Policymakers Take Note: Population Growth is Easing in the Atlantic

Rishi Sondhi, Economist | 416-983-8806

Marc Ercolao, Economist | 416-983-0686

Date Published: July 18, 2024

- Category:

- Canada

- Provincial & Local Analysis

Highlights

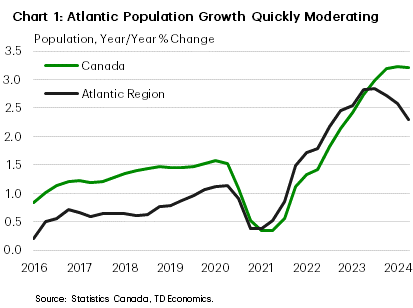

- Canada’s Atlantic region is experiencing a notable moderation in population growth. This contrasts with the nation at a whole, whose population growth is still humming at multi-decade highs.

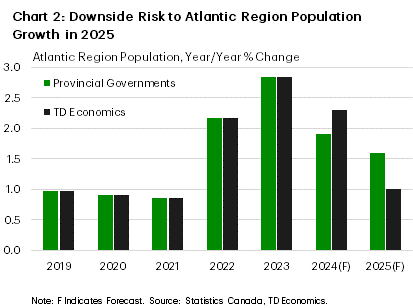

- Provincial governments’ lofty population projections, especially in 2025, are at risk of overshooting. This has the potential to put a damper on both household spending and overall economic growth, while also weighing on labour supply.

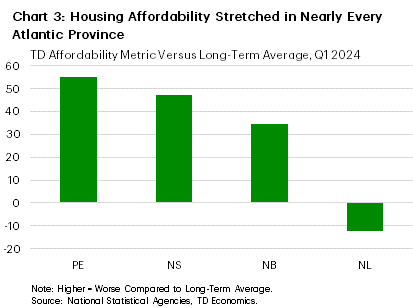

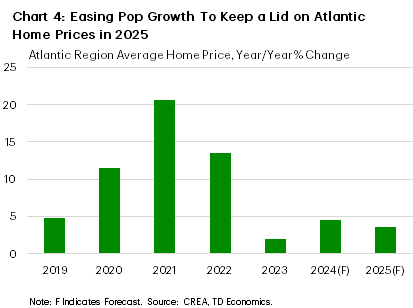

- Slower population growth would take some heat out of housing rental price growth and ease overall housing affordability concerns.

Recent immigrants have integrated comparatively well into Atlantic labour markets. - New federal immigration policy will work its way through the Atlantic region in various ways. However, no province is immune to the intended outcomes.

Population growth remains incredibly strong in the Atlantic Region. However, it is easing from sky-high rates, just as other parts of the country appear to be holding firm (Chart 1). We anticipate this trend towards slower population growth in the Atlantic will persist, marking a very important development for a region where economic growth has broadly benefitted more from recent population inflows. Consumer spending will be impacted, potentially flipping the script from the past few years when our internal data showed an outperformance compared to the rest of Canada. In fact, if population growth evolves more in line with what we expect versus what provincial governments are forecasting, then household spending growth across the region could be as much as 0.6 ppts lower next year than what’s implied by government projections. The construction sector will also be influenced, following a few years of very healthy gains. However, the impact could come with more of a lag as major projects are ongoing, and planned capital investments are robust in places like Nova Scotia, PEI, and New Brunswick.

Provincial policymakers should also take note, as slowing population growth implies downside risk to what are generally quite lofty growth projections for the year ahead (Chart 2). Indeed, in their latest budgets, the Atlantic provinces are projecting GDP growth of 3.3% next year (on a weighted average basis), twice as strong as our forecasts and over three times faster than the pace observed in 2022/2023, when the region’s population base really started expanding rapidly. Granted, part of this story reflects an assumed bounce back in Newfoundland and Labrador’s oil production, but the broader point still stands.

Housing Market Implications

On the face of it, implications for housing markets are obvious. Fewer people entering the region implies less demand for housing. Of course, what’s driving the population slowdown matters, too. Slower inflows of international migrants should bring welcome relief to a region where rents continue to surge (the simple average of annual rent inflation was 7% across the region in May according to the CPI), especially as construction of these types of units is on the rise.

The slowdown in interprovincial migration will also impact a very important source of ownership housing demand for the region. Attracted by a massive affordability advantage, the wave of interprovincial migrants over the past few years–with the largest share coming from Ontario–have bid up prices to a significant degree and eroded affordability in every market. In Nova Scotia and PEI, affordability has been stretched to near historic worsts, although the situation is somewhat better in New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador (Chart 3). Fewer Canadians are now choosing to move into the region from elsewhere in the country, blunting a force that was propping up home prices while leaving other residents of the Atlantic in a much worse affordability situation. Against this backdrop, we see home price growth slowing in the region next year, even with interest rates likely to decline (Chart 4).

Labour Market Implications

Slowing population growth across Atlantic provinces can also disproportionately impact labour markets. As economies were recovering from the pandemic, migrants from both the international and interprovincial migration channels contributed positively to local labour supply and employment growth. The downturn in population growth hasn’t yet translated to a slowdown in labour force growth, though we do expect a more pronounced effect on the labour force next year.

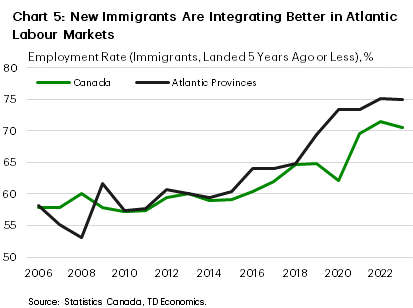

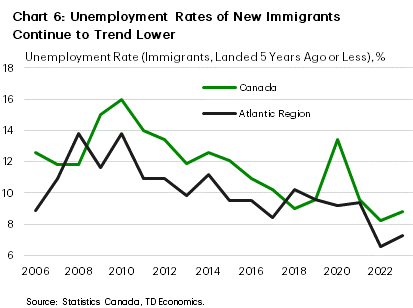

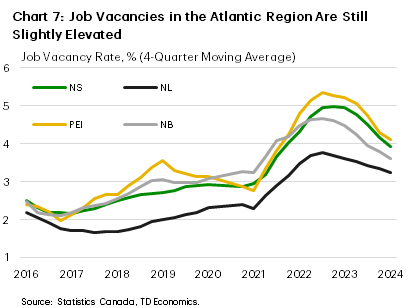

In the period from 2020 to present, immigrants across the Atlantic provinces experienced relatively better labour market outcomes compared to the nation as a whole. For example, immigrants landed 5 years or earlier are now seeing higher employment rates since the pandemic-recovery years compared to Canada (Chart 5). Historically speaking, the unemployment rate of new immigrants in the Atlantic region has hovered below that of Canada’s. Chart 6 shows that immigrants in the Atlantic didn’t experience the 2020 pandemic spike in unemployment rates that immigrants in the rest of Canada saw. Beyond this, the unemployment rate for new immigrants has continued to decline. In other words, Atlantic provinces are showing they are better able to absorb the wave of newcomers even as labour force growth picked up in line with the rest of Canada. This is part of the reason why total unemployment rates in the Atlantic region are rising at a slower pace than the rest of the nation while GDP growth prospects remain on the brighter side. Labour markets have indeed cooled in the Atlantic region alongside those of other provinces. However, if population growth slows faster than expected against a backdrop of still elevated vacancy rates (Chart 7), it may delay a full rebalancing.

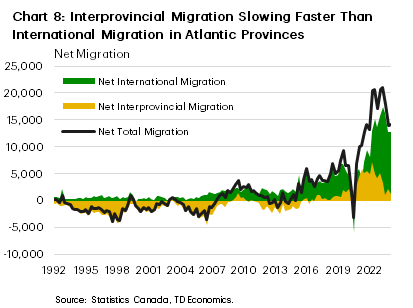

Source of the Slowdown

At a broad level, the deceleration of the Atlantic region’s population growth is being disproportionally driven by a slowdown in net interprovincial migration as opposed to international migration (Chart 8). At last count (Q1-2024), net interprovincial migration in the Atlantic provinces totaled just over 1,000 people, a significant pullback from the 5,000+ run rate between 2021 and 2022. Interprovincial migration is a relatively new source of population growth in the region. From 1992–2016 Atlantic provinces experienced net outflows through the interprovincial channel, so even the current (small) levels of inflows are greater than historical norms. Net international migration on the other hand is cooling but not to the same degree. Consistent with national level trends, non-permanent residents are still entering the country at a rapid clip in advance of federal policies aimed at curbing population flows.

On Federal policies, the effect of the government’s international student intake cap and non-permanent resident targets may impact Atlantic regions differently. For example, Newfoundland should be better insulated against the student cap, as is it the only Atlantic province to see their student permit allocations rise compared to 2023. The government’s intention to reduce the share of non-permanent residents to 5% of the total population may also come with varying implications. PEI for example, is currently the only Atlantic jurisdiction where non-permanent residents account for more than 5%, so non-permanent resident flows should slow quicker.

On the interprovincial side, flows in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia have more scope for a pullback as current levels are running well above their historical averages. The region as a whole however should continue to see modest positive interprovincial migration given the region’s affordability advantage, but these flows will remain well below peak levels in 2021 and 2022.

Bottom Line

While above-average levels of population growth are expected to persist in the Atlantic region in the very near-term, current trends are pointing to a faster slowdown in headcount growth compared to government estimates in 2025. While not necessarily a red flag, this does create a scenario for potential downside to economic growth via consumer spending and weaker job creation. At the same time, the housing market may benefit from slower rental price growth and easing affordability concerns. Federal government policies will work through the Atlantic region in various ways, with the common denominator being that all regions will see some form of population growth slowdown.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: