Support Measures Cap 2025 Provincial Budget Season

Marc Ercolao, Economist | 416-983-0686

Rishi Sondhi, Economist | 416-983-8806

Date Published: June 10, 2025

Highlights

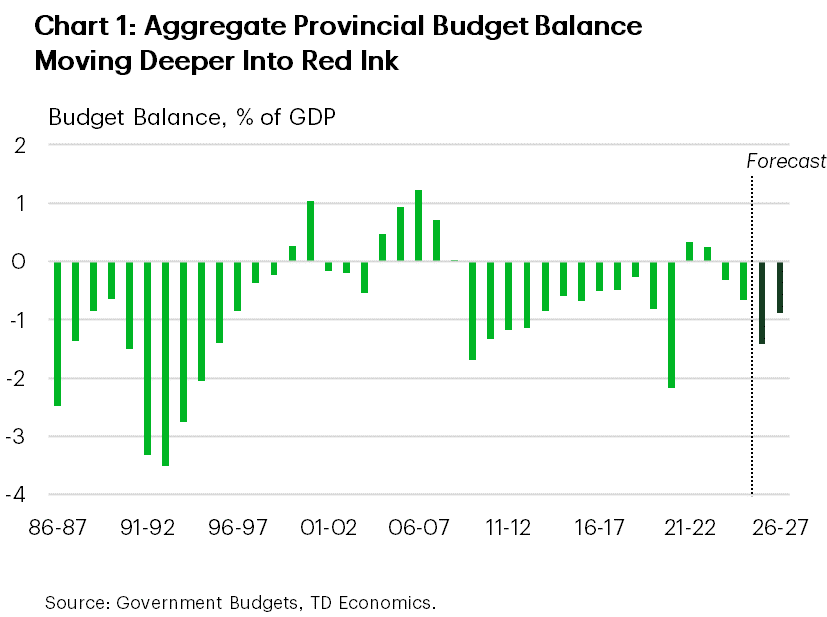

- A weak economic backdrop is expected to drive a 0.7 ppt deterioration in the aggregate provincial budget deficit to 1.4% of GDP this fiscal year - marking the largest bout of red ink in over a decade (outside of the pandemic).

- Nearly every province plans on beefing up their capital spending plans, partly in an attempt to prop up their economies during a turbulent period. Capital spending can also have the beneficial impact of bolstering productivity over the longer run. However, in tandem with deficits, it is also expected to drive provincial debt levels higher, making fiscal situations more vulnerable.

- While provinces allocate funds towards policies that may offer more of a longer-term boost, much of the focus this budget season is on shorter-term measures designed to offset near-term economic softness.

Provincial governments faced the difficult task of tabling their annual budgets amid mounting headwinds from U.S. trade policies. Provincial budget season revealed expectations for weaker economic growth and government revenues across the board, manifesting in provincial bottom lines. Incorporating prudence in budget planning and near-term support measures were key features this budget season. Rising debt burdens are a notable concern, although debt servicing charges are currently manageable.

Budget Balances Worsen Across Provinces

The cumulative provincial FY 2024/25 deficit is forecast to land just north of $20 billion (-0.7% of GDP). From here, a worsening aggregate deficit amounting to $44.9 billion (-1.4% of GDP) is expected in FY 2025/26. This is not threatening compared to the levels seen during the early-mid 90s fiscal crisis period (Chart 1) but does represent the largest shortfall relative to GDP since 2012, outside of the pandemic.

The deterioration is not uniform across provinces, with FY 2025/26 deficits reaching as steep as 2.5% of GDP in the case of B.C. to a balanced bottom line in Saskatchewan. Consistent across most provinces is a worsening revenue growth outlook weighed down by weaker expected economic conditions. After growing by 6% in FY 2024/25, the total revenue take is expected to flatline this fiscal year before rising by a modest 1.7% in FY 2026-27.

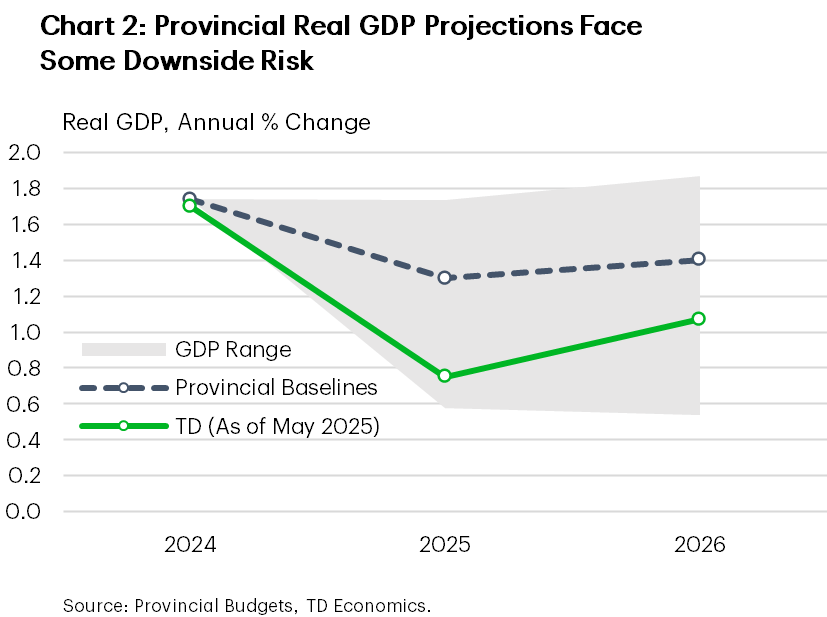

Establishing baseline economic forecasts that underpin fiscal projections were subject to abnormally wide confidence bands. Provincial consensus calls for a moderation in both real and nominal GDP growth in 2025. Some provinces, like Ontario, embedded tariff threats into their baseline forecasts, others opted to exclude them, while some took a middle ground approach. However, several provinces took the prudent step to publish economic scenarios around their baselines to assess potential fiscal impacts.

Chart 2 shows that risks toward real GDP forecasts that were incorporated in provincial budgets are skewed to the downside. Our most up to date real GDP forecast for the Canadian economy over the next two years is tracking towards the lower bound of provincial expectations. Ontario, who was last out the gate to release its budget in May, contains a set of assumptions that probably better reflects the current outlook.

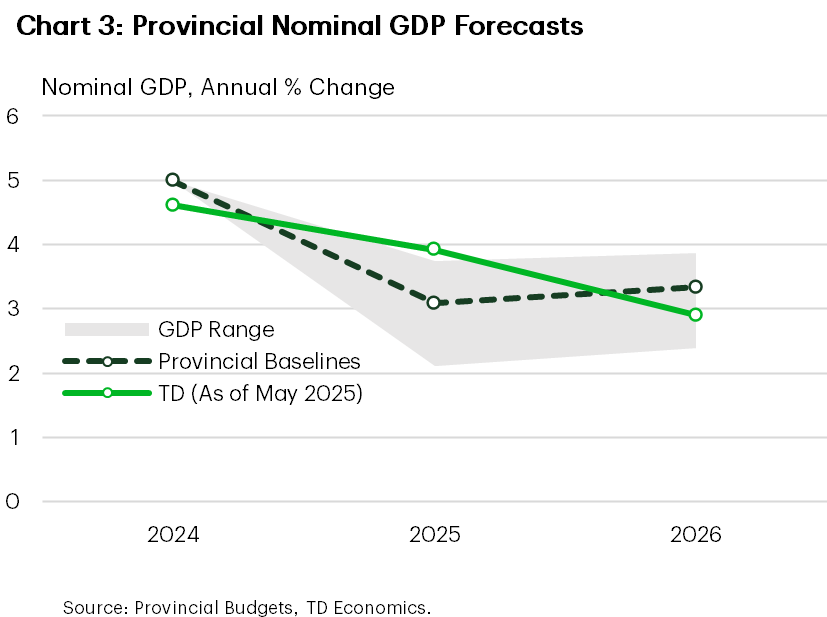

Risks around nominal GDP projections, a better proxy for provincial revenues, are more balanced (Chart 3). Combining the government downside scenarios for nominal GDP growth in Ontario, Quebec, and B.C., revenue sensitivities imply that the combined revenue intake could be ~$2.5 billion lower than in their baseline economic scenarios. However, the current state of play between Canada and the U.S. is significantly less severe than the assumptions underpinning these bearish scenarios. For our part, we have a slightly more bullish nominal GDP forecast than the baseline views of the provinces, stemming from higher inflation forecasts. However, developments since then, including a small downside inflation surprise in April, could cause us to mark down our view for all-items inflation.

One thing to note, commodity producing provinces are facing potential revenue headwinds from recently falling oil prices. At the time of tabling, Alberta and Saskatchewan forecasted WTI prices at $68/bbl and $71/bbl WTI, respectively, for the fiscal year. Newfoundland, which forecasts Brent prices, expected a $73/bbl price. We are still in early days of the fiscal year, but oil prices are averaging $5-7/bbl lower than government projections, introducing revenue downside. In aggregate, this could cost prairie governments north of $4 billion in revenues, though relatively stronger WCS prices could provide some offset.

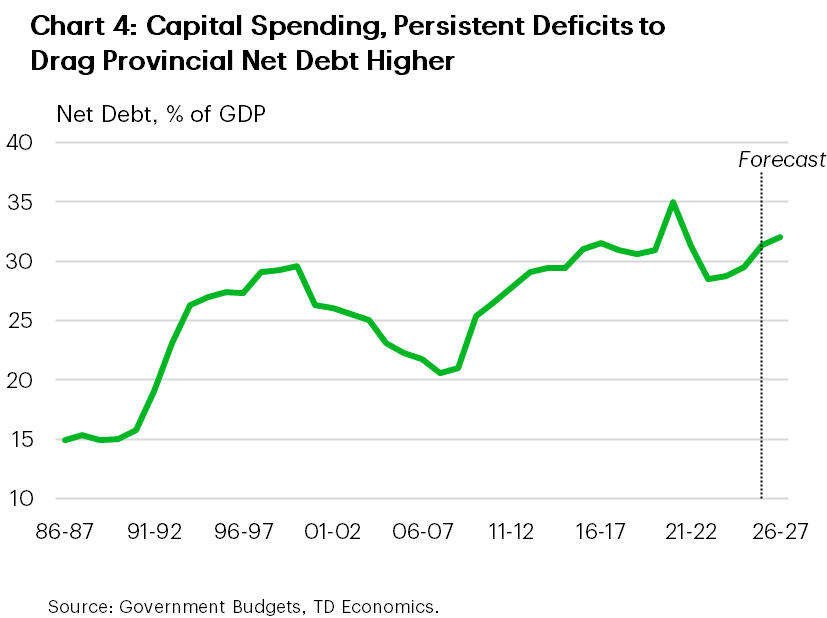

Net Debt is in a More Precarious Position

Based on budget forecasts, cumulative net debt-to-GDP is seen as rising from 29.5% in FY 2024-25 to 31.3% for the upcoming fiscal year. Persistent aggregate deficits and a ramp up in capital spending (more in the next section) will put provincial net debt-to-GDP on a modest upward trajectory. Unlike provincial budget deficits, aggregate debt levels are pushing toward their highest on record, only a few percentage points shy of 2020 pandemic levels (Chart 4). This could heighten fiscal vulnerabilities in the event of a deeper-than-expected economic downturn and risks provincial credit downgrades in the near-to-medium term. Indeed, we’ve already seen Quebec and B.C.’s credit ratings get downgraded in the wake of this budget season.

B.C. is expecting the sharpest increase in its debt burden, poised to rise to almost 35% of GDP over the next three years, more than double its historical average. This would put B.C. in the middle of the provincial pack after a long history of being one of the least indebted provinces. In contrast, Alberta and Newfoundland are expecting a fairly stable debt trajectory over the next three years.

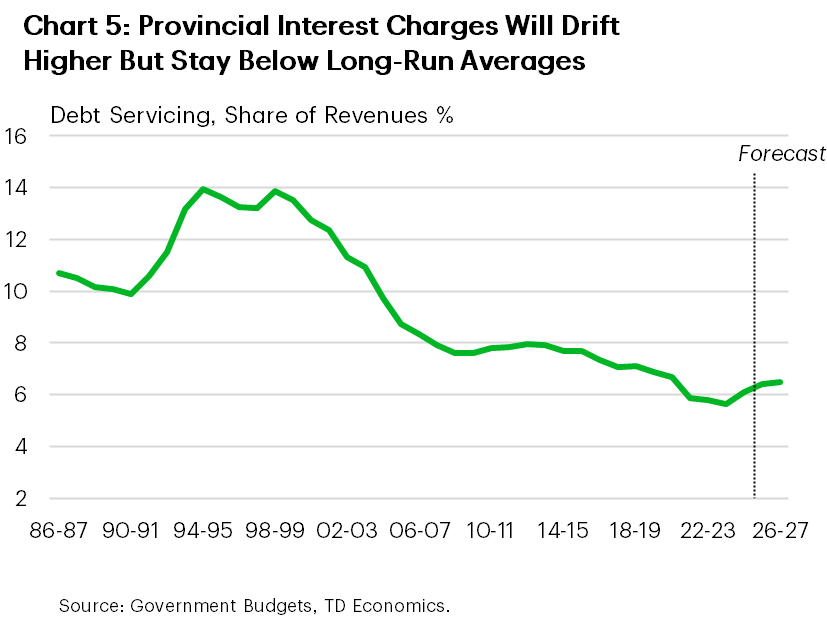

Despite rising debt levels, provinces are expecting to see only a modest increase in their interest burdens. As a share of revenues, provincial aggregate debt servicing is projected to drift slightly higher from 6.1% to 6.4% in FY 2025/26. Near-term downside revenue risks or debt refinancing at higher rates may push this ratio higher, but for now, current debt costs are at low and manageable levels (Chart 5).

Total Spending Moderates, Capital Spending Dominates

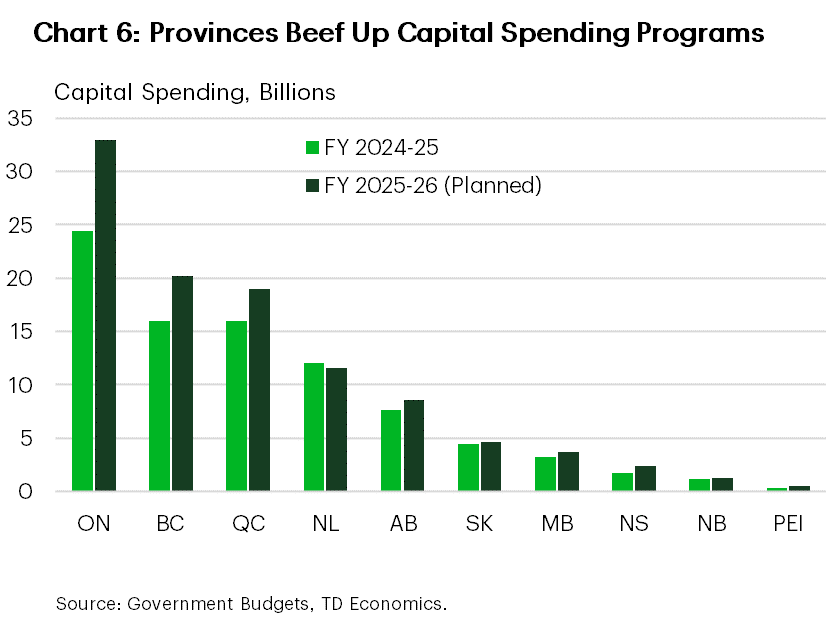

Aggregate provincial program spending growth is slated to cool to 2.8% in FY 2025/26, following a four-year stretch of operational spending growth above 6%. Provinces have instead channeled spending toward large capital programs, mainly focused on health care, education, and transportation infrastructure. In total, planned infrastructure spending in FY 2025/26 will eclipse $100 billion, its highest point on record and up by roughly 20% from last year’s planned level. This exceeds February’s capital intentions survey that pointed to a 6% gain in public sector capital investments this year after massive gains from 2022-2024.

Ontario’s bulky capital plan accounts for a third of total spending, with B.C. and QC making sizeable contributions. Chart 6 highlights the variability across provincial capital programs. All told, this is significant as it could provide a layer of support to provincial economies during a tough time. However, the scale of support will depend on the government’s ability to get these infrastructure dollars flowing. On the flip side, these large capital programs are a core reason for coast-to-coast rising debt loads.

Provinces Adapt a Defensive Tone

Governments are pledging measures that could offer a longer-term boost to their respective economies. For example, the Big 4 provinces are all investing in ways to diversify trade away from the U.S., while Ontario and B.C. will direct attention towards accelerating approval timelines through single window permitting processes. All provinces are prioritizing reducing interprovincial trade barriers. However, given the risky economic backdrop, much of the focus of this budget season is on near-term support measures. This is probably required given that Canada is staring down the barrel of a moderate recession this year.

In terms of near-term measures, Ontario is a prominent example, with $11 billion in temporary support coming through WSIB rebates and a 6-month deferral of provincial tax payments (among other policies). Manitoba is also backstopping economic activity vis-à-vis initiatives amounting to nearly 1% of GDP under its baseline economic scenario and ramping up these measures (alongside additional spending) should a more severe situation unfold.

Elsewhere, Quebec will offer a about $2 billion in liquidity measures to affected businesses, while New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and PEI have pledged business support packages worth 0.3%, 0.3% and 0.4% of GDP, respectively. Alberta and Saskatchewan, meanwhile, will follow through with previously announced tax cuts. While these will be longer-lasting, they’ll certainly deliver some short-term stimulus. Nearly every province (except Saskatchewan) either introduces or beefs up their contingency fund (to a total $14 billion versus about $7 billion in FY 2024/25) to protect their fiscal positions from unexpected weakness or to backfill unanticipated spending pressures.

All told, we estimate that these support measures amount to roughly 1% of GDP across provinces in FY 2025/26, in line with what we had assumed in our latest forecast. This figure doesn’t include federal spending commitments, but with the federal budget landing in the fall, stimulus flowing from Ottawa will likely be a 2026 story.

Bottom Line

With Canada’s economic fortunes upended by the trade war with the U.S., provincial revenues are expected to take a hit this year, lifting provincial deficits and adding to already elevated debt levels. Provinces have taken a defensive stance in light of these risks, introducing measures meant to buffer their respective economies in the short run. However, we’d note the general absence of measures that could “transform” Canada’s industrial base, as has been talked about at the federal level.

Ramped up capital spending plans also feature heavily during this provincial budget season, although they can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, economic growth could be stimulated by infrastructure investment, but on the other, debt burdens will also be upwardly pressured.

Disclaimer

This report is provided by TD Economics. It is for informational and educational purposes only as of the date of writing, and may not be appropriate for other purposes. The views and opinions expressed may change at any time based on market or other conditions and may not come to pass. This material is not intended to be relied upon as investment advice or recommendations, does not constitute a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should not be considered specific legal, investment or tax advice. The report does not provide material information about the business and affairs of TD Bank Group and the members of TD Economics are not spokespersons for TD Bank Group with respect to its business and affairs. The information contained in this report has been drawn from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed to be accurate or complete. This report contains economic analysis and views, including about future economic and financial markets performance. These are based on certain assumptions and other factors, and are subject to inherent risks and uncertainties. The actual outcome may be materially different. The Toronto-Dominion Bank and its affiliates and related entities that comprise the TD Bank Group are not liable for any errors or omissions in the information, analysis or views contained in this report, or for any loss or damage suffered.

Download

Share: