Potential Hazards Ahead:

Trade Risks in the North American Automotive Industry

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: January 28, 2025

- Category:

- Canada

- Trade

- Commodities & Industry

Highlights

- The automotive industry accounts for over 10% of intraregional trade in North America, equating to hundreds of billions of dollars in cross-border trade flows and millions of jobs.

- Proposed blanket tariffs of 25% on Canada and Mexico, if retaliated against in equal measure, would likely result in a material contraction in vehicle sales in all three North American nations as price increases would ripple through supply chains.

- The broader negative economic outcomes associated with this scenario would likely limit its political durability, but the North American auto industry should still prepare itself for a prolonged period of elevated trade uncertainty and potential trade disruptions.

Free trade in automobiles has existed in North America for over sixty years. First bilaterally between the U.S. and Canada when the Automotive Products Agreement was signed in 1965 and subsequently enhanced by the U.S./Canada Free Trade Agreement (1989). Free trade then became trilateral with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1997, when Mexico joined the trade union, and updated by the 2020 U.S.-Canada-Mexico Agreement (USMCA).

With deep historical roots, it is unsurprising that the automobile industry is one of the most highly integrated in North America, with parts sometimes crossing a border half a dozen times before final assembly of a vehicle. This highlights the acute vulnerability posed to the industry, including the hundreds of billions of dollars in regional trade it generates annually, by potential tariffs that have been proposed by the new U.S. administration.

North American Auto Trade Overview

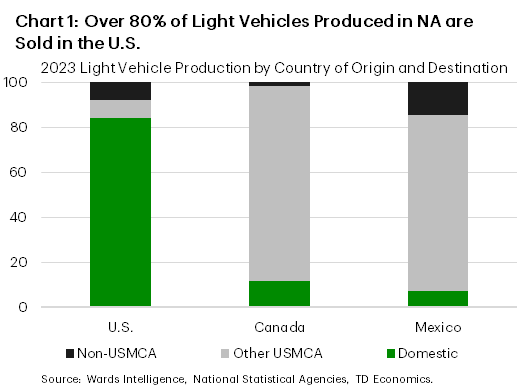

The structure of North American automotive production is centered around its largest consumer market. Over 80% of vehicles produced in North America are sold in the U.S., with most of these vehicles being produced domestically. However, the U.S. also imports millions of vehicles from Canada and Mexico every year, with the vast majority of vehicle exports in these two countries destined for the U.S. This creates an interesting dynamic, where Canada and Mexico both produce vehicles almost exclusively for exporting purposes, whereas the U.S. produces vehicles primarily for domestic consumption (Chart 1).

The primary reason why this integrated market structure has arisen is owing to the high volume, low variety production methods used in the automotive industry. The larger the market, the more optimal these methods become in terms of meeting diverse consumer preferences. This also explains the centralization of the industry in the U.S., as two-thirds of North America’s population and nearly 90% of its annual economic output is located in the country. These factors also aided the U.S. in developing domestically owned, mass-market automakers at the turn of the last century, something Canada and Mexico do not have.

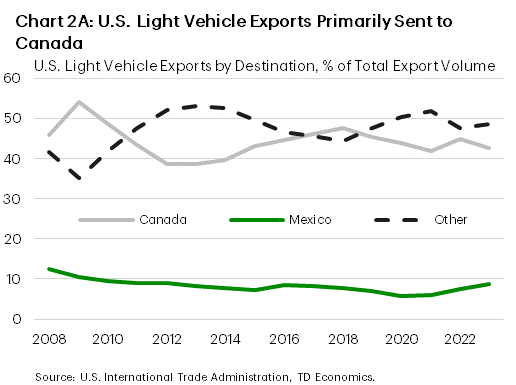

For its part, the U.S. also exports roughly 1 million automobiles to Canada and Mexico annually, with the two countries accounting for half of all U.S. light vehicle exports. However, these trade flows are not equally distributed between Canada and Mexico, with Canada consuming more than 40% of all U.S. light vehicle exports in any given year (Chart 2a), making Canada by far the largest automobile export market for the U.S.

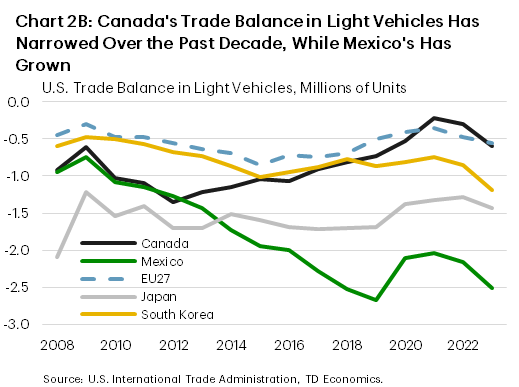

In terms of total volume trade balances in light vehicles, the U.S. deficit with Canada has become progressively narrower over the past decade (Chart 2b). In contrast, the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico in light vehicles has become notably larger after previously tracking closely to Canada in the early 2010’s. The U.S. trade deficit in light vehicles with other countries, such as the EU, Japan, and South Korea, has remained relatively steady over the past decade.

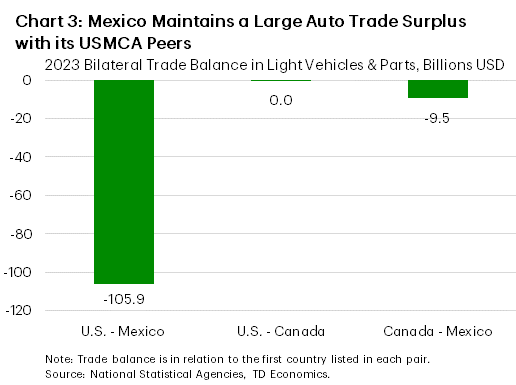

Expanding further to look at total trade in automobiles & automobile parts, Canada’s trade with the U.S. was fully balanced in 2023, while Mexico maintained a significant trade surplus in both automobiles and parts. Mexico’s total trade surplus with its North American trading partners in automobiles & parts in 2023 was over $115 billion (Chart 3). To ascertain how Mexico came to hold this position, we need to examine trends in North American production and sales more closely.

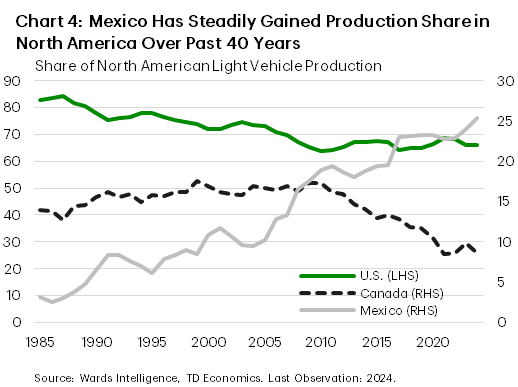

The first point to make is that North American automotive production has been gradually shifting towards Mexico for the past forty years, with a marked acceleration occurring in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis (Chart 4). In 2024, Mexico accounted for 1-in-4 vehicles built in North America, notably higher than its 10% share in 2000. In that time, the U.S. share has fallen by 6.1 percentage-points (ppts) and Canada’s share has fallen by 8.4ppts. The U.S. has remained the outright dominant producer, accounting for two-thirds of regional production, but Mexico’s gains allowed it to supplant Canada as the second largest producer in 2008.

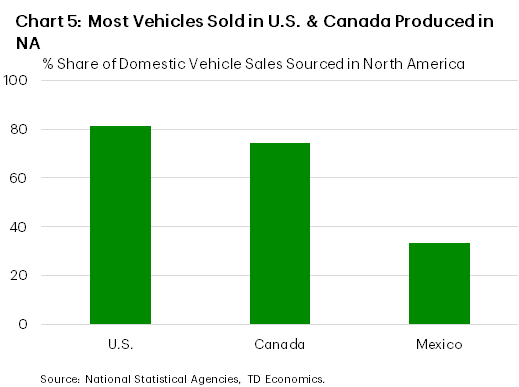

In addition to its growing share of regional production, Mexico’s consumption of automobiles has also shifted away from North America over the past decade. In the U.S. and Canada, more than 75% of light vehicle sales in each country were sourced in North America in 2023, while the same number in Mexico was roughly one-third of sales (Chart 5). One of the main reasons for this is that Mexico purchases far more vehicles from China than either Canada or the U.S. In fact, Mexico purchased more vehicles from China than the U.S. in 2023, marking the first time that the U.S. was not the primary source of Mexican vehicle purchases. In contrast, Chinese produced vehicles have a very limited presence in U.S. and Canadian light vehicle markets – a fact unlikely to change in the near term amid growing trade tensions.

The trend of Mexico continuing to gain a larger share of North American light vehicle production, while simultaneously shifting its procurement of vehicles away from the region is likely to be a point of contention in the upcoming USMCA review in 2026. Mexico is likely to maintain that this trend is simply a by-product of comparative advantage (both in terms of its domestic production capabilities and the relative cost advantage of Chinese automobiles). The U.S. and Canada will likely counter that China’s cost advantage comes from a state-directed policy of over-capacity and anti-competitive ‘dumping’ practices (deliberately selling goods for cheaper abroad to gain market share). Working towards establishing a common regional approach to China is likely to be a recurring theme during the upcoming review of the USMCA.

The Prospect of Regional Production Reorganization

The concept of re-shoring industrial production has been a common theme in the statements related to trade made by President Trump on the campaign trail and since his inauguration. He has used the automobile industry as an example on several occasions over the past few months, and last October even stated that he would levy tariffs as high as necessary to keep Mexican produced vehicles out of the U.S. market. More recently, he also indicated that Canadian vehicle imports could be replaced by ramped up production in Detroit.

Uninterrupted free trade in the sector has existed for decades, allowing for economies of scale to be achieved by automakers, lower prices for consumers, and economic benefits to be shared between the three countries. Suffice it to say that disrupting these trends through tariffs or other penalties on Canada and Mexico to gain a higher share of the automotive market would come with significant costs.

Fully reshoring the production of the volume of vehicles that the U.S. imports annually would theoretically be feasible. Adding 7-8 million units in production capacity would come with a price tag of roughly $50 billion. Not small change, but manageable for a country that outlaid over $100 billion in Inflation Reduction Act subsidies for manufacturing projects and recently announced a $100-500 billion investment in artificial intelligence infrastructure. The price tag would also likely be under $50 billion, assuming some of the existing U.S. production can be leveraged to meet the higher production volume. The caveat is that these costs would likely be borne largely or in entirety by the private sector, meaning the higher costs would be passed on to American consumers.

In addition, production volumes are only one piece of the puzzle. Americans consumed more than 328 different vehicle models in 2024, while only producing 121 model types. Automotive production is highly specialized, with only 2-3 models being produced at most assembly facilities. This disconnect between production variety and consumption is the underlying reason why a larger integrated market is optimal for light vehicle production.

Putting aside the notion of fully reshoring U.S. production, its important to note that even a partial reshoring would still come with complex logistical challenges. The current organization of automotive supply chains is highly integrated across North American borders, which would pose challenges to regional reorganization that would be greatly amplified if tariffs were imposed.

Trade Disruptions in a Unified Market

Despite the USMCA being negotiated by President Trump during his first term, the President has announced that he intends to deviate from the agreement unilaterally to impose a blanket tariff on Canada and Mexico of up to 25% as early as February 1st.

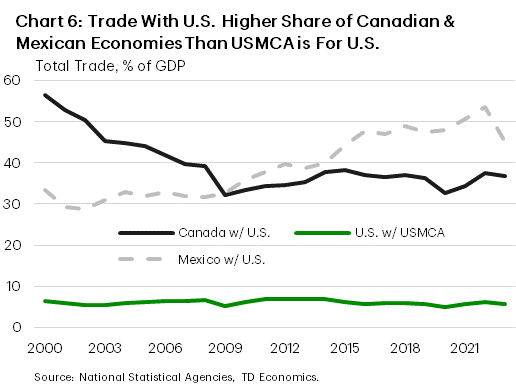

The economic impact of a sustained 25% tariff on Canada and Mexico would be severe, with full tit-for-tat retaliation likely to push Canada and Mexico into a recession and the U.S. to a point of stagnant growth. The economic impact would be larger in Canada and Mexico owing to the importance of North American trade to each economy (Chart 6), but the likelihood of additional tariffs being implemented by the U.S. against its other trading partners would still result in a material hit to GDP growth. These tariffs would directly raise prices for domestic consumers and businesses, likely putting downward pressure on household disposable incomes and firm profit margins. As this weakens economic growth, employment levels would be expected to decline, raising the unemployment rate. A period of stagflation (weak growth, high inflation) induced by fiscal policy creates a complicated situation for central banks, which are more likely to make a mistake than not in such an environment. Lowering interest rates to stimulate growth would be the most likely outcome, but the risk of higher inflation becoming entrenched, especially in the U.S. where inflation currently remains above target, could keep rates significantly higher than otherwise would be desired.

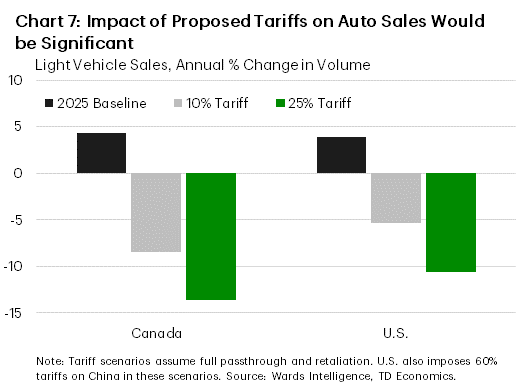

With these tariffs in place, we would expect to see vehicle sales in these countries contract substantially (Chart 7). This is driven by both the direct impact of notably higher vehicle prices, in conjunction with the indirect economic impact occurring in the broader economy from the blanket nature of the tariffs. Even if the Trump administration opts to implement a lower tariff, a 10% tariff would still be expected to weigh on sales this year. As most vehicles sold in Canada and Mexico are imported, the direct impact on sales would likely be higher in these countries. However, given the level of integration in North American automotive supply chains, it is highly likely that U.S. sales would be hit even absent retaliatory trade measures from Canada and Mexico.

President Trump opted to refrain from imposing tariffs on his first day in office, but instead used an executive order titled the “America First Trade Policy” to outline a broad review of the nation’s trade. Section 2d of the order instructed the U.S. Trade Representative to begin an assessment of the USMCA for the upcoming 2026 trilateral review, with a report expected by April 1st. This is a necessary formality for the 2026 review, but the April 1st deadline is earlier than expected for this process. President Trump is likely angling for an earlier review, and may even revert to his first term playbook of threating to withdraw from the USMCA (then NAFTA) to gain concessions from the country’s two largest trading partners. The 2026 review only offers countries the option to indicate their intent not to extend the agreement when it ends in 2036, but any country can withdraw from the USMCA with six months’ notice. There is some uncertainty regarding whether the President has the power to terminate trade agreements, given that they are ratified by Congress, but any attempt to do so would still be expected to result in significant trade disruptions.

In the near-term, the President’s threat of imposing tariffs of 25% against Canada and Mexico remains the highest risk. Following up on these threats, the America First Trade Policy included instructions for the Departments of Homeland Security and Commerce to investigate the flows of unlawful migration and fentanyl into the U.S. from Canada, Mexico, and China. These investigations could result in punitive trade measures, but likely not before President Trump’s proposed date of February 1st. This means President Trump would have to use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act - a statute granting the President broad authority over trade measures - to declare a national emergency and implement tariffs by this date.

In terms of tariff options, there are limited restraints on the options available to President Trump. Even if the President opts to exempt the auto sector from steep tariffs in the near term, with the USMCA review less than a year away, the North American auto industry should prepare itself for a prolonged period of elevated trade uncertainty and potential material trade disruptions.

Bottom Line

Given the inherent complexity of automotive supply chains in the region, the risks associated with potential disruptions stemming from tariffs would likely be significant, with economic and industry specific impacts that would span all three countries. Grievances with the current state of regional trade should be raised under existing dispute settlement mechanisms of the USMCA, or alternatively, raised during the first joint review of the agreement next year. Unilateral deviations from the USMCA outside of these mechanisms that either directly or indirectly target the automotive industry are likely to result in material trade dislocations, higher costs for consumers, and slower economic growth.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: