A "Real" Perspective on the Monetary Policy Tightening Cycle and Borrowing Decisions

James Marple, AVP | 416-982-2557

Faisal Faisal, CFA, Manager | 416-983-1738

Date Published: July 5, 2022

- Category:

- Canada

Highlights

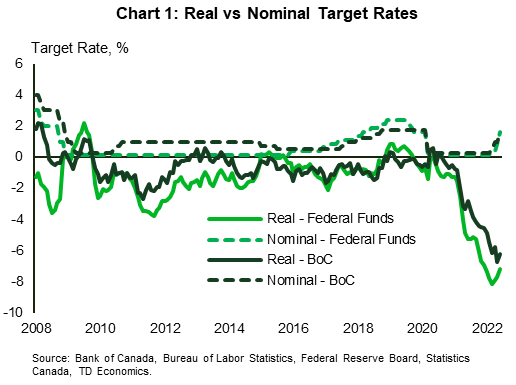

- Central banks are raising interest rates but from a point well below the current rate of inflation. As a result, real policy rates are still deeply negative.

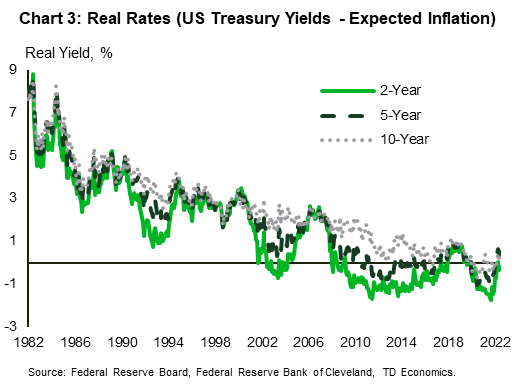

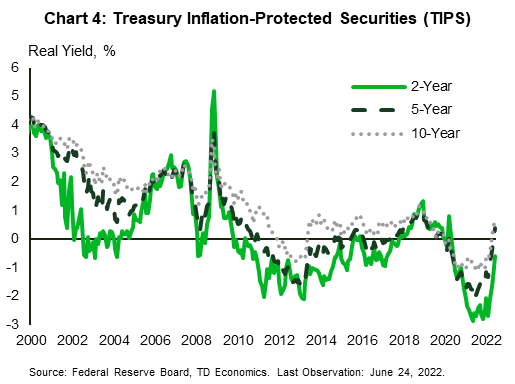

- Anticipation of higher policy rates has helped push up longer-term interest rates, but much of the increase is attributable to higher expectations for inflation. Real interest rates – or nominal rates adjusted for expected inflation – have only recently turned positive.

- Real rates are what matters for investment and saving decisions. For fixed-rate borrowers, high inflation lowers the value of the future stream of interest payments, while for savers, it eats into nominal returns.

- Consider the case of a Canadian taking out a five-year fixed-rate mortgage at the current posted rate of 4.6%. Should inflation average one percentage point higher (annually) than anticipated, a borrower on the average priced home will save close to $6,500, equivalent to reducing their annual mortgage rate to 3.4%.

- The higher the expected rate of inflation moves relative to nominal borrowing costs, the more attractive borrowing today becomes. If inflation expectations continue to drift higher, central banks will have to go even further in order to bring it to heel.

Global inflation rates have increased substantially over the past year, driven by rising energy prices, supply chain constraints and rebounding demand. In May, consumer price inflation hit a 40-year high of 8.6% year-on-year (y/y) in the U.S. and 7.7% y/y in Canada. Inflation is expected to accelerate further in June, reaching 8.8% in the U.S. according to the median analyst estimate.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) and Federal Reserve (Fed) have responded to mounting inflationary pressures by signaling an aggressive tightening cycle. From 0.25% earlier this year, the federal funds target rate has risen to 1.75% and the Bank of Canada's overnight target rate to 1.5%. Central banks are expected to continue to raise rates at an aggressive pace, with rates expected to hit 3.25% in both countries by the end of this year.

Discussion of the monetary normalization process has focused to a large extent on these nominal policy rates. However, inflation reduces the real cost of borrowing (and the return on saving) for those able to negotiate their lending rates today. As inflation has moved well above its recent historical experience, the distinction between real and nominal interest rates has become more relevant.

The importance of inflation in driving economic outcomes can be illustrated by the case of a Canadian household taking out a five-year fixed-rate mortgage at the current posted rate of 4.6%. If average inflation comes in one percentage point higher than expected, it will save a borrower on the average priced home close to $6,500 in current dollars, equivalent to reducing their annual mortgage rate to roughly 3.4%.

The higher the expected rate of inflation moves relative to nominal borrowing costs, the more attractive borrowing today becomes. If inflation continues to surprise on the upside or expectations continue to drift higher, central banks will have to go even further in order to tighten financial conditions and bring it to heel.

Real policy rates are at historical lows, even after rate hikes

Up until recently, nominal policy rates had been stable at the zero lower bound. Central banks have started to raise policy rates, but at the same time inflation has increased. Subtracting headline inflation from current policy rates implies rates that are deeply negative.1 In real terms, the Bank of Canada's overnight rate hit a record low of -6.2% in June, while the real fed funds rate was -7.2%, up from a low of -8.2% in March, the lowest rate since 1974 (at that time inflation was 12%).2 This compares to a 50-year average of around +1% in both countries. Even with the recent uptick in nominal policy rates, real policy rates remain deep in negative territory (Chart 1).

There is a broad consensus that real interest rates need to increase significantly more to bring inflation down to central banks' 2% target. We expect both the Bank of Canada and the Federal Reserve to lift policy rates to 3.25% by the end of this year and remain there over the course of 2023. With inflation expected to slow over the next year, this will likely bring real policy rates into mildly positive territory.

Real bond yields provide a different perspective on the tightening cycle

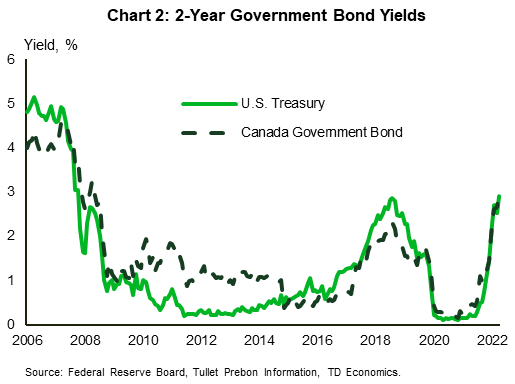

Central banks have direct control over very short-term rates (overnight), and while higher policy rates put immediate pressure on variable rates (and these have been a growing share of borrowers recently), the majority of debt, (including household, business, and government debt) is at longer-term fixed rates of interest.

Longer-term rates change with expectations for future central bank policy, as well as changes in expectations about inflation. As the Fed has lifted rates and telegraphed further rate hikes in the future, two-year government bonds yields have increased by roughly 270 bps since late August, reaching a high of 2.9% in the US and 3.1% in Canada (Chart 2).

In real terms, however, the increase has been less significant. Subtracting the two-year expected inflation rate (estimated by the Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) of Cleveland), results in a real yield close to zero over a two-year horizon. While this is above recent levels, it is low from a longer historical perspective (Chart 3).

The yield on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) tells a similar story. The TIPS yield, called a real yield because it represents the rate investors will accept once compensated for inflation. A two-year TIPS security provided a "return" of -0.6% last Friday, which is up from historical lows reached last year but also still well below its historical average. The 10-year shows a better story with yields getting closer the 1% mark, at 0.7%. (Chart 4)

There is yet other evidence that inflation expectations are moving higher and more broadly. The University of Michigan's monthly survey of consumer sentiment showed respondents expecting prices to advance 3.1% over the next five to 10 years, the most since 2008 and up from 3% in May. The Bank of Canada's Survey of Consumer Expectations released in early July showed that consumers' inflation expectations rose notably across all time horizons, with the two-years and five-years jumping to 5.0% y/y and 4.0% y/y, respectively.

What could higher than expected inflation mean for borrowers?

The higher the expected rate of inflation moves relative to nominal borrowing costs; the more attractive borrowing today becomes. If you are able to borrow money at a fixed rate, for example, and use it to make an investment that will provide something of value over time like buying a house or a car, higher inflation could make this even more attractive.

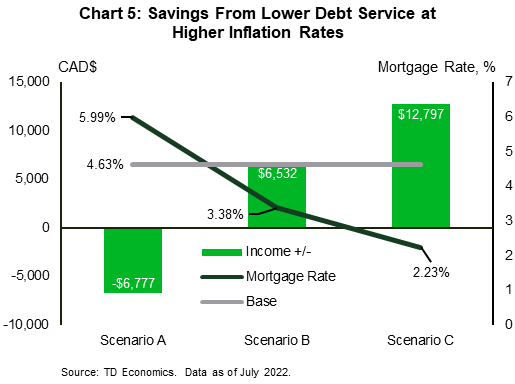

Consider the following scenarios based on the potential experience of a Canadian fixed-rate mortgage borrower under different inflationary outcomes:

- Inflation increases at our baseline forecast over the next five years

- Scenario A: inflation averages 1% less (annually)

- Scenario B: inflation averages 1% more (annually)

- Scenario C: inflation averages 2% more (annually).3

In the latter two scenarios – B and C – the amount of additional income a household can set aside if they enter into a 5-year fixed mortgage today is $6,532 and $12,797 CAD respectively, in today's value. These are savings that can be used to pay down remaining mortgage amount or – if fully anticipated – added to the down payment or used to alleviate household's other rising cost from food to energy.4

We go a step further and back out the resulting mortgage rate after factoring in these savings. Scenario-B would shave off (1.25 percentage points (pps)) and Scenario-C (2.4 pps) off the base rate of 4.6% (Chart 5).

The Bottom Line

Inflation poses a number of negative costs to the economy. If wages don't keep up, higher inflation pinches household purchasing power. Once wages catch up, it becomes more difficult to dislodge inflation and the need to constantly update prices adds costs to businesses, while greater volatility makes investment more uncertain and slows economic growth.

There is one silver lining to unanticipated inflation – it reduces real borrowing costs for fixed-rate borrowers. While the current posted mortgage rate is 4.6%, if average inflation comes in one percentage point higher than expected, it will save a borrower on the average priced home close to $6,500 in current dollars, equivalent to reducing their annual mortgage rate over the next five years to around 3.4%.The higher the expected rate of inflation moves relative to nominal borrowing costs, the more attractive borrowing today becomes.

End Notes

- As measured by the year-on-year percent change in the Headline Consumer Price Index.

- We estimate the June real rate by taking the Bloomberg consensus estimate for CPI inflation of 8.8% y/y, while in Canada we cautiously assume inflation remains at the same level from May at 7.7% y/y.

- In our scenario analysis, we consider an average Canadian household who enters into a five year fixed mortgage loan for 25 years at the current mortgage rate of 4.63%, with a 20% down payment or $175,000 CAD. An average home price of $875,000 CAD, making the total loan amount of $700,000 CAD and monthly payment $3,925 CAD. Based on the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CHMC) Gross Debt Service rate of 39%, the minimum Canadian average annual qualifying household income for this mortgage example is $134,000 CAD (the debt service rate includes property tax amount and utility costs).

- The savings are calculated by taking the difference of debt service costs relative to the base case. The higher the rate of overall inflation, the lower the fixed cost to service debt.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: