Highlights

- Canadian women have been leading the charge into entrepreneurship since the recession. Overall, self-employment has been fairly flat since 2009, but self-employment among women has grown.

- While Canadian women are increasingly opting to pursue an entrepreneurial path, it seems to take a different route than their male counterparts. The male and female-owned businesses have distinct characteristics, reflecting differing occupational choices and motivations for entering entrepreneurship.

- Still, women remain underrepresented among entrepreneurs, whether looking at the self-employed or owners of small and medium-sized enterprises. The recent upswing in women entering self-employment is a positive sign that women are overcoming many deeply rooted hurdles and venturing out on their own. .

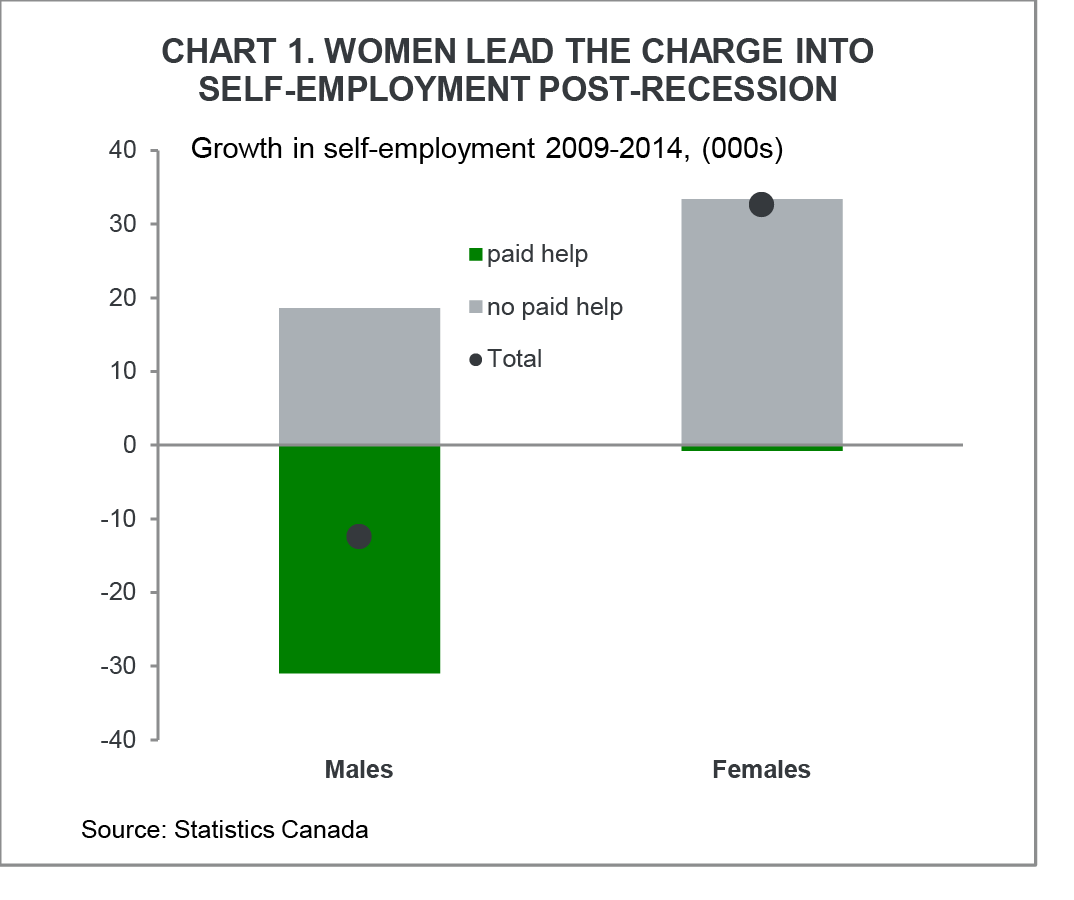

Canadian women have been leading the charge into entrepreneurship since the recession. Overall, the share of workers in self-employment has been fairly flat from 2009 to 2014, with growth in paid employment outpacing that of self-employment. However, self-employment among women has expanded, while having contracted among men (see Chart 1). While this data suggests Canadian women are increasingly opting to pursue an entrepreneurial path. That path often takes a different route than their male counterparts, resulting in distinct characteristics between male and female-owned businesses.

The characteristics of female entrepreneurs and their businesses are quite different from their male counterparts. The differences reflect the typical gender-industry breakdown, and motivations for entering self-employment. There is also evidence that factors which contribute to fewer women choosing entrepreneurship are present very early in women’s careers. In fact, despite the recent momentum into self-employment, women remain underrepresented among entrepreneurs, whether looking at the self-employed or owners of small and medium sized enterprises.

Portrait of women-owned businesses

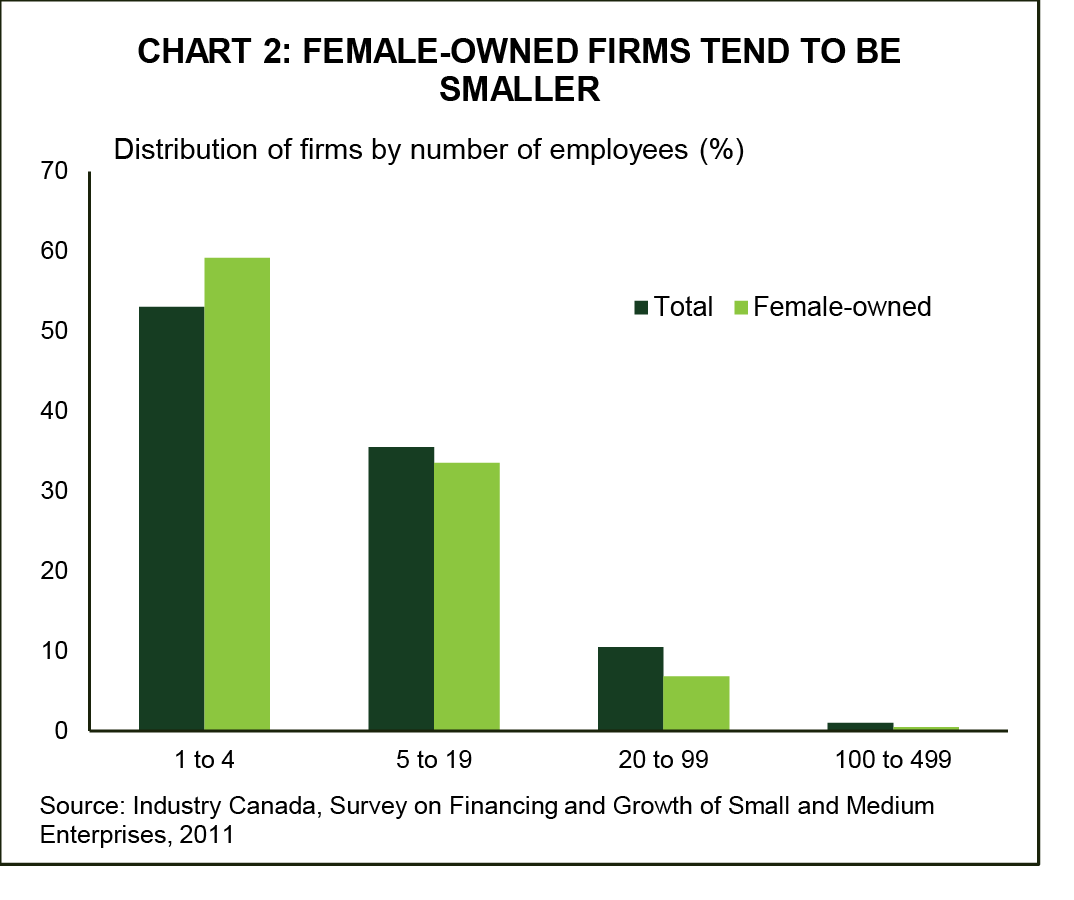

Industry Canada’s 2011 Survey on Financing of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) provides the most recent portrait of the characteristics of business owners. A small or medium sized industry is one with fewer than 500 employees, and between $30,000 and $500 million in annual revenues. The survey data came from responses of close to ten thousand businesses across Canada. There are several notable differences between businesses majority-owned by men, and those owned by women1. Probably the most notable is size. Women are more likely to own small businesses than medium-sized businesses (small 1-99 employees). Businesses are smaller whether measured by revenue or by number of employees. Women-owned firms are more likely to be in the 1-to-4 employee range (see Chart 2).

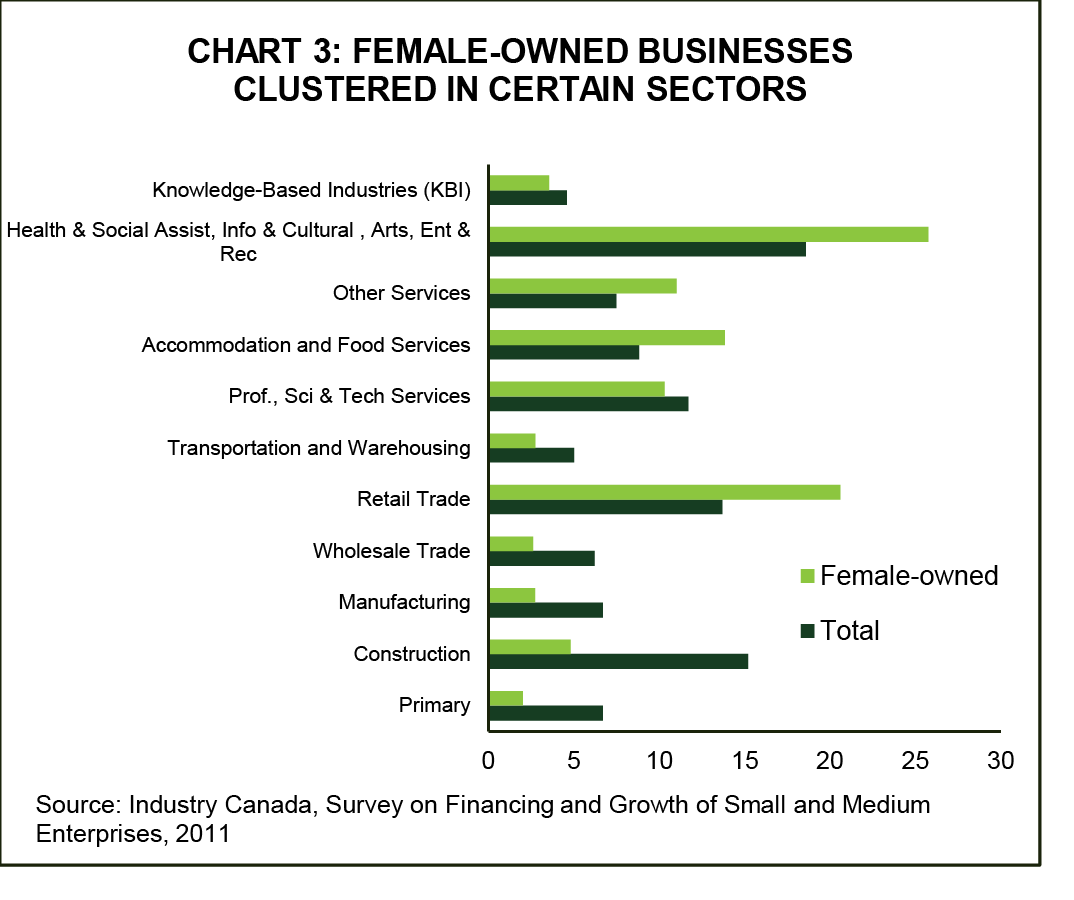

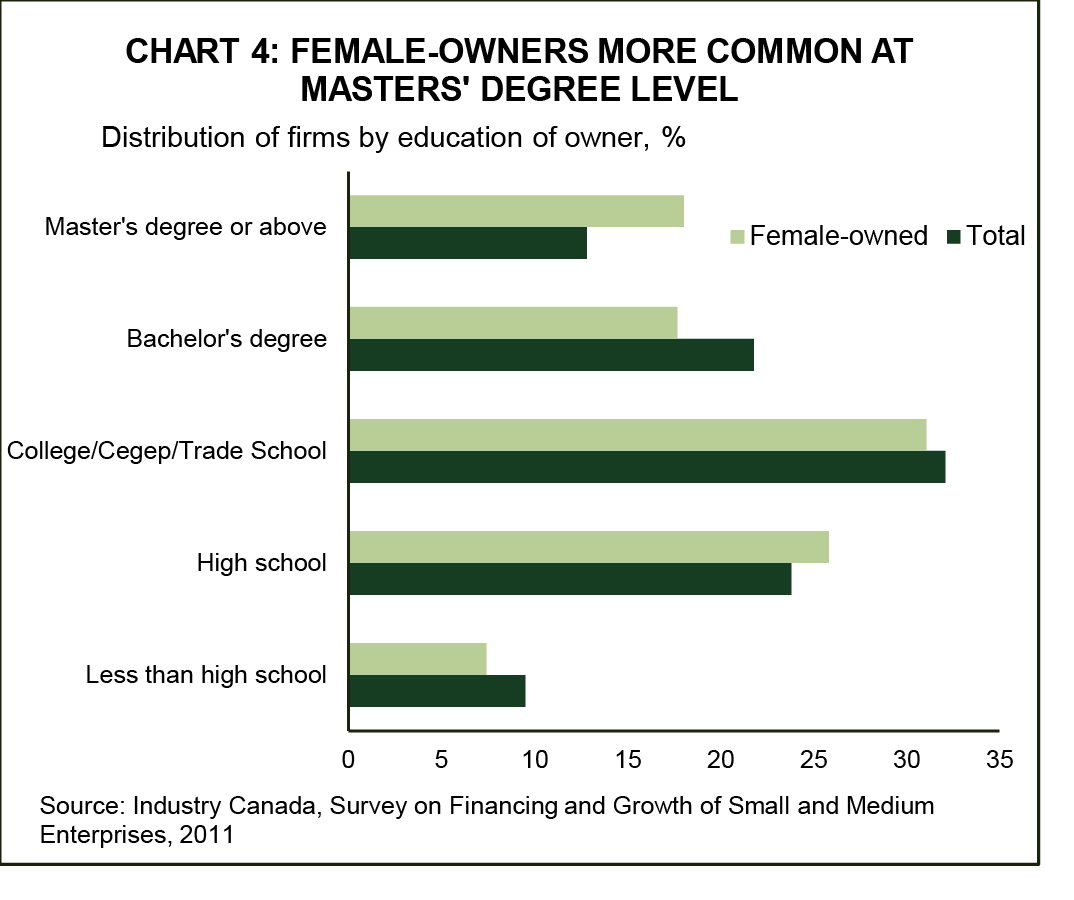

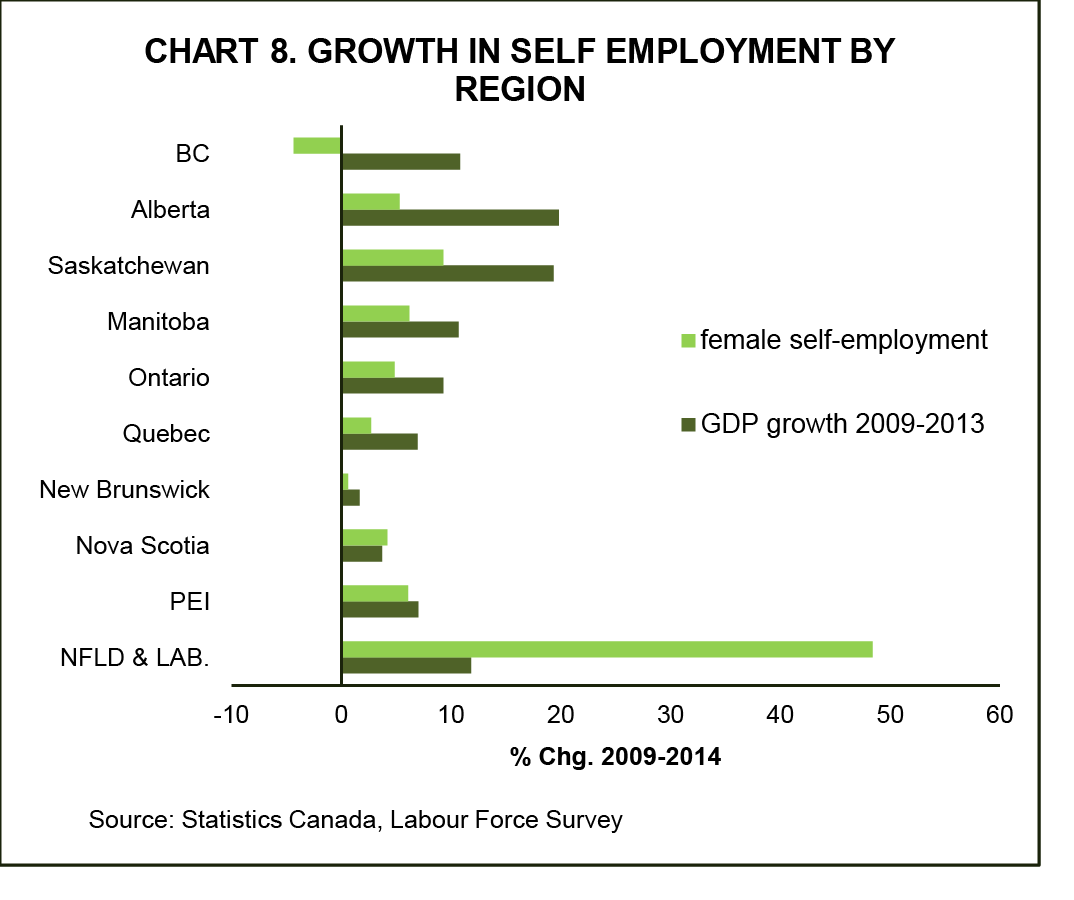

Women-owned businesses also predominate in traditionally female-centered industries (see Chart 3). Overall, 90% of women-owned SMEs are in the services sector, compared with 70% of those owned by men. Regionally, women-owned businesses were most common in Eastern Canada, with Atlantic Canada leading the way, and Quebec in second place. In terms of growth of women in self-employment from 2009 to 2014, Newfoundland and Labrador is far and away the leader with growth of 48%, with Saskatchewan (+9%), Manitoba (+ 6%), PEI (+6%), Alberta (+5%) and Ontario (+5%) all better than the national average growth of 3.3% since the recession. While the majority of female business owners have more than ten years of ownership or management experience, they have slightly less experience than their male counterparts. Interestingly, female SME owners are more likely to be highly educated (see Chart 4). They are also slightly more likely (25%) to be born outside of Canada than male owners (20%).

Despite being smaller, female-owned SMEs are slightly more likely than their male counterparts to have engaged in an innovation activity in the past three years. The most common type of innovation is a new or significantly improved good or service (a product innovation).

Women business owners seemed to be less likely to be pursuing other growth-enhancing strategies than men. Female owned SMEs are less likely to be engaged in exporting. Only about 5% of female-owned SME’s are exporters, compared to roughly 10% for all SMEs in the sample. This is perhaps not surprising given that women-owned SMEs are far more likely to be in the domestically-oriented services sector. Women-owned businesses are also slightly less likely to seek financing than male owned businesses. The main reason cited for not seeking financing, which was similar for men, is that they did not need it. Finally, in contrast to the self-employment data, the share of SME’s owned by women has not shifted much over the past decade. Only 16% of SME’s in the 2011 survey were majority-owned by women, the same share as in 2004. In fact, Industry Canada cited in a 2010 report2 that the gender distribution of SME ownership changed very little between 2001 and 2007.

There are several reasons why the two surveys tell a slightly different story on women’s entrepreneurship. For starters the surveys come from different samples: the self-employment data comes from the Labour Force Survey, which is a survey of 56,000 households across Canada, while Industry Canada’s data comes from a sample of 25 thousand private sector firms in the Business register. Moreover, the rise in self-employment among women since the recession is a fairly recent trend while the latest SME Data is from 2011. Another possibility is that the SME survey would miss micro enterprises with revenues less than $30K per year, or informal businesses that would perhaps not be included in the business register.

Motivations likely play a role determining characteristics

Entrepreneurship research has shown that motivations differ between male and female entrepreneurs, and this is likely shaping the portrait of women-owned businesses. Canadian research into the motivations of male and female entrepreneurs3 categorized them into three groups:

- classic: motivated by pull factors, such as independence, desire to be one’s own boss, earn more money, challenge or creativity (71% of men, 53% of women)

- forced: enter entrepreneurship due to lack of other alternatives (22% both men and women)

- work-family: entrepreneurship fulfills a desire towards greater work-life balance (25% of women, 7% of men)

The one quarter of women entrepreneurs who opted to run their own business out of a desire for greater work-family balance are likely to pursue less aggressive growth strategies. There is evidence that this is indeed the case.

There is also evidence that female entrepreneurs seem to set a maximum threshold size for their businesses, beyond which they are not interested in growing, and these thresholds are lower than their male counterparts4. Female entrepreneurs also tend to be more concerned about the risks associated with fast-paced growth, deliberately choosing to expand in a controlled and manageable manner. This implies that even many “classically” motivated women entrepreneurs pursue growth less aggressively than their male counterparts.

Not surprisingly the different gender motivations matter for income, with classic entrepreneurs having much higher income levels5. And, women who have become entrepreneurs for reasons of work-family balance may be less likely to pursue aggressive growth strategies that would require significant investments of time into the business. One example of a growth-limiting strategy by women entrepreneurs is a lower propensity to pursue exporting. Male-owned businesses have a significantly greater tendency to export, even after controlling for sector, firm and owner attributes6. Exporting enables businesses to access a much larger market for their products or services, enhancing the revenue growth potential, an opportunity that women entrepreneurs have so far been less likely to take advantage of.

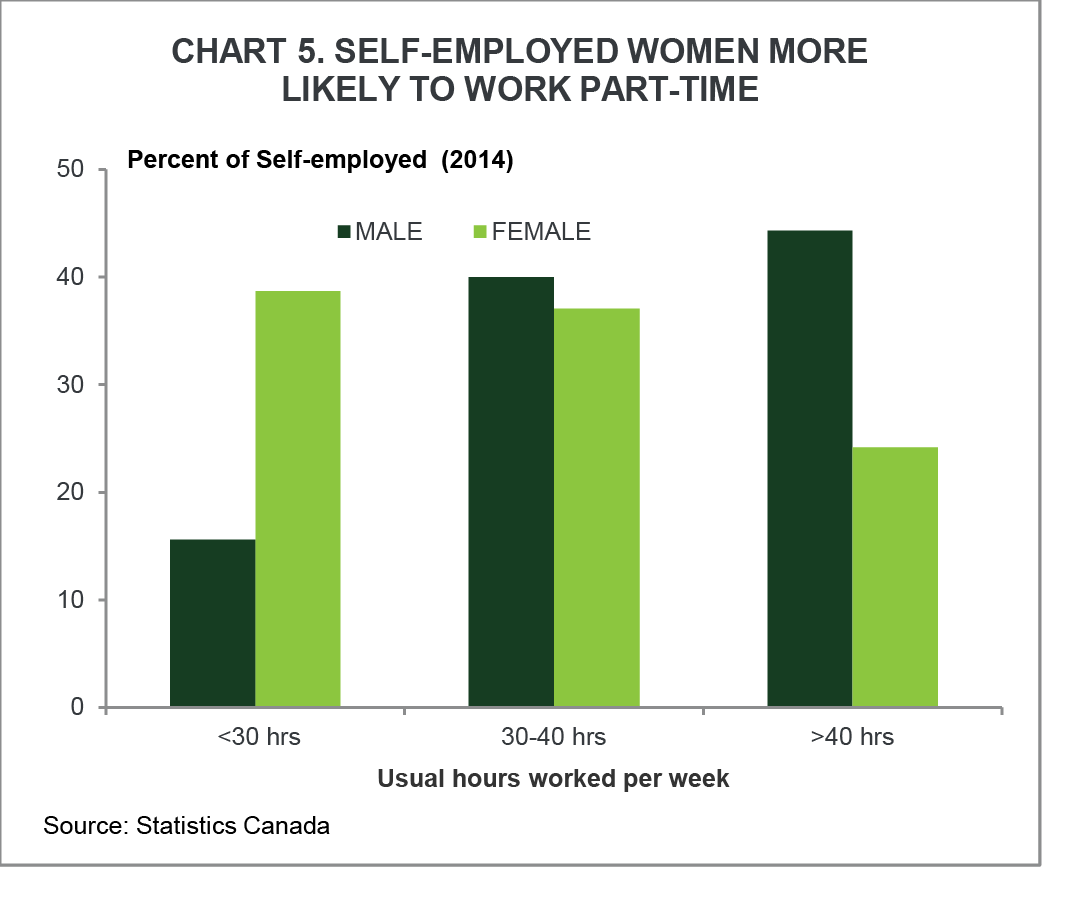

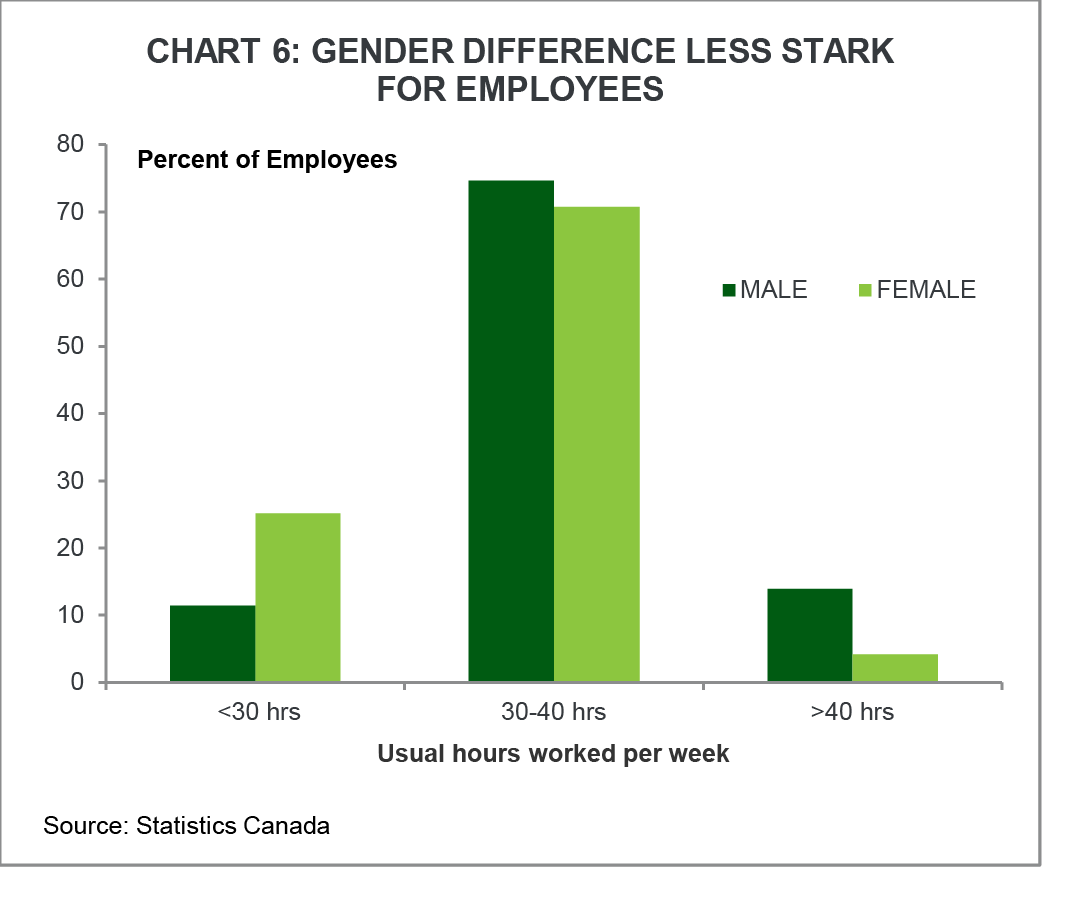

Another piece of evidence that points to women entrepreneurs being more likely to have entered self-employment to balance work and family responsibilities can be seen in the number of hours worked by self-employed men and women. Running your own business can entail long hours, and that is reflected in the average hours worked in a typical week by either self-employed women or men. Self-employed people are more likely to report working more than 40 hours in a usual work week than paid employees (see Charts 5 & 6).

The flip side is that self-employed people are also more likely to be working part-time (fewer than 30 hours per week). However, as Charts 5 and 6 show, this is much more common for self-employed women. Whereas about one quarter of female employees are working fewer than 30 hours per week, nearly 40% of self-employed women are. It is likely that this reflects a desire by many female entrepreneurs to balance work and family or community commitments. One piece of evidence that this is the case is that self-employed women spend more time volunteering. Self-employed women (35%) were more likely than men (21%) to volunteer on a regular basis7.

Motivations also influence decision to become an entrepreneur

While motivations can help explain the different characteristics of women entrepreneurs, they also influence the decision to become an entrepreneur in the first place. The price of greater independence and income potential in self-employment is greater risk, which is manifested through greater variability of earnings relative to waged employment. Study after study shows that men are more responsive to the expected (and potential) earnings differentials between wage and self-employment than females, whereas women are more risk averse8. That greater risk aversion influences women’s choices early on in their careers. A Canadian study9 which surveyed enrolment in undergraduate entrepreneurship courses (in various disciplines) found that female enrolment is far lower than for males.

A lower propensity toward entrepreneurship among women starts young. Research has shown that women exhibit less “entrepreneurial self-efficacy”, meaning the belief in one’s ability to successfully be an entrepreneur based on a personal assessment of one’s skills, and this gap emerges early – among young adults or even adolescents. A recent study of young university undergraduates in 2010-201110 showed that in part this sort of confidence gap is partly attributable to past entrepreneurial experiences and positive or negative feelings towards entrepreneurship. In the sample, male undergraduates were almost twice as likely as females to have already engaged in some form of entrepreneurial activity in the past. An entrepreneurial career was also less likely to generate feelings of excitement among the female students in the sample.

This line of research into early determinants of interest or feelings toward entrepreneurship shows that the bias away from entrepreneurship starts young. Moreover, it still exists among young women in North American who have arguably grown up in a period of relative equality of expectations and educational opportunity. Therefore, attempts to increase women’s participation in entrepreneurship would need to address these early held biases and beliefs.

Despite hurdles, more women going it alone

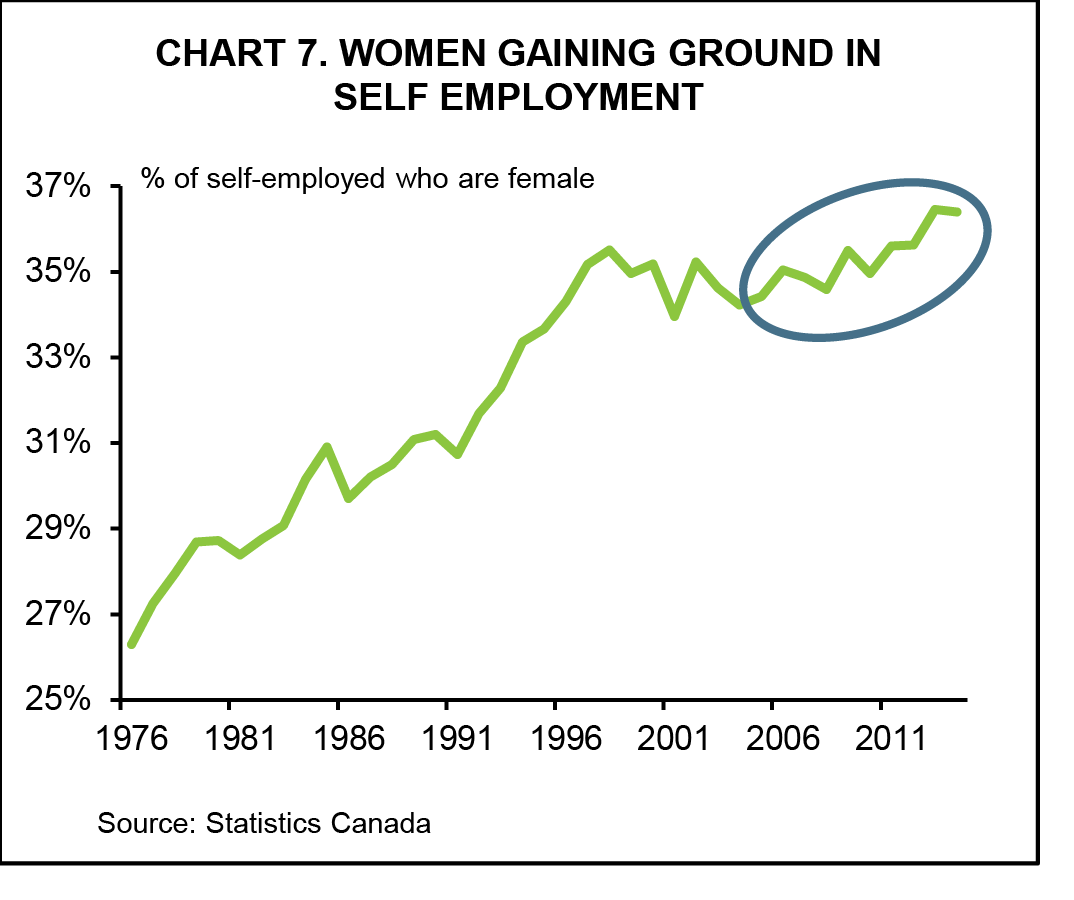

With all of these hurdles for women entrepreneurs, the increase in women entering self-employment is notable. Like the general uptrend of women entering the labour force, the share of women in self-employment rose dramatically from the late 1970s to the late 1990s and then stagnated for the next decade. But, with more women than men entering self-employment since the recession, the share of women among the self-employed has seen a nascent trend upwards (see Chart 7).

Another trend within self-employment is the growth in small, one-person operations. In the Labour Force Survey, Statistics Canada segments the self-employed into those who have “paid help” and those with “no paid help”. Since the recession, both men and women have seen growth in persons who are self-employed, but without paid help (see Chart 1). However, the growth in women branching out on their own has outpaced men.

There are a lot of possibilities for what might be driving this trend, but we can see which industries have seen the biggest gains in women’s self-employment. Not surprisingly, female dominated industries like educational services and health care and social assistance are leading the way. Growth in the professional, scientific and technical services industry is also quite strong. These would include many skilled professionals like lawyers, accountants, architects, engineers, specialized design services, advertising and public relations.

It is impossible to say with certainty from the data what is behind the increase in women branching out on their own, but there are a few potential factors. The likelihood of self-employment increases with age11, and tends to be more common in highly skilled services occupations12. Therefore, population aging could be playing a role. Female baby boomers are more highly educated and have had greater labour force attachment than previous generations and are therefore more highly skilled. The highly skilled occupations also have higher rates of self-employment (e.g. professional, scientific and technical services category). As female baby boomers move into their peak self-employment years, it would be expected to boost women’s self-employment overall – this is called a cohort replacement effect.

As discussed in the recent TD Economics report “Falling Female Labour Participation: A Concern”, employment has been weak recently in female-dominated industries, which could mean some of these women may have been forced into self-employment by losing their other job. If self-employment growth was a response to weak economic conditions, you might expect self-employment growth to be stronger in regions where economic growth has been weaker since the recession, but this does not appear to be the case, with growth darling Saskatchewan having a high growth rate in women’s self-employment, while weaker central Canada is lower (see Chart 8).

While there isn’t a definitive answer on the increase in female self-employment, it is an encouraging trend after a period of stagnation in women’s representation among entrepreneurs. And the future is looking bright. The research discussed above on “classically motivated” entrepreneurs also found that they were more likely to have a university degree than “work-family” entrepreneurs13. With women’s rising educational attainment, the available pool of future women entrepreneurs is very different from their mothers. When today’s business owners were young adults just starting out in 1990, only 43% of young women (25-34) had a postsecondary degree or diploma, slightly less than men. Today that number is 71%, ten percentage points higher than men. While increased educational attainment isn’t likely to be a perfect predictor of becoming an entrepreneur, it does deepen the talent pool to start tomorrow’s business ventures.

The Bottom line

While women make up nearly half the workforce, they are still much less likely than men to be entrepreneurs. Some factors like greater risk aversion and occupational choice, which help shape the gender entrepreneurship gap, are likely to be slow to change. However, the recent growth of women entering self-employment since the recession is a positive sign that women are overcoming many deeply rooted hurdles and venturing out on their own. The future is also looking bright as women’s increased educational attainment has significantly deepened the talent pool available to start tomorrow’s business ventures.

End Notes

- 1Women-owned businesses refer to those majority owned by women (>50%), consistent with previous Industry Canada analysis.

- Jung, Owen, “Small Business Financing Profiles, Women Entrepreneurs” Small Business and Industry Branch, Industry Canada, October 2010

- Karen D. Hughes, “Exploring Motivation and Success Among Canadian Women Entrepreneurs”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 19(2), 2006.

- Cliff, J.E., “Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size”. Journal of Business Venturing, 13: 523-542, 1998.

- Karen D. Hughes, “Exploring Motivation and Success Among Canadian Women Entrepreneurs”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 19(2), 2006.

- Orser, B., Spence, M., Riding, A. and Carrington, C. A., “Gender and Export Propensity,” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34: 933–957, 2010.

- Statistics Canada (2013) “Social Participation of Full-Time Workers”. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-004-m/75-004-m2013002-eng.pdf

- Le Maire, Daniel and Schjerning, Bertel, “Earnings, Uncertainty and the Self-Employment Choice” Discussion Paper, Centre for Economic and Business Research, April 2007.

- Menzies, Teresa V and Tatroff, Heather, “The Propensity of Male Vs. Female Students to Take Courses and Degree Concentrations in Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 19, Issue 2, p. 203-218, 2006.

- Dempsey D and Jennings J (2014). “Gender and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: a learning perspective”. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 6 No.1, 2014.

- http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/061.nsf/eng/rd00246.html

- http://business.financialpost.com/2013/08/21/the-age-of-entrepreneurship-why-self-employment-may-be-in-your-future/?__lsa=d7c4-3611

- Karen D. Hughes, “Exploring Motivation and Success Among Canadian Women Entrepreneurs”, Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 19(2), 2006.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: