Corporate Canada Is Getting On Board

An Update Since Comply or Explain Gender Disclosure Policy Came Into Effect

Beata Caranci, Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

Leslie Preston, Senior Economist | 416-983-7053

Research assistance provided by:

Mo Bakri, Research Analyst

Oriana Kobelak, Coordinator

Date Published: March 27, 2019

- Category:

- Canada

- Diversity & Social Studies

In 2013, we wrote a report titled “Get on Board Corporate Canada” that called out the lack of progress of women on the boards of publicly traded Canadian companies. Despite women’s progress within the labor market and increased educational attainment, there was no evidence of the same at the board level. Within the international rankings, Canada had also fallen behind countries that had implemented formal diversity policies. This had a whiff of market failure.

In response, we recommended the adoption of a “comply or explain” board disclosure policy in order to mobilize shareholder market forces by creating accountability, transparency and measurability of board selection and diversity practices. Canada’s largest securities regulator, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), agreed with this approach. In 2014, the OSC introduced comply or explain (C/E) disclosure that came into effect in 2015. This requires most companies listed on the S&P/TSX to disclose the number and proportion of women on their boards and in executive officer positions. It also requires disclosure on whether there is a policy related to the identification and nomination of women directors, how the company considers the representation of women in the board nomination and executive officer appointments processes, and whether there are adopted targets at either the board or executive officer level. Choosing to do none of the above requires an explanation.

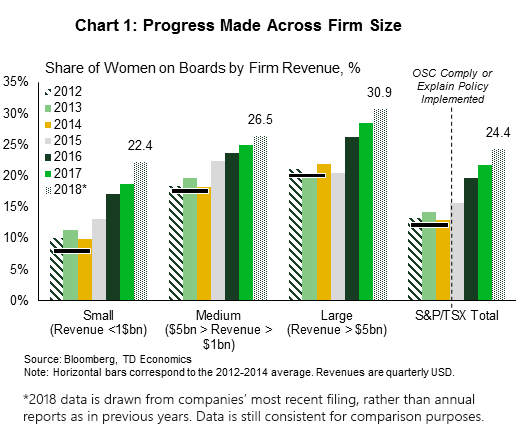

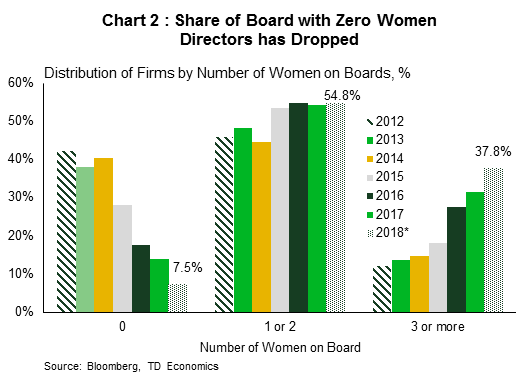

With only four years since the policy came into effect, it has been highly effective in a number of areas. First, there has been a notable increase in the share of women on boards across all industries and across all firm sizes. Second, there has been a rapid decline in the share of boards with zero women. Third, comparing across countries, C/E disclosure policies appear as effective at increasing women on boards as quotas, with the passage of time.

However, corporate Canada’s journey is not yet complete. Most publicly traded companies fall short of the important minimum 30% threshold that constitutes critical mass. Continued progress must be made by smaller firms, which account for 63% of the board seats on the S&P/TSX. In addition, C/E policy has not compelled an improvement in the representation of women within the senior executive rankings of firms. A similar outcome was also noticed with countries that mandated diversity quotas.

Institutional shareholders are increasingly acting on the information that C/E disclosures provide in order to influence companies towards greater gender diversity. A number of these measures have only been recently implemented (see Appendix A and B). More time is likely needed to measure the combined effectiveness of the policy and shareholder initiatives. However, vigilance will be required to ensure a “hit the number” phenomenon doesn’t take hold. This might be in the form of appointing a couple of women to board seats in order to avoid investor scrutiny. Or, when there’s a belief that diversity is accomplished with only one or two women. This skirts fundamental change within candidate selection and searches.

