Highlights

- The tightness of the Canadian labour market is most apparent in the elevated level of job vacancies across the country. This is causing upward pressure on wages and complicating the Bank of Canada’s ability to bring down inflation.

- We find that vacancies are most pronounced in low wage sectors that were hardest hit by the pandemic. With many workers having left these sectors in search of higher pay, firms may be unable to fill these job openings.

- The most likely solution to the job vacancy gap in Canada is an economic slowdown that reduces demand for workers and brings the labour market back into balance.

The Canadian labour market has led the economic cycle for much of the last two years. During the pandemic recovery it was gains in employment that catapulted Canada to the front of the global economic stage. The success resulted in a labour market tightening where the supply of available workers was no longer enough to meet continued increasing demand from businesses. We have seen the impact of this in the number of job vacancies, which at 958 thousand at last count in August 2022, implies there is nearly one job opening for every unemployed person.

As we know from Econ 101, when you have supply that can’t meet demand, the price goes up. No surprise that we have seen a steady acceleration in wage growth this year. And even with the recent softening in employment data over the last few months, there remains a supply/demand imbalance that is putting upward pressure on wages. It is no wonder that Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Tiff Macklem has focused on job vacancies in recent speeches. The Governor knows that closing the vacancy gap is imperative to achieving the goal of price stability.

Digging into the gap

Before we can address how the vacancy gap can be closed, we need to discuss how we got here in the first place. There have been a multitude of reasons proposed for why vacancies have been so elevated. Obviously, the rapid recovery has played a huge part, with the economy clearly overshooting its potential. But there is much more to this story. Some have argued that posting a job online has become so easy that hiring managers have become trigger happy. This points to the argument that many of the postings aren’t ‘real’, and that firms have learned to operate without filling certain jobs. In this case it will just be a matter of time before employers get around to canceling their excess job postings.

There is also the broader argument that there is a skills gap, where the current Canadian labour force isn’t equipped to do the jobs that are in demand. When Statistics Canada recently surveyed businesses on the skill level of their workforce, most industries reported they had a significant skills gap. Though this can explain why employers are struggling to find employees with the right skillset, the existence of a skills mismatch within their current workforce argues that this is not preventing firms from hiring.

Workers having their say

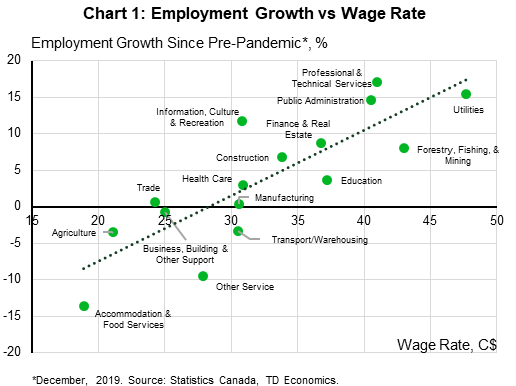

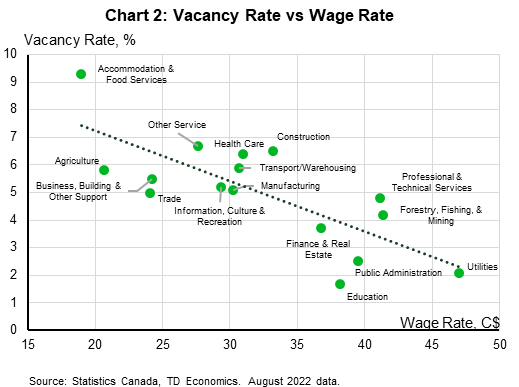

The arguments made above certainly explain the reasons for the vacancy gap from the perspective of employers, it is also important to look from the perspective of workers. When the pandemic hit, many workers in low wage sectors lost their jobs. And with numerous lockdowns that slowed demand in the hardest hit sectors, many of these workers looked for jobs in other industries. Fortunately, a rapid rebound was occurring outside of high-contact sectors. This gave workers a tremendous opportunity to increase their pay. Indeed, when we look at where the employment gains have been over the last two years, we can plainly see that employment growth has concentrated in higher wage sectors (Chart 1). At the same time, the sectors with the most job losses are in the lowest wage sectors. This explains why there is such a disparity in the size of the vacancy gap across industries and points to the fact that many workers have been able to move up the wage curve by changing industries (Chart 2).

For businesses that have high vacancy rates (vacancies relative to labour demand) and are offering lower wages, the obvious solution is to increase pay. And we’d note that wages have been rising, but they have not been nearly enough to compete for workers (the average wage gain since the pandemic is 10.3% in high vacancy sectors compared to 8.6% for low vacancy sectors). In order to make the wage rate in these sectors competitive enough to draw workers back, the wage adjustment would need to be several multiples of the current wage growth rate, and that is just not viable.

To fill or to cut

So how does this get remedied? We can’t see firms in low wage sectors boosting wages enough to incentivize workers to come back. And if the lack of skill is really a problem in filling roles, it will take years to retrain the labour force. That leaves one obvious path to close the vacancy gap in Canada – an economic slowdown that cuts down on the number of available job postings. We have already seen a glimpse of this in recent months. With the economy having shed 92 thousand jobs since May, job vacancies (lagged one month) are down by 78 thousand positions as of August. We expect this trend to continue going forward. Just looking at more current readings from the U.S., job vacancies have dropped by 1.1 million positions in August alone (a 10% decline). Given our forecast for the Canadian unemployment rate to rise from 5.2% to 6.5% in 2023, this would imply that the vacancy rate should fall from 5.4% currently, to the 3% to 4% range. This will ease wage pressures and better enable the BoC to achieve its goal of bringing down inflation. Though we recognize that cutting job openings is less favourable to filling those jobs, it appears to be the most likely solution to fixing the vacancy gap in Canada.

Footnotes

- Note #1: Variable Construction

Vacancy measures (Vacancies, Payroll Employees) needed to be reconstructed to ensure consistency when comparing across sectors or time. There were six reconstructed sectors that were built by summing the sub-sector values, and vacancy rates were calculated using the newly reconstructed values.

Below is a breakdown of the sub-sectors used to construct the final vacancy rates.

Agriculture;

o Crop Production

o Animal Production & Aquaculture

o Support Activ For Agriculture & Forestry

Forestry fishing, mining, oil & gas;

o Forestry & Logging

o Fishing, Hunting & Trapping

o Oil & Gas Extraction

o Mining & Quarrying [Except Oil & Gas]

o Supp Activ For Mining, & Oil & Gas Extraction

Trade;

o Wholesale Trade

o Retail Trade

Finance, insurance, real estate and leasing;

o Finance & Insurance

o Real Estate & Rental & Leasing

Business, building and other support services;

o Management Of Companies & Enterprises

o Canada: Payroll Empl: Admin & Supp, Waste Mgmt & Remed Svc

Information, culture and recreation;

o Information & Cultural Industries

o Arts, Entertainment & Recreation

- Note #2: Seasonally adjusted quarterly vacancy (Vacancies, Payroll Employees, Vacancy Rate) data is used when monthly data is unavailable. Monthly vacancy data used following September 2020.

.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share this: