The Bank of Canada:

To Err is Human, To Forgive Is Divine, To Evolve Is Necessary

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

Date Published: January 11, 2023

- Category:

- Canada

- Financial Markets

There’s no shortage of articles criticizing the Bank of Canada (BoC) for its policy decisions and communication. However, those who live in glass houses should not throw stones.

During the pandemic, analysts encouraged the central bank to provide forward guidance. It was sometimes pointed out that its U.S. counterpart had greater transparency because it showed forecasts on the unemployment rate alongside the famous “dot plot” of the committee’s policy rate expectations.

Forward guidance, after all, comes right out of the playbook when a central bank wants to influence longer-term interest rates and broader financial conditions. It’s deemed a particularly effective tool when the policy rate is already at the effective lower bound (ELB), as in 2020. With no more downside room and with quantitative easing in full swing, forward guidance is the third and final pillar in achieving the desired path on inflation and economic activity. Unfortunately, this strategy backfired for the BoC.

To err…

BoC Governor, Tiff Macklem, will perhaps forever be remembered for these words in October 2020:

Let’s flashback to October 2020. Inflation was less than 1% and the country was in another COVID wave. Every central bank was delivering a similar message of “lower for longer” on interest rates. For instance, the Federal Reserve showed a strong committee consensus for a zero-policy rate in 2023.

To forgive….

The central bank should be forgiven for trying to inject calm and stimulate growth during a time of uncertainty. The mistake occurred when the Bank of Canada failed to evolve its guidance to the observable outcomes.

By mid-2021, vaccines were in full swing. There was plenty of evidence that the economy had escaped the peak risk period and that sustainably achieving the 2% inflation target required edging up the policy rate from its crisis level.

- The unemployment rate was about mid-7% – still on the higher side but showing a convincing downward trend every time government mobility restrictions were lifted.

- The federal government displayed a strong commitment to come to the rescue of the unemployed and businesses. In previous recessions, a typical rule was for program spending to amount to 2% of GDP. In this cycle, it hit double-digit levels and included bold expansions and new designs of programs.

- High household savings rates were readily observed in the data. This could be interpreted as a negative signal if the accumulation occurred due to an unwillingness to spend. But quite the opposite was occurring. Where consumers had access to spending, they readily jumped in. Spending on goods trended well above its pre-pandemic level and was even above the counterfactual analysis of where it would have been if the pandemic had never occurred.

- Home prices were already up 30% from pre-pandemic levels, also a resounding signal of household confidence.

- Risks related to household indebtedness were steadily rising and the uptake in variable mortgage rates was about to surpass the prior peak.

- Lastly, but certainly not least, inflation – the Bank of Canada’s formal mandate commitment – was trending and holding well above the 2% target.

Although the BoC had surpassed its intention, it failed to recognize or believe it. The question is why?

It wasn’t because of the dynamics of the pandemic. It was because the Bank of Canada was steeped in a one-sided bias that anchored their views. They relied too much on past observations, rooted in a set of heuristics or rules that prevented the evolution of thought. Simply put, the BoC was overly biased to “what was” rather than “what is”.

Long before the pandemic, the Bank of Canada spent several years researching the framework for renewing its inflation mandate. In December 2021, it published that interest rates around the world were likely to stay low in the future. Significant ink was also spilt on navigating the limitations this could present to monetary policy as a support to the economy. The reference to an “effective lower bound” showed up 71 times within the Bank’s inflation renewal mandate (not including footnotes and graphs!). The prospect of high interest rates and persistent inflation was not within the realm of analysis.

On top of that, the BoC entrenched a view that the use of the ELB would increase in both frequency and duration. BoC staff estimated the ELB to be 0.25 percent and the odds of it occurring due to an adverse economic event to be 17% in 2021, versus only 6% five years prior. Then, it estimated that the average duration for the policy rate to remain at the ELB would be longer going forward at about seven quarters versus prior episodes of 2.3 quarters.

This entrenched a mindset that playing it safe meant erring on the side of leaving interest rates at emergency levels, irrespective of the evolution of the data. The burden of proof required the data to not just convince the central bank that it would succeed in its inflation mandate, but to erase every millimeter of doubt. This occurred despite the Bank’s analysis that noted the importance of considering government stimulus in setting monetary policy, and the impact of home prices on lifting household inflation expectations.

To evolve…

History can’t be changed, but we can benefit from its lessons. The error was not in exploring a lower neutral rate, the resulting ELB of 0.25% or the limitations that can arise with monetary policy during an economic downturn. However, insufficient attention was paid to the other side of that risk.

In particular, household financial risks should not have been so easily dismissed or punted to regulators to manage. The consumer is king in the economy (i.e. >70% of GDP) and peer-country experiences have revealed household deleveraging cycles to be multi-year events that undermine long-term economic growth prospects. Regulators had already pulled on a half-dozen levers prior to the pandemic to manage housing financial imbalances, marked by changes in mortgage qualifications and amortization periods. The data had already shown this could only slow, but not stop the march of housing demand. It was no match for ultra-cheap financing and the strong demand that distinguishes Canada from many peer countries.

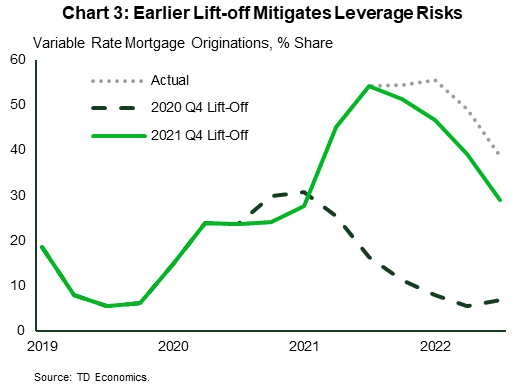

So, when the Bank of Canada followed its script, and left the policy rate at the ELB for eight quarters during the pandemic, it perpetuated an unprecedented degree of financial risks within the economy. For instance, the share of variable interest rate mortgage (VIRM) originations increased from 6% before the pandemic (Q4 2019) to 56% by the first quarter of 2022. Much of that escalation occurred in 2021, following the BoC’s “lower-for-longer” forward guidance. That guidance provided Canadians with the confidence to dive into a home purchase and created a preference for cheaper financing options. The spread between VIRMs and the 5-year conventional posted mortgage rate was already favourable at 155 basis points when the BoC offered its forward guidance. It rose to over 200 basis points by late 2021. For many homeowners and investors, this was a deal of the decade – last seen in 2011.

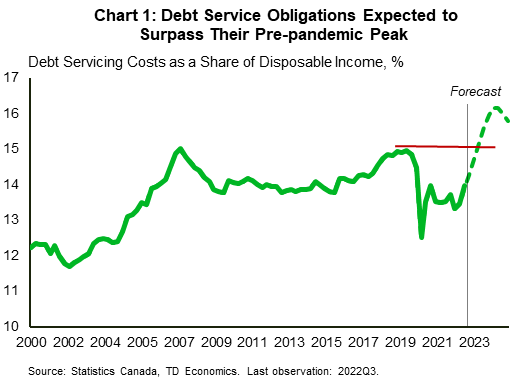

The repercussion was an injection of historic levels of household debt, within a population that was already described as being highly indebted. And this risk is about be amplified by historic debt service costs (Chart 1) that will steal growth-momentum from other areas of the economy. When economists are asked about the dominant risk to the outlook, this is it. Many foresee a deleveraging cycle as a necessary outcome.

Shortening up the duration of the ELB on the policy rate to evolving developments would have mitigated financial and inflation risks that now burden future economic growth. Greater credence should be given to two unique factors in Canada when deciding on how long to leave interest rates at an emergency floor level once the immediate crisis-event has passed.

The first relates to risk management. It’s no secret that population growth in Canada exceeds peer countries by a wide margin and this pressures home prices within a constrained geographic space. Roughly 60% of Canada’s population settles within 200 kilometers of only five cities. Rising government immigration targets could very well turn up the dial further on demand and price pressures. There’s nothing the Bank of Canada can do about the demand inflow, but the duration of applying a zero-policy rate long after the worst of the crisis moment has passed should consider its direct effects on fueling home prices, speculative behavior, and leverage. In other words, the housing market shouldn’t be passively viewed as a byproduct of monetary policy that’s left to regulators to manage.

The second factor that needs greater consideration on the ELB duration is the degree of accompanying government support. Once it was observed that government support programs were placing an unprecedented floor under households and businesses, this should have led to a shortening up of the ELB duration, and not a lengthening.

As we now look to the future, we may continue to see a stronger, or a more effective, level of government support relative to past recessionary episodes. For instance, the pandemic ushered in a review and broadening of government cyclical support programs, including an expansion of employment insurance. Other programs, like wage subsidies that encourage the retention of workers, may also come back into play during a crisis moment. On the structural side, large and permanent measures are unfolding, like $10/day daycare that will maintain a greater portion of after-tax income in the pockets of working households. The combination of these cyclical and structural programs, in their design, could lead to greater economic resilience relative to the household behaviors of past recessionary cycles. If so, this would shift the balance of risks related to leaving interest rates at the ELB for too long in Canada, irrespective of the decisions occurring by central banks in other countries.

Should have, would have, could have…

With hindsight, we can go back and consider the counterfactual outcome had the BoC shortened up the duration of the ELB once it became clear that risks were rapidly evolving around the inflation outlook and within the housing market, especially when government supports were creating extraordinary savings and hiring outcomes.

We ran two illustrative scenarios where the BoC moves off emergency level interest rates at an earlier phase in the cycle. The first scenario returns the policy rate to 1% by the end of 2020 and the second does so at the end of 2021. The first scenario is consistent with the Bank of Canada’s initial analysis of an ELB lasting roughly two quarters, while the second scenario fits with their updated view of roughly seven quarters. Granted, the first scenario of an early lift-off in 2020 would require a large leap of faith on the economic trajectory, even with a policy rate adjustment to only 1% (from 0.25%).

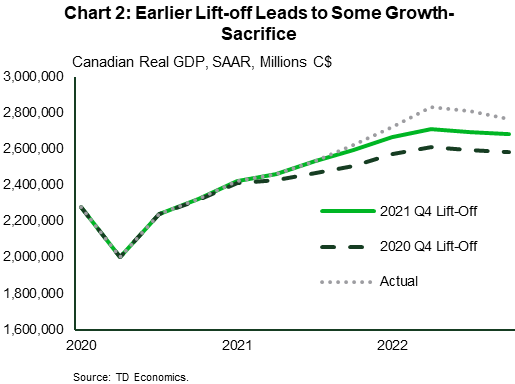

Not surprisingly, in both scenarios, the BoC would not need to hike as aggressively as today to manage the inflationary risks. Of course, there are trade-offs. Both initiatives would come with some sacrifice to GDP growth (Chart 2), but neither prevents the economic recovery from proceeding.

Both scenarios also lead to improved risk management of household finances that now expose the outlook to economic scarring. From Q4 2020 to Q3 2022, a cumulative 1,233,944 homes were sold across Canada. Under the 2020 lift-off scenario, we estimate that roughly 150,000 fewer homes would have been sold with an average price of about $35,000 lower. More importantly, this scenario corresponds with significantly less take-up of variable interest rate mortgages due to the resulting flatter curve across the term spectrum (Chart 3).

The 2021 lift-off scenario would be less material in preventing a peak in the share of VIRM mortgages, but it would have succeeded in “bending the curve” much earlier and lessening the economic risks. Naturally, there’s a lot of white space between these two scenarios with other policy paths that could have been chosen to strike a better balance between economic growth and risk management, relative to where we ended up today.

Bottom Line

Hindsight is a great instructor but not a practical tool in the moment. Better to focus the lens on avoiding bias that anchors to past dynamics that blind us to current developments. Forward guidance and a bias towards a longer duration on the ELB gave an additional boost to the Canadian economy, but it also amplified risks and contributed to the central bank reversing course on interest rates at a breakneck pace in its aftermath.

In the future, we are unlikely to see the unprecedented level of government spending to households from the pandemic, but a legacy will persist in the evolution of programs in response to economic shocks. With more effective countercyclical fiscal policy, monetary policy should be more attuned to the pitfalls of leaving policy rates too low for too long.

There should also be greater responsiveness to the risks ELB imparts to financial imbalances, particularly when related to the largest liability holdings of household balance sheets and Canada’s unique position here.

It’s long been known that monetary policy is not a science, there is a lot of judgement involved. The Bank of Canada has few tools at its disposal to manage the entire economy, but one thing endures through time – interest rates are powerful and permeate every corner of the economy. With great power comes great responsibility.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: