Setting the Record Straight on Canada-U.S. Trade

Marc Ercolao, Economist | 416-983-0686

Andrew Foran, Economist | 416-350-8927

Date Published: January 21, 2025

- Category:

- Canada

- Financial Markets

- Trade

To view the infographic, visit the following link.

Highlights

- Canada is the largest export market for the U.S. and makes up one of the smallest trade deficits, owing largely to U.S. demand for energy-related products.

- Trade in the auto sector is balanced between the 2 nations. While President Trump has mused that the U.S. could replace Canadian auto exports with its own domestic supply, the highly integrated North American supply chains is a major complicating factor.

- Flipping this argument on its head, Canadian auto manufacturing has room to expand. Canada produces only 14 car models but consumes 325 models. The U.S. produces 121 models of the 328 models consumed by Americans.

- With respect to Trump’s assertion that the U.S. subsidizes Canada to the tune of US$200 billion per year, it’s unclear where this number is derived. In any event, rather than a subsidy, the U.S. trade deficit is a by-product of U.S. economic outperformance relative to other countries.

As Canadian’s brace for a long period of “deal making” under President Trump’s tariff strategy, here’s a primer on what’s at stake and the facts behind the rhetoric.

In addition to border security concerns, Trump has argued that “the United States can no longer suffer the massive trade deficits that Canada needs to stay afloat,” claiming that the U.S. subsidizes Canada to the tune of US$200 billion annually. How “massive” is the deficit and is there validity to this claim of subsidization?

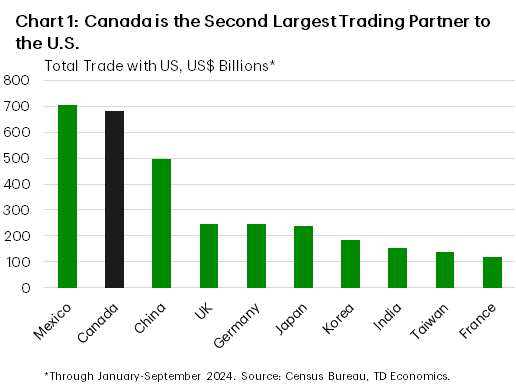

Canada is America’s second largest trading partner, but number one export market

In the first three quarters of 2024, roughly C$800 billion or (US$600 billion) of goods crossed the Canada-U.S. border. Including trade in services boosts these totals to C$910 (US$683 billion).

- That is the equivalent to C$3.6 billion in total import and export flows each and every day.

- Only Mexico edges out Canada (Chart 1).

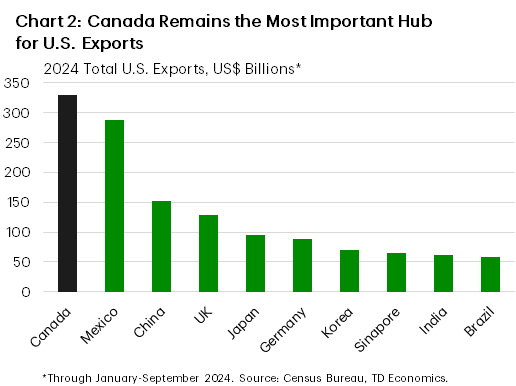

- But when it comes to which country dominates in buying American products, Canada is the single largest market by a large margin with nearly US$350 billion goods and services crossing Canada’s border over the first three quarters of 2024. (Chart 2). Some 34 U.S. states sell more goods to Canada than any other foreign economy.

- Trade between the U.S. and Canada is highly integrated. Most Canadian exports are inputs used by American businesses in their own production – more so than with other trading partners1. Thus, a disproportionate share of the negative tariff impacts on imports from Canada would be through the channel of business supply chains and productivity that would drive higher costs and inflationary pressures at the retail level.

From the American lens, trade with Canada is balanced

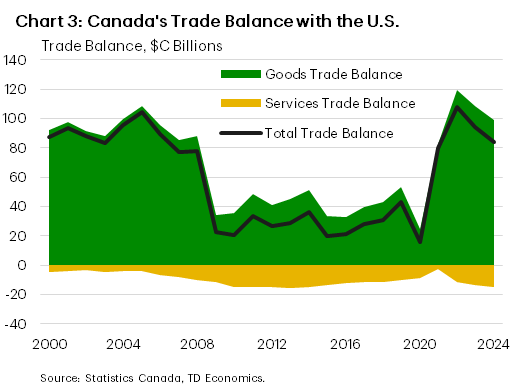

- Based on Statistics Canada data, Canada’s merchandise trade surplus with the U.S. last year was on track to reach C$100 billion. That equates to 3.2% of Canadian GDP.

- The U.S., however, enjoys an edge in services trade, mainly related to Canadians flowing over the American border. This impact shrinks the trade surplus to C$85 billion, or 2.8% of Canadian GDP (Chart 3).

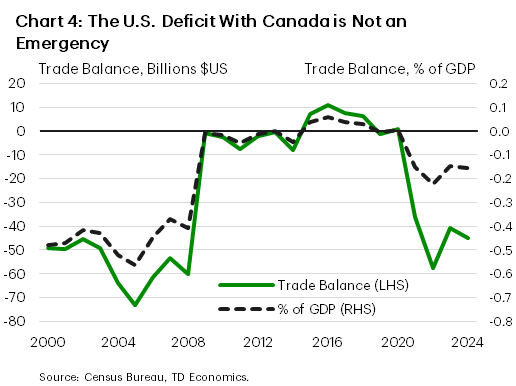

- Looking at the trade situation from the U.S. lens yields smaller figures, partly reflecting different data measurement. Applying Census Bureau figures, the U.S. is on track to record a trade deficit with Canada of roughly US$45 billion in 2024 (or a mere -0.2% of U.S. GDP). In Canadian dollars at the spot rate, this would amount to $65 billion.

Since Trump 1.0, the U.S. trade position eroded against Canada

- The U.S. trade deficit with Canada has deteriorated since Trump’s first mandate – a fact that is probably not lost on the President as he presses on using tariffs as a primary international policy tool.

- Indeed, between 2016 and 2020, the U.S. posted a modest annual average surplus with Canada of around US$20 billion.

- Some of this weakening of the U.S. position with Canada reflects the outperformance of the U.S economy since the pandemic, as well as a material increase in Canadian energy exports southward.

- Despite this loss of ground, the U.S. trade shortfall with Canada remains below its record of almost US$75 billion in 2005 (Chart 4).

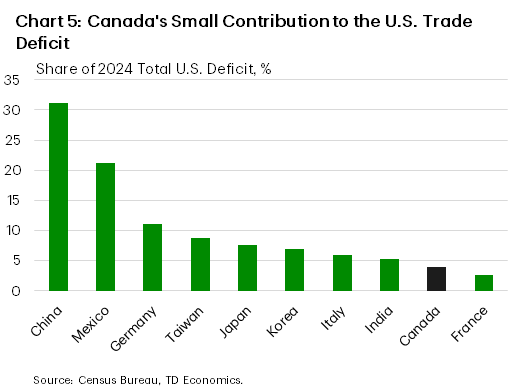

U.S. trade deficit with Canada is the second lowest among trading partners

- Chart 5 shows where Canada stacks up against other major countries.

- The ~US$45 billion shortfall with Canada in 2024 places as the second smallest, behind only France. That amounts to a mere 4% of the overall U.S. trade deficit. So, in essence, reducing imports from Canada would barely move the needle.

- The U.S. trade deficit with Canada was 1/8 the size of China’s and 1/5 that of Mexico.

America Registers a Trade Surplus with Canada in Autos

- A fact that is not well known: the U.S. is a net exporter to Canada of manufacturing goods, particularly motor vehicles and parts.

- The auto sector is the poster child for integrated trade between the two countries as well as Mexico. North American auto parts cross all three borders up to 7 to 8 times prior to final assembly of a vehicle2.

- In terms of final assemblies, Canada supplies around 8 to 9% of what Americans consume annually, while Mexico is closer to 20%, with U.S. production satisfying about 50%.

- Given this high integration, the auto sector would face some of the deepest negative impacts from tariffs.

- By some estimates, average U.S. retail car prices could rise by roughly $3k, though that would depend on retaliation actions by both trading partners. In the event of strong counteractions, severe trade dislocations and significant economic consequences would occur, leading to collapsing demand in all three countries.

Could the U.S. replace Canadian auto supply through higher domestic production?

- The president-elect recently mused: “Canada makes 20% of our cars. We don’t need that. I’d rather make them in Detroit.”

- The statement exaggerates the share of vehicles sold in the U.S. that are produced in Canada by roughly 10 percentage-points. The U.S. could conceivably look to shift this production state-side, but significant near-to-medium term challenges to replacing Canada’s annual exports of around 1.5 million units.

- To fill that gap, the U.S. would need to raise production by more than 10% relative to current levels. Based on the average production capacity of 225k units for existing assembly plants, that would mean roughly 6 new plants would be required. Full-onshoring of all non-U.S. production would require a 75% boost in U.S. production and more than $50 billion in new investment.

This doesn’t factor in onshoring/expanding parts production in the assembly of those vehicles. Failing that, the U.S. would increase its reliance on parts imports.

- This would come at a hefty price tag for U.S. domestic producers, especially in the full-onshoring scenario.

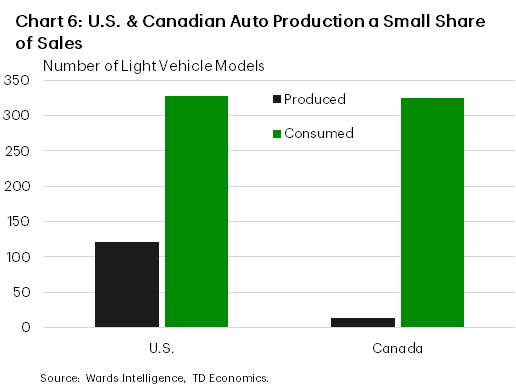

- The other challenge surrounds vehicle choice for American consumers. It’s one thing to boost production volumes. It’s another to provide the diversity of vehicle choice. Consider that in the U.S., there were 328 different vehicle models sold in the U.S. last year, with only 121 of them being produced domestically.

- What if we re-engineer the president-elect’s argument? Could Canada on-shore production to meet its domestic needs and deliver a shot in the arm to manufacturing.

- This would pose an even greater lift in reorienting factories, supply chains and user-choice. Canada currently only produces 14 models of vehicles, while consuming 325 models (Chart 6). Absent a seismic shift in production methods towards efficient, high-variety, low-volume processes, Canadians would likely have to consume materially fewer varieties of vehicles to produce all of its own vehicles.

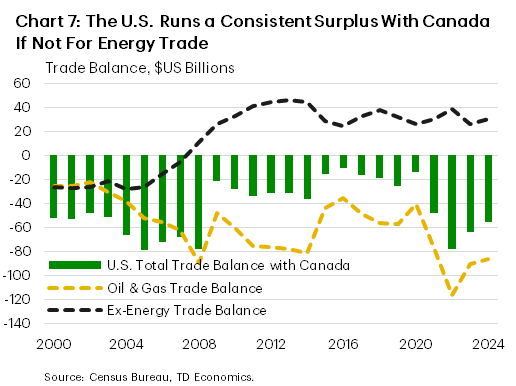

Energy accounts for all of the U.S. trade deficit with Canada

- The trade narrative shifts dramatically when trade flows are decomposed into energy and non-energy components.

- Last year, Canadian exports of energy products (oil, natural gas, power) to the U.S amounted to nearly $170 billion, or almost 1/3 of total shipments. In contrast, energy accounted for only 6% of all U.S. imports. Put simply, Canadian sources are critical to U.S. energy security.

- Remove Canadian energy exports from the equation and the trade story flips. Ex-energy, the U.S. enjoys a trade surplus with Canada of around C$60 (US$45 billion). (Chart 7)

- Canada’s trade advantage in energy has been rising steadily in recent years, most recently on the back of the Transmountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) that, in turn, has sharply boosted Canadian oil exports to the U.S. west coast in addition to Asian markets.

- Canadian crude is a key supplier to U.S. refining, predominantly in the mid-West, with a steadily growing share in the Gulf coast. Since many refineries are built to process Canadian sour, heavy crude, it’s difficult to shift away from that feedstock to alternative sources. This is true even from the U.S.’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which is largely comprised of conventional crude. Countries that could fill the gap are Mexico and Venezuela, but the latter would require lifting sanctions. Given Mexico already enjoys the second largest trade surplus with the U.S., this shift in demand would further widen that chasm, potentially allowing it to overtake China in the pole position.

- If tariffs were extended to Canadian crude oil, it could lead to an immediate jump in U.S. gasoline prices of as much as $0.30-0.70 per gallon. One of the most price-transparent and inflation-sensitive areas for consumers is the movement in gasoline prices.

- Elsewhere, in 2023, Ontario also directly supplied electricity to 1.5 million U.S. homes and is a major exporter of power to Michigan, Minnesota and New York.

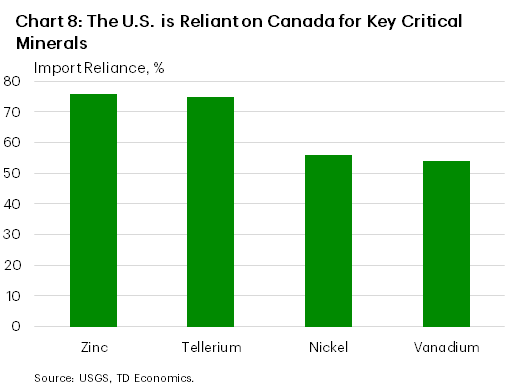

Canada is an Important Supplier of Critical Minerals

- Beyond energy, Canada is also an important supplier of other key commodities, including metals and critical minerals. Notably, on the U.S. government’s 50-item critical mineral list, the U.S. is a net importer of 43 of these minerals.

- While China dominates global production of more than half of the critical minerals outlined by the U.S. government, Canada has been supplying 50–80% of its needs in zinc, tellerium, nickel, and vanadium (Chart 8).

- Outside of this, Canada has abundant reserves of cobalt, graphite, lithium, and rare earth materials that are core to reaching goals on clean energy technologies.

So, what about Trump’s claim that the U.S. is subsidizing Canada by US$200 billion?

- It’s unclear where President Trump or his team derived this number. In a recent press conference, he referred to it while discussing America’s “massive” trade deficit with Canada. Yet, it is roughly 4 to 5 times the officially reported statistics.

- In any event, a trade deficit is not a subsidy. That would ring true, if for example, the U.S. government transferred US$45 billion annually to Canadian companies out of goodwill, but Americans are receiving value for the dollars spent in the form of goods and services. The trade deficit the U.S. runs with Canada reflects their economic outperformance and above-average spending of Americans, that’s driving a hunger for energy products.

- Moreover, the greenback’s reserve currency status also creates massive demand for U.S. financial assets, which in turn allows the U.S. to finance its global consumption at a lower cost.

- It could very well be that President Trump is also factoring in other costs that the U.S. incurs.

- For example, the spending required to bring Canada’s defense spending to 3% of GDP as per Trump’s goal amounts to around US$45 billion.

- But taking into consideration both the deficit and Canada’s military spending shortfalls still leads to a sizeable gap vis-a-vis the $200bn estimate.

- On the other side of the ledger, often overlooked are the net benefits to the U.S. from Canada’s status as a reliable supplier of energy and other goods that are used for both domestic consumption and profitable investment opportunities1.

Bottom Line

Some of the datapoints in this report may come as a surprise to readers. The bulk of the U.S. trade deficit with Canada is owing to energy. Outside of that, the scales tip into America’s favour. Even with this data, it’s proven insufficient to fend off trade attacks that will extend well beyond this current bout. In mid-2026, the USMCA comes under review. Regardless of the deals that will eventually be struck between countries, the lesson that should be learned in Canada is that there can be no guarantee against future tariff attacks.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: