Fiscal Stimulus and Elevated Debt:

A New Chapter for The Canadian Economy

Sri Thanabalasingam, Senior Economist | 416-413-3117

Omar Abdelrahman, Economist | 416-734-2873

Date Published: May 3, 2021

- Category:

- Canada

- Government Finance & Policy

Highlights

- In an eventful spring budget season, the federal and provincial governments kept spending spigots open to a greater degree than what we had anticipated in our latest March forecast. We estimate that this additional stimulus could translate into a real GDP boost of 0.3-0.6 ppts this year and 0.4-1.0 ppts next, with the 2022 impact much less certain.

- While temporary COVID-19 supports dominate near-term spending plans, the spring budgets did mark some shift in the spending mix towards more longer-term initiatives.

- Despite elevated debt burdens, expectations for continued low interest rates are projected to keep a lid on debt service costs. However, this has left the country with less fiscal space to respond to another economic crisis.

- Making good on medium-term budget targets and committing to allocate any unanticipated budget windfalls towards debt reduction will help to sustain credit ratings and keep borrowing costs low. In addition, a re-orientation of the spending mix towards productivity-enhancing projects will also support longer-term fiscal sustainability.

A flurry of government programs – from income supports to rent subsidies to sickness benefits -- have been crucial in supporting the economy through the pandemic. With Canada caught in the grips of a third virus wave, the federal and provincial governments faced increasing pressure in this year’s spring budget season to provide further assistance to households and businesses to bridge them to the other side of the crisis.

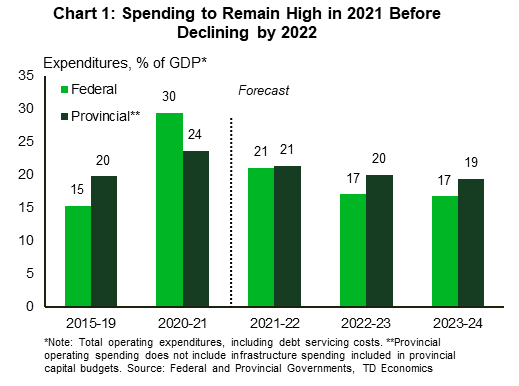

In response, governments tabled 2021 budgets that indeed keep the spigots open. After reaching close to 30% of GDP in fiscal year (FY) 2020-21, federal spending is projected to remain historically elevated at 21% of GDP in FY 2021-22, before falling somewhat closer to pre-pandemic trends in FY 2022-23 and 2023-24 (Chart 1)1. With the federal government shouldering the bulk of the overall COVID-19 response, provinces will see a swifter return back towards pre-pandemic spending trends. However, this masks a ramp-up in public capital investment plans that are not accounted for in their operating balances.

As the 2021 budget round draws to a close, temporary COVID-19 supports continued to dominate near-term spending plans. This deficit spending, which builds on previous commitments made by governments earlier in the pandemic, will add significantly to economic growth this year and next. That said, a number of governments elected to shift some of the new spending balance in their recent budgets towards longer-term initiatives, such as childcare. However, the economic impact of these measures is less certain. With many of these initiatives back loaded into the medium term, some projects may not ultimately see the light of day and those that are carried out may not necessarily boost Canada’s economic capacity.

Relatively elevated spending plans will increase Canada’s debt burden, which has already ballooned so far during the pandemic. Few governments committed to an explicit fiscal anchor within their medium-term plans. Most have either offered expected timelines for balancing their budgets or an implicit trajectory that includes gradually declining deficits and debt burdens.

In an international context, Canada’s federal debt burden remains relatively low. However, adding aggregate provincial debt changes the picture and lifts overall obligations considerably, both on a GDP or per capita basis. As a result, Canada now has less fiscal space to respond to another economic crisis. In addition, an unanticipated sharp increase in interest rates could mean significantly higher debt servicing costs. Taking action to mitigate against these longer-term fiscal risks will be crucial once the pandemic is behind us. Commitments such as returning any unanticipated budget windfalls to paying down existing debt would go a long way in providing investors with greater confidence in Canada’s fiscal future. But, above all, a greater tilt in the focus of spending towards investment (rather than consumption) will be necessary.

Pandemic Supports Tip the Scale for Spending Levels…

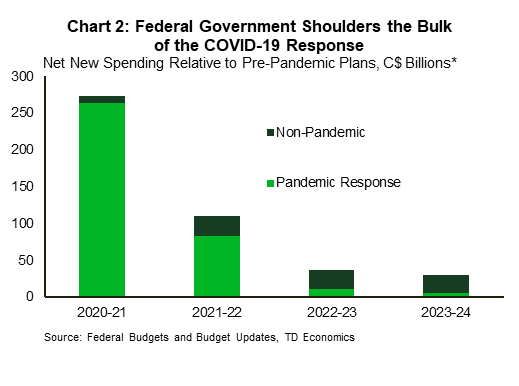

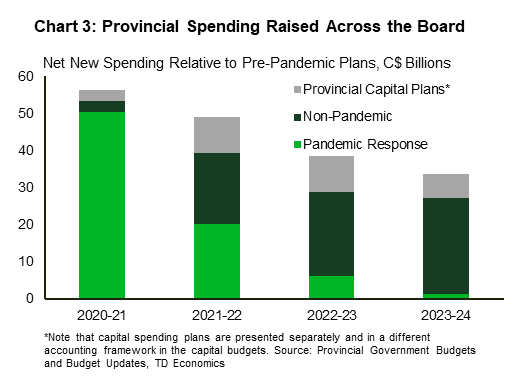

Tallying up the measures announced since the pandemic began early last year points to a sizeable lift in the planned level of spending. Charts 2 and 3 show how government outlays have evolved relative to governments’ medium-term forecasts ahead of the pandemic. Combined spending of the two levels of government overshot pre-pandemic expectations by a massive $630 billion over four years (after accounting for increases in federal transfers), with much of that front loaded to this past fiscal year (2020-21) when temporary pandemic supports are expected to have hit a peak2.

Still, the persistence of more elevated spending is evident. Outlays for the current fiscal year are expected to tip the scales some $160 billion above pre-pandemic plans before easing to a still significant $75 billion next year.

In terms of near-term pandemic supports, the federal government has shouldered much of the heavy lifting and announced further extensions of programs in Budget 2021. At the provincial level, healthcare spending to tackle pandemic-related challenges has taken the biggest piece of the pie, but there were notable pledges in other areas. These included income support top-ups, childcare supports, small business grants, and transfers to municipalities struggling with low transit ridership.

…But Non-Pandemic Spending Also Raised

Despite the urgency to provide pandemic-related supports to both households and businesses, an important share of the spending announced during the pandemic has still been dedicated to longer-term spending initiatives. We estimate that around 20% of the federal government’s net new spending announced during the pandemic for FY 2020-21 to FY 2023-24 has been dedicated towards longer-term, non-pandemic initiatives. In contrast, around 45% of net new spending at the provincial level since the start of the pandemic has been earmarked to what governments labelled “pandemic response” or “time-limited response”, meaning that a little over a half was devoted to other -- largely longer-term -- initiatives, including upwardly revised capital spending plans.

One example of these longer-term programs announced in the federal budget is the additional income support for seniors over the next five years. At the provincial level, almost all governments increased general health outlays, with mental health receiving significant attention in some provincial budgets. Some provinces increased funding to K-12 education, higher education, and job training. Among the notable policy measures, Ontario increased funds earmarked for long-term care homes in its medium-term plan.

Beyond these measures, the budgets also contained some new policy measures that could lift Canada’s economic potential over the long-run. At the federal level, the key undertaking was a new childcare policy. At a cost of $30 billion over the next five years, the policy – which is designed as a cost-sharing program with provinces – intends to lower childcare fees by 50% by 2022 and increase labour force participation. Other productivity-enhancing measures initiatives include additional climate-related commitments, infrastructure spending, investments in biomanufacturing and life sciences research, artificial intelligence, and genomics, as well as funding digitization in small businesses.

At the provincial level, the centerpiece of the stimulus response was on infrastructure. Provinces revised up capital plans significantly for FY 2021-22 and 2022-23 (Chart 3). This spending is not targeted, but instead spread throughout traditional infrastructure projects: transit, healthcare, schools, and highway construction. Provinces also dedicated some spending to broadband infrastructure, with more modest outlays to climate-related initiatives.

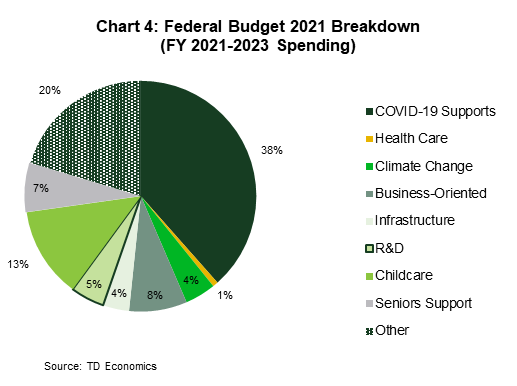

New Stimulus in 2021 Budgets To Boost Growth In the Near-Term, Less Certain Over Longer Run

The persistence of more elevated government spending than we had previously expected represents an upside risk to our March economic growth forecast for Canada. To gauge an estimate of measures on our forecast, we zero in on net new announcements that were made in the latest budgets that weren’t already included in latest projections (see Chart 4). Combined, our ballpark estimate of federal and provincial government announcements tallies up to around $150 billion in additional spending over the next three years (after removing net new federal transfers). On the face of it, this represents a significant degree of medium-term stimulus. From a federal perspective, the 2021 budget unveiled new spending at the top end of the $70 to $100 billion range that was signalled in its Fall Economic Statement last year. (Given the lack of details, we did not include this in our baseline forecast in March.) The remaining $50 billion in unanticipated spending over three years was at the provincial level, where the legacy of the crisis has prompted some jurisdictions to ease up on restraint imbedded in their previous plans. Instead, as noted earlier, budgets call for spending increases in the coming years with some provinces boosting outlays more than others. Some governments, like Ontario, had already announced a bigger part of the lift in the late fall.

Predicting the impact of fiscal spending on growth is challenging. For one, the timing of the spending may not line up with when funds are booked not to mention uncertainty around multiplier impacts. However, we calculate that new federal-provincial budget measures earmarked for 2021 could translate into a real GDP boost of 0.3-0.6 ppts this year.

But beyond 2021, there is considerably more uncertainty around potential economic impacts. When will programs be initiated? Will there be hiccups in getting initiatives like national childcare off the ground? Could elections force a change in priorities? If the bulk of additional spending planned for 2022 takes place next year, real GDP growth could be as much as 0.4-1.0 ppts higher relative to the profile in the absence of this new stimulus. But if spending is backloaded, the growth benefits would only be seen in 2023 and beyond.

It will be important for policymakers to follow through on productivity-enhancing projects. The national childcare program, infrastructure projects, and investments in research and development all have the potential to increase the economy’s capacity over the long run. For example, a national childcare program could increase Canada’s labour force by 1% by enabling more women to enter the labour market. All things equal, investment in infrastructure would reduce the cost of doing business and greater research and development funding would support longer-term productivity and help to ease Canada’s long-standing competitiveness challenges.

The implementation of these measures may not be easy. For the national childcare program, federal negotiations will need to take place with the provinces, who will be required to share half of the costs. With provinces facing more pressing fiscal constraints, it remains an open question as to how this will be achieved. Meanwhile, spending on infrastructure and R&D could be moved to the backburner as other priorities emerge, including a post-budget pledge to increase healthcare transfers to the provinces.

The contribution to the supply side from these productivity-enhancing measures would reflect in higher federal and provincial revenues, lessening the fiscal impact of these up-front investments over time. Put another way, boosting the economy’s growth potential would help Canada counter the rapid buildup in debt that has made the country more vulnerable to future economic shocks.

Higher Deficit and Debt Levels Across the Country

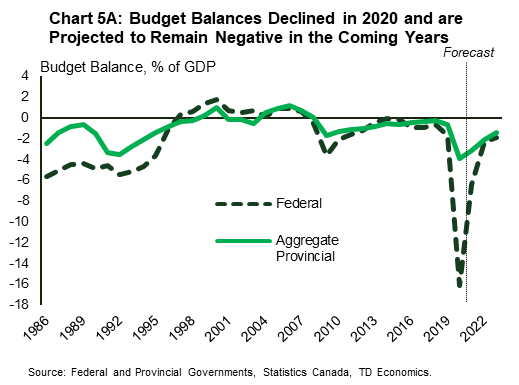

The pandemic imposed extraordinary unplanned expenses in 2020 that ballooned provincial and federal deficits. The federal deficit has deteriorated a lot more than those at the provincial level because it bore the brunt of the costs associated with the health crisis (Chart 5A). The federal budgetary deficit ballooned to 16.1% of GDP in FY 2020-21, while the aggregate federal-provincial deficit stood at around 20%.

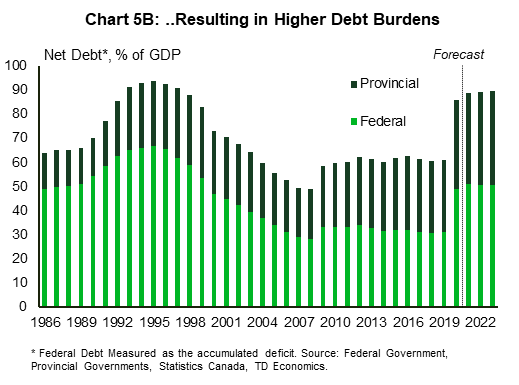

Across the country, budgetary balance projections contained in the 2021 budgets remain in negative territory over the next few years, leading to elevated debt burdens for both provincial and federal governments (Chart 5A; Chart 5B). On average, as a percent of GDP, the aggregate provincial budget balance is expected to run at around -2.2% from FY 2021-22 through to FY 2023-24, while at the federal level, the metric is projected to be -3.5%. However, in both cases, the deficit forecast does decline over time. Translating deficit into debt terms, aggregate net provincial debt is expected to stand at 38.5% of GDP, and the federal debt at 50.8% over FY 2021-22 to 2023-24.

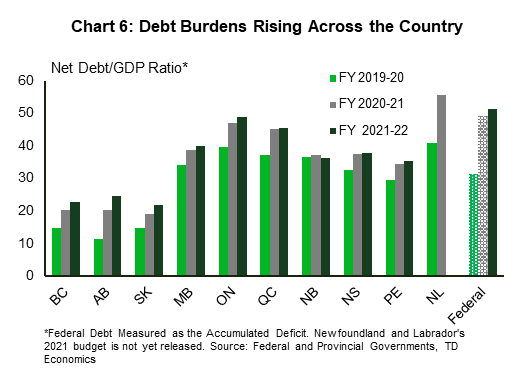

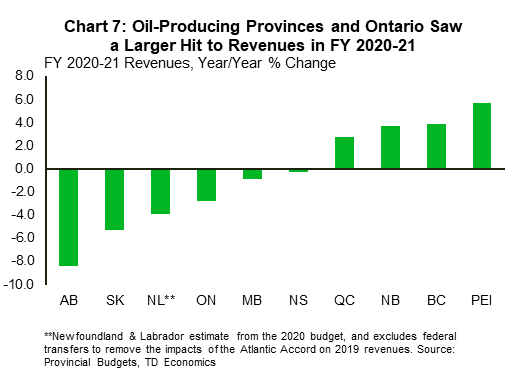

At the provincial level, debt burdens have risen across the board (Chart 6). Alberta, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Ontario have seen the largest jumps. These provinces were facing structural deficits prior to the pandemic, and the health crisis worsened the situation. Being one of the provinces most impacted by the pandemic, Ontario’s higher caseloads and longer-lasting restrictions weighed more on revenues (Chart 7). Alberta and Newfoundland, in addition to spending more, were hit hard by a slump in oil revenues earlier in the pandemic. Meanwhile, B.C. and Saskatchewan entered the crisis with far lower debt burdens and have kept their operating spending taps open while stepping up their capital spending. Accordingly, these are among the few provinces whose deficits are expected to increase this year over last, while they likely see some erosion in their debt positions relative to other provinces. Quebec’s debt burden also increased relative to last year. Its budget balances, however, suffered a lesser hit than most others (save the Maritimes and Manitoba). Own-source revenues saw a smaller decline. A larger share of federal transfers in total revenues helped provide a backstop to the province’s finances.

The last time the combined federal-provincial debt burden was this high was in the early 1990s, when Canada underwent a budget crisis. During this period, policymakers instituted large spending cuts and tax increases to tame deficits and bring the budgetary balance into surplus territory. Governments exercised fiscal discipline through the second half of the 1990s and into the 2000s to gradually lower the debt burden to more sustainable levels. Canada stood out like a sore thumb on the global landscape back then, which is not the case today.

Supporting the economic recovery and building economic capacity over the medium term will weigh on governments’ finances, but these pressures are likely to wane, and budget shortfalls will lessen over time. Most provincial governments provided a timeline by which they intend to balance their budget (Table 1). At the earliest, Nova Scotia intends to return to black ink by FY 2024-25. Meanwhile, other governments do not anticipate balanced budgets prior to FY 2025-26, with Ontario delaying its plan to balance to FY 2029-30 and B.C. expecting a return to black ink between 2028-29 and 2030-31. However, nearly all provincial governments provided little detail on how these targets would be achieved. Only Alberta and Ontario made mention of fiscal anchors, with emphasis on keeping the net debt to GDP ratio below 30% and 50.5%, respectively. Cautious economic assumptions may allow for positive surprises in budget balances, but provinces with pre-existing structural deficits will face a more difficult time returning their books to black ink.

From a federal perspective, the government made a commitment to reduce the federal debt as a share of the economy over the medium term. The government forecasts that the debt-to-GDP ratio will decline from 51% in 2021 to 49% of GDP by 2025. A steady trend reduction in spending along with stable revenue gains, contribute to this result. Still, the debt burden would stand nearly 20 percentage points higher than what it was prior to the pandemic partly given the laundry list of spending programs enacted in the 2021 federal budget.

Low Interest Rates Help Maintain Sustainable Debt Burdens

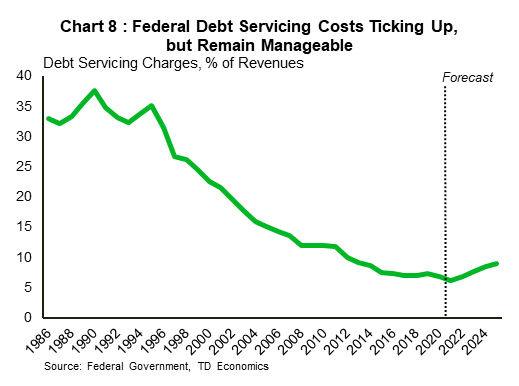

Although debt burdens are likely to be elevated, Canadian governments are expected to benefit from continued low interest rates that should help to put a lid on the cost of borrowing. Unlike the 1990s, when debt servicing costs were above 30% of revenues, the charges are now considerably lower due to historical low interest rates (Chart 8). In 2020, aggregate debt servicing costs stood at 7% of revenues.

This was broadly the same for provinces as well as the federal government. However, some provinces are seeing more upward pressure, namely Newfoundland and Labrador (near 15% in FY 2020-21). Although not alarming yet, Ontario’s interest bite is expected to gradually increase to 9% of revenues by FY 2024-25, the highest behind Newfoundland and Labrador.

Budget forecasts for continued relatively low debt servicing costs imply that the debt burden – though elevated – will remain sustainable without the need for large tax increases. However, crucial to this assumption is that economic growth will continue to exceed the effective borrowing rate in the years ahead. This will be the true test. Indeed, almost all budgets contained little in the way of new tax-generating measures. Budget planners have assumed that interest rates will be pressured only gradually higher over time, as economic slack is steadily removed from the landscape. This also presumes that governments can hold to their stated expenditure commitments and resist any temptation to overshoot. Clearly, there are risks on all sides.

Acknowledging that interest rates may not stay as low as they currently are, the federal government stated in the budget that it will increase the average maturity of its borrowing, moving a greater share of bond issues to the long end of yield curve. This will lock in lower interest rates for longer and reduce the risk brought on by debt rollovers. Provincial government borrowing already tends to be long-term in nature.

While low interest rates ease the financial cost of carrying large levels of debt, they do not provide governments with the license to embark on a prolonged spending spree in the years ahead. If governments opt to move away from their stated expenditure plans and/or spend inefficiently, the debt burden would inevitably increase. This could unnerve investors and lead to a faster-than-expected climb in interest rates and further increase in debt-to-GDP ratios.

Table 1: Fiscal Commitments in 2021 Budgets

| Province | Fiscal Commitment |

|---|---|

| British Columbia | - Budget balance between FY 2028-29 and FY 2030-31 |

| Alberta | - Net debt to GDP ratio to remain below 30% - Per capital spending lowered to levels in other large provinces |

| Saskatchewan | - Budget balance by FY 2026-27 |

| Manitoba | - Budget balance within eight years - Net debt to GDP ratio implicitly peaks at 39.9% |

| Ontario | -Net debt to GDP ratio to remain below 50.5% - Budget balance by FY 2029-30 |

| Quebec | - Budget balance targetted by FY 2025-26, but plans to eliminate shortfall not yet announced - Net debt to GDP ratio implicitly peaks at 45.5% |

| New Brunswick | - Net debt to GDP ratio already peaked in FY 2019-20 |

| Nova Scotia | - Budget balance by FY 2024-25 |

| Prince Edward Island | - Net debt to GDP ratio implictly peaks at 35.4% |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | - N/A |

Potential Perils Up Ahead

Indeed, the road ahead is rife with potential risks for government finances. In the near-term, the risks are more likely to the upside. Cautious assumptions on economic growth and contingencies, particularly from provinces, leave room for a fiscal outperformance in 2021. If revenues do come in stronger than expected, it would be prudent for policymakers to either use windfalls to paydown debt loads or invest in projects that generate the greatest return on long-run economic growth, and therefore revenues. This would provide Canada with more fiscal space in case we are faced with another economic crisis.

Typically, past recessions have increased Canada’s federal debt burden by 10 percentage points. The health crisis has already lifted this by 20 percentage points. Without making a larger dent in the existing debt burden, Canada may have to borrow at considerably higher interest rates to implement counter-cyclical fiscal policy, thereby racking up larger deficits. To avoid this outcome, federal and provincial governments should borrow a rule of thumb from good management of personal finances. That is, commit to allocating a share of any potential revenue windfalls to paying down the debt burden and resisting expenditure accelerations. There is likely little wiggle room left in debt burdens in the eyes of investors. Debt management now becomes an issue of credibility to maintain high credit ratings. According to most government budget projections, deficits will decline sharply from their 2020 highs, and most have outlined plans – further away in the horizon as they may be – to balance their budgets. Policymakers will have to commit to these targets in order to hold onto their ratings. Further loosening of the purse strings, however, could lead to downgrades and rising borrowing costs.

As of now, rating agencies remain optimistic on Canada. Recently, S&P Global Ratings reaffirmed its AAA rating, stating that Canada’s strong fiscal position coming into the pandemic helped moderate the effects of the pandemic and that the “deviation from the government’s fiscal profile does not offset Canada’s structural credit strengths”. Still, the rating agency cautioned that if the fiscal situation worsens or is prolonged, a downgrade could be in the cards.

Concluding Remarks

This spring budget season has been unlike any other. After unveiling extraordinary spending measures in 2020, governments plan to keep funds flowing this year to bridge households and businesses to the other side of the pandemic. However, policymakers do not currently plan on tightening purse strings much in the following years thanks in part to growing revenue from a steadily improving economy.

The pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in areas of the country that require upgrading like health systems and long-term care homes. Childcare needs, as well, were highlighted during the health crisis. In addition, traditional infrastructure areas like roads, schools, and transit require attention. Across the country, governments clearly documented that they will work towards addressing these needs in the coming years.

But these useful spending ventures won’t come cheap. Reflecting this, budgets are building in several years of elevated debt burdens. Currently, low interest rates will help maintain debt loads, but the considerably higher level of debt compared to pre-pandemic times suggest Canada has less fiscal space to respond to the next economic crisis.

Commitments such as returning windfalls to paydown debt could more quickly reduce debt loads. It would also boost investor confidence. This could set up Canada for less fiscal worries as the economy enters a new chapter in the post-pandemic period.

End Notes

- This includes program spending and debt servicing costs (i.e. total operating spending). It excludes provincial capital spending plans. Newfoundland and Labrador has not yet released a budget in 2021. Assumptions are made on the trajectory of its spending to complete the provincial aggregate.

- We calculate rough estimates of net new spending relative to pre-pandemic plans by comparing total expenses in the 2021 budgets to the latest budgetary plans available prior to the pandemic for each government. Note that the date of the pre-pandemic plan will vary depending on the government. Some governments tabled plans that did not incorporate the impacts of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 (or had announced only modest responses relative to current spending). For others that published their full budgets later in 2020, the latest pre-pandemic plans will date back to 2019.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: