Highlights

- The labour force participation rate among women with children under the age of 6 has skyrocketed since the pandemic. It has risen by 4 percentage points since 2020, equating to roughly 111,000 additional working women, a sharp acceleration from the 1.7 percentage point increase posted in the previous 3 years.

- Two factors have been at play. One is the rise of workplace flexibility, which has been a game changer in better aligning work and family responsibilities. The second is the longer-term rise in labour force attachment among young mothers, which is now being amplified by improved access to affordable childcare.

- Industries that offered flexible work arrangements during the pandemic, such as finance & insurance, saw sharp increases in employment for mothers with young children, while those industries that couldn't, such as food & accommodation, saw marked declines.

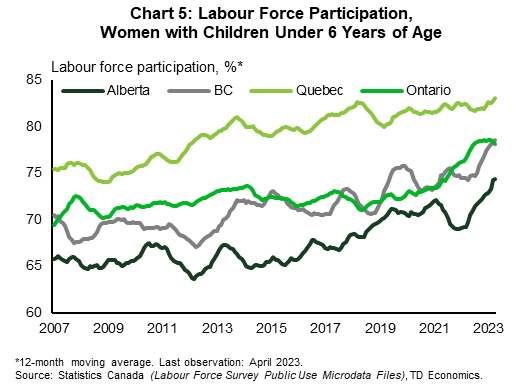

- Childcare affordability measures implemented by provinces were also visible in the data, with Quebec naturally leading the way since the early-2000s. However, more recent measures in both BC and Alberta have led to rising participation rates among mothers within the last few years.

- Remote work has since given way to hybrid arrangements, placing more emphasis on sustaining accessible and affordable childcare. We estimate that commitments to create new childcare spaces will fall short by 243,000-315,000 spaces to sustain the current up-trend in participation rates.

Introduction

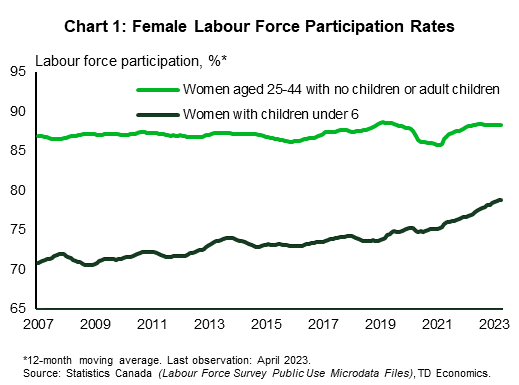

Women with young children have been joining the labour market in droves. Since the summer of 2020, the participation rate among those with children under the age of six has surged by 4 percentage points, a pace that’s more than double the prior three years. This bucks the overall trend in the participation rate, particularly among prime working-age women who either have no children or whose children are adults (Chart 1). Two main factors have been at play for these mothers: the rise of remote and flexible work options and improvements in childcare affordability in some provinces.

Whether this momentum can be sustained is uncertain. Remote work is beginning to give way to hybrid arrangements, which puts the onus on more affordable childcare to maintain the trajectory of the participation rate, particularly as a growing share of the baby boomers retire from the labour force. All provinces have now signed agreements with the federal government in its Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework to provide $10 per day childcare, on average. However, the bigger issue is that once the costs meet that benchmark, will there be sufficient childcare spaces to absorb the influx in demand? It is here where uncertainty lingers. Existing commitments for additional childcare spaces for every province reveal a likely shortage of spaces.

Workplace flexibility and childcare affordability helping families with young children

Entry into the workforce by mothers with young children had been on the rise for some time, but the crawling pace was given a bolt of energy during the pandemic. As shown in Chart 1, the gap between this group of women and others significantly narrowed by 3.1 percentage points in the span of just three years.

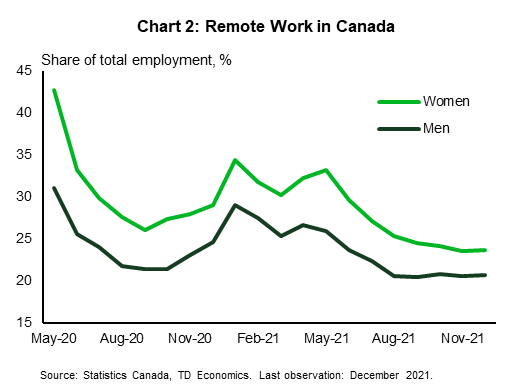

Workplace flexibility since the pandemic has had a clear influence on this trend. When Statistics Canada began collecting data on remote work back in May 2020, the share of women working exclusively from home had hit a peak of 42.7%. That share fell as more industries normalized but remained elevated even through the end of 2021 (Chart 2). By December of that year, the proportion of women working from home fell, but remained relatively high at 23.7%.

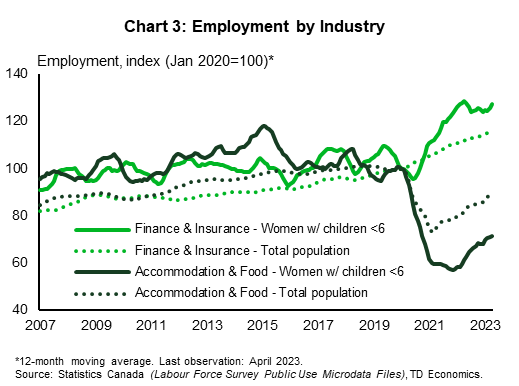

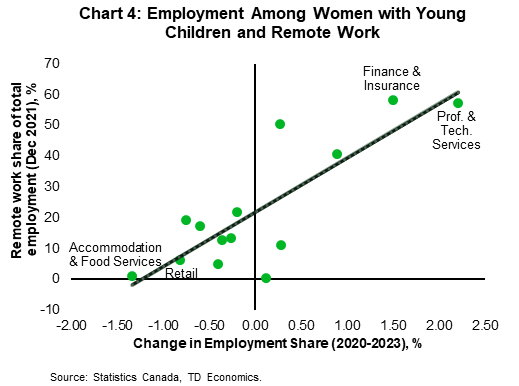

This effect is clear when looking at industries where remote work was most and least common, namely finance & insurance and accommodation & food services, respectively. Employment among mothers with young children in the former saw a noteworthy structural increase after the pandemic, with employment gains far exceeding the broader population. In contrast, employment in accommodation & food services went in the other direction, falling more for women with young children and being slower to recover (Chart 3). In fact, this pattern is consistent across industries. As shown in Chart 4, there is a direct correlation with the change in the employment share since 2020 among women with young children and the rates of remote work that occurs within an industry (Chart 4).

This incidentally puts office work at a significant competitive advantage to other industries in attracting this part of the labour force. Many industries that work primarily onsite, such as construction, manufacturing, or where office work is in the minority, such as retail, provide less appeal to working mothers with young children who show a self-selection signal towards industries that offer greater flexibility.

The other factor contributing to rising participation among this demographic group has been the impact of provincial policies aimed at lowering childcare costs. The participation rate among mothers with young children had already been on a steady upward trajectory prior to the pandemic within provinces that were already implementing policies to provide more financially accessible daycare. Most well-known among the initiatives is Quebec’s subsidized childcare program, introduced in 1997 at $5/day and subsequently expanded (currently at $8.85 per day as of 2023). However, both Alberta and BC followed suit more recently and were also starting to see more labour market engagement. Alberta launched their Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) initiative in 20171 and created 122 ELCC centres, 7,300 childcare spaces with capped fees at a maximum of $25 per day. Meanwhile, the Child Care B.C. plan2 from 2018 lowered fees at licensed facilities, created upwards of 12,700 childcare spaces with maximum fees of $10 per day, and provided an early childhood educator (ECE) wage enhancement, among other improvements.

The impact of these individual policies comes through in the dynamics of provincial participation rates for women with young children (Chart 5). Quebec’s participation rate rose consistently from 2007 through to 2018 but stayed steady from there onwards. In the three other largest provinces, the rate largely stagnated over that same timeframe until policies were enacted. For instance, a noticeable uptick in Alberta’s participation rate emerged in 2017 and in BC after 2018. Meanwhile, in Ontario, where there had been no policies to reduce childcare costs, the participation rate barely moved. That all changed once flexible work arrangements took hold in 2020 within all provinces except Quebec. Quebec was the exception perhaps because it was already at the forefront of affordable childcare policies for 28 years, making flexible work options a lesser factor after already attracting the lion’s share of mothers who wished to work.

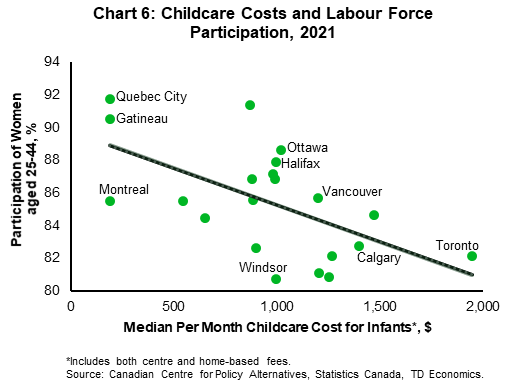

In short, childcare is an area where policy can and does have a significant impact. Chart 6 shows the clear relationship between childcare costs and participation rates, with cities that have lower costs tending to have higher labour force attachment among mothers. In Toronto, where median childcare costs for infants reached a staggering $1,948 per month and where centre-based care hit $2,029 per month in 2021, the participation rate for mothers with young children was lower than almost every other major urban centre in the country, with the exception of only Kitchener, Edmonton, and Windsor. Most telling of the impact affordable childcare has is in the participation rate gap between Ottawa and Gatineau. Separated by a mere nine kilometers, differences in daycare funding costs contributed to a sizeable 3.1 percentage point gap in participation rates in 2019. By 2021, that gap had swiftly narrowed to 1.9 percentage points as flexible work arrangements took hold.

The motherhood penalty and labour force scarring

The benefits of timely, affordable access to childcare cannot be understated. A recent analysis on the gender wage gap by Statistics Canada suggests that the gap closed by 6 percentage points from 19.6% in 1997 to 13.4% by 2017, largely due to newer generations of women being better educated than men and succeeding in higher-paid occupations than in the past3. However, the author notes that despite a smaller gap, a larger 70% share of it remains unexplained by human capital or occupational characteristics and attributes it partly to the motherhood penalty.

Policies that facilitate mothers returning to work following parental leave reduce the long-term wage penalty and labour market scarring that occurs. Data suggest that mothers whose work interruptions last longer than three years face close to a 30% wage penalty relative to similar-aged women without children by age 40. A one-to-three year disruption before the age of 33, however, resulted in nearly no wage gap between the two groups after that age of 334. This suggests that there are ways of stemming the impact of skills atrophy and other impacts by acting early. Previous TD Economics research5 also cited factors such as returning to the same employer, the frequency and duration of disruptions, and the timing of disruptions having various effects on the motherhood penalty.

Hybrid work emphasizes affordable childcare

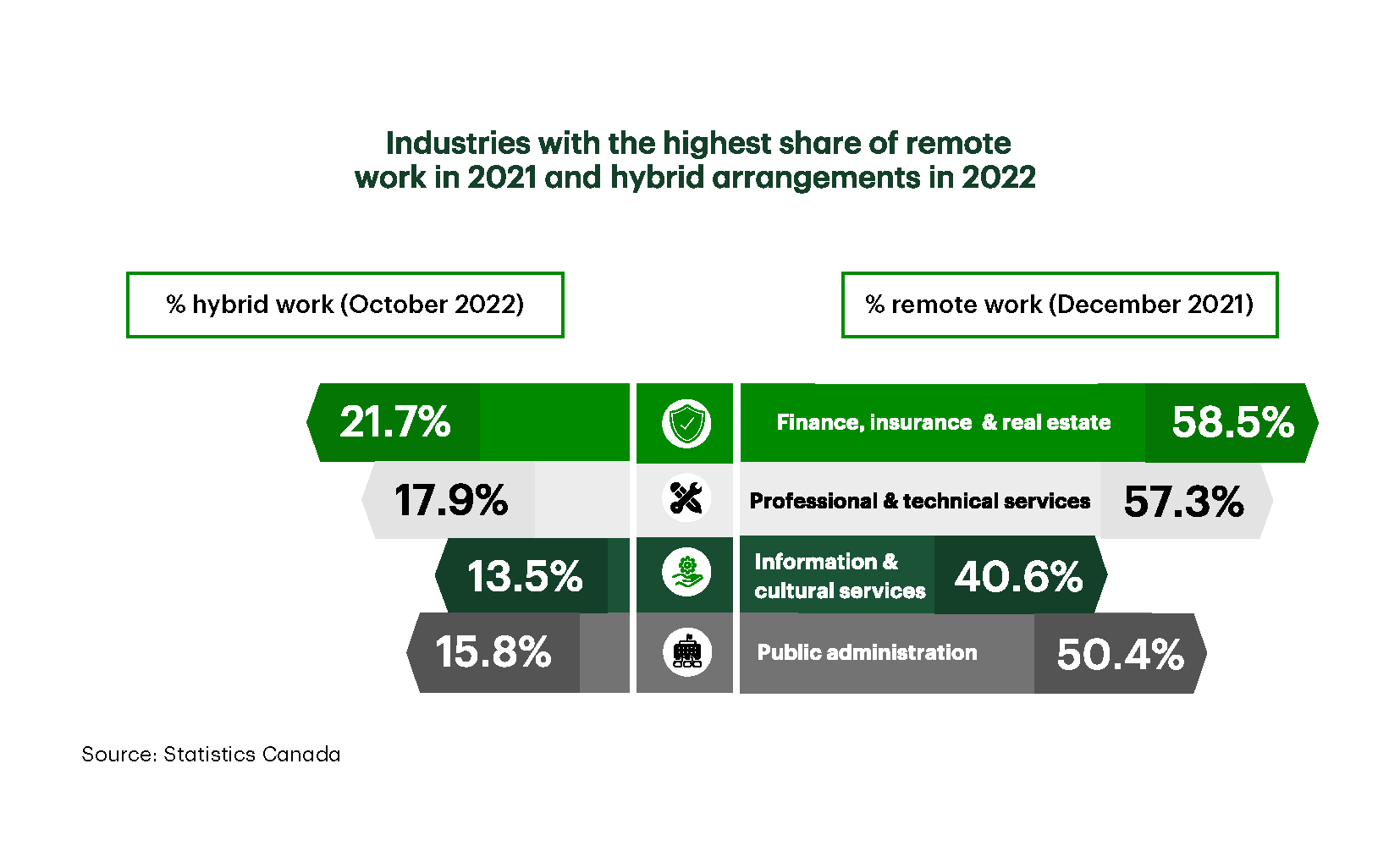

As the influence of the pandemic fades, firms are increasingly gravitating away from fully remote work arrangements in favour of hybrid location models. By October of last year, Statistics Canada estimated that the share of workers in remote arrangements had fallen further to 15.8%, while 9.0% were reported working from both home and other locations6. Notably, industries with the highest share of remote work in 2021, were also the likeliest to report hybrid arrangements in 2022, including finance, insurance & real estate (21.7%), professional & technical services (17.9%), information & cultural services (13.5%), and public administration (15.8%).

The fact that the shift towards hybrid work has not driven a reversal in participation rates among mothers with young children suggests that the issue is less about being fully remote and more about having flexibility in one’s work schedule. However, there can be no doubt that an increase in physical presence in offices and worksites enhances the need for affordable childcare. More recent evidence points to further movement towards hybrid work7, making the timing of affordable childcare ideal to intersect this changing landscape.

All provinces and territories have committed to reducing daily childcare fees to $10 per day as part of the federal government’s Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework, which will dole out $27.2 billion to provinces through 2026. Since delivery of that funding has begun, several provinces and territories have reduced fees to the point where they’ve already met that goal, including Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Newfoundland & Labrador, Nunavut, and the Yukon Territories. The remaining provinces and territories successfully reduced fees by 50% before the end of 2022 on route to $10 per day by 20268.

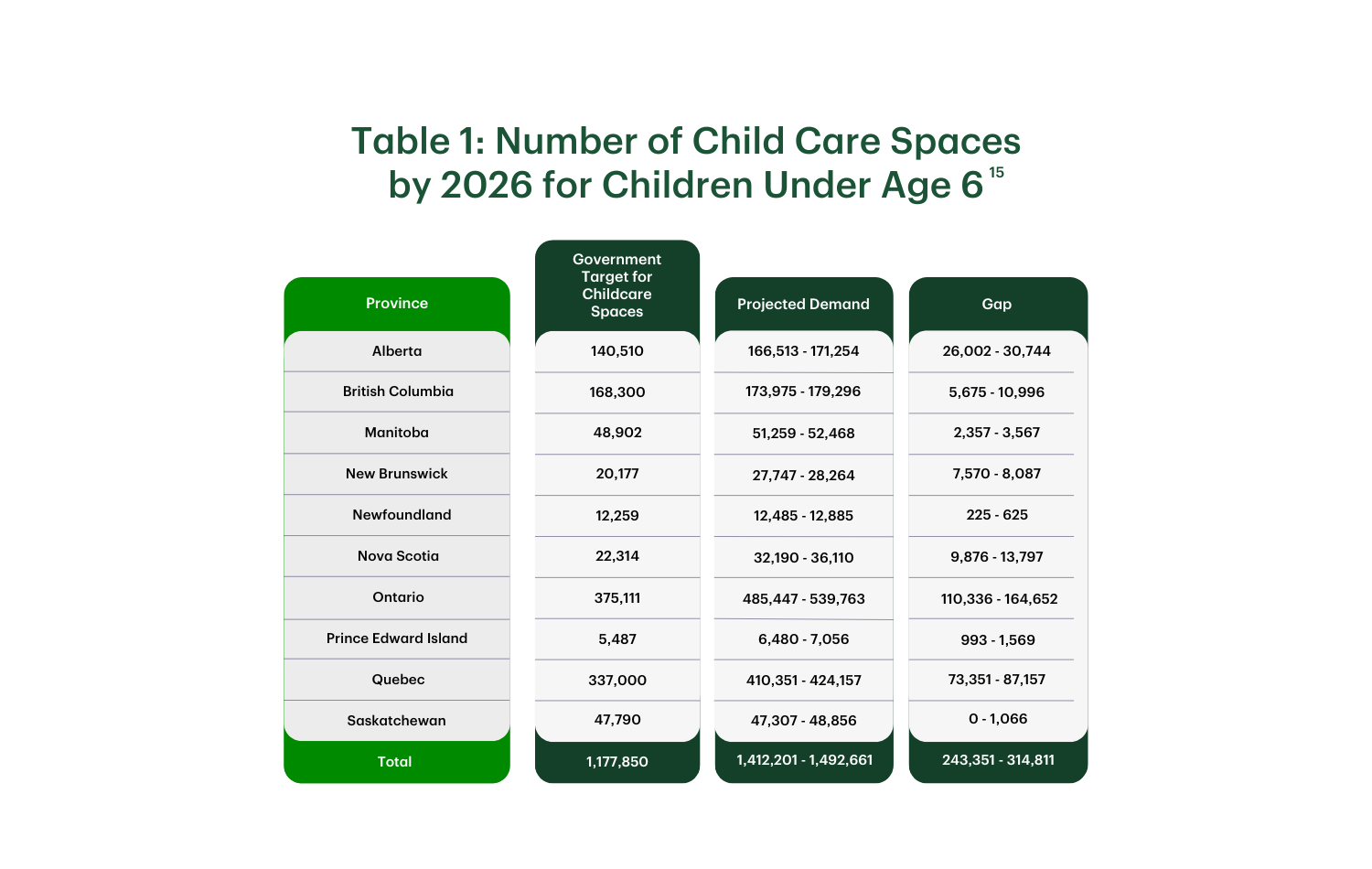

The challenge, however, is that there will be increased demand for childcare spaces that will likely far exceed provincial commitments as part of the funding arrangements. Based on the number of spaces each government has so far committed to creating, we estimate a gap of between 243,000 - 315,000 spaces for children under the age of six by 2026 (Table 1).

This gap is not a negative outcome, per se, because it is clearcut evidence that governments are delivering on something with a tremendous amount of unmet demand. And meeting that demand is not simply a question of finding physical spaces and reducing fees, but rather in attracting and training early childhood educators (ECEs). Provincial regulations set staff-to-child ratios and maximum group sizes, typically ranging from 1-to-3 to 1-to-10 for pre-kindergarten-aged children, with some ratio of those workers needing to be registered ECEs9,10. In Ontario, for example, infants younger than 18 months have a ratio of workers to children of 3-to-10, with maximum group sizes of just 10 and one of those 3 workers must be a registered ECE or equivalent. For children between 3 and 6 years, the ratio is 1-to-8 and maximum group sizes of 24, but two of the three workers must be ECEs or equivalent.

For the nationwide 315,000 space gap estimate above, we estimate that it would correspond with 32,000-105,000 additional childcare workers, of which roughly half need to be registered ECEs. This is a tremendous challenge to both train and retain workers, particularly as wage pressures are balanced against fiscal coffers. Provinces provide wage top-ups to ECEs to help with retention, with those top-ups increasing from more federal funding. For example, Ontario introduced a wage floor of $18/hour in 2022, rising to $21/per hour by 2025, with an additional $1/hour subsidy for RECE childcare program staff with recent discussions suggesting that those top-ups could increase further11. Meanwhile, in Alberta12, wages are expected to range from $19.43/hour to $28.50/hour this year depending on the level of certification for ECEs, which includes a wage subsidy of between $2.14/hour to $6.62/hour.

Still, in terms of how federal and provincial funding is split, support for ECEs is secondary to fee rebates to parents. Of the additional $2.3 billion expected to be spent in fiscal 2023 in Ontario on improving access and affordability, 70% is going to direct transfers to parents in fee rebates. This leaves just shy of $700 million for creating new childcare spaces and providing wage enhancements and training support for workers. The province already estimates that federal funding will fall short of net new spending by roughly $750 million by 2026, meaning taxpayers will be on the hook with the gradual uptick in costs over time.

Equitable geographical access, childcare deserts, and fiscal sustainability

As a result, there are still significant open questions about how governments will deliver on their childcare promises, both now and in the future. First, even beyond the simple math of how many childcare spaces will be needed to meet the demand of new mothers, the locations of those spaces will need to be distributed in a way to avoid so-called “childcare deserts”. Coined by researchers in the U.S.13, the term refers to the concentration of support for licensed childcare spaces in areas that already have sufficient workers and centres. However, this often ignores regions outside of major metropolitan centres. Data show that indeed smaller communities tend to have fewer childcare spaces than big cities where access is generally better14, with 48% of children living in regions with more than 3 children for every licensed childcare space.

Ensuring equitable access across the country could potentially push costs beyond what funding is available today, raising serious questions about the ongoing fiscal sustainability of this system. There is currently no line of sight on how the fee schedule and funding arrangement will evolve over time. Is the per day cost of daycare tied to $10 in perpetuity? Or will it grow modestly over time as in Quebec? Regardless, the subsidy is likely to lead to a falling real cost of childcare beyond 2026, putting additional financial pressure on governments to continuously fund a growing and increasingly expensive system. Policymakers may need to consider means-testing funding or fee rebates down the line to ensure that support is targeted at those most vulnerable to balance equity with fiscal sustainability. Conversely, the per day cost may need to be indexed to an anchor, such as the median income, the minimum wage, or the market-basket measure of the cost of living, in order to provide some surety that cost of childcare does not grow out of control.

Conclusion

The pandemic has been a transformative force in the labour market for more reasons than one. The rise of remote and more flexible work arrangements has accelerated the entry of more mothers into the workforce, which is now being further amplified by access to affordable childcare. This highlights the importance of getting it right by ensuring the supply of daycare spaces adapts to the needs of the workforce, otherwise it will remain a barrier to entry for some.

Attracting and retaining ECEs has to be front and centre in policy, with governments and post-secondary education institutions ensuring sufficient capacity to train workers, as well as the appropriate identification and expansion of physical locations. To not do so at a sufficient scale means that governments will have succeeded in reducing fees largely for parents that already had access, while those previously left out see lesser change to their situation. That’s the space between us.

End Notes

- https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories/alberta-2017.html

- https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/child-care/9107_childcarebc_factsheet.pdf

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-20-0002/452000022019001-eng.htm

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-001-x/2009103/article/10823-eng.htm

- economics.td.com/domains/economics.td.com/documents/reports/PDF%20modification/Career_Interupted.pdf

- https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221104/dq2eng.htm

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-remote-work-revolution-fail/

- https://www.budget.canada.ca/2023/report-rapport/chap1-en.html

- https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/7416669c-bc2e-4598-8f9c-0b25dbfc9e4f/resource/9f1c3a1d-31ad-4c05-929f-042033d23381/download/cs-changes-in-child-care-coming-into-effect-february-1-2021.pdf

- https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories/ontario-canada-wide-2021.html

- https://globalnews.ca/news/9754445/ontario-to-boost-ece-ewages/

- https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-child-care-grant-funding-program.aspx

- https://www.americanprogress.org/series/child-care-deserts/

- https://policyalternatives.ca/childcaredeserts

- Government targets are estimated from existing licensed spaces plus new provincial targets by 2026. Projected demand is estimated from population projections from Statistics Canada and child care use data from the Survey on Early learning and Child Care Arrangements public use microdata files. Source: Statistics Canada, Provincial and Federal websites, TD Economics.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: