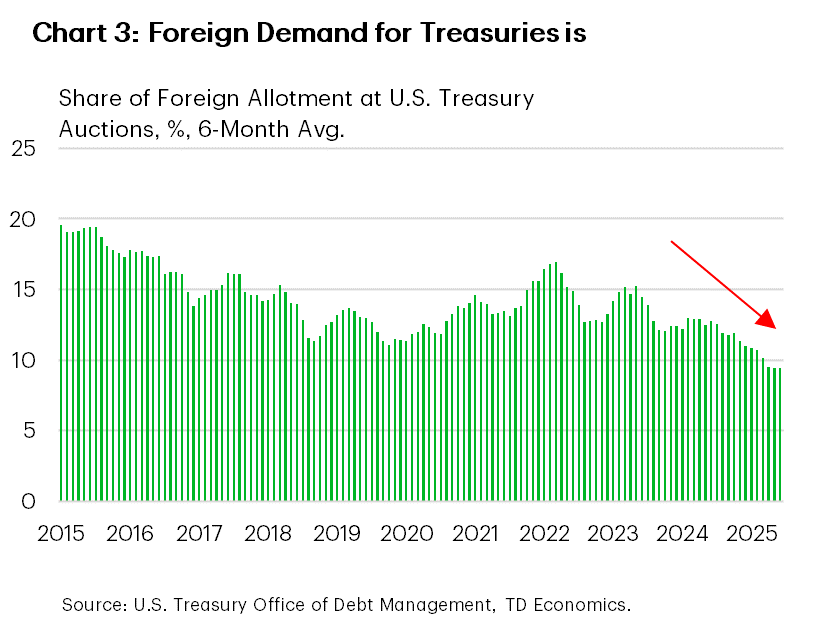

Beyond this, structural factors are also fighting against a lower term premium. Demographics are one reason: as baby boomers retire, their savings rates fall, reducing the domestic supply of capital. Weakening foreign demand for U.S. debt is another. The foreign share of U.S. Treasury holdings declined to 32% in May 2025, down from 48% a decade ago. Meanwhile, the foreign allotment at Treasury auctions – a measure of recent demand dynamics – declined from 21% to 9.5% over the same period, with 2.6 percentage points of that drop occurring in the first half of 2025 (Chart 3).

At the same time, central banks more broadly are retreating from bond markets. According to the OECD, their holdings of domestic sovereign bonds have dropped from a peak of $15 trillion in 2021 to $12 trillion in 2024 and are expected to decline by another $1 trillion this year. This has left more debt in the hands of private investors, many of whom are more price-sensitive and less willing to absorb long-dated risk at current yields. Appetite for duration is waning at the very time supply is rising.

Cuts May Steepen the Curve Further

Until recently, the Fed had maintained a cautious tone, warning that inflation risks remained elevated and that the labor market was still tight. That narrative changed with the August jobs report. Markets are now pricing in a 90% probability of a rate cut in September, up from near even odds prior to the data release.

But even as short-term rates fall, long-end yields may not. Our base-case forecast is for the U.S. 10-2 year spread to steepen from today’s 50 basis points to around 75 basis points by Q2 2026 – close to its historical average. If the real risk premium remains elevated due to fiscal concerns, geopolitical uncertainty, or shifts in demand for long bonds, the curve may steepen further. Moreover, inflation risks haven’t disappeared. The trade war remains a source of potential volatility that can complicate both Fed signalling and Treasury financing options.

Bottom Line

Term premia are rising globally, not because inflation expectations are unanchored but because real risks are growing. From ballooning fiscal deficits to structural shifts in bond demand, long-term risks are being repriced. So far, the U.S. has managed to avoid higher term premium through a combination of a favourable market narrative and issuance strategy. But the risk of another upward leg remains, especially if the Treasury is forced to increase long-dated issuance into a market with fading confidence.

Forecast Tables |

|---|

| Interest Rate Outlook |

| Foreign Exchange Outlook |

| Commodity Price Outlook |

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.