TD’s 2013 Report - Rationale for Comply or Explain Policy

When we investigated solutions to address Canada’s poor board diversity record within the S&P/TSX, there was a clear divide between countries championing hard lined quota-based systems versus those preferring a more market-driven C/E disclosure policy. Quotas mandating the share of women of boards were gaining popularity within a number of European countries, acting as a blunt (but effective) tool for altering gender representation. However, they came with greater risk of unintended consequences. In particular, quotas ran afoul of harnessing market and economic forces to address root causes like biases or candidate search and nomination practices. In addition, quotas risked stigmatizing qualified women on a corporate board by carrying the perception of being the antithesis of merit.

In contrast, C/E disclosures gave shareholders the tools to hold firms accountable on gender diversity at the board and senior executive level. We preferred this policy since it rejects a one-size-fits-all approach and mitigates some of the downside risks related to non-market solutions. In addition, there was evidence of progress occurring within Australian and UK publicly listed firms, which were early-adopters of versions of C/E policy.

With the OSC enforcing a C/E disclosure rule in 2015, this was essentially opting for a carrot rather than a stick approach to incentivize boards and shareholders to challenge their views and practices on gender diversity. However, like any regulatory or public policy initiative, measuring progress is fundamental in assessing its effectiveness and whether any adjustments are needed.

Broad based progress since 2015

A picture says a thousand words. Chart 1 shows a clear acceleration in the share of women on S&P/TSX corporate boards post-2015. Prior to that period, the shares moved around ever so slightly from year-to-year, but came up against a low ceiling, particularly when it came to smaller sized firms. In fact, this group has shown the greatest transformation, with a doubling in female board representation in just four years, after virtually no movement in the three years preceding the policy. Looking at the data in a slightly different manner captures another notable area of improvement. There has been a rapid collapse in the share of firms with no women on their boards (Chart 2). In 2014, 40% of the firms on the S&P/TSX had zero women on their boards, a share that had not moved in at least three years. This stood at less than 10% in 2018.

On the international stage, Canada has stabilized its place in the rankings (Table 1, page 3). This data uses a more narrow set of firms relative to our S&P/TSX measure. When we wrote the original paper in 2013, the international benchmark was 2011 data, in which Canada ranked higher than it does today, but did so with a much lower female board representation of just 13%. A doubling of this figure has allowed corporate Canada to keep pace with peers, but not leapfrog their progress, as more countries are also making inroads with the aid of gender diversity policies.

| Table 1: % of Women on Boards of Directors | |||||||||

| Top 15 Countries Among Industrialised Economies | |||||||||

| 2009 | 2011 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |||||

| Norway | 35.7% | Norway | 36.3% | Norway | 39.4% | Norway | 42.2% | France | 41.2% |

| Sweden | 23.8% | Finland | 26.4% | France | 37.6% | France | 40.8% | Norway | 39.6% |

| Finland | 23.5% | Sweden | 26.4% | Sweden | 35.6% | Sweden | 37.7% | Sweden | 36.9% |

| Denmark | 13.9% | France | 16.6% | Italy | 33.1% | Italy | 35.8% | Italy | 35.0% |

| Netherlands | 13.2% | Denmark | 15.6% | Finland | 30.2% | Finland | 33.7% | Finalnd | 34.5% |

| Canada | 12.4% | Australia | 13.8% | New Zealand | 29.6% | Belgium | 30.4% | Australia` | 31.5% |

| USA | 12.1% | New Zealand | 13.7% | Belgium | 27.7% | New Zealand | 30.0% | Belgium | 31.1% |

| New Zealand | 12.0% | Canada | 13.1% | Australia | 26.0% | Australia | 28.7% | New Zealand | 30.2% |

| Germany | 10.5% | Netherlands | 13.1% | UK | 25.3% | UK | 26.8% | UK | 29.1% |

| Ireland | 9.1% | Germany | 12.9% | Canada | 22.8% | Canada | 25.8% | Canada | 27.0% |

| France | 9.0% | USA | 12.6% | Israel | 21.8% | Spain | 24.0% | Netherlands | 24.9% |

| Switzerland | 8.9% | Austria | 10.8% | Austria | 20.9% | Denmark | 23.6% | Israel | 24.5% |

| UK | 8.5% | UK | 10.7% | Denmark | 20.9% | Israel | 23.1% | Ireland | 24.0% |

| Australia | 8.4% | Spain | 10.2% | Spain | 20.6% | Switzerland | 22.3% | Denmark | 23.7% |

| Hong Kong | 8.2% | Hong Kong | 9.4% | Ireland | 20.4% | USA | 21.7% | Spain | 23.6% |

| Source: MSCI Reports, TD Economics | |||||||||

One of the criticisms some offer on board policies that target gender diversity is that it may cause a phenomenon called “overboarding” or sometimes referred to as the “golden skirt” in specific reference to women. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), a proxy advisor firm, defines “overboarding” as the same individual sitting on more than four boards. This stigma against women may have become rooted during the early years of Norway’s quota implementation, when there was some concern of a small number of women occupying a large number of board seats. However, this phenomenon is not unique to women and has declined significantly in recent years under increased board workloads and shareholder scrutiny. Within Canada, a 2017 report by the Rotman School of Management identified 16 directors as sitting on four or more corporate boards – six women and 10 men. These overboarded female directors represent only 5% of the total of women-occupied board seats. The same seems to be true in other countries with C/E policy like Finland or Sweden, which have both crossed the 30% threshold on women’s board representation1. In the U.S., which lacks a C/E policy, the rate of overboarding among female directors has also decreased, even as the number of female board members has grown2. So this “golden skirt” concern falls into the camp of an overstated bias or urban-myth.

Carrot Versus Stick

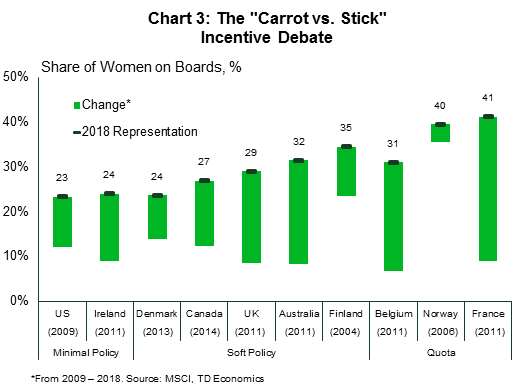

To further understand the effectiveness of C/E policies relative to other choices, we grouped a sample of advanced countries according to the type of board diversity policy (Chart 3). Stringency increases moving from left to right on the chart, with quotas defining the most stringent criteria. By comparison, C/E or similar are characterized as “soft policy”. In the nomenclature of economics, this is the distinction of a stick versus a carrot incentive structure.

At the far left of the chart, two countries are characterized as having minimal policy. In the U.S., the SEC requires companies to disclose whether, and if so how, nominating committees considered “diversity” in the process of identifying director nominees. This includes disclosure of any related policies, how the policies are implemented and how the nominating committee or the board assesses the effectiveness of such policies. The SEC does not, however, define the term “diversity”, letting companies make their own determinations. This offers a lot of scope for a firm to characterize diversity under a broad definition, such as educational and professional background, rather than gender. Ireland also gets captured as having minimal policy since it lacks a quota or disclosure requirement. But, they did set a voluntary 25% target, with a warning that quotas would be considered if improvement was deemed insufficient. This reflects a carrot approach, with the “stick” threat overhanging the incentive structure.

A couple of features pop out on Chart 3. First, it’s not conclusive that hard or soft policy accounts for a meaningful statistical difference in the progress. Interestingly, Australia and Belgium have made a similar amount of progress despite very different approaches. Those companies that face a quota, will hit the quota when there are penalties for not meeting that requirement. Penalties vary by country, but can range from delisting in Norway to denying directors’ compensation in Belgium and France. Where the quota is set is where firms will land on female board representation, but no more than that. This is somewhat suspicious as to whether culture and practices have indeed been influenced. Norway was the poster-child on a 40% quota that was set a decade ago, and the share has not moved above that level.

Second, time seems to be one differentiator. Board seats turn over slowly to ensure institutional knowledge and firm stability. As such, the amount of time that a policy has been in place does matter. Both Australia and the UK had a three-year head start on Canada with their disclosure policies, so it is not surprising that they are farther ahead on progress.

Revisiting Canada’s trouble spots

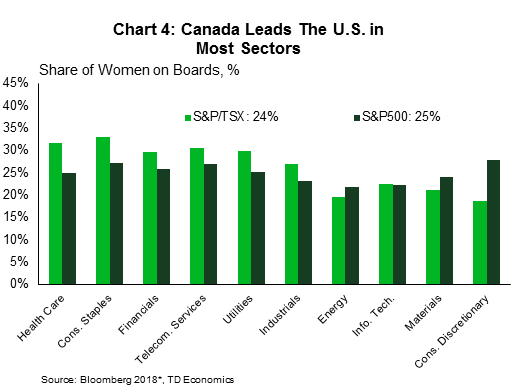

In a demonstration of the effectiveness of Canada’s C/E policy, it’s useful to compare the speed of adjustment in board gender diversity relative to that in the United States, which has the lowest bar on disclosure. Both countries had weak or lacked diversity disclosure policy when we first conducted this analysis with 2011 data. We found that Canada lagged the U.S. on every metric. The S&P500 demonstrated higher female board representation by firm size and within almost every industry. In fact, regarding the latter, the U.S. outpaced Canada in a whopping eight out of ten industries, and often by a large margin.

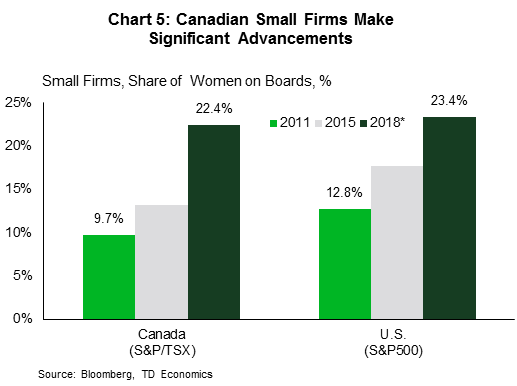

The 2018 data demonstrates that the tables are turning. Canada now outperforms the U.S. board gender representation in seven of those same ten industries (Chart 4). When it comes to small-sized firms where Canada has an overweight share, female board representation has increased 12.7 percentage points between 2011 and 2018, compared to 10.6 percentage points in the U.S. (Chart 5).

Canada’s Corporate Journey Is Not Complete

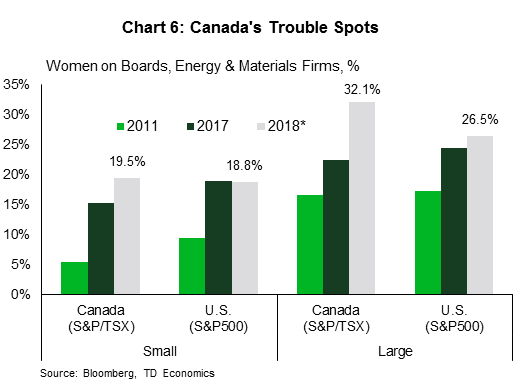

So why then does the S&P/TSX still show lower aggregate female diversity at 24%, relative to the S&P500 at 25%? This harkens back to the findings we presented in our 2013 report that uncovered that the TSX’s unique resource-heavy industry structure combined with a high prevalence of smaller companies create a stronger headwind for women on boards. Smaller sized firms generally have fewer board seats, which will turn over more slowly and limit hiring opportunities to challenge the status quo. In addition, smaller sized firms are more likely to cite limited resources for candidate searches and securement.

Within the S&P/TSX, 72% of firms were characterized as small-sized in 2018, versus just 20% on the U.S. equivalent benchmark. In addition, Canada’s benchmark is heavily weighted to the resources sector (i.e. energy and materials). Combining the two impacts, small-sized resource firms capture 30% of all board seats on the S&P/TSX, compared to just 12.5% in the U.S. benchmark. So, even though Canada’s large and small resource firms are both outperforming their American peers (Chart 6), the simple math keeps Canada trailing within the aggregate measure.

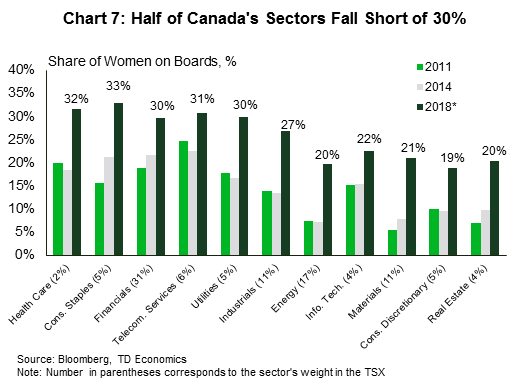

This is a reminder that although Canadian publicly listed firms have made great strides on gender diversity in a few short years, the journey is far from over. The next phase of improvement in board representation will materially rest on the shoulder of small-sized firms that account for 63% of board seats, with a particular lean towards those in the energy and materials sectors (Chart 7).

We estimate that if the small energy and materials firms bumped up the share of women on their boards to just 25%, this would move the dial on the S&P/TSX as a whole to 26%, from 24.4%. However, research shows that having a minimum of three women on a board represents a tipping point in terms of influence and financial performance3. This is because the minority gain a reasonable level of critical mass where contributions cease being representative of that particular group, and begin to be judged on their own merit.

If all of Canada’s small-sized firms were to hit the tipping point of three women on their boards, it would single-handedly move the entire S&P/TSX up by ten percentage points to 34%. This underlines the importance of improvements at small firms to meet metrics on critical mass and greater diversity. The largest of Canada’s firms, even in the traditional male-dominated resource sector, are already at this minimum guidepost.

More time needed for market forces to work

A key feature of the C/E disclosure requirement is that it gives the market the information needed to challenge companies about their governance practices. For the boards of publicly traded companies, the market is their shareholders. Institutional investors in Canada and the U.S. are increasingly pushing harder for greater representation of women on boards as the data begins to speak for itself. For example, in September 2017, the 30% Club Canadian Investor Group4 issued a statement of intent declaring that their objective is to achieve a minimum of 30% women on the board and at the executive management level for the S&P/TSX composite index of companies by 2022. To help achieve those goals, the group is “committed to exercising our ownership rights to encourage increased representation of women on corporate boards and in executive management positions in Canada.” The letter encourages companies to take “prompt and considered action” to achieve these goals, through a variety of strategies. Most notably, the investors say they will assess the use of their voting rights when nomination committees or boards fall short of their expectations.

There are other similar initiatives afoot coming from large institutional investors (particularly pension funds) in the U.S. and Canada, as briefly outlined in Appendix A and B. These efforts are still relatively new, and the next few years will be a critical period to evaluate their effectiveness. Notably, ISS, one of the two most prominent proxy advisory services in North America, will generally recommend withhold votes for the chair of the nominating committee where the issuer has no gender diversity policy and where there are no female directors on the board. That recommendation came into effect for S&P/TSX firms in 2018 and for all TSX companies in 2019.

Box 1: A Made-In-California Approach To Board Diversity

In October 2018, California became the first state to require women on company boards of all sizes and industries. The measure requires at least one female director on the board of each California-based public corporation by the end of 2019, with the option to fine companies that fail to comply. Companies would need up to three female directors by the end of 2021, depending on the number of seats on their board. At the time of legislation one-fourth of publicly held corporations in California did not have any women on their board of directors. This concentration is predominantly within smaller firms in the state, where the policy will prove most effective.

Looking at the firms domiciled in California in the S&P500 very few have zero women on their boards, so the first phase of the law won’t move the dial when benchmarked to the outcomes of the S&P/TSX. However, once the 2021 requirements are in effect, all else equal, it would move the share of board female representation within California companies from 22.7% of board seats in our 2017 sample index to 31%, due to the sheer size of their representation and low starting point. If Canada doesn’t make parallel progress in the respective small-firm trouble spots, it will soon find itself once again behind the mark.

Vigilance against “twokenism” required

These shareholder initiatives are welcomed and C/E policy is proving effective in facilitating transparency, measurability and accountability. However, firms must guard against becoming complacent once they “hit a number” of two or three women on their boards. The goal should ultimately be to ensure a broad and equitable candidate selection.

Research5 on U.S. boards showed that when groups are scrutinized, decision makers strive to match the diversity observed in peer groups, conforming to social norms. In the context of U.S. boards, this showed that significantly more boards included exactly two women than would be predicted by chance – a phenomenon the authors coined “twokenism”.

Returning to Chart 2, the number of firms with one or two women on their board has remained fairly steady in recent years at slightly more than half. There has likely been churn among those in the category, but if this plurality of one or two women doesn’t decline going forward, it could indicate that complacency or a “twokenism” phenomenon has set in. A study by McKinsey6 showed that 45% of men think women are well represented in leadership when only one in ten senior leaders in their company is a women. In contrast, only 28% of women agree. Therefore, Directors may view their board as diverse with one or two women, and stop pushing the needle forward by truly broadening their searches or changing their approach to realizing the benefits of diversity.

In a recent report from Spencer Stuart, the share of new board appointments captured by women in its sample of 100 Canadian companies dropped from 40% in the early days of the C/E policy to 30% in 2018. This too should be watched as a potential early warning sign that a “hitting the number” effect might be taking hold. Should this become evident over time, further adjustments to the C/E policy may need to occur, like those recently taken by the state of California (Box 1).

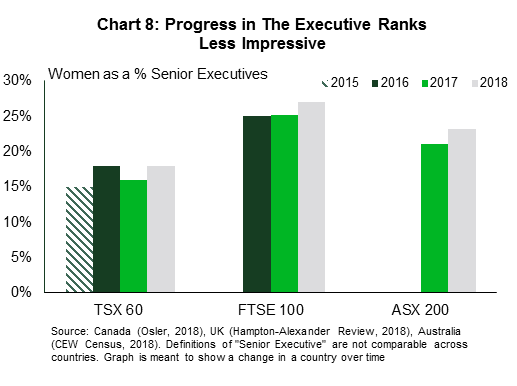

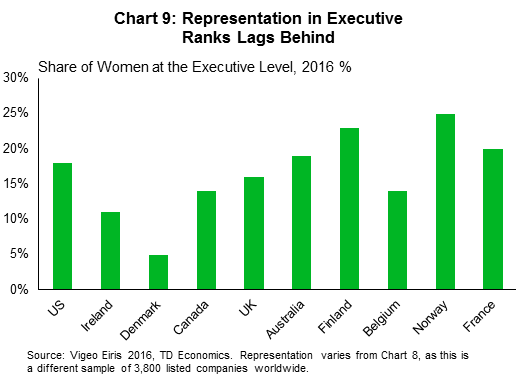

The other area requiring more exploration is the apparent ineffectiveness of C/E policy to materially influence the representation of women in senior executive ranks (Chart 8). Looking at Canada, Australia and the UK, there is a similar lack of progress in the executive ranks in all three countries, despite significant progress made at the board level. This does not seem to be a shortcoming of C/E policy alone, as the phenomenon also exists within countries that applied hard-quotas at the director level, like Norway (Chart 9). In fact, Norway offers a cautionary tale that more time may not be the cure to higher female executive representation. Norway has maintained a 40% quota policy at the board level for over a decade, giving it the longest history with a policy among our list of advanced countries. And yet, the executive ranks far lag their board quota equivalents and are not that different from other countries with much “younger” policies. Ultimately, across all countries, the lagging outcomes within the executive ranks may be a function of less public scrutiny relative to higher profile board positions. However, this is one area where more research would be welcomed, because even the definition of “executive” varies by firm and country, which makes measurability and comparability of results more difficult.

The Bottom Line

Since C/E policy came into effect, there’s no question that Canada’s corporate boardrooms have made noteworthy progress on gender diversity over a short period. Headway has been made across industries and firm sizes. Investors are now using the information to press for further change, precisely the benefit of a policy designed to harness market forces, rather than impose rigid standards. The next few years will be key for continued forward momentum and measured progress to ensure phenomenons like “twokenism” do not set in. Ultimately, to move the needle in corporate Canada as a whole, stronger headway needs to be made among smaller firms, and disproportionately within the resource sector.

The initiatives currently underway by investors should be given time to generate results before any adjustments to the current policy are considered. Given the progress seen by countries with similar policies that were implemented a few years earlier, it is likely that Canada’s gender representation will continue to improve. If in a few years it is evident that progress has reached a point of stasis, then it might be time to consider designing targeted policy at the trouble spots.

Appendix A

| Corporation | Shareholder Initatives: Canadian Examples | Year Implemented | ||||||||

| Glass Lewis | Generally will recommend voting against the nominating committee chair (and potentially other nominating committee members), if the board has no female members. May also recommend voting against where the board has not adopted a formal written gender diversity policy. However, it may refrain from recommending against directors of companies outside the S&P/TSX composite index if the board has provided a sufficient rationale for the lack of female board members (which rationale may include a timetable to address the lack of gender diversity and any notable restrictions in place regarding the board's composition). | 2019 | ||||||||

| Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) | Will vote against the chair of the board committee responsible for director nominations at its investee public companies if the board has no women directors. | 2018 | ||||||||

| Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) – Canada | For widely-held companies, will generally vote withhold for the Chair of the Nominating Committee or equivalent, where the company has not disclosed a formal written gender diversity policy, and there are zero female directors on the board of directors. | 2018 | ||||||||

| The gender diversity policy should include measurable goals and/or targets denoting a firm commitment to increasing board gender diversity within a reasonable period of time. Consideration will also be given to the board's disclosed approach to considering gender diversity in executive officer positions and stated goals or targets or programs and processes for advancing women in executive officer roles, and how the success of such programs and processes is monitored. | ||||||||||

| Policy came into effect in 2018 for S&P/TSX index companies, and will be in effect for all TSX-listed companies for 2019 proxy season | ||||||||||

| Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan | Updated its proxy voting guidelines to include a note on gender diversity, and a minimum of three women on a board | 2018 | ||||||||

Appendix B

| Corporation | Shareholder Initatives: U.S. Examples | Year Implemented | ||||||||

| CalPERS | Carefully monitor company's progress on gender diversity and enter into confidential engagements when necessary. In instances where companies fail to respond appropriately, will consider withholding votes from directors | Expanded engagement in 2017 | ||||||||

| Developed the Diverse Director DataSource, called "3D" in 2011. Facilitates finding untapped talent to serve as directors on corporate boards | ||||||||||

| Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) - US | For annual shareholder meetings occurring in 2019, will not issue adverse vote recommendations due to a lack of gender diversity on a company's board. However, effective February 1, 2020, adverse voting recommendations may be issued against nominating chairs at companies in the Russell 3000 or S&P 1500 indices with no women directors on boards | Updated 2018 | ||||||||

| Under updated policy, the absence of gender diversity may be mitigated by: | ||||||||||

| i) a firm commitment as disclosed in the company's proxy statement, to appoint at least one female director to the board in the near term | ||||||||||

| ii) the presence of a female director on the board at the preceding annual meeting | ||||||||||

| iii) other applicable relevant factors | ||||||||||

| Ability to explain and excuse lack of gender diversity temporarily should be limited to only "exceptional circumstances" | ||||||||||

| New York City Pension Fund | Launched "National Boardroom Accountability Project 2.0" an initiative that targets the boards of 151 US companies requesting they disclose their director skills matrix – disclosing each director's gender, race, and ethnicity as well as information regarding each director's skills, experience and attributes | 2017 | ||||||||

| BlackRock (US + Canada) |

In its proxy voting guidelines, boards are to be 'comprised of a diverse selection of individuals who bring their personal and professional experiences in order to create a constructive debate of competing views and opinions in the boardroom'. At least two women directors on every board | 2017 | ||||||||

| Seek to understand the company's philosophy, policies, and performance on diversity at the board level, and by extension, within senior management and the 'talent pipeline'. | ||||||||||

| Will recommend a withhold vote for the chair of the nominating committee (or chair) where the company has not disclosed a formal written gender diversity policy and there are no female directors on the board | ||||||||||

End Notes

- https://naisjohtajat.fi/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2016/05/eng-keskuskauppakamarin-naisjohtajaselvitys-2017.pdf

- https://www.issgovernance.com/file/publications/us-board-diversity-study.pdf?elqTrackId=011970cf767b4a1f8d518ad530d43a5a&elq=2a16fb283c9641bb834083fc56159ed7&elqaid=1083&elqat=1&elqCampaignId

- https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/the-tipping-point-women-on/0538249725

- https://30percentclub.org/assets/uploads/Canada/PDFs/30_percent_Club_Canadian_Investor_Statement_FINAL_Sept_5_.pdf Included 16 large Canadian asset management firms managing a combined total of $2.1 trillion in net assets.

- Edward H. Chang, Katherine L. Milkman, Dolly Chugh and Modupe Akinola (February 2019). “ Diversity Thresholds: How Social Norms, Visibility, and Scrutiny Relate to Group Composition.” Academy of Management Journal VOL. 62, NO. 1

- McKinsey & Company “Women in the Workplace 2018”.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: