Recent U.S. economic data are serially exceeding expectations. From the ISM manufacturing and service data that reveal not just resilience but power, to households that reflect a strong appetite to spend their government stimulus checks, to employment gains that signal more of the same is to come in the months ahead. The determination of the U.S. economic rebound cannot be denied – a sentiment echoed by Federal Reserve Chair, Jay Powell, when he stated that the economy is “at an inflection point.” With fiscal stimulus in place and vaccine supply to soon outstrip demand, the U.S. economy is rapidly absorbing any remaining slack. In the months ahead, evidence will mount to support the reflation narrative, prompting Fed members to adjust their forward guidance to signal an earlier rate hike cycle and an end to Quantitative Easing (QE).

Rate Hikes: The Horizon is Coming Into Focus

In the Federal Reserve’s recent Summary of Economic Projections, members dramatically upgraded their employment and inflation outlook. The median voter now sees the unemployment rate dropping below the estimate of full employment in 2022. Core PCE inflation is also expected to accelerate above 2% this year and remain at or above that level for the next few years. Effectively, the Fed will have met its broad policy mandate at least a year earlier than it previously predicted. This should align to a pull-forward in FOMC expectations for rate hikes.

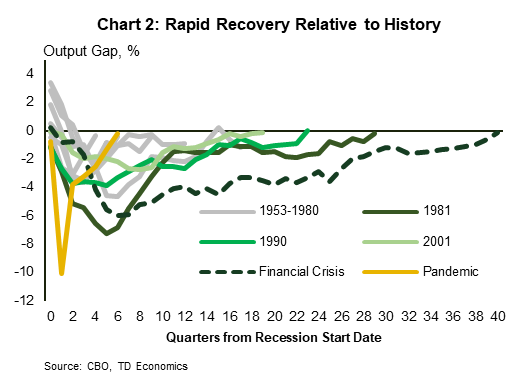

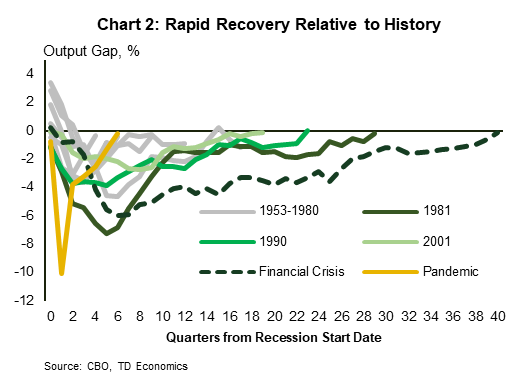

Although the median voter still shows no hikes through 2023 (Chart 1), the individual voting card reveals a growing number expecting earlier rate hikes. Seven FOMC members expect rate hikes in 2023 and four are now expecting the first hike to occur in 2022. Previously only one member stood in the 2022 camp. With respect to how high rates can get, Fed members have been steadfast in believing that the policy rate will eventually end up between 2% and 3%.

Market participants aren’t quite buying what the Federal Reserve is selling and are preparing for an earlier exit from the zero-policy stance. As of writing, the first step forward is priced to start in early-2023, with the policy rate eventually peaking at 1.4% ten years from now. In other words, market pricing is more optimistic than the Fed on the start of rate hikes, but less optimistic with respect to the endpoint.

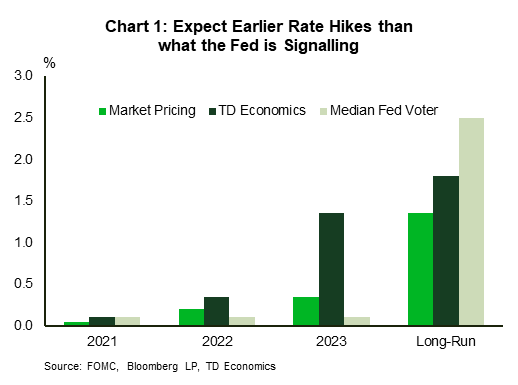

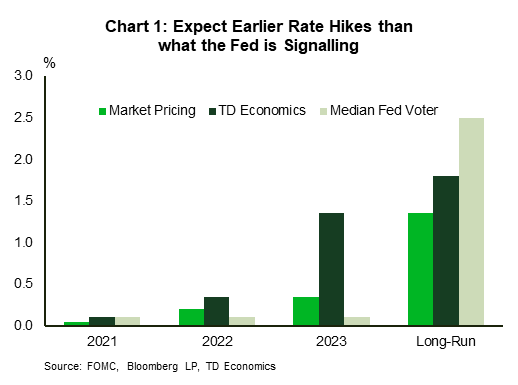

We share the view of the market rather than the Federal Reserve, with the exception that the policy rate endpoint should be roughly 1.85%, or 45 basis points higher than current market pricing. Our near-term view is grounded in a forecast that fully absorbs economic slack by the end of this year, with a recovery shaping up to be one of the quickest in modern history (Chart 2). This is occurring thanks to rising house prices, booming financial market assets, and a strong government safety net. By extension, we expect maximum employment to be reached by the middle of next year and core PCE inflation to move above 2% this quarter and stay there for the next few years. Given its mandate of full employment and average inflation of 2%, the Fed would have a hard time standing still on a zero-bound policy rate by the end of 2022, assuming a one year overshoot of inflation offers sufficient convincing evidence.

Pressure Testing the Forecast

Between the inflation and employment mandates of the Federal Reserve, we have greater confidence in our inflation outlook. That’s because the Fed has indicated repeatedly that it is attempting to pursue a policy approach that is in greater alignment to inclusive employment outcomes. This presents three risks to the forecast. The first is that there can be broad interpretation of where this threshold of inclusion rests or meets a sufficient condition to trigger a rate hike cycle. The second is that the absorption of workers can occur more slowly than anticipated because businesses prove cautious in rehiring or have learned to adapt with fewer workers. The third, and a highly probable outcome, is that re-hiring occurs in sectors that differ relative to where workers were displaced by the pandemic. This could leave the post-pandemic labor market with a greater number of discouraged or structurally unemployed workers.

Even in this world, it’s hard to see the Fed holding the policy rate at the zero bound. We have long been told by central bankers that the policy rate is a blunt tool. It works in the aggregate, but not with surgical precision. Once there’s significant progress and critical mass on healing the labor market, the keys should be turned over to government levels to address specific shortcomings through financial aid, training and employment services. For instance, sustaining a zero-policy rate would do little to influence the outcome for a 55-year-old worker who was displaced from the tourism industry. The risk management lens would need to become focused in the other direction. Leaving rates too low for too long fuels excess behavior in other segments of the market (like asset prices) that can put the entire financial and labor market stability at risk. We are already seeing some of this risky behavior becoming rooted in the stock market, and the housing market is the next most highly exposed. So, resetting Wall Street and Main Street expectations created by easy money will eventually take on greater importance, as economic slack dwindles from both the economy and the job market, even if the latter is imperfect.

Addressing the Balance Sheet

If our economic forecast is correct, the Federal Reserve will have to reconsider its balance sheet policy in short order. Recall that at the onset of the pandemic, the Fed dusted off and expanded upon its policy playbook from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). It re-started liquidity programs to ease short-term borrowing constraints and re-launched its QE program to put downward pressure on yields. It also broadened the types of assets it purchased to include risky corporate debt. Furthermore, it cemented itself as the lender of last resort through its Main Street Lending and Paycheck Protection Program. Put another way, it opened up and deployed the war chest.

Despite a robust recovery forming, the Fed is still actively purchasing government bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) at a clip of $80 billion and $40 billion a month, respectively. At its March meeting, the Fed was steadfast in noting that it will continue QE until there is “substantial further progress has been made toward the Committee’s maximum employment and price stability goals”. Given our view that the U.S. economy should return to its potential level of GDP, and that core inflation will be above 2% by the end of this year, we’d call that substantial progress. As such, would it really be necessary for the Fed to keep the policy rate at the zero-bound at that point? The recovery will already be close to completion, offering an opportunity to pivot communication and signal an easing of asset purchases before the end of 2021.

This provides some upside for our yield forecast. The last time the Fed signaled an adjustment to its QE policy in 2013, the UST 10-year yield shot up 132 basis points in just 4 months (also known as the taper tantrum). At the time, the Fed was just hinting of an end to new purchases, it wasn’t even debating an unwind of its balance sheet. The point here is that an adjustment to QE policy acts as a strong forward guidance signal and investors will quickly price higher yields as a result.

This time around, the 10-year yield has already jumped 122 basis point from the August 2020 low. That is a big move without any signal from the Fed that it will tighten policy. Now we don’t expect an additional 100 basis points tacked on once the communication adjustment to QE policy occurs, but some volatility is likely to occur and the UST 10-year could reach 2% quicker than previously thought.

What Does this Mean for our Yield Outlook?

Our readers know that the driving force behind the rise in government bond yields over the last eight months has been the rise in inflation expectations and the anticipation of an earlier start to the central bank rate hiking cycle. For the Fed, given our expectation that it will hike at the end of 2022 and eventually get the effective policy rate to 1.85%, the fair value of the UST 10-year yield is around 1.7% to 1.8% today. We see the 10-year rising to our long-term target of 2.5% over the next couple of years, although as we note above, the speed of adjustment is a wild card.

With the UST 10-year yield currently trading around 1.6%, that is just a little lower than our estimate of fair value. When we break down this yield into the path for rates and the term premium, we calculate that just over 40% of the 10-year’s yield is due to Fed policy rate path expectations. The rest is investors demanding compensation for the risk that inflation will overshoot and that the Fed may surprise the market with more rate hikes. In other words, investors aren’t banking that the Fed will raise rates as high as we think it will, but long-term bond investors want more compensation for this risk.

Bottom Line

The economic recovery continues to show incredible resilience. GDP and employment are quickly closing in on their potential. Inflation will follow suit. The Fed is recognizing this upturn in the economy, but has been hesitant to change its tune on its policy stance. Should the recovery continue to unfold as we predict, the balance of risks will shift from a zero-policy rate designed to stoke the recovery, to one that if left unchecked for too long, will fail to mitigate financial and economic risks. And, it’s important to note that there are still many unknowns related to the outlook that are not uniquely positioned to the downside anymore. The Biden administration has put forward the American Jobs Plan at just over $2 trillion, and later today there will be more details released on other measures to redistribute income and social programs towards the middle and lower income groups of America. None of these have been baked into the economic and financial outlook. Yet, both could lead to higher longer term yields and an earlier exit from ultra-low rates by the Federal Reserve.

Recent U.S. economic data are serially exceeding expectations. From the ISM manufacturing and service data that reveal not just resilience but power, to households that reflect a strong appetite to spend their government stimulus checks, to employment gains that signal more of the same is to come in the months ahead. The determination of the U.S. economic rebound cannot be denied – a sentiment echoed by Federal Reserve Chair, Jay Powell, when he stated that the economy is “at an inflection point.” With fiscal stimulus in place and vaccine supply to soon outstrip demand, the U.S. economy is rapidly absorbing any remaining slack. In the months ahead, evidence will mount to support the reflation narrative, prompting Fed members to adjust their forward guidance to signal an earlier rate hike cycle and an end to Quantitative Easing (QE).

Recent U.S. economic data are serially exceeding expectations. From the ISM manufacturing and service data that reveal not just resilience but power, to households that reflect a strong appetite to spend their government stimulus checks, to employment gains that signal more of the same is to come in the months ahead. The determination of the U.S. economic rebound cannot be denied – a sentiment echoed by Federal Reserve Chair, Jay Powell, when he stated that the economy is “at an inflection point.” With fiscal stimulus in place and vaccine supply to soon outstrip demand, the U.S. economy is rapidly absorbing any remaining slack. In the months ahead, evidence will mount to support the reflation narrative, prompting Fed members to adjust their forward guidance to signal an earlier rate hike cycle and an end to Quantitative Easing (QE).