Federal Housing Plan: Ambition and Reality

Rishi Sondhi, Economist | 416-983-8806

Date Published: April 29, 2024

- Category:

- Canada

- Real Estate

Highlights

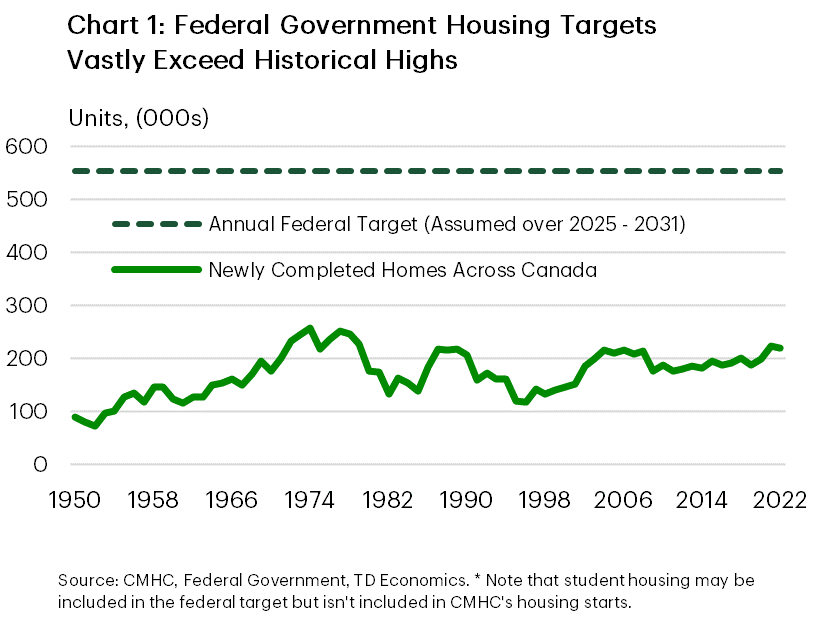

- The federal government’s ambitious housing plan pledges several measures that could impact housing demand, supply, and productivity. The plan envisions 3.87 million new homes by 2031, which implies a record high for homebuilding to be sustained for several years.

- Supply-side measures are perhaps the boldest, but efforts to boost the country’s housing stock are bumping up against challenges such as elevated interest rates and capacity constraints. Meanwhile, demand measures contained in the plan are unlikely to move the needle in a significant manner.

The federal government’s new housing intiative, entitled “Canada’s Housing Plan”, is aimed at addressing the country’s affordability challenge and is also highly ambitious. It includes rolling out measures that industry stakeholders have been desiring for years. The plan targets 3.87 million homes by 2031, which breaks down to 2 million net new homes over and above the 1.87 million that would have been built anyways under CMHC’s forecast.

A few other considerations:

- This 2 million further breaks down into 1.2 million homes through the plan (and through actions taken in fall 2023), with the feds calling for support from other levels of government to build the additional 800k.

- Assuming the target of nearly 4 million homes is counted from 2025-2031, this implies about 550k new units annually. Some of the federal government’s total may reflect a rise in student residences which are not counted in CMHC’s housing starts data. However, that doesn’t significantly change the narrative that the plan would require new housing construction to be sustained at rates well above historical maximums (Chart 1).

- The federal government’s target lags that of CMHC (5.8 million new homes by 2030) by a considerable margin, although the latter’s target is intended to restore affordability to its pristine 2003/04 levels.

Measures in the plan are plentiful, and it’s helpful to break them down into those that could primarily impact demand, supply, and productivity as well as “other” measures. We recognize, however, that any individual policy may influence several of these broad groupings.

Demand Measures Unlikely to Be Game Changers

It could be reasonably argued that governments shouldn’t be stoking demand at a time when affordability is historically stretched. However, proposed measures are unlikely to significantly influence our resale housing forecasts. For instance, the impact of the decision to lengthen amortizations from 25 to 30 years is blunted by the fact that it only applies to first-time homebuyers (FTHBs) who purchase newly completed homes (i.e., a small sliver of the market) and take out an insured mortgage. And the (already announced) extension of the foreign buying ban hits at a time where foreign buying may be 1-2% of activity. However, money for green retrofits should boost renovation spending.

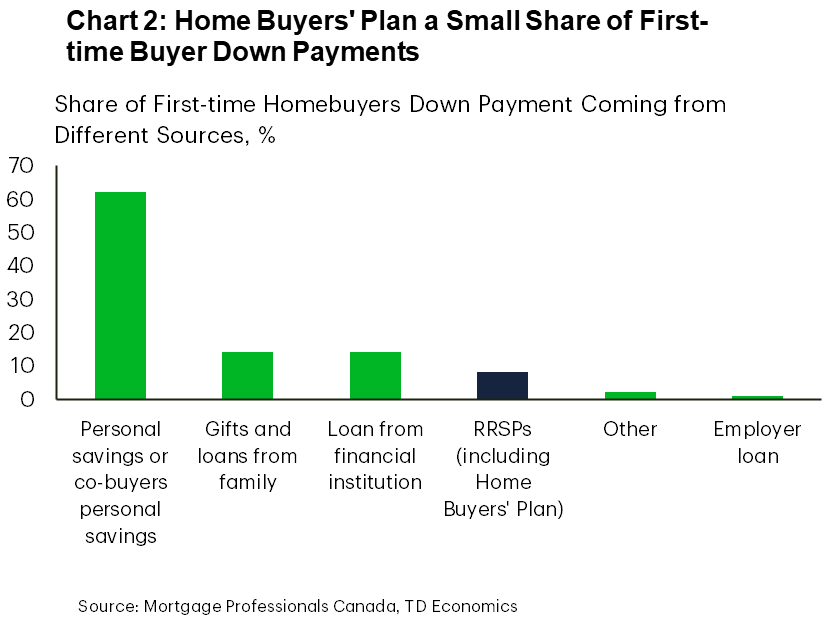

Increasing the Homebuyers Plan withdrawal limit from $35k to $60k should have some impact on households, although it may come through slightly lower household debt levels. Note that survey data points to 30% of FTHB’s withdrawing from their RRSP’s to finance down payments from 2018-20201, but these withdrawals only accounted for 8% of the value of the down payment (Chart 2). The primary source of down payments will likely continue to be other personal savings and parental gifts. Whatever impact does come from this policy will also be lagged a bit, as additional funds put into an RRSP must be in it for at least 90 days before being withdrawn.

The federal government will also restrict purchases of existing single-family homes by large corporations, but data gaps make this a grey area for our analysis. Other types of buyers would likely backfill this demand, presumably to be owner-occupiers, thereby removing rental supply from the market.

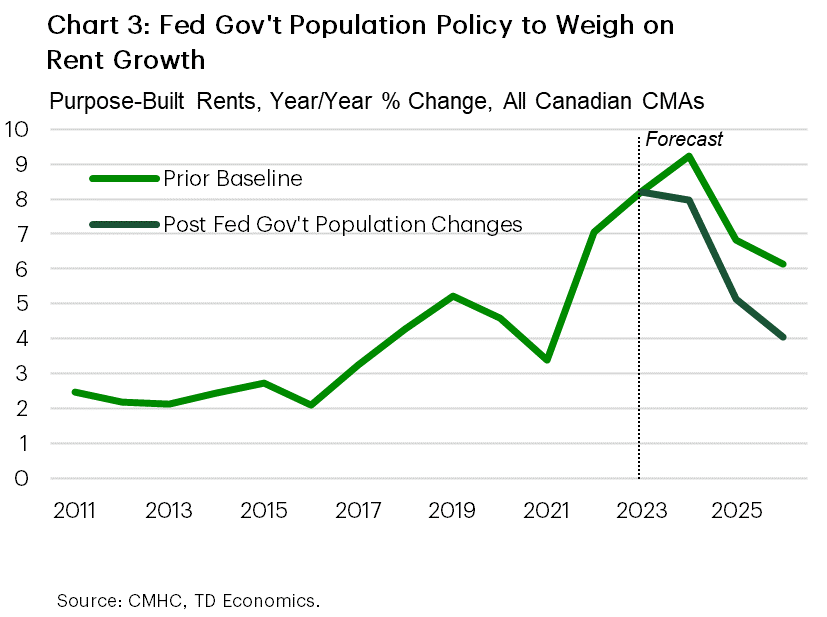

Although we anticipate a modest impact from the federal housing initiative, what will have a considerable impact is the separate federal plan to lower the share of non-permanent residents in Canada’s population from 6.5% to 5% by 2027. If realized, this policy will have a meaningfully negative impact on rent growth (Chart 3), challenging the economics of such projects for investors. This type of demand has been important, with Bank of Canada data showing that 25% of mortgaged home purchases were done by investors in 2023Q3.

Supply Policies to Face Headwinds

Overall, the plan seems likely to bolster CMHC’s measure of housing starts, although achieving 550k new homes each year is an extremely daunting task. Importantly, the eventual lift to new housing completions flowing from these new starts will come several years down the road, with any affordability improvements in the resale market (by far the largest housing market in Canada) not occurring until even further into the future.

Just how much housing starts will increase (and when) is highly uncertain and is facing several headwinds:

- Interest rates are elevated, although we expect the Bank of Canada to be cutting rates by the summer, and bond yields should grind lower through next year.

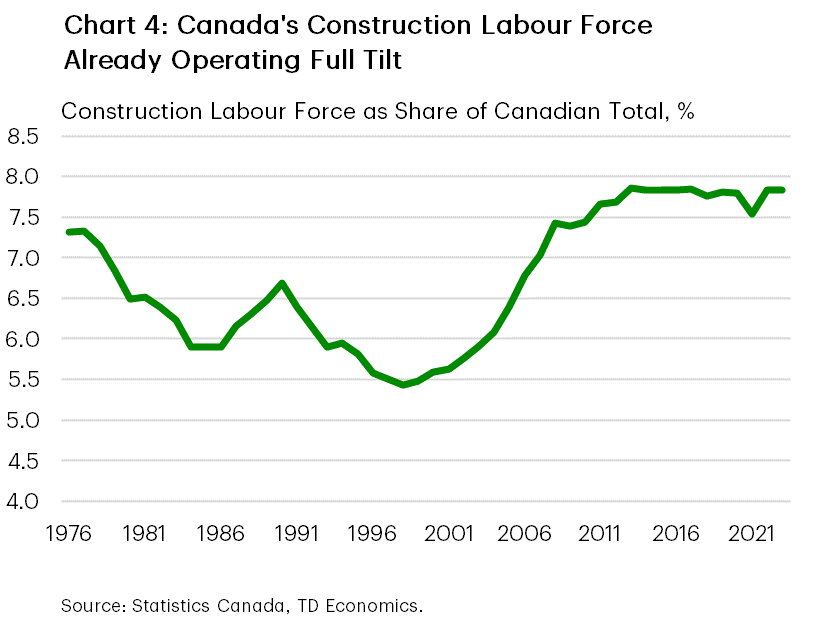

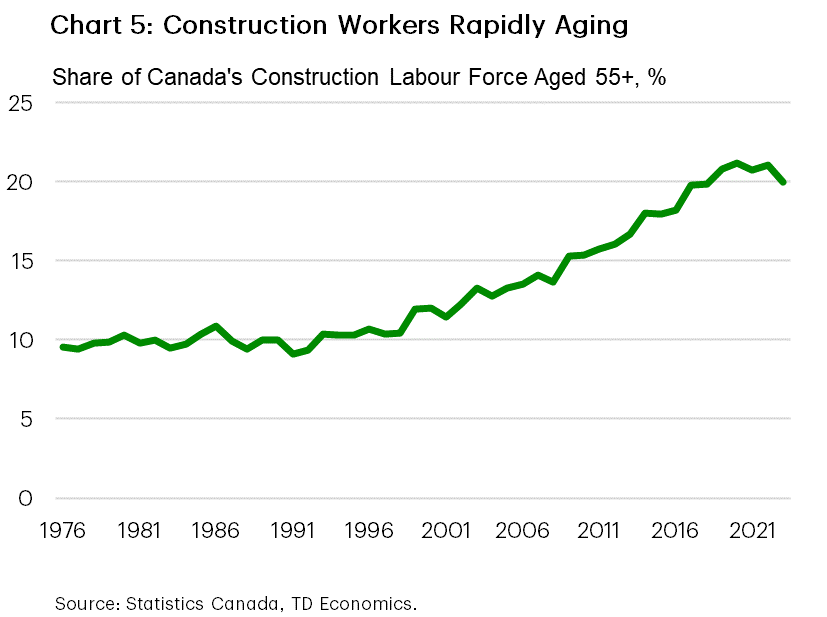

- The industry is already operating at an elevated pace. Housing starts are trending at 242k units, not too far off the all-time high of about 270k units. Homebuilding is facing worker shortages, the workforce appears stretched-thin as is (Chart 4), and residential developers must compete with non-residential projects for tradespeople. For the latter, non-residential capital spending intentions are robust for this year. Tradespeople are also getting older (Chart 5) have earlier retirement ages, and recent newcomers (the driving force behind Canada’s population growth) have gone into construction at a lesser rate than other industries, according to a Bank of Canada analysis2. To their credit, the federal government is attempting to improve the labour shortage situation through new investments in training and credential recognition, alongside new programs aimed at retaining newcomers who work in construction.

- Aspects of the plan depend on other levels of government. For example, most of the $6 billion put towards critical infrastructure is supposed to go to the provinces, the effort towards unlocking surplus public lands requires coordination across governments, and the federal government will modernize the National Building Code, but can’t force the provinces to adopt it, as they have their own. Several provinces have already raised alarm bells over the plan.

Whatever the boost to housing starts, considerable focus in the plan has been placed on the country’s purpose-built rental market. The Apartment Construction Loan Program (ACLP), which provides low-cost loans for purpose-built projects, has been topped up by $15 billion and will be made easier to access by builders. Meanwhile, provinces and territories who have their own ambitious housing plans will be given access. The ACLP is expected to generate an additional 30k rental units and could also become more useful to builders in an environment where borrowing conditions are tough. The feds will also be increasing the accelerated capital cost allowance from 4% to 10% for rental units, improving the after tax-return from these projects. The Housing Accelerator Fund (seemingly popular with municipalities) will also be topped up, although this may not result in purpose-built rental construction exclusively. Although not creating new rental units, measures will be implemented on short-term rentals to return rental stock to the long-term market, and a fund will be created that non-profits can use to keep rental housing affordable.

Several measures won’t show up in the housing starts data that we forecast but will nonetheless raise the overall housing stock. For example, student housing will receive a boost from the federal pledge to remove the GST on the construction of these types of units, low-cost loans for secondary suites will be provided, and money will be earmarked for towards housing for vulnerable populations.

The Affordable Housing Fund will also be topped up by $1 billion and be made easier to access, while investments will be made in Indigenous housing and a new co-operative housing development program. The feds will also tie transit funding to housing requirements starting in 2026, offering a solid incentive to make the necessary regulatory changes to boost construction near transit.

Measures that Could Potentially Enhance Productivity

The government will roll out its standardized housing catalogue, plans on implementing an industrial homebuilding strategy through stakeholder consultations, will invest in innovation and new approaches to homebuilding (i.e., mass timber, modular construction), will modernize the National Building Code, and help municipalities streamline approvals. Very interestingly, the government will also offer low-cost loans for prefabricated housing projects.

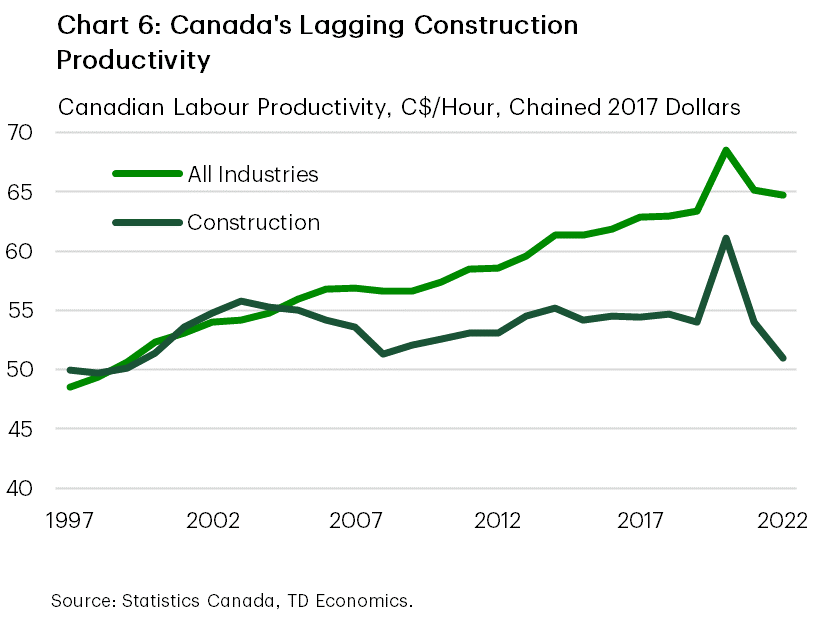

Industry stakeholders have been touting several of these measures, and they could help boost productivity in an industry where it’s been sorely lacking. For example, over the last 10 years labour productivity in Canada averaged 1% growth, whereas construction productivity declined slightly, on average (Chart 6).

Other Measures

The federal government will also roll out several measures meant to support renters and will attempt to crackdown on mortgage and other real estate fraud. Notably, through changes to the Canadian Mortgage Charter, the government plans on making permanent some instances where amortization lengths for borrowers were temporarily extended. Such a move could potentially reduce the interest rate sensitivity of these borrowers.

Thoughts on the Increased Capital Gains Inclusion Rate

Although not part of the Canada Housing Plan, the planned increase in the capital gains inclusion rate on June 25th of this year should have some impact on both demand and supply. The policy change will result in more tax being paid on secondary properties like investments and cottages. The tax will also hit at a time when the federal government also aims to slow population growth, leaving investment properties impacted by two factors and potentially weighing on rental supply. In the resale market, the tax could cause some sellers to list their properties ahead of its deadline which, on the margin, could add some near-term downward pressure to prices.

Bottom Line

The federal government’s housing plan is highly ambitious and should deliver at least some boost to housing supply, particularly in the purpose-built rental space. However, capacity constraints in the construction sector will limit the government’s ability to reach its lofty target for new homes. The coming years should provide an important litmus test for how well policies geared towards purpose-built housing can support rental construction. This is because population growth is expected to be much slower due to the federal government’s plan to lower non-permanent resident levels.

Demand-side measures in the plan are unlikely to deliver game-changing market impacts. However, overall construction productivity could be enhanced through the plan. This would be good news for an industry where productivity has lagged for many years.

End Notes

- Dunning, W. (2021). Annual State of the Residential Housing Market in Canada. Mortgage Professionals Canada. https://mortgageproscan.ca/news-publications/publications/consumer-reports

- Champagne, J et all. (December 2023). Assessing the Effects of Higher Immigration on the Canadian economy and inflation. Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/san2023-17.pdf

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: