They Get Low and They Get High: Crude Oil Prices Stayin' Alive

Derek Burleton, Deputy Chief Economist | 416-982-2514

Jenny Duan, Economist

Date Published: July 14, 2022

- Category:

- Canada

- Commodities & Industry

Highlights

- Up until recently, crude oil prices had out performed other key commodities but have more recently been tripped up by mounting recession fears and reduced fear about growing global supply shortages.

- Continued supply-demand tightness in the global oil market should limit the scope for further downward adjustment to prices in the coming months. While weakening global growth is likely to see crude consumption fall short of expectations, an offsetting downside risk also looks set to materialize on the supply side.

- We see a greater downside risk to WTI prices in 2023. In the event that advanced economies encounter a mild recession, prices could fall back to US$70-75 or even lower.

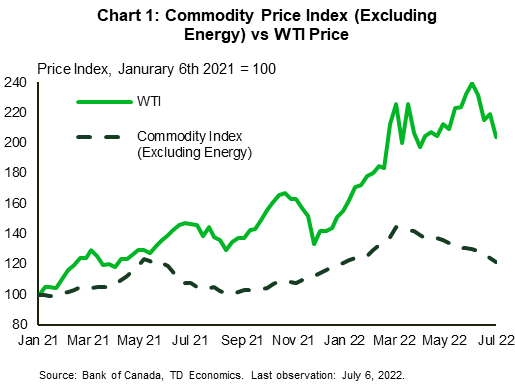

Up to the early summer, crude prices had managed to hold up relatively well compared to a number of other commodities such as copper and lumber. However, that narrative has shifted more recently, with WTI prices falling victim to almost 15% plunge since its peak of more than $120 per barrel in June. Last week, the price slipped below the psychological US$100 per barrel mark, which is a 3-month low. Mounting recession fears, risk aversion and a soaring US dollar that had been dealing a significant blow to the commodity complex more generally have spilled over into the market for crude. (Chart 1).

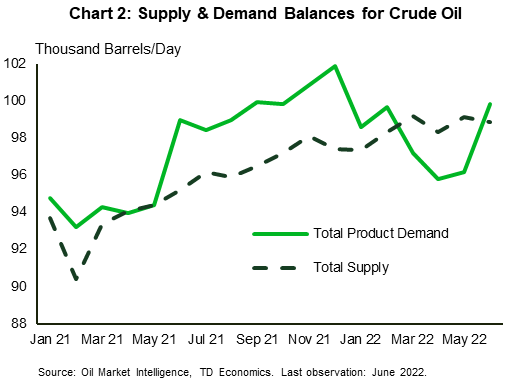

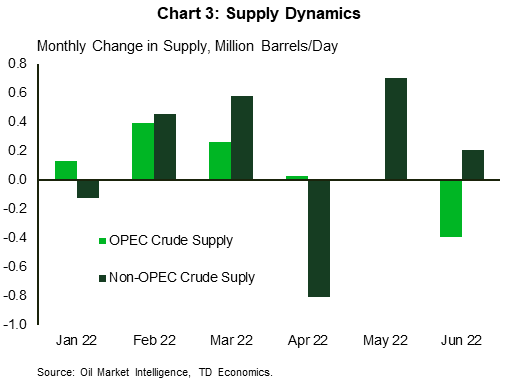

Despite the drop in prices, physical oil markets remain tight, which suggests that the decline in prices seen in recent weeks can largely be chalked up to a reversal in the fear premium that had been steadily building up earlier this year. On a daily production-demand basis, the global oil market stood roughly in balanced territory as of June 2022 (Chart 2) thanks in large part to growing output in non-OPEC countries. These gains have offset the struggles of OPEC to boost its output. Indeed, despite steady modest increases to its overall quota, OPEC supply growth stalled out in April and May before sharply contracting in June (Chart 3).

Chart 2 shows the total demand and total supply of crude oil in 1,000 b/d starting from January 2021 until June 2022. Total crude oil demand surpassed total crude oil supply from May 2021 until February 2022. From February 2022 until May 2022, total supply has surpassed total demand. Chart 3 shows the million barrels per day change in crude oil supply for both OPEC and Non-OPEC countries from January 2022 to June 2022. OPEC crude oil supply is shown to be slowing and even shows a decrease in supply in June. Non-OPEC crude supply fell sharply in April but is starting to increase production in May and June.

OPEC’s challenges in meeting its targets reflect ongoing capacity issues among its members. According to the EIA, the cartel’s surplus capacity (how much more production can be brought online within a month) has dwindled notably to 3 million b/d as of May, down from over 5.4 million b/d in 2021. The decrease primarily comes from the UAE where surplus capacity has fallen from 4.77 million b/d to a projected 2.77 million b/d in 2022.

Further oil price downside appears limited

While prices could head even lower in the coming weeks on a further flareup in global recession concerns, we suspect that much of the bad news is already priced into the market. Key support over the near term will continue to be provided by a fundamental backdrop that shows some signs of bending but not breaking. Accordingly, prices could bobble within a wide range, but are expected to average more than US$100 per barrel through the third quarter.

Consumption appears likely to underperform the latest expectations, notably those imbedded in the June short-term energy outlooks of both the EIA and IEA. Since June, economic forecasts for the U.S. and other industrialized economies have been further ratcheted down. For example, the EIA had assumed global oil demand would come in roughly 1% y/y on average in the second half of this year. These gains would now appear toppish, especially given demand destruction from the past price spike. A profile whereby consumption effectively flatlines looks more likely over the remainder of this year.

Yet, supply too is also showing significant downside risk relative to previous expectations. In its forecast, the EIA anticipated y/y output growth to hold in the 3.5%-4.5% range through year-end. Yet, headwinds on that side are also mounting.

- The EIA further assumes increase supply from OPEC+ in July through to August, but this seems optimistic given current disagreements between Russia, Saudi Arabia and the UAE on revising production quotas.

- The EIA assumes that Russia will ultimately slash oil production by about 2m b/d by the end of the year. However, there appears to be some downside risk to this estimate in light of the introduction of the EU and UK shipping bans, which are not included in the EIA’s baseline outlook. Despite sanctions that have been imposed on Russia, it has managed to sell its oil to Chinese and Indian customers at a discount, with China importing about 2 million bpd in both May and June. However, the sustainability of this demand remains in question especially given the country’s ongoing battle with Covid.

- In addition to the output challenges of OPEC+, non-OPEC members have limited scope to ramp up production significantly higher from current levels due in part to tightening financial conditions and production disruptions in Norway. Within OPEC countries, crude oil theft is hindering Nigeria from meeting its production quotas, while Libya’s political unrest has made production unsteady, shifting between 100,000 b/d to 800,000 b/d.

Greater downside risk to prices is in 2023

The greater potential for an oil price undershoot is not so much over the next few months, but in 2023. For example, the EIA’s price forecast of nearly $100 next year imbeds the assumption that global growth would run at a healthy 3.4% next year. That is 0.7 ppts stronger than our June baseline view of 2.7%, which now could be on the high side given growing storm clouds around the U.S. consumer as well as the overall Euro Area economy. Indeed, in a report we released last week we provided our two cents on how a U.S. recession might unfold if we’re wrong and downside risks to our baseline materialize. We would expect a peak-to-trough GDP decline of roughly 1.7% and a 1.5 ppt jump in the unemployment rate, which would qualify as a relatively mild downturn. This scenario would be consistent with a global growth forecast closer to 2%, which is close to stall speed for a world that typically grows in the 3-4% range.

This alternative scenario would imply a much weaker demand profile. Even under a conservative assumption where global oil demand only increases by half the amount assumed by the EIA in 2023, that would suggest a cumulative build in global inventories of over 600M barrels next year, which would bring the stock of inventory back to a level not seen since November 2020 when oil was around US$40 per barrel.

There will likely remain offsetting upside forces on prices given ongoing geopolitical risks. But even factoring those in, this alternative recessionary outcome would be consistent with prices no higher than US$70-$75. That oil price profile – alongside a prompt softening in labor market conditions globally – would likely drive a hastier retreat back to a lower inflation environment.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: