Canadian Federal Housing Plan: The 500k Marathon

Rishi Sondhi, Economist | 416-983-8806

Date Published: June 3, 2025

- Category:

- Canada

- Real Estate

Highlights

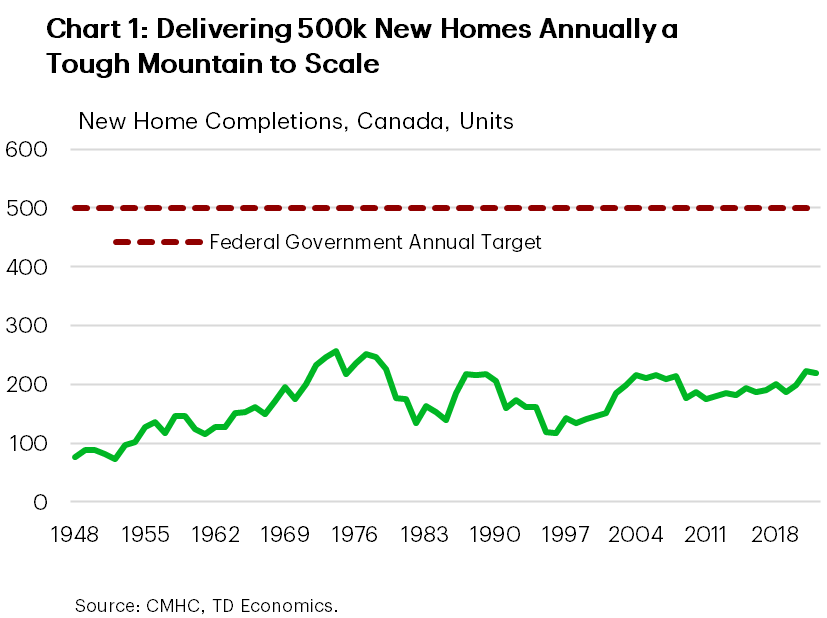

- The newly elected Carney government has set a goal to ramp up the level of Canadian housing completions to 500k per year, over the next 10 years, to restore affordability. The previous high was 260k, reached in the mid 1970s.

- Through its housing plan, the federal government would boost new supply through several measures, including cutting the GST on new homes, lowering development charges, and making favourable changes around tax incentives for purpose-built rental construction. These measures are likely to fall well short of closing the gap between what is currently completed and what the government is targeting.

- However, bringing annual completions to 500k may not be necessary to restore affordability to more reasonable levels. Our analysis suggests that 400k may do the trick. Granted, that’s still a tall order.

- To hit the 400k level, the government will likely have to rely on a combination of workforce growth (which is challenged by the wave of retirements set to impact the construction industry in coming years), and an unprecedented boost in productivity. The latter would likely require a revolution in how new housing is delivered.

- Productivity could be enhanced through the government’s “Build Canada Homes” plan, especially, it’s focus on growth Canada’s prefabricated construction industry. While international experience does offer hope, scaling up Canada’s prefabricated sector has challenges of its own.

Addressing housing affordability is a central plank of the new Liberal Government. PM Carney has pledged to increase housing supply to 500k units each year. This is a lofty task indeed, as the high-water mark for completions in Canada is 260k, reached in 19741 (Chart 1). Imbedded in the federal housing plan are several ideas to stimulate the delivery of new supply. What are these measures and how likely are they to bring the federal government to its stated goal?

- Cutting the GST on new (or substantially renovated) homes for first-time homebuyers: This policy would likely offer an initial shot-in-the-arm to affordability. However, the resulting lift to demand would probably leave prices higher than they otherwise would have been in relatively short-order, eroding the benefit of the policy, and making its impact on demand short-lived. Moreover, it’s impact will be limited by its targeted nature. Nonetheless, the short-term increase in demand should translate into more supply.

- Reducing development charges by 50%: If this policy is indeed implemented, it could bear fruit in markets like Vancouver and, especially, Toronto, where these charges are relatively elevated.

- MURB: The federal government plans on reviving the MURB tax program. The Multiple Unit Residential Building (MURB) program offered investors in rental apartments the ability to deduct expenses from their income, for tax purposes. It ran from 1974 to 1982 and lifted construction of purpose-built rental units by 195k units over that time (about 25k per year), according to the federal government.

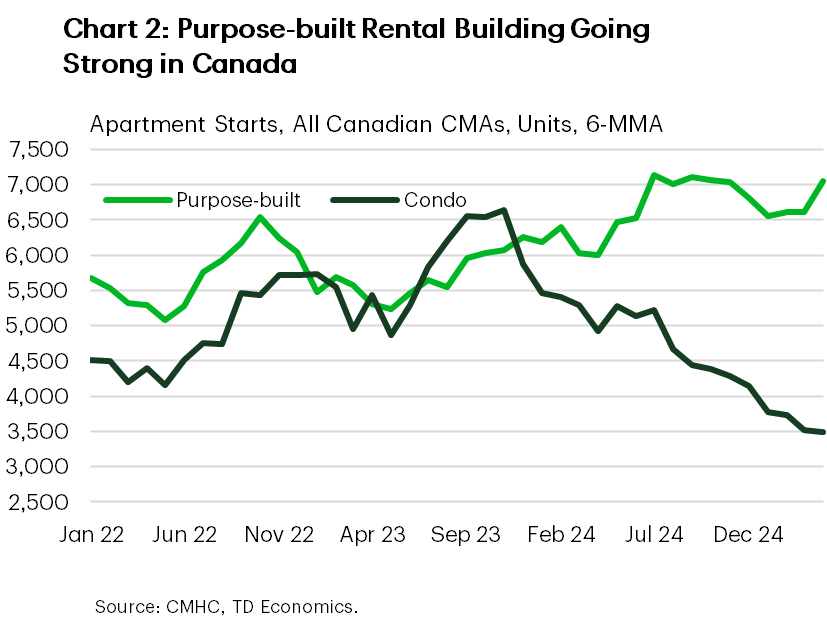

- Would this program be as successful this time around? We should begin by noting that the federal regulatory backdrop is already quite favourable for the supply-side of purpose-built rental construction given policy changes like, for example, cutting the GST on these structures. And there is a significant amount of purpose-built rental apartment units under construction while starts have been holding up well (Chart 2).

- The MURB will allow individual investors to book depreciation on their personal income taxes, thereby lowering their tax bill and enhancing supply-side incentives for more investment in the purpose-built space. However, requiring a level-shift upwards in rental construction from its currently elevated rate requires demand to do its part. This could be a dicey proposition over the near-term given factors such as declining rents.

- After short-run headwinds dissipate, we could see the MURB offering a nice lift to purpose-built rental construction. Would it be the same boost we saw when it was first implemented? There are a few obstacles standing in the way, including the fact that construction time-lengths for apartment buildings have risen dramatically over time. In addition, competition for real estate investment dollars has become fiercer, as purpose-built rental units are not the only game in town for those want to invest in residential real estate, as was mostly the case back then.

All told, these measures could lift housing starts by some 15k – 20k units above our baseline. However, the impact could be more apparent over the medium term. In the short-run, homebuilding will be challenged by a myriad of factors including elevated construction costs, economic uncertainty, rapidly slowing population growth, oversupply in the GTA condo market, and past declines in home sales. Accordingly, we see the level of Canadian housing starts dropping from 245k units last year to about 215k by 2026.

The government’s plan will also incentivize the conversion of existing structures into affordable housing units by reducing the tax liability for owners who sell their units if the proceeds are reinvested back in purpose-built rental housing. It will also reduce red tape by (for example), fast tracking approvals, and leveraging pre-approved, standardized housing designs across the country. These initiatives are difficult to model and could drive homebuilding to exceed what we’ve estimated for the other measures.

Taking Issue with 500k

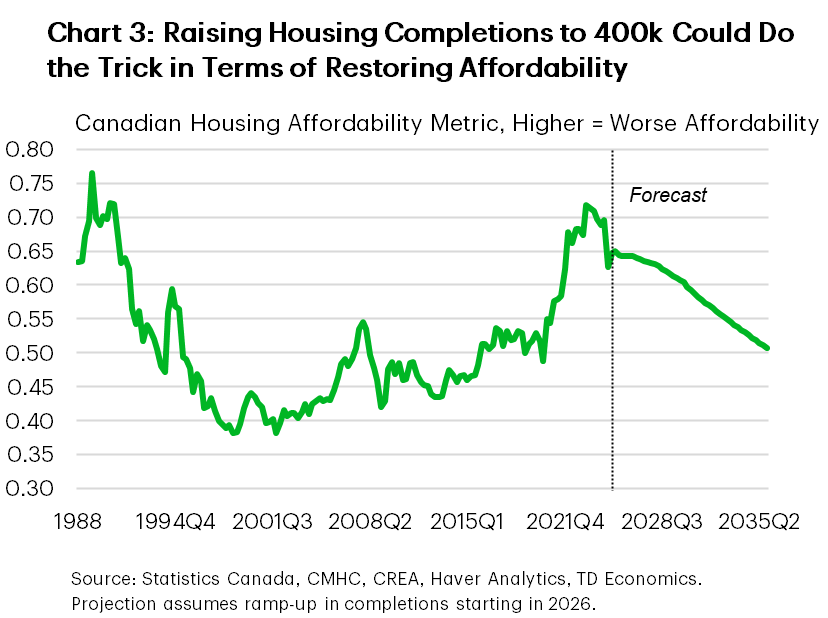

Policies reviewed so far are likely to fall well short of closing the gap between the roughly 210k completions that Canada averages yearly, and the federal government’s goal of getting to 500k units delivered over the next decade. However, is 500k even the “right” number to be aiming for? It’s perhaps workable as an aspirational target, but our modelling suggests that if Canada were to achieve annual completions of 400k (Chart 3), then housing affordability might return to its pre-pandemic level. This assumes that Canada stays clear of a major recession, which would be a painful way to quickly improve affordability.

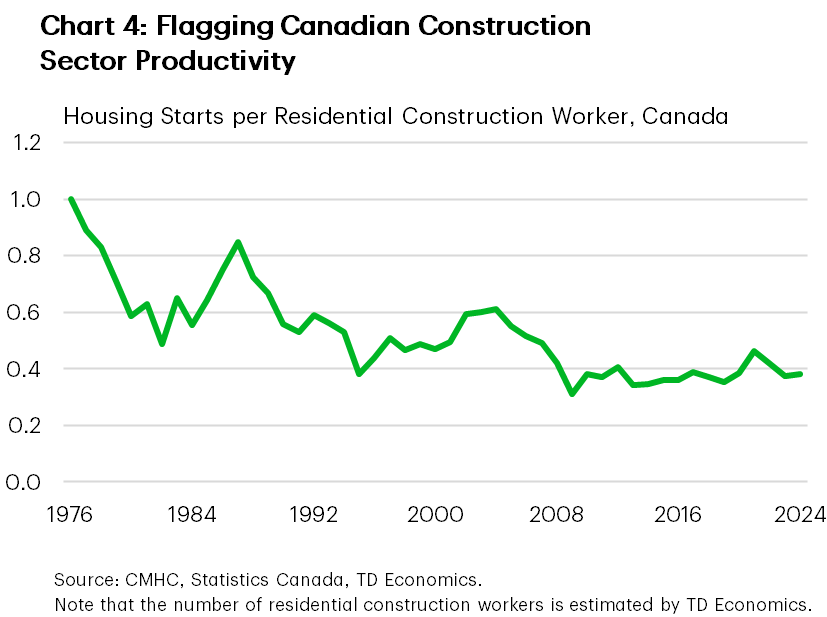

That’s less of a mountain to scale, but it’s still quite formidable given industry constraints. Namely, productivity in the construction industry has been an issue (Chart 4), and construction, like other segments, will be facing a wave of retirements in the coming years. In fact, industry estimates project a 108k shortage in Canada’s construction industry by 20342 after accounting for workforce needs and retirements.

At current productivity levels, getting to 400k completions per year in 10 years would require Canada’s residential construction workforce to expand by 16% each year (Table 1). This is untenable, especially given retirements and that the share of Canadian employment concentrated in construction is already elevated. Also, the federal and provincial governments have ambitious goals in infrastructure building, and these projects will compete for tradespeople.

More realistically, Canada could hope for a combination of a rising construction workforce and an increase in productivity. As a simple illustration, let’s assume a steady gain in the residential construction labour force of 1% per year (somewhat below the 10-year average), productivity would have to rise 50% from current levels to hit 400k units in 10 years. This brings us to the discussion of the federal government’s plan to create a new housing entity called “Build Canada Homes” (BCH). To hit it’s housing target, the BCH initiative will have to play a key role.

Hitting 400k Housing Completions / Year

| Workers | Productivity Assumption | Annual Workforce Growth Required Over 10 Year Period |

| 1,110,032 | Current Level | 16.3% |

| 860,649 | Long-term Average | 2.6% |

| 449,551 | Max Level | -3.4% |

| 750,022 | 50% Increase From Current Level | 1.0% |

Prefab a Panacea?

Boosting construction sector productivity by an unprecedented amount will require a revolution in the way housing is delivered. And indeed, central to BCH is the government’s desire to kickstart Canada’s prefabricated construction industry3 by providing nearly $40 billion in financing. Though industry estimates suggest that modular housing currently represents only 4-6% of housing construction in Canada4 research has highlighted the potential for the prefabricated housing process to speed up construction timelines by 50% and cut costs by 20%5.

Jurisdictions like Japan and Sweden have well developed prefabricated industries, accounting for about 15% of the housing stock in the former and upwards of 45% in the latter6. In Sweden, the prefabricated construction sector was built-up in response to several challenges including labour availability, an energy crisis, a supply shortage, and a harsh climate7. In Japan, its industry needed to evolve in response to the monumental task of rehousing its urbanizing population after the devastating impacts of World War II. The Japanese government played a long-lasting and central role during the prefabricated industry’s formative years, including through the establishment of a housing-focused entity that delivered low-cost loans to stimulate housing supply. Notably, consumer resistance was an important barrier in Japan, which had to be overcome through methods such as special government incentives8.

One can draw parallels between the federal government’s plan and Japan’s experience, but Canada’s prefabricated sector does face obstacles including higher transportation costs during construction. Some re-thinking around the financing and inspection portions of the homebuilding process could also be required. And of course, there are limits around the uniqueness of factory-made housing. Perhaps more substantively, a significant, stable source of demand is required if the industry is to scale up, and the federal government’s pledge to purchase bulk orders from manufacturers is a step in the right direction. However, if international experience is a guide, these will have to be sustained efforts. Also, prefabricated housing works best when the same design is repeated many times, but design guidelines can vary across provinces and municipalities (of which, there are over 5k in Canada). This could offer a significant challenge to the industry’s ability to scale-up. That said, the federal government’s housing catalogue (designed by local architecture and engineering teams) could help in this respect.

Importantly, the mix of housing being delivered matters are great deal. The BCH would allocate about $10 billion in low-cost financing for affordable builders. It remains to be seen if this can make a significant mark on affordable housing in Canada. After all, research has shown that costlier plans to tackle shortages of deeply affordable housing in Canada have fallen short.9

Bottom Line

Construction sector productivity and a retiring workforce are structural challenges that will need to be overcome if the government wants to hit its 10-year target of 500k new homes each year. However, this level probably isn’t required, as a 400k run rate should be enough to restore affordability over time.

Most parts of the Liberal plan should add to the nation’s housing supply, but not enough to hit the half-million target. The federal government will likely be leaning in Canada’s prefabricated housing industry to do the trick. Prefabricated housing can lift productivity. However, the industry is currently small, and scaling up will require a sustained effort on the part of the federal government, if international experience is a guide. Housing design codes that vary substantially across regions present another challenge for factory-made housing’s ability to scale up.

End Notes

- It’s likely this level was exceeded in 2024, but CMHC stopped collecting Canada-wide completions data in 2022. We have data at the CMA level however, and there were robust gains in 2023 and 2024.

- Buildforce Canada. (2025). Canada Construction & Maintenance Looking Forward – Highlights 2025-2034. https://www.buildforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2025-Canada-Const-Maint-Looking-Forward.pdf

- Prefabricated housing pertains to homes (or components of homes) that are constructed offsite in a factory setting and then transported and assembled on the final location.

- Hassan, S. (2025, May 15). In Canada’s housing crisis, are modular homes a cheaper and faster solution? CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/modular-homes-housing-crisis-1.7535799

- Bertram, N., Fuchs, S., Mischke, J., Palter, R., Strube, G., Woetzel, J. (2019). Modular construction: From projects to products. Mckinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/modular-construction-from-projects-to-products

- Ibid

- Terner Center for Housing Innovation – U.C. Berkley. (2017). Housing in Sweden: An Overview. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Swedish_Housing_System_Memo.pdf

- McKellar, J. (1985). Industrialized Housing: The Japanese Experience. Centre for Real Estate Development, MIT. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/schl-cmhc/nh15/NH15-655-1985-eng.pdf

- Whitzman, C. (October 2024). Homeward Bound: How to Create Deeply Affordable Housing. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Homeward-Bound-How-to-Create-Deeply-Affordable-Housing.pdf

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: