Highlights

- Canada's aging population will challenge firms' ability to maintain their workforce.

- This slow-moving train has been underway for many years, but the willingness and ability for workers to extend their careers has provided an important buffer.

- Purely by the numbers, rising immigration and greater participation rates fill the retirement gap. But it doesn’t necessarily fully solve for the matching and integration of people desired by businesses.

The aging of Canada's population will be a dominant force in defining the future path of the economy. With each passing year, this slow-moving train intensifies, promising to leave a massive mark on consumer spending patterns, government health care costs, and housing development. But the most acute effect of people leaving their prime earning years and entering retirement will no doubt be on the availability of workers and any resulting skills mismatch to the needs of employers.

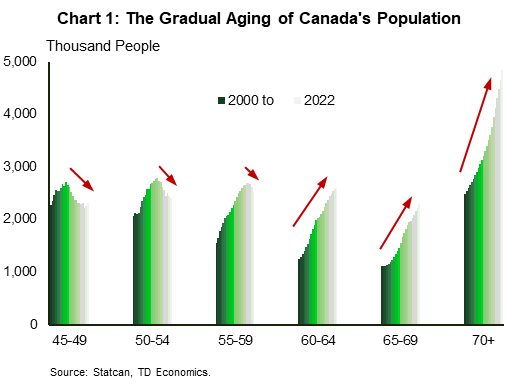

To be sure, this is already playing out with the boomer generation ranging in age between 58 and 77 years (Chart 1). Our calculations show that this so-called greying effect is likely to accelerate over the next several years, posing a challenge for businesses that must hire and train new workers to take the seats of those who leave. Although high immigration targets will support the ability for the prime working age population (25- to 54-year-olds) to offset the wave of retirees, ensuring that Canada's labour supply has the skills needed to fill the jobs demanded by businesses will be a defining challenge for the economy.

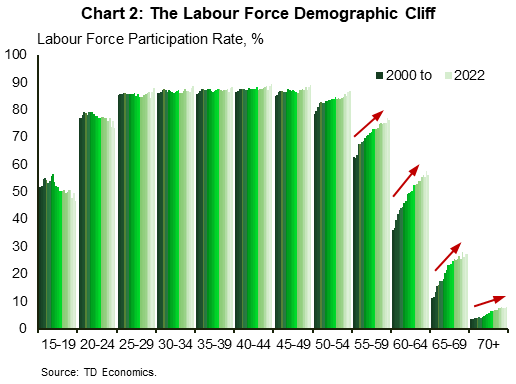

Luckily for Canada, forces at play in recent years have dampened the impact on labour market participation resulting from this grey wave. As we show in Chart 2, there has been a notable increase in the percentage of people remaining in the labour force in each age cohort from 55 and older. This increase in labour market engagement is likely due to several factors. These include the elimination of the mandatory retirement age in various provinces, the ability to defer Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) benefits, the increase in service sector jobs, and the fact that people are generally healthier today than prior generations of the same age.

More recently, the onset of the pandemic appears to have further boosted labour market participation of the mid-50s and early-60s cohorts. This phenomenon may persist if rising rent and housing costs fuel worries about the adequacy of retirement savings. The decline in financial market assets has also likely put a dent in retirement nest eggs. According to a recent Ipsos study, a third of people planning to retire think they will outlive their savings within 10 years.1 Furthermore, only half of people surveyed have a financial plan for retirement. Given the rise in the cost of living and volatility in financial markets, there may be both near-term cyclical and longer-term structural reasons for the trend increase in the labour force participation of older age cohorts.

For employers, this means that there have been fewer retirement parties than would have otherwise been the case. The number of people choosing to retire from 2000 to 2020 has significantly lagged the increase in people entering retirement age. By our calculations, the willingness of Canadian's 60 and older to remain in the workforce has resulted in nearly 1.1 million more workers than what would have been the case if participation rates of the early 2000s were kept constant. This runs contrary to what we are seeing stateside, where it is estimated that the pandemic alone has resulted in nearly 3 million excess retirements.2 For a Canadian economy that still has approximately a million unfilled job vacancies, avoiding a U.S. style retirement boom has been an important buffer for the economy.

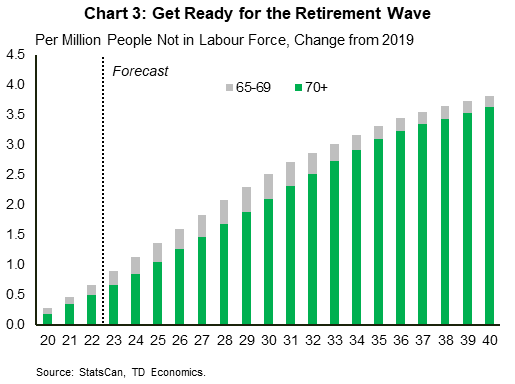

If 2022 was any indication, we might be starting to see the pace of retirements accelerate. The Labour Force Survey estimates that 266 thousand people retired in the prior 12 months as of December, representing a 17% increase over the prior two years. We believe this trend is likely to continue. By 2025, we expect to see the number of people 65 and older grow by 1 million. Based on current participation rates, that means nearly 900 thousand workers will leave their jobs in the next three years (Chart 3). That is a 50% increase in the average number of retirees each year compared to the average of the last 10 years.

This challenge should not be overlooked by any Canadian firm. Though potential retirees may continue to extend their careers and edge up participation rates further, that can only slow and not offset the reality of more and more workers moving into older age cohorts where participation rates decline sharply.

Policymakers have been in tune with this influence. High and rising immigration flows are intended to counterbalance much of this gap. Federal immigration targets aim to bring in roughly 1.5 million permanent residents over the next three years. Of this, 849 thousand – nearly equal to the expected retirees - are economic immigrants. With most in their prime working age, this should be enough to fill the gap due to retiring workers. On top of this, Canada has the right policy in place to facilitate more women into the workplace. With the $10 a day childcare program coming into full implementation, the cost savings to households may start changing incentives for women (and men) to enter the labour market. Looking at the difference in participation rates amongst women in Quebec – which implemented its daycare program in 1997 – a similar outcome could result in approximately 300 thousand more women participating in the labour market.

Problem solved on the upcoming retirement wave, right? Nope. The hard part remains.

Companies are increasingly voicing difficultly in finding employees with the right skills. With so many older workers having to be replaced by younger ones, firms could face a deficit in experience and institutional knowledge. Both employees and employers will be navigating a learning curve.

A higher share of the new-to-Canada workforce tends to have a higher education level than the domestic population, but that might be a signal of skills mismatch to where people will be retiring, versus those coming into the labour market. This exercise is even more complex, considering there are many different points of intersection needed in training, education and industry experience. For instance, some sectors with current high excess vacancy rates are in food, accommodation, manufacturing, and construction. Effective job-to-skills matching is needed to help new Canadians better integrate into the workforce and into society.3

The time has come to not tiptoe on breaking barriers across all areas of the labour market. Recognizing foreign credentials and experience is crucial to the "seamless" integration of new Canadians into the job market. The aging of Canada's existing population is opening the door to make the structural changes necessary to bring in, integrate, and support all current and future Canadians. Therein lies a huge opportunity for Canada.

End Notes

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: