Highlights

- Despite the hardships of the pandemic, the Canadian economy has staged an impressive recovery over this past year. This would not have been possible without the increasing use of technology by households and businesses.

- While the digital transformation has built up the economy’s resilience to the impacts of the health crisis, workers displaced by new technologies may have challenges finding employment in the post-pandemic economy.

- The industries hardest hit by the pandemic face the greatest risk of transformation due to automation and digitalization. Some of the jobs lost in last 12 months will never come back.

- Affected workers will need time to find new jobs and develop new skills. Fiscal and monetary policy will need to remain supportive in order to ease the transition and return the economy to its full potential.

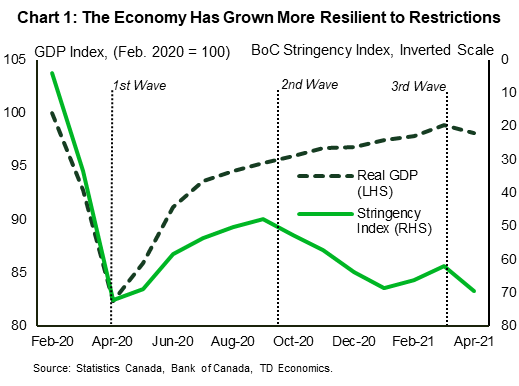

Elevated health concerns, social distancing protocols, and business and school closures have made for a difficult year for the Canadian economy. Despite these hurdles, the economy has been on a steady march towards recovery since initial lockdowns in the spring of 2020 (Chart 1). GDP improved even as provinces tightened restrictions from October 2020 through January 2021 as the second wave of the pandemic hit. In January this year, GDP advanced 0.7% month-on-month, even with restrictions that were almost as stringent as they were at the onset of the health crisis. Early indications are that GDP will contract in April for the first time in 12 months as a result of third-wave restrictions, but it will probably not blow the economic recovery off course.

Clearly, the Canadian economy has grown more resilient to the impact of the pandemic and associated restrictions. A crucial element to this story is an increasing use of technology by Canadian households and businesses.

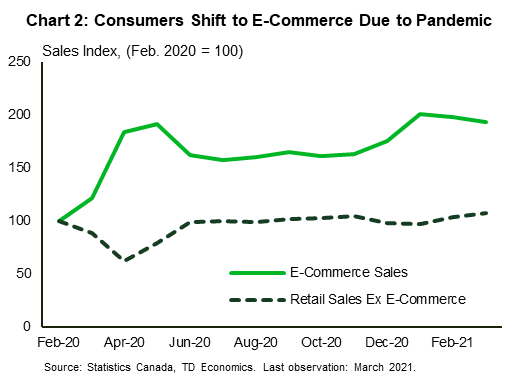

Technology, whether in the form of automation or digitalization, has jumped during the health crisis. The clearest example of this is online shopping. E-commerce sales have flourished during the pandemic, and now stand nearly 100% above where they were in February 2020 (Chart 2). According to a report by the Business Development Bank of Canada, eight out of 10 Canadians who made online purchases for the first time during the health crisis, said they would keep doing so going forward.

The rise in online shopping would not have been possible without businesses building out digital infrastructure to meet consumer needs. Whether goods or services, firms enhanced their virtual platforms to make conducting online transactions easier. A recent survey of Canadian executives by Modus Research reported that nearly 25% had taken measures to build or expand online sales.

Technology has allowed other businesses to maintain operations over the last year. Firms that could, implemented work from home policies at the beginning of the pandemic. This required heavy investment in technology, allowing employees to do their jobs efficiently from home. As this transition occurred, some employers even made the decision to move to a remote work set up permanently.

Some of these pandemic-induced changes will remain in place after the health crisis. Canadians have become more accustomed to online shopping, businesses to delivering their products virtually, and employers to accommodating employees working from home. These structural shifts will have important implications for the labour market recovery.

Jobs in the Hardest Hit Sectors Most Affected by Increased Technology Use

This is not the first time that the adoption of technology has sent tremors through a country’s labour market. Recent research has found that the increased use of industrial robots reduced employment and wages between 1990 and 2007 in the U.S. with the biggest negative impacts on workers with less than a college degree.1 While the current episode of digitalization and automation may not introduce a shock of equal magnitude, it will transform some jobs while eliminating others.

The occupations facing the greatest risks of disruption are service-sector jobs in areas worst impacted by COVID-19. In a report released in June last year, Statistics Canada estimated the risk of automation faced by Canadian workers across a broad set of occupations.2 According to this analysis, service sector positions, specifically in office support, specialized services (i.e. hairstylists, chefs, etc.), wholesale and retail trade, and other customer services, face the highest risk of transformation due to automation (Table 1). Industrial, electrical and construction positions similarly faced elevated risks from automation.

Table 1: Occupations Facing The Highest Risk of Job Transformation and Employment Gap

| Occupation | Risk of Job Transformation | Employment Gap in May 2021 Relative to February 2020 (Thousands) |

| Office support | 36% | 25.3 |

| Service supervisors and specialized services | 20% | -91.5 |

| Industrial, electrical and construction | 20% | -50.5 |

| Salespersons - wholesale and retail trade | 15% | -45.3 |

| Service reps and personal services | 14% | -200.8 |

Out of the five aforementioned occupation types, four have seen employment plummet due to the pandemic. In fact, these occupations account for nearly 80% of the overall employment deficit compared to pre-pandemic levels. On the flipside, despite the highest risk of job transformation, office support jobs are currently in surplus territory, with the level of employment 25k positions above its February 2020 level.

Digital technology is unlikely to replace all the jobs still in deficit (at least in the near-term). Reopening of the economy will spur a rebound in high-touch service sector employment. Still, some jobs may never return. The rise of e-commerce enabled retail and wholesale businesses to see gains in sales with fewer workers relative to the pre-pandemic period. If consumers do not make a full return to instore shopping, there will be less demand for salespersons. Similarly, the greater prevalence of work from home will mean less workers return to office buildings, which could weaken demand for janitorial and building maintenance staff. At the same time, food establishments that had once served office workers may have to eliminate positions given the permanent reduction in foot traffic.

Greater Technology Adoption Presents Long Lasting Shock to Labour Market

While some jobs disappear, others will take their place. More online shopping will increase the demand for warehouse workers. Likewise, office building janitors may become housekeepers, as people spend more time working from home. For some workers, the transition to a new job in the post-pandemic period will be relatively straight forward, for others it may be a lot more challenging.

In this sense, the pandemic represents a labour reallocation shock. Employment conditions are strong in some sectors, but weak in others. Individuals with skills in digital technology are likely to be in high demand, but those in more traditional retail roles may not be. These workers will have to retrain to acquire expertise in this regard. This will prolong the labour market reallocation process.

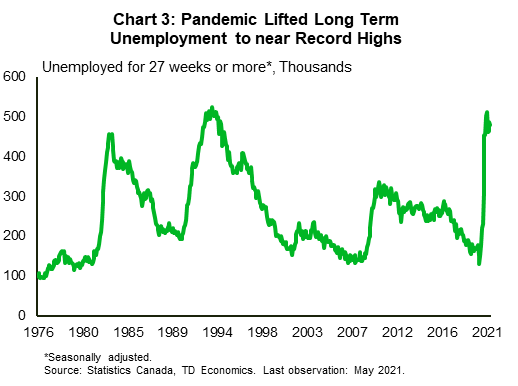

Along with the skills mismatch, the job search could be protracted for individuals who have been unemployed for a very long time. A deterioration in existing skillsets combined with the need for new digital skills will create challenges, even for those looking to remain within the same industry as their previous occupation. Currently, due to the COVID-19 health crisis, the number of workers who have been without work for 27 weeks or more is near record highs (Chart 3). The last time the number was this elevated was in the early 1990s, when it took nearly a decade to return to pre-recession levels. While the pandemic recession is unlike past downturns as reflected by the rapid rebound so far in GDP and employment, skills erosion is still occurring. This suggests long-term unemployment will take time to return to pre-crisis norms.

Programs introduced in the federal government’s 2021 budget could help ease the impact of the labour reallocation shock. Funding for recruiting and training workers in digital technologies, connecting unemployed individuals to new opportunities, and subsidizing education for working adults, can speed up the labour market recovery. Indeed, in a recent report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that, given the pandemic-induced digital transformation, policies that support the reallocation of labour are more effective in reducing unemployment in the economy.3

Still, in the near-term, the labour market recovery could be bumpy as the economy reopens. Akin to what is currently being observed in the U.S., we can expect reports of staffing shortages in the coming months. Workers may not return to their old jobs either because there’s no job to go back to, or they’d prefer a new occupation. Both of which could dampen the employment rebound.

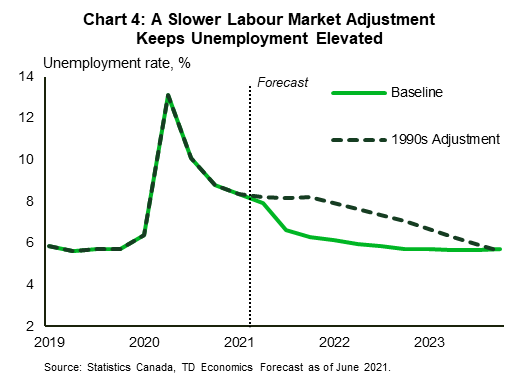

Our recently updated forecast anticipates the unemployment rate will to return to 2019 levels towards the end of 2022. But there is a chance that it takes longer for the labour market to heal. If the recovery is similar to what occurred in the 1990s, the unemployment rate could remain elevated for longer (Chart 4). In fact, it would only return to its pre-pandemic level by the end of 2023, a full year after our baseline assumption.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) will be watching labour market developments closely as it deliberates the future of monetary policy. In a recent speech, Deputy Governor Timothy Lane noted that the increased pace of digitalization during the pandemic could raise productivity, but at the same time, it could displace workers, leaving many Canadians without jobs for some time. The BoC expects this “economic slack” to only be absorbed in the second half of 2022, in line with our baseline forecast.

But the Bank is acutely aware of the downside risks. If the digital transformation is deeper, and more workers are permanently displaced by technology, it could take even longer for the labour market to recover. In this scenario, economic slack would not be absorbed in 2022, and the Bank will have little choice but to keep monetary policy loose until labour market conditions sufficiently tighten.

The embrace of digital technology during the pandemic supported the economy through the depths of the health crisis. But as we look ahead, it could weigh against the employment recovery as the economy reopens. Impacted workers will need time to find new jobs and develop new skills. Fiscal and monetary policy will need to remain supportive in order to ease the transition and return the economy to its full potential.

End Notes

- Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets”, Journal of Political Economy, 2020.xx

- Marc Frenette and Kristyn Frank, “Automation and Job Transformation in Canada: Who’s at Risk”, Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, June 2020.

- IMF, “Recessions And Recoveries In Labor Markets: Patterns, Policies, And Responses To The COVID-19 Shock”, World Economic Outlook, April 2021.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: