Market Insight:

The Central Bank View of Inflation

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: June 9, 2021

- Category:

- Canada

- Forecasts

- Financial Markets

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Orlando, CFA, Senior Economist | 416-413-3180

Date Published: June 9, 2021

Investors are jittery over hot inflation metrics, as supply chain dislocations and the sudden snap-back in consumer demand blur the line between permanent and transitory price pressures. And who can blame them? In a business cycle like no other, prices are escalating from commodities to cars to food to a broad range of consumer services where price-inertia would typically rule the day. Central bankers are starting to feel the heat with investors questioning whether emergency levels of monetary policy remain appropriate alongside the extraordinary levels of fiscal policy supports.

Investors are jittery over hot inflation metrics, as supply chain dislocations and the sudden snap-back in consumer demand blur the line between permanent and transitory price pressures. And who can blame them? In a business cycle like no other, prices are escalating from commodities to cars to food to a broad range of consumer services where price-inertia would typically rule the day. Central bankers are starting to feel the heat with investors questioning whether emergency levels of monetary policy remain appropriate alongside the extraordinary levels of fiscal policy supports.

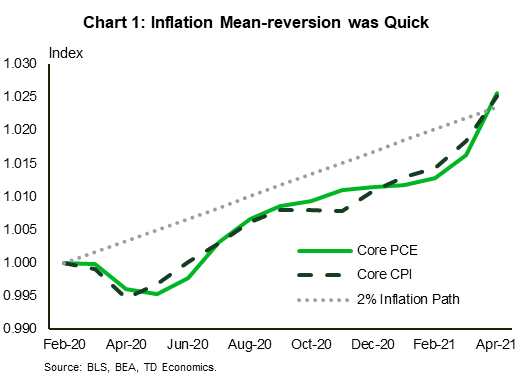

Although inflation has been a talking point for several months, a 0.9% month-to-month jump in core CPI got everyone’s attention. This was the highest monthly increase in 40 years, compelling Fed Vice Chair, Richard Clarida, to note that this “was well above what I and outside forecasters expected.” It wasn’t just the monthly advance in prices that was surprising. On a level basis, both core CPI and the Fed’s preferred inflation measure (core PCE) have already returned to where they would have been if inflation had grown uninterrupted at the Fed’s 2% target throughout the pandemic (Chart 1). Simply put, mean-reversion was quick.

Though the advance in inflation has been very strong, it’s too early to sound the alarm bell. We don’t think the central bank has fallen behind the inflation curve on monetary policy. Patience will be required, as it could take the remainder of this year (at least) to iron out the supply-side pressures. Turning the “economy back on” by removing self-imposed restrictions is like opening the starting gate of a penned in racehorse.

As next year unfolds, those 3-to-4 percent handles on the inflation metrics should give way to 2-percent handles. But that doesn’t mean the central bank is in the clear. The winds will be shifting from price pressures driven by transitory supply-demand mismatches to traditional demand-push forces from an economy closing in on full employment. This is what will keep inflation from not repeating the post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) experience where it serially undershot the Fed’s target. The speed of this economic recovery is like no other, and the Federal Reserve will have to be careful not to lean too heavily on the GFC historical context. We’re in the camp that by the end of next year, a necessary first step will take place in the rate hike cycle.

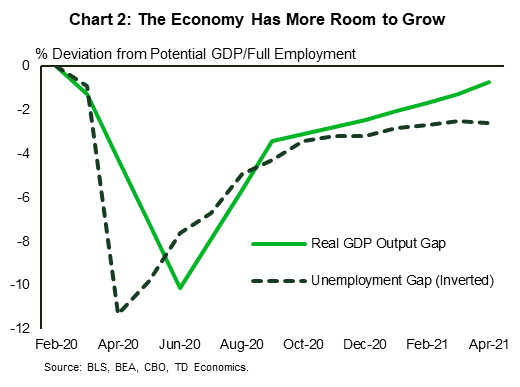

Understanding the future path of inflation will require gut-checks on whether the run-up in prices carry transitory markings. For instance, inflation has caught up to trend, but GDP has yet to do so, and the unemployment rate is even further behind from that marker (Chart 2). When a gap exists, inflation would have difficulty permanently staying above 2% because it has insufficient sustainable demand- and wage-push dynamics.

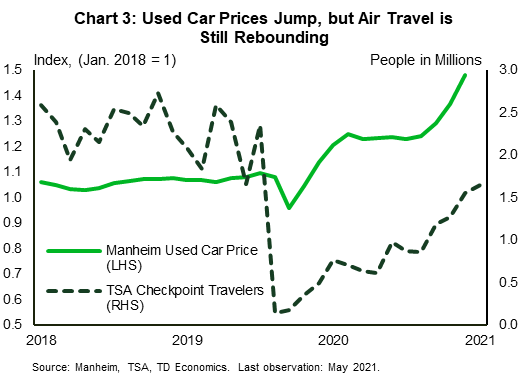

However, the weight of the pandemic on the economy is sending cross-signals in how it is manifesting in unusual price patterns with little historical context. The auto sector is the poster child of this. Prices for used vehicles skyrocketed under a chain reaction of events (Chart 3). First, people’s transportation preferences shifted to vehicles and away from air travel and public transit. This transitory influence is already starting to normalize. Simultaneously, a global shortage in semiconductors limited the ability of auto manufacturers to respond with new car production. This too occurred under surging pandemic demand for electronics and other items that competed for semiconductors, while several idiosyncratic factors also hit supply production, such as a fire in a large production site in Japan. This supply-side pressure will resolve, but manufacturers vary on their predictions of the adjustments occurring sometime between the third quarter of this year and mid-2022. Lastly, as new car supply tightened, unlikely buyers started to compete within the retail market. Rental agencies normally add supply to the used car market as they replace aging and depreciating stock. In a twist, they not only held on to their existing fleets, but also became buyers of used vehicles in order to circumvent shortages in the new car market.

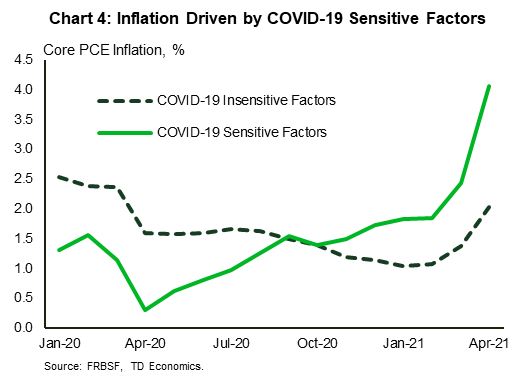

The auto sector is a stark example of how the pandemic disrupted supply chains. The issue is that this is also occurring across a broad spectrum of goods and services. Researchers at the San Francisco Fed separated the components of core PCE inflation into COVID-19 sensitive and insensitive groupings (Chart 4). The “sensitive group” is clearly driving inflation higher and accounts for a little more than half the recent rise in core PCE inflation. The researchers also provide a detailed breakdown of pandemic sensitive inflation into supply and demand factors. The data reveal that demand factors (from lost income) were a major drag on inflation for most of the last 16 months, whereas supply factors were lifting inflation. With the demand-side trends now reversing, it is compounding the supply factors that are forcing inflation higher. Since the supply-side will take time to resolve under differing lags and lingering effects by product, this year will capture a sizeable shift in inflationary pressures that some might find unnerving.

So far, the Federal Reserve is exhibiting nerves of steel in its reluctance to pull the interest rate trigger, in part because they don’t want a repeat experience of the post-GFC business cycle where inflation serially underperformed expectations.

We caution on becoming too wedded to the experiences of the past because none exhibited the speed of this recovery. Following the GFC, it took 10 years for GDP to return to potential and for the unemployment rate to return to “full employment”. In contrast, this cycle is moving at the fastest clip on both fronts in 75 years. The unemployment rate is estimated to be at full employment by the end of next year. Having a policy rate still sitting at zero at that time now becomes a lopsided risk of exaggerating forces to the upside on inflation, as the economy presses deeper into excess demand territory. And, should this occur, those pandemic-related transitory supply-side factors could then persist longer.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) is in a similar situation as the Fed. Headline CPI is up 3.4% over the last year and 7.1% month-on-month (annualized). When you strip out food and energy, the monthly increase is over 10%. The average of the BoC’s three core inflation metrics is also holding solid, up 2.1% year-on-year. That compares to only 1.6% last summer. Though some of the move is certainly transitory, Canadians are still feeling the pinch. Everything from clothing to personal care products are increasing dramatically.

What’s unusual for Canada is that this is occurring a bit prematurely. Much of the country was still under tight restrictions relative to the U.S. The supply-demand mismatch won’t reveal itself until lockdown restrictions ease through the summer. And the elevated Canadian dollar should temper import price pressures, while the U.S. has the opposite forces at work.

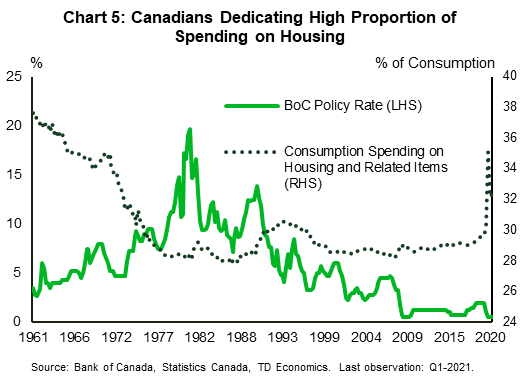

In addition, Canada is experiencing stronger forces in the housing market and related debt accumulation relative to its southern counterpart. The 20%+ rise in house prices is top of mind for most Canadians and the Bank of Canada. The amount that Canadians spend on their homes now makes up 32% of total consumption (on average over the last year). That is the highest allocation to housing in nearly 50 years (Chart 5). The last time Canadians spent so much on housing, it coincided with the pre-1970s low interest rate environment, rapid population growth, and a corresponding huge increase in house prices. Having the Canadian economy highly dependent on housing and related activities is reflective of an imbalance in the economy. All this points to an ongoing incentive for the Bank of Canada to further reduce its Quantitative Easing (QE) program in the coming months and signal the start of the rate hiking cycle in 2022. This has already started to lift government bond yields and force mortgage rates off the floor – a trend that should continue into the end of this year. We have the Canada 10-year government yield reaching 2% at the end of 2021 and 2.25% in 2022.

Over the last year, the Fed has been steadfast on its messaging. It has communicated that it will provide emergency levels of monetary policy support and is not ready to even think about adjusting the course. But the April minutes to the Fed meeting revealed a subtle and important shift in tone. Right at the end of the document, there was a little nugget that stated, “a number of participants suggested that if the economy continued to make rapid progress toward the Committee’s goals, it might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases.” We went from the Fed not willing to even debate a change in policy, to some members of the Fed believing a change to QE will be warranted soon. Right after the release of the minutes, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard commented on the QE policy, stating that “we’re not quite there yet, I think we will get there in the months ahead.” Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan agreed stating, “maybe taking the foot gently off the accelerator would be the wise thing to do.” The openness to changing policy has arrived. Even though this is coming from a small chorus of the Fed, we think the rhetoric will continue.

We believe the Fed will be in a position to adjust the QE policy stance before this year is out. Just like in 2013, this change may raise market expectations for future rate hikes and the overall yield curve with it. While rate hikes have started to be priced by markets, there is still more to come. Even though some Fed members are starting to lean into the idea of the rate hike cycle starting in 2022 or 2023, the unified messaging of the Fed hasn’t yet signaled this intention. We will be closely listening to remarks by Fed Chair Powell and Vice Chair Clarida, who have been calling for more evidence that the economic recovery is well underway. Though we’d agree that all the evidence isn’t in yet, the swiftness of this economic cycle is likely to soon prove unambiguous. By this time next year, we think the U.S. economy will have GDP rising above its potential, the unemployment rate will be back below 4%, and core inflation will be running around 2.5%. Keeping rates at the floor will seem out of place under that economic backdrop.

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.